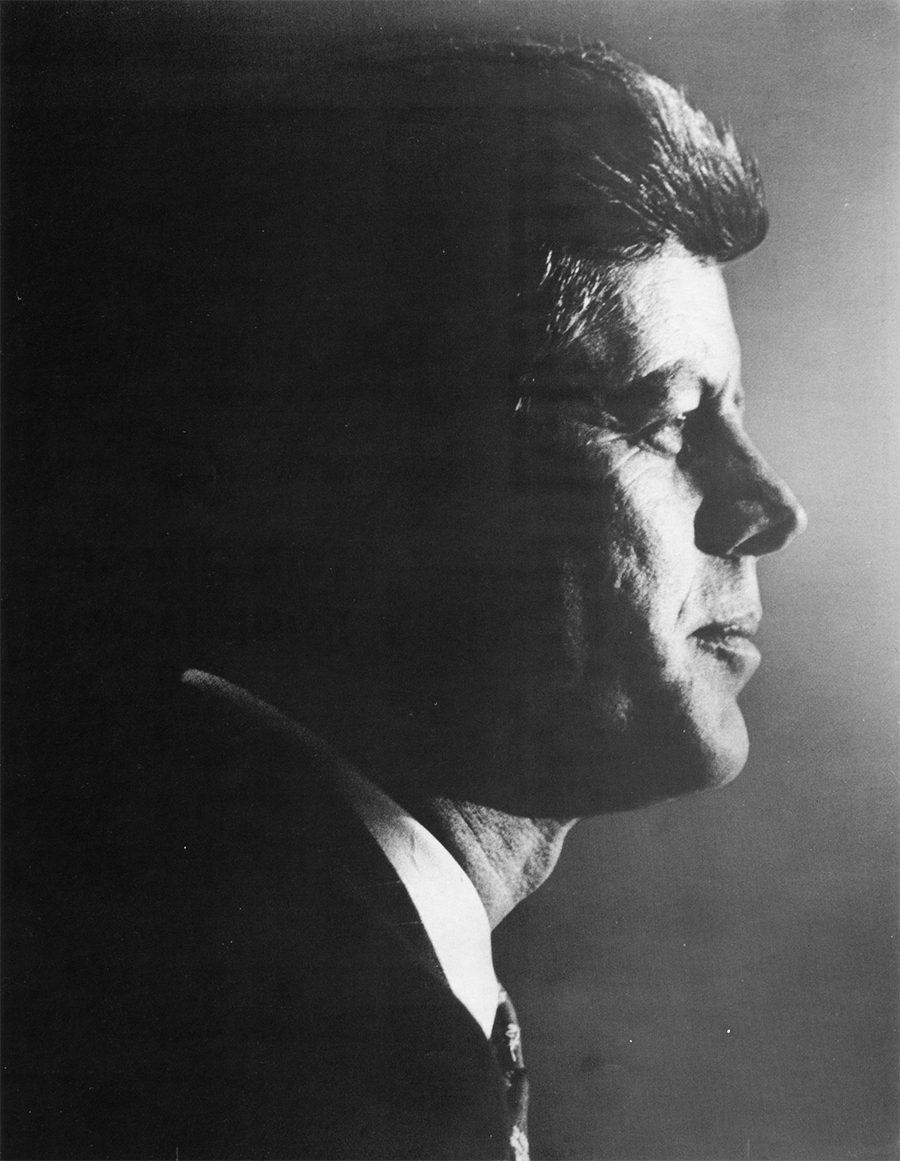

The year was 1960, and a younger senator from Massachusetts had come to West Virginia to show the world that he would be the next president of the United States.

By Rebecca Gatehouse

HQ 1 | AUTUMN 1989

In 1960, John F. Kennedy and Huntington had hit their strides. The young Massachusetts senator and presidential hopeful was riding high from a primary victory in Wisconsin, and Huntington was basking in the height of its industry, commerce and population. The two met that spring when Kennedy swept into West Virginia with an entourage of family members and an organization unmatched to win the presidential primary in a state he said would catapult him to the Democratic nomination.

He had come on a challenge. A challenge to the Democratic Party that he, a Catholic, could win in a state where Catholics comprised only 4.5 percent of the population. The state had been pegged as one that would tighten its Bible belt and squeeze Kennedy out of the race.

However, Kennedy had been promised the support of Gov. Pat Brown of California and Gov. David Lawrence of Pennsylvania and their large number of convention votes if he could win in such an overwhelmingly protestant state. Kennedy told voters, supporters and opponents that if he won West Virginia, he could not be denied his party’s nomination. Here was the showdown for religion as an issue in the presidency. It was the first time, and some speculate the last, that West Virginia would play such an important role in “king making.”

As West Virginia’s largest city, Huntington didn’t go unnoticed by the Kennedy organization. The Hotel Prichard served as campaign headquarters and temporary home for Kennedy’s brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, who oversaw the campaign in Cabell, Wayne and Mingo counties. During the three trips Kennedy made to Huntington during the primary, his entourage included brothers Robert and Ted, sister Eunice Shriver, Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., and friends Ted Sorenson, Larry O’Brien and Ken O’Donnell. The last two are credited with being the engineers of the Kennedy machine whose well-oiled parts churned out a victory in the state that was decidedly Hubert Humphrey territory before the battle lines had even been drawn.

As chairman of the Kennedy volunteer organization in Cabell County, David Fox Jr. was a political novice. So were his co-chairs Bob Myers and Andy Houvouras, all young Huntington businessmen. The county political leaders were solidly Humphrey men and so the Kennedy organization that sprang up was of enthusiastic newcomers, turned on to politics only by John F. Kennedy. At the request of Kennedy’s state chairman Matt Reese, all three men stopped their normal lives and left work for six weeks to devote their time to winning the county for the young senator.

With an organization in place, Kennedy arrived in West Virginia at Charleston Airport Monday, April 11, fresh from the fight in Wisconsin, with his perennial tan and magnetic smile. Fox, Kennedy and a group of supporters piled into an awaiting car and drove from Charleston via Route 60 to Huntington.

Stopping along the road to speak with a farmer and again at Ona to a retired United Fuel Gas Co. employee, Kennedy said in easy and poised tones, ‘Tm.John F. Kennedy. I’m entered in the West Virginia prima1y I’m running for president.”

Later that day the “tousle-haired” senator, as an Advertiser reporter called him, visited 1,000 employees of Conner’s Steel Division of H.K. Porter Co., seeking the labor vote that most were already chalking up for Hubert Humphrey.

There were two main labor forces at the time: steel workers and garment workers. The steel union had come out early for Humphrey because of his labor record, but later leaders of both labor unions became Kennedy devotees.

Fox remembers almost being able to see the change of heart in the faces of voters as they listened to the Bostonian and switched over to his side. “He had the right answers and came across so genuinely,” Fox said. “People felt he meant what he said.”

Across the street from Conner’s Steel, Marshall College held an entirely different world and audience from that of the steel plant, but Kennedy’s charisma sustained him there, too.

An odd rule forbade political candidates from going on campus, so it looked as if the senator would have to forego a visit to Marshall. But as he did all through the primar, he smiled at those who would thwart him and met the students on neutral territory – Third Avenue between the steel company and the campus. Congressman Ken Hechler had called then-Marshall student Bobby Nelson (now Huntington mayor), who arranged for a nock of students to meet Kennedy safely outside the campus boundaries.

Kennedy offered students what they could appreciate most – a youthful figure – as he jumped atop his car and spoke spontaneously to the more than 500 gathered there. “Ken Hechler tells me that Marshall will soon be a university.” If the crowd appreciated that remark, they were even more pleased to hear him say 18-yearolds should have the right to vote, and college students should have two votes instead of one. He would be criticized later by some journalists for his playfully-intended remark, but the students appreciated it. A poll by the student newspaper The Parthenon later found that students liked Kennedy 2-1 over Humphrey.

Later that month, nearly 1,000 people packed the ballroom at the Hotel Prichard to meet the presidential hopeful. Kennedy returned to Huntington accompanied by his wife Jackie who was making her first trip to the city. Earlier that day she had shaken hands with garment workers and attended teas in her honor given by Huntington ladies. As the band struck up “Anchor’s Away,” the set cue for Senator and Mrs. Kennedy’s entrance, Kennedy told Fox that Mrs. Kennedy was not feeling well and they would have to wait for her entrance. Only later was it realized that she was pregnant with John Jr.

As the hub of the Kennedy campaign in Cabell County, the Prichard was the stage for one of the most salient examples of the remarkable JFK memory. As nearly 600 people stood in line to shake Kennedy’s hand, a young woman approached him with her hair in curlers and wrapped in a scarf. She introduced herself, (her name is lost in history, but let us say Betty Smith), apologized for her appearance but told the senator she had just rushed from the beauty parlor because she wanted so desperately to shake his hand. He told her, “You couldn’t have been more charming any other way.” Smith, so enamored, went back to the end of the line and confronted Kennedy again. He looked up to the face behind the hand and said, “Betty Smith, nice to see you again.”

During his last visit to Huntington before the May 10 election, Kennedy took a three-day bus tour through several coal mining communities. It would seem amazing that a man with all the markings of wealth and comfort and bearing an unmistakable Har ard accent could earn the liking of men who ate and breathed coal dust for a living. He did. It was on that trip that a Logan miner said to Kennedy, “They tell me that you never worked a day in your life.”

Kennedy responded, “Yes, I guess you could say that.”

“Well, you haven’t missed a damn thing,” the miner said.

As Kennedy had expected, and even hoped, the reaction to his Catholicism would test him. Literature and rumor concerning the religious issue, originating both nationally and locally, crept into Huntington. A local minister re-published what is now called the “Bogus Oath,” but was then presented as an actual oath taken by members ofThe Knights of Columbus (to kill and destroy “heretical protestants.”) Rumors circulated that the sisters at St. Mary’s hospital were sterilizing protestant boy babies. Fox said his own minister at the First Presbyterian Church in Huntington told his congregation that he was against Kennedy not because he thought the man wouldn’t be a good president, but because he feared that if Kennedy was elected he would popularize Catholicism as Eisenhower had golf.

Kennedy succeeded in West Virginia by turning the tables on those who would use religion against him. While he asked West Virginians to vote on the issues alone, his campaign quietly forced them to vote on just one: whether they would redeem their national image as people who were bigoted and intolerant. So on that election day the people of West Virginia did give Kennedy his crucial win. But Cabell County was one of only five counties that were never in the Kennedy corner. When the votes were counted Kennedy had 8,391 to Humphrey’s 9,524 in Cabell County. His supporters said money, not religion, had defeated him.

Kennedy volunteers received their champion with open arms — arms which they have since closed tightly around the memories of a time 30 years ago which they say was the summit of excitement in their lives.

Co-chairman Bob Myers recalled to Herald-Dispatch reporter Tim Massey in 1983, “We were all enamored with the man and his cause. If he’d have said, ‘We’ll win if you jump of the Sixth Street Bridge,’ we’d have done it. He had tremendous charisma.

“We didn’t know at the time we were touching history. Jack Kennedy was a ticket into politics and we took the ride.”

Fox says he hasn’t been excited about a political candidate since Kennedy. “Those were the greatest two months of my whole life. I have never enjoyed anything more.”

Ken Hechler has a memory, contained in a picture on the wall of Jim’s Steak and Spaghetti House, of himself, Kennedy and Fox eating at.Jim’s as photographer Maurice Kaplan approached them for a picture. As Hechler stood up, Kennedy placed his hand on his arm and said, “Do you think it would hurt your chances for reelection if you stayed in the picture with me?” Hechler happily sat back down. That meal, as many in Huntington and elsewhere, was paid for by someone other than Kennedy. His workers recall that he, one of the richest men in the nation, never carried any cash ..

Kennedy had his own memories of his days in West Virginia, and he kept them carefully filed in the unfathomable depths of his amazing mind, ready for instant recall. After the primary in West Virginia, Hechler met with Kennedy several times as he hosted Marshall students in Washington. Kennedy would always ask them how things were in Cabell County or if they lived near Ritter Park. After he took office, Fox, Houvouras and their wives saw Kennedy in Lexington, Ky., and the new president stopped and said, “Take care of things in Cabell County.” His memory served him well.

When the last signs were taken down from the campaign buses and the Kennedy clan new out, West Virginia had done what Kennedy said it could do: choose the next president of the United States. A city rightfully pleased with itself, Huntington had been wooed by an ardent suitor in.John Kennedy, and he was on his way to the White House. For West Virginia, Cabell County and Huntington, and for the man, it had been a time for greatness.