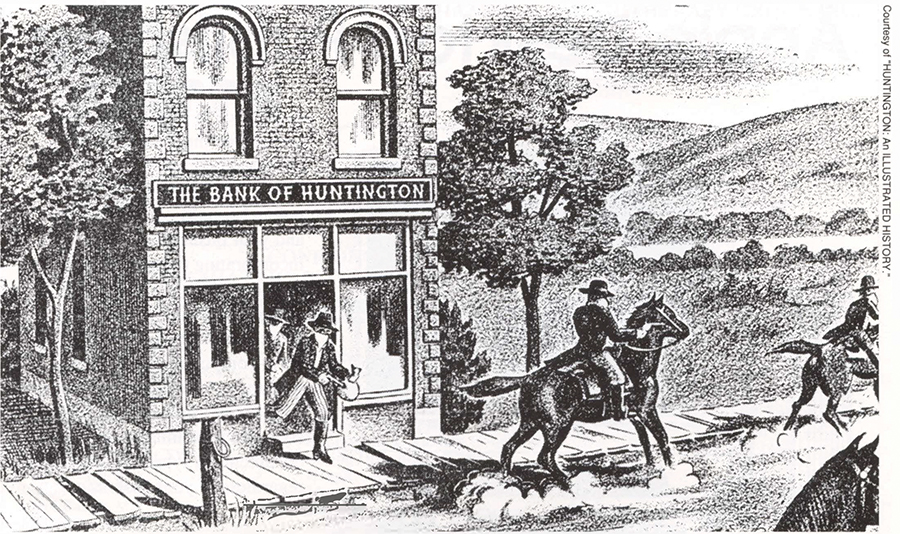

The year was 1875, and four armed bandits reputed to be the notorious James-Younger Gang rode into town, leaving behind a local legacy that is disputed to this day.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 2 | WINTER 1990

After 114 years, speculation continues to flourish about exactly what happened in Huntington on Sept. 6, 1875. The facts surrounding that day have been diluted and embellished with time. Just who were the four men who robbed the Bank of Huntington? Did the group include the famous outlaws Frank and Jesse James and Coleman Younger? The facts may never be known. However, this much is clear: A gang of men rode into town that Monday afternoon and committed the most famous robbery in Huntington’s history.

On Monday, September 6, 1875, an unusually cold day for that time of year, four well-armed men walked into the entrance of the Bank of Huntington. An onlooker later recalled that four top-quality horses pranced nervously at the hitching rail.

Two of the men entered the bank and, in a matter of minutes, the two gunmen who remained outside began firing up and down the street. After the robbery, the foursome spurred their swift horses out of town.

They carried with them almost $20,000 of the bank’s money stuffed into cloth sacks. Although the men didn’t leave their calling cards, later investigation showed that the daring daylight robbery exhibited several characteristics of the JamesYounger Gang, which had been terrorizing the Midwest.

Whenever Coleman “Bud” Younger rode with the James brothers, people referred to them as the James-Younger Gang. According to reports, Younger and Jesse James definitely rubbed each other the wrong way, but Younger stated he and Frank were best of friends.

By 1875 the gang had acquired about ten years experience and had shown that by shooting a teller in cold blood or killing an innocent bystander, they could make bank employees and the public more cooperative for the next robbery.

Assumed to be one of the famous foursome who rode through Huntingon that day, Tom Webb was a small-time outlaw who had moved about in Kentucky and West Virginia for years. Younger met him omewhere in Ohio, possibly in Cincinnati, and introduced him to the James brothers. This meeting resulted in the only incursion into the Mountain State ever made by the James-Younger Gang.

Like all robber gangs, the Missouri boys had unique “trademarks,” such as having top-quality mounts and being heavily armed. Leaving two men outside the bank throughout the robbery while two others took the money at gunpoint was definitely a Missouri outlaw trademark. Cole Younger referred to this system as using “street men and inside men.”

At the time of the Huntington robbery, in the early afternoon, bank president John Hooe Russel had gone to lunch and cashier Robert T. Oney wa alone in the bank.

The original newspaper account reported that two men, with revolvers drawn, entered the bank while two others remained outside. Both of the “inside men “jumped over the counter and secured an ivory-handled Colt revolver lying on the desk. Oney lunged for the pistol, one of two kept on Russel’s desk for just such an emergency, but he wasn’t fast enough.

With four revolvers now drawn on him, the cashier knew he was defenseless. The robbers told him they wanted the bank’s money and if he tried to raise an alarm they would kill him. They coolly ordered him to open the safe. He said it was open, and the robbers replied that they wanted the safe’s inner compartment opened. Oney told them the key was not in the bank, but one of the inside men opened a drawer, found the key, and again ordered Oney to open the inner compartment.

Outside, the other two men, their hands near their guns, kept a close watch on the street. The bank was in an out-of-theway part of town. Few people were about.

Inside, the stubborn cashier still refused to open the inner compartment of the safe. After a few minutes had passed, the robbers tired of waiting and swore they would blow his brains out unless he did as they ordered. This time he complied.

Oney handed out two packages of money, claiming that he had removed all of the cash in the inner compartment. One of the men stooped and aw that the cashier had pushed a package back. They ordered him to hand it to them, as well. The robbers seemed disappointed that there wasn’t more and made Oney show them the previous day’s cash ticket before they were satisfied.

From the newspaper’s account, the gunmen apparently liked the cashier’s spirit. They asked Oney if any of the money was his. He replied that he had about $7 in the bank. Probably to his great surprise, since he had just had his life threatened, they said, “Well, we don’t want this little scrape to cost you anything,” and counted out $7 and gave it to him. They told him that “they had been in the bank-robbing business for some time, and he was the coolest man they had ever come across.” Of course, it must be remembered that the newspaper story of the holdup was based entirely on Oney’s recounting of the event.

In the meantime, a messenger known only as ‘Jim” stumbled on the scene with some papers he had brought from the post office. The gunmen ordered him to stand in the corner and keep quiet, telling him that if he kept quiet he would not get hurt.

They then took Oney and Jim at gunpoint and marched them across the street to where the horses were hitched. Bank president Russel, returning from lunch with a local merchant, saw the men from the corner across from the bank. When Oney noticed that only one of the men was pointing a pistol at him, he yelled. The robbers jumped on their horses and fled.

Russel ran into the bank for his pair of Colt revolvers, but found them gone. He dashed out into the street, shouting the news of the robbery as he ran.

The robbers mounted their horses, fired their pistols into the air, and, within a minute, were riding west down Third Avenue in a cloud of dust. They turned their horses south and rode full speed away from town toward Four Pole, a meandering creek that runs at the foot of the hills south of Huntington.

Russel notified Cabell County Sheriff D.I. Smith who quickly organized a posse and started after the robbers. Arming himself with a double-barreled shotgun, Russel rode out with Sheriff Smith “at breakneck speed up the hills on the other side of Four Pole.” Several Huntington merchants locked their stores, took their horses from the stable, and also set out on the trail of the bandits.

The robbers’ escape route led them up a long and narrow winding road over a steep hill (now McCoy Road, where the Huntington Museum of Art is located) and down to the Wayne County line. They headed for the town of Wayne and then turned west toward the Big Sandy River, the border separating West Virginia and Kentucky.

Soon two posses were riding hard after the four bandits, with George R. Miller leading the second from Barboursville in an attempt to head off the gang. The Huntington posse, led by Sheriff Smith and Russel, got so close that, near the Wayne County line, the outlaws dropped a sack containing $32 in coins and a certificate of deposit for $5000, which were recovered.

In the meantime, telegrams had been sent to all stations between Catlettsburg, Ky., and Louisville as well as to Charleston, Barboursville, and other towns throughout West Virginia.

The members of the Huntington posse followed the robbers to the Big Sandy. Most of this party turned back at the state line, but Russel and four other men went 20 miles into Kentucky and did not return until Tuesday night. Miller’s posse continued the pursuit through eastern Kentucky until the following Monday.

According to The Huntington-Advertiser, the amount taken from the bank was between $19,000 and $20,000, but of that amount less than $10,000 was in currency. The robbery caused no disruption in bank business.

Eventually, Thomas J. Webb was captured in Tennessee with between $4,000 and $5,000 in his possession. He was returned to Huntington for indictment and trial. Another robber, Tom McDaniels, was wounded by two musketwielding Kentucky farmers who were trying to arrest him. He later died from his injuries. Both Webb and McDaniels were identified by Oney as belonging to the holdup party.

Webb was tried in the December 1875 term of the Cabell County Circuit Court, found guilty, and sentenced to 14 years in the West Virginia Penitentiary. Frank James and Cole Younger, alleged leaders of the raid, were never brought to trial for the Huntington robbery. In fact, Frank never served a day in prison for any of his crimes, and later denied knowing anything about the robbery of the Bank of Huntington.

This might have been the end of the story, but famous villains or outlaws, like heroes, take on a new life each time the tale is told and retold. In the imagination of many people who lived in Wayne and Cabell Counties, Frank and Jesse James once traveled the back roads into remote hills. Frank James, especially, has been recalled in stories that have him tending a Wayne County farm and living peaceably with his neighbors under an assumed name as he waited out the law’s pursuit.

One story reports that Frank, under an assumed name, had rented a house in Wayne County and set up a cabinetmaking shop to provide himself with an effective cover and a short-term livelihood. He acquired a local reputation for making good furniture, working hard, and generally behaving himself. But one morning a nearby farmer found that his best horse, a fine bay, was missing from his barn. The following morning the horse was back, tied to a fence rail. The day it had been missing was the day the Huntington bank was robbed. The cabinetmaker also had suspiciously disappeared on that very day.

Folklore of this type has grown like moss around the robbery itself, providing a collection of interesting, yet sometimes conflicting, stories.

In talking with people about the holdup one often hears that the robbers hid out afterwards in a cave in Cabell or Wayne County or in eastern Kentucky. This may be an allusion to the famous cave hideout of the James Gang in Missouri.

Other stories include Jesse James in the four-man party, although there is no evidence he was ever in Huntington.

The histories of Huntington and Cabell County usually include the bank raid, sometimes referred to as the ‘Jesse James Robbery,” as one of the more exciting events of Huntington’s early days.

Colonel George S. Wallace, who was a prominent Huntington attorney and local historian, described the bank robbery and subsequent chase in his 1935 book, Cabell County Annals and Families. Wallace reported that some citizens who saw the four strangers riding into town thought they were preachers, since there was a Methodist Conference in session. These folks commented on what good horses the men were riding.

A knowledgeable source for robbery folklore is Byron T. Morris of Kenova. He is a retired teacher and federal employee who has spent many years studying the history of Wayne County. In his research Morris has become familiar with the lore associated with the bank robbery, much of which centered in Wayne County, since it is believed the robbers entered and exited Huntington through that area.

“One story is that the gang broke up after the robbery to avoid capture,” Morris said. “By this time the report was that the robbers had crossed the Big Sandy River at the Turman Ferry, which operated between the Turman farm in Boyd County, Kentucky and Round Bottom (now Prichard) in Wayne County.

“Another story has it that the four robbers forded the river, two men at different spots, since it was late summer and the river was probably low.

“Frank James left the gang and hid out in a remote part ofWayne County under an assumed name,” Morris continued. “He was said to have been a skilled cabinetmaker and made some beautiful pieces of furniture while in hiding near Cove Gap (a small community near the Lincoln County line). A store owner there is supposed to have acquired several pieces of furniture made by Frank James, including a sideboard, a bed, a dresser, and some chairs.”

In searching through 1930-31 Wayne County newspapers, Morris once found a record of some of the stories that had been circulating in the county up to that time.

A man who lived in Huntington at the time, who claimed to have been a friend of Frank and Jesse James, believed that neither one of them ever lived in Wayne County. However, some of the county’s residents continued to believe that Frank lived there for several years, Morris relates. In the newspapers of the early ’30s that he checked, the events of the midl 870s would have been within the memories of some people still living in Wayne County.

Byron Morris wove the folklore into his own newspaper accounts, in which the story, as people remembered it a halfcentury ago, was told. This particular tale might be called “The Mysterious Man at Cove Gap.”

The story began with the arrival of a man calling himself Frank Morris at remote Cove Gap in upper Wayne County about 1874. He settled down and bought a farm for himself and his wife. Morris was an expert cabinetmaker and built many pieces of furniture during the time he lived in the area. “Nearly all of the pieces were made of black wain u t which seemed to have been in abundance around the area.”

Although Frank Morris soon became highly regarded in the community, there was “an air of mystery” around him and his wife. They were friendly and sociable but they did not discuss their past lives.

Hezekiah Adkins, the Wayne County clerk during this period, later remembered the Cove Gap stranger well. He recalled that Frank Morris was about 5’10” and weighed 160 pounds and that he had dark hair and a sandy beard. He did not think Morris was Frank James since it was thought that James was a smaller man. Others also claimed the stranger did not come close to matching James’ physical description.

Byron Morris found another piece of the story in a 1931 letter to a Fort Gay newspaper from a ”W.H. Peters.” Peters said that his father, DJ. Peters, who lived in Lincoln County near Cove Gap, “had an almost adjoining farm to Frank James’ and saw him often.” The Peters’ knowledge of the alleged Frank James began soon after the Huntington bank robbery when a man and a woman, each on horseback, came past the Peters’ farmhouse and asked for a drink of water.

The man gave his name as Eddie Morris and shortly thereafter bought some land near the Peters’ farm and built a house. The letter writer stated that “the house was built so perculiar (sic) – as you looked at it, you seemed to be impressed by an air of mystery.”

The Peters letter added that “Frank James (Morris) was a kind and friendly man and a good neighbor. He had all kinds of tools and every make of gun barrel.”

Peters concluded by claiming that no one could convince him and many others around Cove Gap that Eddie Morris was not Frank James.

One of the reasons many people thought this stranger was Frank James, the story goes, was that as soon as word reached Wayne County that Jesse James had been killed, he immediately left. He sold out to a neighbor and disappeared as mysteriously as he had come. This neighbor, incidentally, had no doubts as to Morris’ identity and later asked the Wayne County prosecuting attorney for Frank James’ address, so he could forward the balance owed on the farm.

The final proof for many in the area came when the “Morris” house was torn down years later. Amid the debris, a Bible was found. On the flyleaf reportedly was written “Mrs. Frank James.”

Byron Morris cautions that a lot of the residents of Wayne County were convinced of the tale’s veracity. Skeptics may point out that Frank’s local retirement at the very least was short lived, for he definitely was present at the JamesYounger Gang’s disastrous raid on a Northfield, Minn. bank the year after the Huntington robbery. Both brothers retired for a while after that bloody fracas, from which they were lucky to escape alive, but there is no doubt that the two rode together again before Jesse’s assassination in 1882 in Missouri.

Another source for robbery folklore is Wayne County native Doris C. Miller who now lives in west Huntington. Now in her mid-80s, Mrs. Miller is a retired newspaperwoman who worked for The Herald-Dispatch. She is also the author of A Centennial History of Huntington: 1871-1971 . She once wrote a series of articles on the famous robbery for a Wayne County paper, detailing the events as they were known, as well as some of the surrounding folklore. The

“The four men split into two groups coming from Kentucky into Wayne County,” Mrs. Miller said. ”This was their pattern, to split into two parties of two men each. Two of the men crossed into the state at Prichard in Wayne County, riding through a community which used to be called Centerville near where Whites Creek Road divides. After they passed through Centerville, they went over a ridge and down to Lynn Creek near where the creek forked and followed the right fork over to Newcomb Creek and down what is now Newcomb Creek Road at Shoals.”

Miller herself was born at Shoals and knows the lore of the place well.

“The pair went past my grandfather’s house on this same road, stopping at several places to inquire about lodging and old corn for their horses. They were directed to the home of John Backus Bowen and his wife, Hester, which was in Shoals.

“The two men wore black suits, widebrimmed black hats, and the long linen dusters fashionable for horseback riders of the day. They said they were preachers going a distance into Ohio for a meeting.”

On Sunday the men sat out in the yard reading their Bibles. Later in the evening it turned cool and Hester Bowen started to go up the stairs to take extra covers to the guests’ rooms. She opened the door to the stairs and could see up into the room and saw the men were busy cleaning their guns. She told her husband and he came to look, then quietly closed the door.

“It was not unusual for travelers then to carry a firearm for protection, but it was very odd to see preachers carrying guns,” Mrs. Miller explained. “Both Mr. and Mrs. Bowen were past middle age, and they sat up the rest of the night in their room worrying,” but the men departed peacefully the following morning.

This story was told to Doris Miller by the Bowens’ great-granddaughter who died some years ago. “It was thought that one of the two men who stayed at the Bowen home was Jesse James,” said Doris.

Mrs. Miller continued the story with the other two robbers making their way to Huntington. They “crossed into Wayne County at Fort Gay where the Tug Fork and Levisa Fork come together to form the Big Sandy River,” she said. ”The men followed the left branch of Camp Creek and came out south of Huntington. There they rode along what is now McCoy Road across the Wayne-Cabell line and up a long steep hill toward McCoy Road Ridge. In this vicinity there used to be a small community called Hodge named after the family who lived there.

“At the foot of McCoy Ridge, the two men found lodging at the home of James Barbour where they stayed the Saturday and Sunday before the day of the robbery. The story goes that as each man finished a meal at the Barbour home he left a silver half-dollar in the plate. A silver dollar was left on the bed after each man had arisen in the morning. They stayed for two days and nights and left a total of nine dollars which was a nice amount of money for a farm family in those days.” This story was related to Miller some years ago by a grandson of the Barbours.

Mrs. Miller continued that “After the robbery, the bandits fled backoutMcCoy Road. Near Hodge one of them threw a sack of coins close to the Barbour home. Residents of the area picked up the coins, which were returned to the bank.” It might have been that one of the robbers wanted the Barbour family to have a sack of coins.

“Another story has it that as the robbers rode hard out McCoy Road after the robbery, they passed Mr. Barbour who was taking a load of produce to Huntington. He saw that the men had been riding hard and asked how things were in town. One of the men told him it was ‘hot as hell’ in Huntington and rode off.”

The two pairs of bandits retraced their separate routes after they got into Wayne County. “One pair headed back to Prichard and the other to Fort Gay,” Miller said.

Doris Miller’s interest in the famous holdup and in the James gang goes a little deeper than just her knowledge of Wayne County and Huntington history. She said that her family is related to the James brothers. Her great-grandmother, Hannah James Endicott Copley, and Frank and Jesse James’ father were sister and half-brother. The James brothers’ father was a minister who died when the boys were teenagers.

Miller said that her grandfather, Winfield Scott Copley, was reluctant to talk about the relationship in the family, but he told her “at one time, as a young man, he was introduced to two men under certain names, not their own, and later he was informed that these men had been Frank and Jesse James.”

Frank James himself was no help when someone got around to asking him about his West Virginia exploits, for he unexpectedly denied his participation in the holdup. This was on the occasion of his visit to Huntington with a Wild West show in 1.903. He and Younger had teamed up with a Chicago showman to form ”The Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West Show,” which rolled into town on a special 33-car train early on an August Sunday morning.

Memories of earlier crimes had been mellowed by nostalgia, and the newspapers reported that James and Younger walked the streets hindered only by crowds of curious onlookers. Both roamed about freely during the shows, although as a condition of his Minnesota parole Younger was not allowed to take part in the performance.

The subject of the 1875 robbery naturally came up during this visit 28 years later. FrankJames’ response must have satisfied no one. “I was not in the gang that robbed the Bank of Huntington on the fourth (sic) of September, 1875, nor have I ever been in the town before in my life,” he told a reporter forThe Huntington-Advertiser. “I was at my home in St. Joe, Mo. at the time.”

“Not only have I been unjustly accused of robbing the Huntington bank, but many others as well,” Frank went on sanctimoniously. “I am as innocent of complicity in the robbery of the Huntington bank as a little babe.”