By Lee A. Smith

HQ 3 | SPRING 1990

McCoy Road on the South Side of Huntington winds along the hillside, occasionally paralleled by low stone walls, sometimes dotted with bursts of pink spring blooms or lush leaves of summer.

Past the Ritter Park Rose Garden, the road takes many twists and turns, some steep and some unexpected – much like the history of the Huntington Museum of Art to which the road leads.

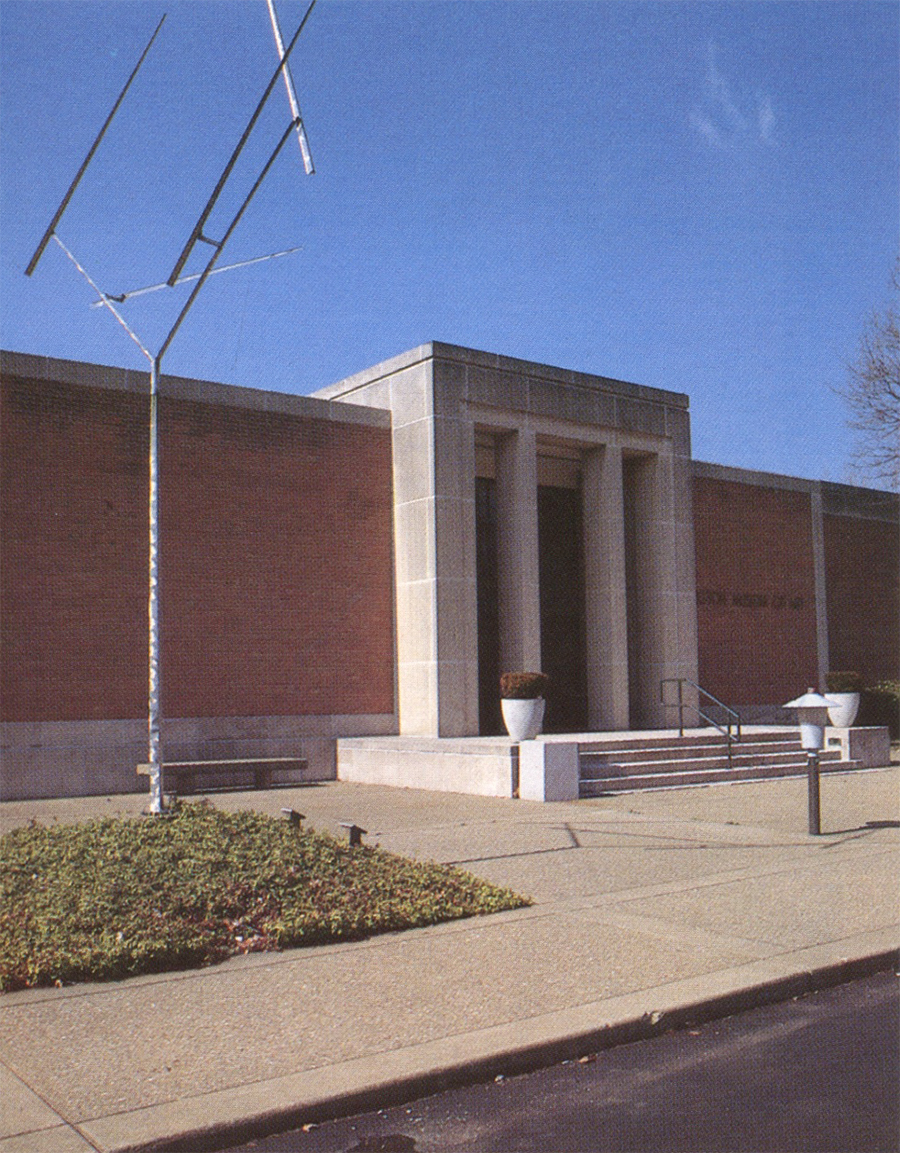

Since its beginning in 1952, what was then called the Huntington Galleries comprised 50 acres and a brand new building. During the following 38 years, the museum flourished: An addition was built, collections grew and arts and science programs tying the museum to the Tri-State community expanded.

Director Tom Butler is tracing the route of the museum by writing its history, much of it based on the letters of local journalist Bill Bellanger. Butler said he also used newspaper clips from as far back as 1947, and he has interviewed people in the community who have been involved with the museum for many years, such as Virginia Van Zandt, trustee emeritus who was on the board during the establishment of the galleries.

Butler said he has pieced together an outline of about 100 pages. “But that just scratches the surface,” he said. “Now I’m going back for details.” Butler said he hopes to be finished with the project in time for the 40th anniversary of the museum in 1992.

The history will cover the bumpy times as well as the smooth. “Since it opened in 1952, it has had its share of ups and downs, successes and setbacks,” Butler said.

For years, Butler said, there was talk about starting a gallery of art in Huntington.

A group of citizens formed Huntington Galleries, Inc. Headed by James A. Francis, president, and Herman P. Dean, vice president, those interested in getting the galleries established debated its nature: Would it be an art academy? A children’s museum? How would studios be used? How would it be linked to then Marshall College and other institutions of learning? Van Zandt, youngest board member and one of only three woman asked to serve, said the group met in The First Huntington National Bank building to plan fund-raising strategies and dream of construction.

The real move toward establishing the galleries came in 1949. Former Huntington Mayor Rufus Switzer specified in his will that two-thirds of the residuary income of his estate be left to the galleries. That amounted to $20,000 per year. The path was cleared for those funds to go to the galleries in April 1949.

The board quickly initiated a fund-raising drive, kicked off by a gathering at the Hotel Frederick, and money raised by that drive exceeded $250,000.

In addition, Herbert Fitzpatrick had donated 50 acres of land on which the galleries was built, plus pieces of art that are part of the permanent collection. Ground was broken Jan. 5, 1950, and by Nov. 9,1952, with a few hundred members, the building was dedicated.

During construction, Van Zandt said, the search was on for a director. By the time the doors opened, Thomas S. Tibbs of Rochester, N.Y., was hired.

“He was a remarkable man,” Van Zandt recalled. “We had nothing, absolutely nothing, and Mr. Tibbs even had to build the display cases which house the silver collection even today.”

In 1957, the galleries received the George Bagby bequest, a collection of English portraits. The galleries board was “surprised but flattered” by Bagby’s gift, Butler said. The donation was unexpected because Bagby was a Grayson, Ky., man with no apparent ties to the Huntington area.

The Ruth Dayton donation in 1967 was the next major gift the galleries received. It included 300 pieces of art and, to date, it’s the museum’s largest single gift.

By 1968, construction had begun on the first major addition, which was designed by architect Walter Gropius. Butler says it was the only museum design Gropius saw finished in his lifetime.

The wing was funded through a $1 million donation by the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Charitable Foundation in New York, Butler said. ‘This addition put the gallery in a class of art institutions far above anything else in our region at the time.”

Roberta Emerson became director in 1972. She was an accomplished business person, according to Butler. She loved the galleries and had definite ideas about its future. Emerson built the budget and, it follows, the staff. Butler said she took the galleries through a time of unprecedented growth, helping to turn the small-town galleries into what now is called one of the finest small museums in the nation.

Emerson hired the current chief curator and glass expert, Eason Eige, who has worked the collection into the finest collection of Ohio Valley glass in the world. She also hired Louise Polan as curator. One of her major tasks was to organize and catalogue the Herman P. Dean Firearm Collection.

Emerson hired the first professional development director to coordinate fund raising,” Butler explained. “The budget really called for this kind of move. It was growing rapidly.”

One of the most famous exhibits in the nation was the Armand Hammer collection which appeared at the galleries in 1982. Emerson said she had attended a meeting of the American Association of Museums and met an official with the collection. She expressed interest in getting it and decided to write to Hammer. In addition, she asked the governor and congressman for a recommendation.

Van Zandt said that at the time, Hammer had purchased Island Creek Coal Co., which had offices in Lexington, Ky., so Hammer was interested in getting to know the area and promoting good relations.

He agreed to loan his collection and he even visited the area when the exhibit opened. Van Zandt said he flew in to Tri-State Airport in his private jet long enough to examine the exhibit and attend a 200-person dinner party that she hosted. “He was so pleased with the installation of his exhibit,” Emerson said. “He said it was the best he’d seen.”

Emerson added that Hammer was impressed by the friendliness of the people in the area and he continues to show interest in and respect for the museum. He donated a collection of lithographs which are still being framed, and recently contributed $10,000.

In 1986 the galleries concluded a $2 million fund drive with a one-of-a-kind success story, Butler said. The National Endowment for the Arts gave the galleries a $250,000 matching grant.

Besides the recent good luck in fund raising, the museum also serendipitously acquired a fine collection of glass. Harrison and Louise Hoffman, a couple from Connecticut, was seeking a home for its collection of 19th century glass, which belonged to Mrs. Hoffman’s mother, Louise Sinkler.

The Hoffmans contacted the National Trust for Museums for suggestions and were given a list of three to try. First, Mrs. Hoffman contacted the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “They weren’t interested,” Butler said. “They never even looked at it.”

Next, she called the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, N.Y., but the curator was literally out to lunch. Third on the list was the Huntington Museum of Art. When the couple spoke with Eige, he immediately knew the kind of treasure they had, and was thrilled to offer the collection a home.

With a membership of 2,000, the museum continues to move ahead. Nationally, Butler said, it can hold its own and has been accredited by national groups. “The museum is seen as a leader in the art world,” he said.

Many people from out of town are exposed to the museum. Michael Cornfeld, chairman of the art department at Marshall University, said when art conferences are conducted at the university, evening activities are scheduled at the museum.

“We want to show it off,” he said. Compared to facilities in other parts of the country, the museum rates high. “It’s a major asset to the community and it does a super job,” Cornfeld said.

The museum has brought Huntington into the move begun in the late 1970s, which recognized that important art can be found outside the major cities, such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington, D.C. That growth was acknowledged, in part, by the name change in 1987 from The Huntington Galleries to The Huntington Museum of Art.

The reason for the success of the museum is easy to explain: It’s alive and interactive with the community.

‘We don’t make it a mausoleum, we make it a museum,” Butler explained.

This spring, the museum is offering adult classes including drawing, pottery, photography, arts and crafts, painting and additional children’s classes.

“Children are very important to us,” Butler explained. “They are growing up being used to going to the museum. We’ re becoming part of their lives at an early age.” Day camps focusing on art, science and nature are available to children.

As the 40th anniversary of the museum approaches, Butler is looking down the road to planning an expansion of as much as 8,000 square feet. The addition would be used to show more of the collections. He said it would be the first discussion of expansion in the last 23 years and he hopes to see some progress in the next three years.

And although gifts to museums are becoming tougher to obtain due to laws making donating less desirable financially, Butler said the museum has some promises of gifts including glass, paintings and prints. Donations, combined with the added space, could put the number of art objects displayed at about 20,000.

“Some of the changes coming up, namely the addition, will be the transition into not being a small museum anymore.”