Marking the 20 Year Anniversary of the Marshall University plane crash, a Huntington writer remembers her neighbors.

By Ginevra Ginn Tidman

HQ 5 | AUTUMN 1990

It was a nightmare no one could have dreamed. Twenty years ago, on the night of November 14, 1970, the air was cold and grey. Visibility was near zero when a chartered DC-9 jetliner

crashed before reaching Tri-State Airport in Kenova. The plane carried 37 members of Marshall University’s football team, 12 staff members, five crew members and 21 alumni and friends. All aboard were killed. The crash leveled an area 200 feet in diameter. The only recognizable objects at the site were the plane’s two jet engines and sections of the wings and fuselage.

Huntington’s Cabell Huntington Hospital, the facility nearest the disaster, sealed off its entrances in gearing up for emergency services that, as it turned out, were never required. In front of the airport a chartered bus, striped in the bright green and white of Marshall’s colors, stood empty and still in the wet night.

The football team had lost a heartbreaking game 17 to 14 to East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, that Saturday afternoon; and all 75 people aboard the plane lost their lives that evening.

My husband and I were watching “Mission Impossible” on television when we first heard the station interruption announcing that a plane had crashed as it approached the airport.

My husband said, “Oh, my God, could it be the one the Heaths are on?”

Elaine and Emmett Heath were our neighbors. Our association with them was through their daughter Kathy – one of their four children. She had been the best friend of our daughter for nine years, ever since the third grade.

The Heaths had lived in Huntington for 12 years. Emmett owned a muffler outlet and was sales representative for a women’s sportswear company. Elaine ran the house and looked after their four children.

She was a small woman, barely 5 feet, 2 inches, if she stretched. Her eyes were green, hair dark, her face vivacious. She was far from looking her 43 years.

Emmett, a man six feet tall, weighing about 200 pounds, was also 43-years-old. He had intense blue eyes and a prodigious sense of humor. His gift of laughter served him well because the Heath home was one of incessant activity with family and friends coming and going at all hours.

Emmett was called “Happy” by his friends. As a matter of fact, the family was known as the “Happy Heaths.”

The Heaths added a spacious room on the back of the house to help contain the family activities. A shingle over the door leading from the outside into this room read “Heath’s Inn.” It might appropriately have read “Heaths In” because someone was always there.

The big brick house swarmed with young people, our own daughter among them. One day I phoned her and Happy answered. “Let me look,” he said, adding, “if she’s not here, she’s the only one who isn’t.”

At the time of the crash, young Jeff Heath was 19 and a student at Marshall University; Kathy Watrous, our daughter’s friend was 18, married, and the mother of little girl just three weeks old; Holly Heath was 15 and in high school; Kevin Heath was just 11 and in elementary school.

On Saturday morning the week before the crash, Elaine came running up our driveway. “Come on over and see my grandbaby,” she said. “I’m taking care of Kathy’s baby, and I want you to see her.” Elaine knew how much we loved Kathy; my daughter and I had given a baby shower for her.

We admired the baby lying in her bassinet, and told 15-year-old Holly what a young-looking aunt she was. While we were there Happy arrived waving two narrow strips of cardboard in his hand. “I got them,” he proclaimed. “I got tickets to the Marshall-East Carolina game.” The Heaths, although not Marshall University graduates, were zealous and indefatigable supporters of their adopted hometown team.

“When do you leave?” my husband asked. “And it’s none of my business, but what’s the price?”

“The plane leaves Huntington Airport at 7 :30 next Friday evening,” Happy told him. ‘That’s Friday the 13th, but we’re not superstitious, are we, Elaine? The tickets are $50 per person – that covers the plane fare, one meal, your lodging and a ticket to the game.”

When we heard the first television announcement of the disaster the following Saturday evening, we knew what had happened. We ran to the front of our home from which we could see the Heath house. One look confirmed our fears. Every light in the house from the basement to attic blazed into the murky night. The house resembled a ship alight, plowing through a dark night ocean. The lights shimmered in the falling rain.

I looked at my husband. “Oh, Bill,” I said. And that was all I could say.

We went back to the television to listen in horror as the news unfolded. I remember lighting two hurricane candles on the window sills in the television room. I don’t know why. To be doing something, I guess. Their flames blurred through the tears in my eyes.

Many stories have evolved from that night. My story is one that has never been told before. It has confirmed for me that while there are tangible needs of the body, there also are mysterious needs of the spirit, which are often met in strange, little-dreamed-of ways.

What to do for these four young folks? My first thought was food, because I knew there would be flowers by the garden full, and young people are always hungry. So I cooked a ham and prepared baked beans in a fat crock. Perhaps they would serve as mute evidence for the feelings I could not express.

Then I remembered. I could give them the gift of words. Somewhere I had read a poem about a husband and wife who had died together. I couldn’t remember the poet’s name, nor the first line of the poem. But I knew the poem contained words the young Heaths should read now.

“What are you hunting?” my husband asked as I rummaged through our books, which were scattered all over the house.

“A poem,” I replied.

It took two trips to the public library before I finally found it in Herbert R. Mayes’ “An Editor’s Treasury, Volume II.” The poem is titled, “An Epitaph upon Husband and Wife, Which Died and Were Buried Together,” and was written by Richard Crashaw, an Englishman who was born about 1613, and died in 1649.

Crashaw was a poet of in tense feeling who delighted in expressing physical experience. I had found this beautiful poem, so appropriate, I thought, for Elaine and Happy. I hurried and sent a copy of it to Kathy to share with her sister and brothers.

“To these, whom death again did wed,

This grave’s the second marriage-bed.

For though the hand of fate could force

‘Twixt soul and body a divorce,

It could not sunder man and wife,

Because they both lived but one life.

Peace, good reader, Do not weep.

Peace, The Lovers Are Asleep.

They, sweet turtles, folded lie

In the last knot love could tie.

And though they lie as they were dead,

Their pillow stone, their sheets of lead

(Pillow hard, the sheets not warm),

Love made the bed; they ‘ll take no harm.

Let them sleep: let them sleep on,

Till this stormy night be gone,

Till the eternal morrow dawn.

Then the curtains will be drawn

And they wake into a light

Whose day shall never die in night.”

The poet writes of “this stormy night,” such a night as the one in which Elaine and Happy died.

And the word “turtles” refers to turtledoves, one definition of which is “Persons who are demonstratively affectionate, beloved persons or sweethearts.” And the Heaths were that.

For many life halts with the enormity of such a plane crash, and they are stunned with their mourning. But there comes a time when the little tasks that consume time are upon us all again.

Time passed. It was another November day, and I had come to see the newly-erected Marshall plane crash memorial and visit the graves of Elaine and Happy.

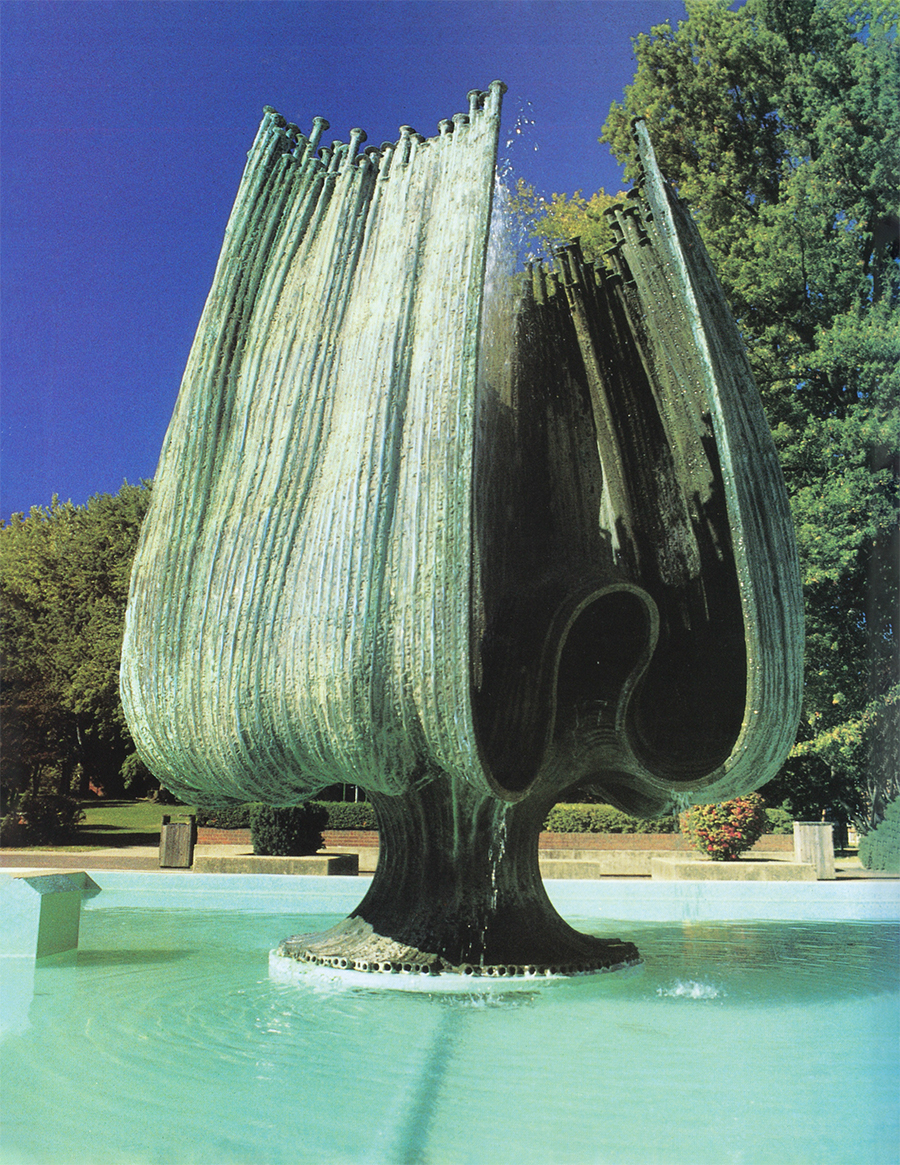

I had not seen their place of burial since the day of the funeral. There are two memorials to the plane crash: one a fountain on the Marshall University campus just outside the student activities building, the other at the cemetery.

The site at the cemetery is incredibly beautiful. It rests, appropriately, atop a plateau overlooking the city. Tall trees make a circle of green around it in the summer lending privacy to grief; in autumn, the circle bums red and gold and russet; in winter, when the trees are bare, you can look out over the plateau and see Twin Towers at Marshall University lifting skyward.

The memorial itself is a slim, gray marble column topped with a simulated flame and, on the front, a wreath symbolizing the esteem in which the citizens of Huntington hold those who lost their lives. The names of the 75 persons aboard the plane are listed on the four sides of the column, and these words are engraved in the marble: ”They shall live on in the hearts of their families and friends forever and this memorial records their loss to the University and to the community.” These same words appear on a bronze plaque at the campus site.

Small evergreens grace the short walkways that fan out from the memorial. The visitor who wishes to remember the passengers on the DC-9 can tarry on stone benches. The beauty of the memorial lies in the simplicity of design and its natural setting.

As I stood alone the only sound I heard was the death rattle of the cold November wind in the few remaining leaves on the hillside trees. I thought to myself that after the enormous explosion of sound at the time of the crash, the only sounds must have been of the wind and the searing hiss of flames biting into the wreckage of the plane and the soft murmur of the rain. No voices of people preparing to leave the plane, trying to joke and be happy after losing a football game, thinking of who would meet the plane tonight, and of their tomorrows which were not to be. All those sounds, lost now, forever. Only the eternal wind and rain, weeping softly for what was gone.

I turned to the Heaths’ graves, a stone’s throw from the memorial. The words chiseled in stone are photographed forever in my mind: Peace, The Lovers Are Asleep.

Words excerpted from the poem I had mailed the young Heaths during those dark November days. I had reached out and touched Elaine and Emmett’s children. Young as they were, I had touched them. No one had told me. I was unprepared to see Crashaw’s words on the base of that tombstone.

His words written in England back in the 1700s, had bridged an ocean and almost four centuries to speak again from the tombstone of a husband and wife on the brow of a hillside in Huntington, W.Va.

Richard Crashaw’s words, as I read them again, had the ring of immortality, as words often do. I hoped they would serve as a requiem for the eight married couples who perished together on that West Virginia hillside.

An Epilogue

Where are the four Heath children 20 years later? In Huntington, all four of them at the time of writing, and not without a taste of life in other places.

Jeff, 39, the oldest, lived in Lexington, Ky., and Charlotte, N.C., but returned to Huntington. He is with CSX in the Coal Development Department. He is married to Sally Wolfe, a Marshall University graduate. Their children are Madison, 9, and Taylor, 4.

Kathy Heath Watrous, 38, is a registered nurse and has completed additional medical courses at Marshall. She lived for a time in Louisville, Ky. She is employed at Cabell Huntington Hospital as maternal transport and prenatal outreach coordinator. Kathy has two daughters, Shannon, 19, and Heather, 18. Shannon is now attending West Virginia University, and Heather plans to study there as well.

Holly Heath Wild, 35, “keeps the fires burning” for her husband, dentist Marc Wild, and their three children, Griffin, 6, Bethany, 4, and Tanner, 3. Holly was with Marc at a friend’s house when word of the crash came over the television. She says, “I immediately thought of 11-year-old Kevin who was at home and hurried there to be with him.” Holly became the bride of Marc on May 17, 1980. Her two brothers gave her away, and there was not a dry eye in the aged Trinity Episcopal Church. The couple lives in the big old Heath home. They, too, lived away from Huntington – in Morgantown – but Marc came home to practice his dentistry.

Kevin, 31, sells insurance in Huntington. He is married to Jill Gibson, a Huntingtonian who is an airline stewardess. They have an 18-month-old daughter, Katie, and are expecting another child in November.

Who says Huntington is not a great town in which to live? Take a lesson from the Heaths, “Orphans of the storm,” who found their haven in Huntington.