By Ginevra Ginn

HQ 6 | WINTER 1991

When Walter G. Reggel, 18, a naturalized American citizen from Germany, and his friend, Robert B. Carson, 26, awakened Jan. 24, 1937, they had no idea what they would soon encounter.

“We should have named my boat ‘The Ark,”‘ Walter told his friend Bob that morning. “We’ve been asked to rescue some people from the flood.”

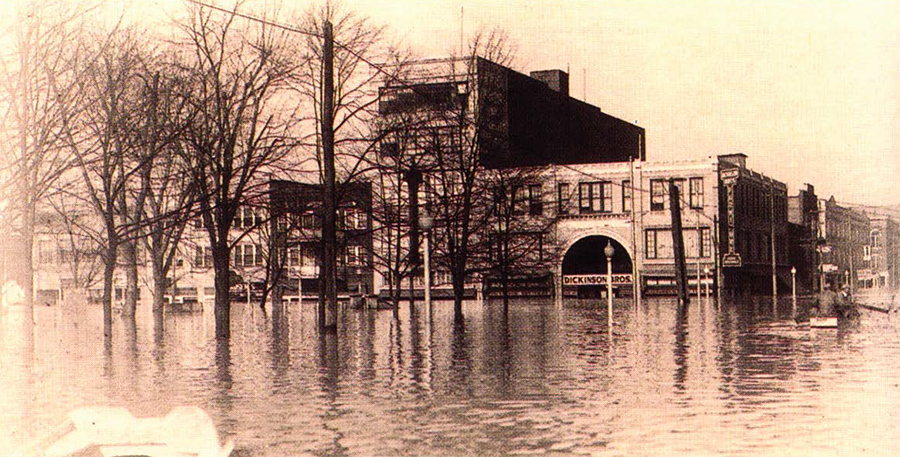

The flood was one of record for Huntington, West Virginia, where the two young men lived. The entire city was paralyzed by the far-reaching waters, which touched 69 feet on the gauge at Lock 28 just below the city. Six thousand people were left homeless.

Experts say the direct cause of the flood was a variation in the normal form of air masses controlling weather over the 304,000 square miles of the Ohio River basin. A series of storm systems crossed the region throughout the month of January, dumping as much as 23 inches of rain on the city. Huntington was almost three-quarters covered by the resulting flood water.

While historically the most serious flooding, it wasn’t the first high waters to hit Huntington.

When the city was 13 years old, Feb.12, 1884, the town was flooded for the first time. A flood in the spring of 1913 forced 2,000 people to find shelter in vacant dry buildings. The April 13, 1913, edition of The Herald-Dispatch reported three babies were born at the refugee center at Oley School. Damage was estimated between $500,000 and $1 million. For many years, this flood was considered the biggest flood of Huntington’s time.

By the end of 1936, residents were preparing for another flood. Heavy rains in December and January 1937 did not foretell the impending crisis. Even newspaper reports indicated the river would crest at 60 feet. By the end of January, however, the river had reached 69 feet – 3 feet above the record.

A flood such as the one of 1937 comes slowly, with water. inching its way into low spots. The thousands of homeless found shelter at relief centers organized in schools and churches. According to Huntington: An Illustrated History, by James E. Casto, 9,000 people per day were fed at such shelters.

Sometimes, people refused to believe the rising danger and did not head for high land in time. Inevitably, lives were lost. Six deaths were attributed to the 1937 flood. This is an account of three of them.

Walter Reggel, a mechanical engineer with what was then known as the International Nickel Co., owned a boat. It was stored at Tinsley’s Sunrise Dairy on Norway Avenue, just west of the Huntington State Hospital. Reggel’s friend Bob Carson, was co-owner of the dairy. The dairy, located high on a hill, was safe from the rising flood waters so Reggel’s boat was dry and ready to be used.

“I hoped I’d catch you at home this Sunday,” Reggel said to Carson. “K.C. Howell, an employee at the dairy, has asked us to rescue a family in the west end of town. Howell’s wife is staying with the family.”

It had finally quit raining. Flood survivors will always remember the interminable rain, sometimes quiet, almost caressing, then at times a downpour of water that resembled a vertical river falling from the sky. And although it was winter, the weather was foggy, warm and dark.

”Will we have room for all the people in the boat?” Bob asked. “I believe so,” Walter replied. “There will be a grandmother, a granddaughter, a mother and Howell’s wife. There will be six of us. I think we can handle that.”

But, Walter’s steel-hull outboard motorboat was crowded. Grandmother Ida Osborne, 60, held her 5-year-old granddaughter, Donna Skyrene Spurlock, on her lap. Little Donna held on tightly to her dog and cat. Donna’s mother Mrs. O.J. (also named Ida after her mother) Spurlock, 28, was aboard as was Mrs. K.C. (Roberta) Howell, 26, whose husband had requested the rescue mission.

Family clothes and prized possessions also were crowded into the boat, and Mrs. Spurlock was carrying a pouch containing $250 – a large sum of money in those days.

“Here’s somebody else who would like a ride,” said Walter, as the little group portaged the boat over a high spot. “Can we get him in?”

Wetzel Adkins, 35, thumbed a fateful ride. There were seven people and two animals in the boat when disaster struck at 10:40 a.m.

The boat was slowly moving its way south on 19th Street West near Adams Avenue. Not far from this spot was a gasoline distributor. All such plants had been warned to make sure their gas tanks were well-secured or to fill them with water so they would not dislodge and float loose, spilling ga oline. But, gasoline had been spilled and about 8,000 gallons were floating on the water.

“We did not smell the gasoline,” Walter later recalled. “I was busy piloting the boat. What happened we don’t know. Perhaps a spark from the motor, perhaps spontaneous combustion; whatever, the gasoline ignited and there was an explosion near the boat.

“Flames rose 20 feet in the air,” Walter recalled. “It was an inferno.”

“There was a loud boom and flames soared high into the air,” Bob said. “We were surrounded by a wall of fire. We all started screaming, and Walter and I yelled for everybody to jump overboard.”

Mrs. Spurlock, Mrs. Howell, Mr. Adkins, Walter and Bob went into the icy water, leaving the grandmother, her granddaughter and two pets in the boat.

Acting Police Sergeant Howard Newman, who was in a boat about half a block away, said he rowed at top

peed for several blocks in a race with the wall of-fire that was bearing down on him.

Bob grabbed Mrs. Howell with one hand and the propeller with the other and went under. “Each time we came up for air we were met by fire, which burned our heads, faces and hands. Five times we went and then came up before the inferno moved on.”

“I had to fight with Mrs. Spurlock,” Walter said. “She was trying frantically to return to the boat to her mother and daughter, but I could see it was already too late.

“When the flames died down, we swam with the women to a nearby garage where we could hold onto the gutters of the roof until rescue came. We had 15 feet of water where the accident occurred.

“I’d say we were in the water 10 minutes before a boat could reach us. It wasn’t easy saving the two women – Bob and I both wore heavy rubber boots and rain coats that day. Luckily, we were both strong swimmers. When help did come, we were all taken to Memorial Hospital where we were given first aid. Bob later developed scarlet fever from his exposure to the contaminated waters.

“The third man in the boat, the hitchhiker, Wetzel Adkins, could not swim. He drowned.”

Three people and two pets were lost in the accident. Two other deaths would later be attributed directly to the flood.

Reggel left the hospital on Feb. 2, seven days after the accident. On Feb. 3, WSAZ Radio conducted a half-hour interview with Reggel. Announcer Bill

Guenther said, “Here we have with us a man, who along with his friend Bob, looked death squarely in the eye.”

Guenther concluded, “Walter Reggel, to you and Bob go the best wishes of WSAZ … If we had a medal to give you two, we would give it.”

Walter and Bob earned no medals, but they did save lives.

• • •

The record high waters of 1913 combined with Huntington’s history of serious flooding helped lead to the construction of a floodwall to protect 17 acres of city against a flood of 73 feet. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed the project in 1943. The new wall was 4 feet higher than the one built in 1937, according to Casto. The Corps calculates that since the wall was completed, it has averted about $175 million in flood damage.

Casto calls the floodwall a symbol of flood protection, as well as a highly effective piece of construction. “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature,” he said in a recent column. “But sometimes you can reason with her a bit.”