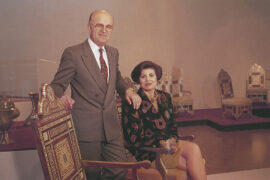

Donnie Robinson, the Kenova Caveman, has earned a major league reputation for enduring pain and pitching the big game.

By Keith Morehouse

HQ 7 | SPRING 1991

It was 5:04 p.m., October 17, 1989. Don Robinson Sr. stood at a concession stand in Candlestick Park, paying for the hot dogs, hamburgers and Cokes he had ordered. As it turned out, he and his wife Priscilla wouldn’t touch the food.

And they wouldn’t see their son, Donnie, pitch in Game Three of the World Series either.

That was the day the World Series stopped; the day of the San Francisco Earthquake.

If you know Don Robinson, you know that it takes a natural disaster or an act of God to keep him off the pitching mound.

“He’s a stabilizer,” San Francisco Manager Roger Craig said. “When things seem to be going their worst, that’s when he wants the ball. He wants to pitch that big game.”

The 34-year-old Kenova, West Virginia native is a modern day “big game” hunter. Ever since he broke into the big leagues, he has stared down many a barrel of a Louisville Slugger, and he wins more often than not. From a 14-6 record and a Sporting News Rookie Pitcher of the Year Award in 1978, to his World Series rings, the honors have come faster than his 90 mile per hour fastball.

It might not have been that way. After the Pittsburgh Pirates 1979 “We Are Family” World Championship, Robby’s right arm began to come apart at the seams.

Indeed, give Don Robinson credit for his 102 Major League wins, but give at least 7 “saves” to Pittsburgh orthopedic surgeon Dr. Jack Failla. He’s performed surgery on Robinson’s right elbow once, his right knee twice, and his right shoulder four times.

“I knew I could stay up here that long,” Robinson said, reflecting on his 13 years of Major League service. “It was just with the injuries I had, I didn’t know if l could come back from them.”

In fact, Robinson’s battered and beaten body has earned him the nickname “Caveman”. Look closely, and those scars on his knee and shoulder do sort of resemble ancient hieroglyphic carvings. Only Dr. Failla knows what they say for sure.

“If you look at his body and you see all the scars, you wonder how he goes out there and still throws as hard as he does,” Giants’ first baseman Will Clark says admiringly. “To do that and to still be as competitive as he is, is pretty amazing.”

Robinson has always thrown hard, hit hard, played hard. “He’s always been bigger than everybody else,” said his father. “And it was always hard to get him to come inside. He was playing ball from daylight to dusk.”

Just like all giant heroes (Paul Bunyan, Hercules and Goliath before him) Robinson can boast of feats of incredible athleticism and legendary strength.

“We had an apple tree in our backyard,” his dad recalled. “I’d gather apples and throw them to him. I’d get down to the core and make him hit it. He’d hit it out of sight. I really believe that some kids can just hit. He could hit.”

If Babe Ruth was a hitter who just happened to pitch, Don Robinson is a pitcher who just happens to hit. Many shortstops in the majors drool over his .241 career batting average, his 13 career home runs, his one grand slam.

“I love to hit,” Robinson said. “I go up to the plate and I guess what the pitcher’s going to throw me, and if he throws it in my zone, I usually hit it pretty hard.”

Hard enough and often enough for him to have won three Silver Slugger Awards as the best hitting pitcher in the National League. No N-L pitcher has won more.

• • •

June 8, 1957, Ashland, Kentucky. Priscilla Robinson makes a perfect delivery of a baby boy and somehow you know Don Robinson was destined to pitch.

“We threw every day,” his dad said. “I didn’t know any better.”

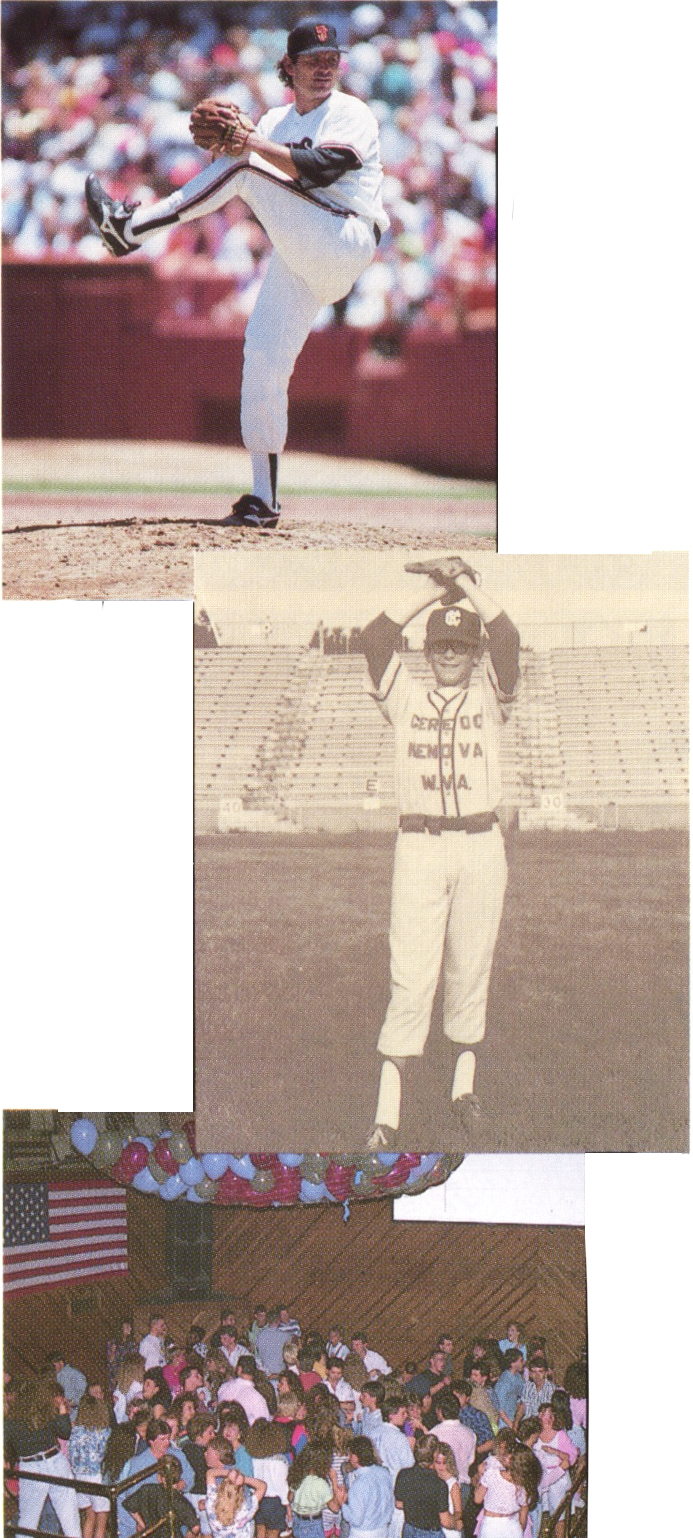

Very soon Don Robinson would develop into a strapping, three-sport star at Ceredo-Kenova High School. He could pitch a football, too, and led the Wonders to the 1975 State Football Championship.

“Going to high school, growing up there, it gave me the desire to do what I’m doing now,” Robinson said.

Even before scars were etched in his right shoulder, his arm had big league written all over it. William “Toby” Holbrook was the coach of the Huntington High baseball team and he tutored Robinson on the summer league all-star circuit.

“He’s the first kid I ever had that I could hear warming up while standing in the bullpen,” Holbrook said. “When a kid throws with that kind of velocity, you know he’s something special.”

Evidently, the Pittsburgh Pirates thought so too. The Bucs took Robinson in the 3rd round of the ’75 draft, and paid him a $31,000 bonus to sign with the club. He’s come a long way since then. He’s in the second year of a two year contract with the Giants that will pay him 1.25 million dollars a year. That’s more money than the whole town of Kenova spends in a year.

“There’s nobody that puts a gun to the owners’ heads and tells ’em they’ve got to pay that money,” Robinson bristled. “As long as they’re giving it out, you want your part of it.”

Robinson has spent a good chunk of that money on a sprawling new home in Bradenton, Fla., where he lives in the off season. But don’t tell Robinson he has forgotten his home. He spent $12,000 to pay off his parents’ home last Christmas. In 1985, he bought them a new Cadillac. And don’t forget the nightclub that bears his name, where many a young man has struck out on a Friday night.

“Since I live in Florida now, I knew I couldn’t help out baseball-wise,” Robinson said, “so I figured I’d help out by starting Robby’s. I thought I’d give something back that way.”

Don Robinson doesn’t spend a whole lot of time in his hometown these days, or in his home in Florida. His wife, Rhonda and two sons, Brad and Brent would like to see more of the man of the house in person, not on television. And even Robinson admits his career is out of its windup and into its stretch.

“Right now, I’d like to pitch two, three, four more years,” he said. “I can keep pitching as long as I don’t get hurt again.”

It’s that junkyard dog tenacity that has kept him in the majors this long. To beat him, Roger Craig says, “means you better battle your butt off.”

“I’ll do whatever it takes to win,” Robinson said. “The main thing when you get up here is to win.”

Robinson is a competitor at all he does. He hits a golf ball as hard as he hits a baseball. You have to when your playing partner is PGA Tour star Paul Azinger.

Maybe the only thing that excites Robinson more than a good baseball game is a good game of cards. His idea of the on-deck circle is a round card table. Pass the deck. Don Robinson will deal.

Coach Holbrook tells a story of a trip his all-star team took to Detroit one year. There was a team of Puerto Ricans in the tournament, none of whom could speak “a lick of English,” Holbrook recalled.

“One night (it was late) and I couldn’t find Donnie, so I checked in another hotel room and he had all these Puerto Rican ballplayers in the room playing blackjack. Donnie had all their money and I made him give it back.”

The Puerto Ricans took plenty of hits that night from Don Robinson.

The next day, Huntington’s team played the All-Stars from New York. They took a hit, too. One. That was all they got from Don Robinson. He won the game 1-0.

To this day, he’ll still pitch on no rest if you need him to – “Whatever it takes to win.”