HQ 7 | SPRING 1991

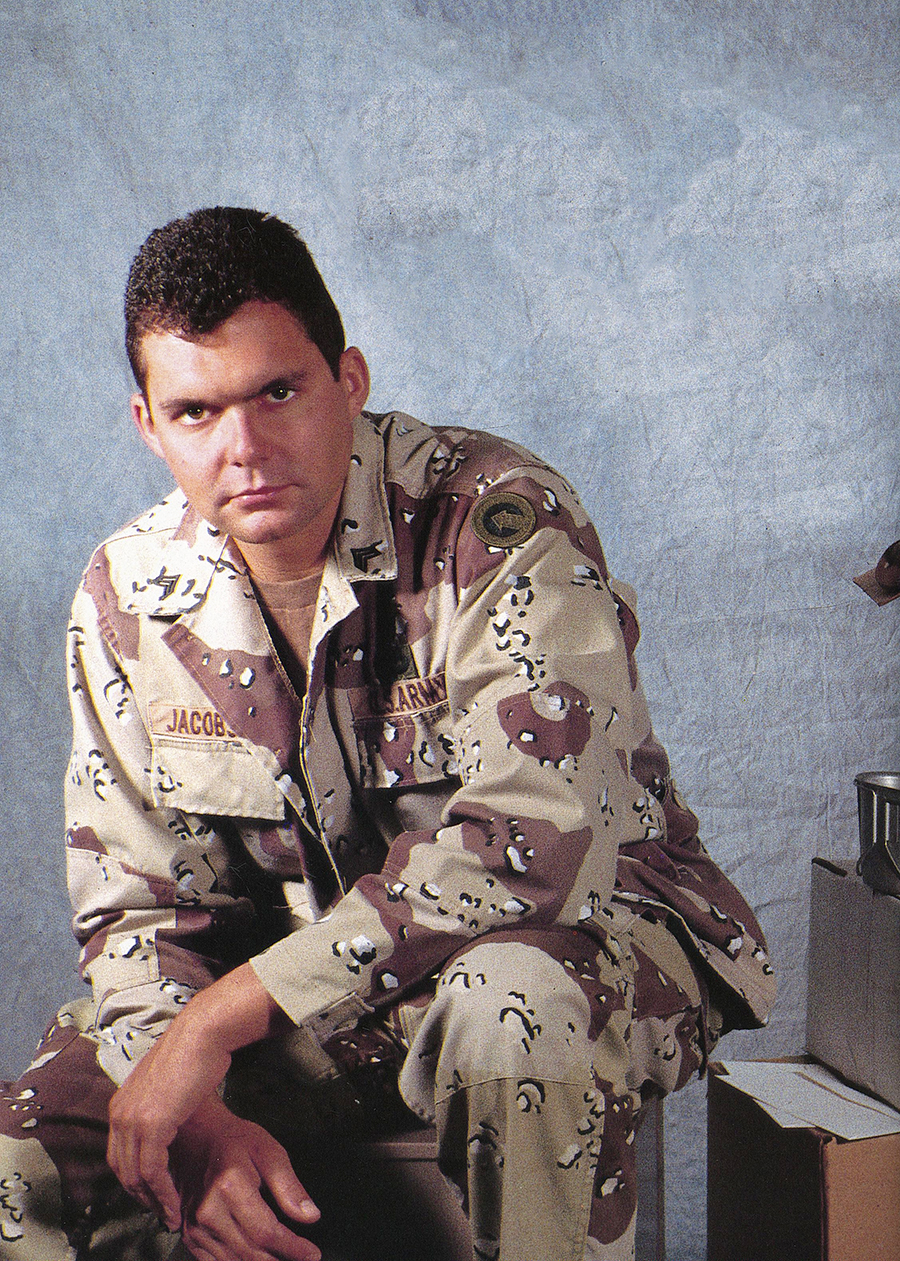

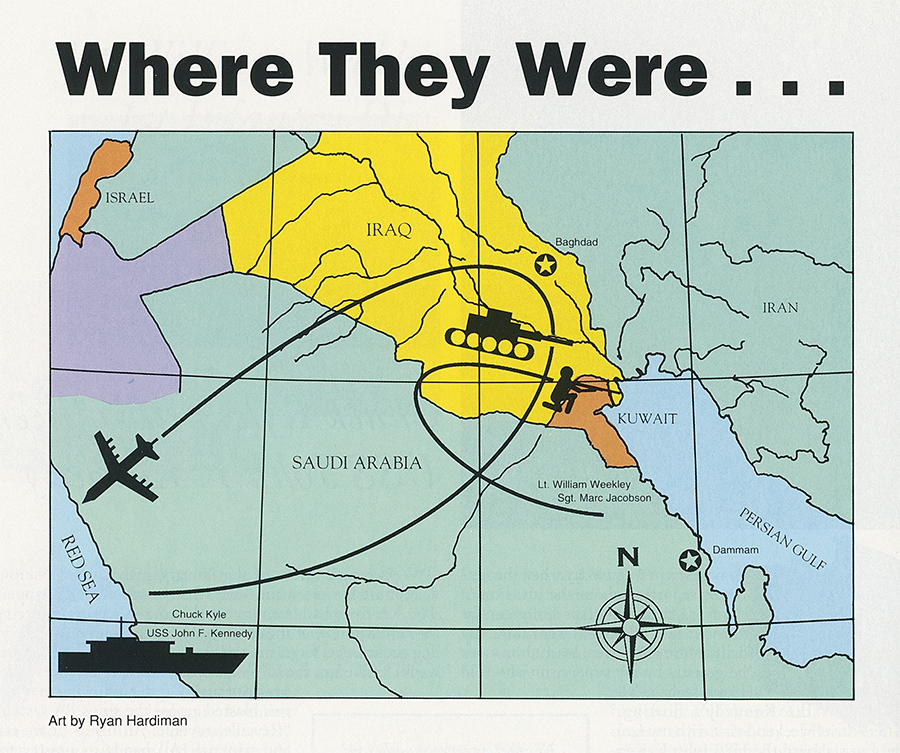

Sgt. Marc Jacobson, 249th Supply Co.

My name is Sgt. Marc Jacobson and I am currently assigned to the 249th Supply Company deployed in Saudi Arabia as part of Operation Desert Storm. I am a chemical operations specialist with the United States Army stationed in Fort Bragg, N.C. My first and foremost priority is the training of army personnel in NBC (Nuclear, Biological, Chemical) defense, or how to survive in a NBC contaminated environment.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, they did so with swiftness. The entire world was in turmoil over what was taking place in the Middle East. Immediately, our company was put on alert status. Before the invasion, NBC defense was not taken that seriously in the army. Suddenly, it was a world issue and I was considered to be the most important person in my company.

I took it all in stride and conducted defense training courses 7 days a week for over a month. We worked on everything from the simplest of tasks such as putting your masks on, to the more advanced tasks such as exchanging protective gear in a contaminated environment. When it came time to deploy, I had little doubt that my company, if it came down to it, could survive a chemical attack. The time to leave had finally arrived and on Sept. 9, 1990, we left for the Middle East with confidence. We flew to Belgium and then on to eastern Saudi Arabia. When the plane was about two hours outside of Saudi, the mood on board changed considerably. Everyone became quiet. I guess we all started thinking about what we were getting into. Maybe everyone was saying a prayer. I know I did. After landing in the desert, the pilot came over the intercom and said, “Welcome to Saudi Arabia. The time is 0630 (in the morning) and it is currently 93 degrees outside.”

I couldn’t believe it. That hot already? Needless to say I was sweating bullets within minutes. We were put into a formation and herded off to Saudi-style tents. The first thing we were given was water and it wasn’t cold. I ended up drinking nine 11/2 liter bottles that day. We were then told to wait. I expected that. After all, that’s what the army is all about – hurry up and wait.

When we finally got our gear off the plane, we had to walkabout a half mile to awaiting buses. Now I have walked a long way before with more on my back than that, but it was already over 100 degrees at 10 in the morning. I nearly passed out. We were driven to a small tent city that was comprised of 10 large Saudi tents. After setting up our areas, we decided to go look for some cold water. Cold water in the summer desert is like the best drink you’ve ever had. It’s great. We finally found a cool water hole and passed the rare commodity out among the troops. At 2 p.m., the temperature climbed to 120 degrees. The women who arrived with us were taken to a different location where they were put up in air-conditioned apartments. We later found out that the apartments were also equipped with a full kitchen, bathroom and washer and dryer. The men went to the bathroom in a makeshift latrine outside with all the flies, scorpions and snakes. We washed our clothes in a bucket. Needless to say, all of the guys in my company felt cheated.

For the first few days, I did nothing but sit and swelter in the heat. I must have lost 10 pounds during the first week. I sweated constantly.

Although it might seem like we had it bad, we really didn’t. We knew we had it better than a lot of people. There were infantry guys living in foxholes in the middle of the desert that had it much worse than us. When I felt like complaining about the conditions, I just kept my mouth shut and did what I was told. I was thankful for what we had.

When I wasn’t training army personnel, I was in charge of driving our company officer to various places in the desert for strategy meetings. I ended up driving all over the country. After a long week of driving duty, I asked the company officer for a few hours off to wash my clothes – I hadn’t changed clothes, including underwear, in over a week. When I was told I could not, I blew up and told the Lieutenant I was taking the morning off to clean up. The Lieutenant informed me that my attitude was not acceptable and if it did not improve, a new driver would be found. Needless to say, the Lieutenant found a new driver the next day.

I received an apology a couple of days later. Apparently the new driver had been getting lost in the desert and I was the only one who knew my way around. I also apologized for losing my cool and was back on driving detail the next day. See what the heat will do to people? We were letting it get to us.

After being “in country” for about a month, headquarters found us a place to set up warehouse operations. Our Company was now in charge of supplying repair parts to the entire theater – everyone in the United States Army.

We had been in the desert for nearly two months and the weather wasn’t getting any better. Men were getting sick almost daily with symptoms that included fever, nausea, cramps and diarrhea. It was usually brought on by drinking out of someone else’s water bottle or eating some of the local food. After three months, I still hadn’t seen a cloud in the sky. And, when President Bush announced that the United States was sending upwards of2 00, 000 more troops to Saudi, we all sighed and lost hope of being here for only a short time.

The month of December was both a good and bad time for me and the rest of the troops in the 249th. The first couple of weeks passed slowly and, with the Christmas Holidays coming up, everyone was thinking of home. But little did we know that our Platoon Sergeant’s sister, Sharon Black, had adopted us for the holidays. Sharon and some of her associates at LRB& W, a large legal firm in Indianapolis, Ind., had decided to take us under their wing. They sent our platoon a number of gifts ranging from socks to walkmans. Everyone was excited to get these presents for the holidays. I have to say that Sharon undertook a tremendous project when she adopted us. She and her co-workers did one hell of a job and we appreciated it from the bottom of our hearts.

We all knew this good cheer couldn’t last and it didn’t. We would soon become accustomed to the word “scud” on a first hand basis. On December 22, Iraq launched its first scud missle attack. It would be the first of many close calls or false alarms we would encounter during our tour of duty.

For the next two weeks, we were required to suit up in our chemical protective gear at all times. After having been in the suits for nearly four days and four nights, we were finally given one afternoon off to clean up. As luck would have it, I was in the latrine with my suit lying on the floor when an alarm warning of a scud missile attack went off. I had a hard time trying to get back into my suit and get out of that latrine. I knew one thing – if I was going to be killed in the line of duty, it wasn’t going to be in a latrine. It wasn’t funny at the time, but looking back on it, I laugh every time I think about it.

The New Year came and went without much fanfare. And, with the United Nations January 15, 1991 deadline fast approaching, our company began to head north. As the deadline drew closer our tension level mounted. We were all hoping for peace but in the back of our minds we knew it would never come.

The 15th came and went and at 5 p.m. on the 16th, our commander informed us that the bombing oflraq would soon begin. We were to spend the night inside metal vans with all our chemical protective clothing. I had set up all of my chemical detection equipment outside and had made sure it was in proper working order. Inside the van we listened to the radio as the bombing ofiraq began. I heard the President tell the world that the liberation of Kuwait was now underway. But, I really wasn’t listening. Instead, I was wondering ifI was going to survive the night. I thought about a lot of things in those hours -family, friends and all the things I had never done. I made a couple of promises to myself that night and I intended to keep them if and when I made it home.

Our Air Force took Saddam totally by surprise. They did so with such force and accuracy that the Iraqis didn’t have a chance to retaliate except with a few scud missiles. And thanks to our patriot air defense system and the men who operate it, a lot of people are alive today, including myself. I will definitely buy one of those guys a beer when I get back to the states.

We moved north again and were now so close to the border that we could see the sky turn red from the bombs and fires. In the distance, you could hear the tremendous explosions. Helicopters and jets flew over our position 24 hours a day. It was an amazing sight to see the B- 52 bombers fly over your head.

At dusk, it was scary and yet, at times, beautiful. Nowhere have I ever been, including Hawaii, have I seen a sunset like I have here. When the sun went down, the stars came out and you could see everything. But it was at night that you also found yourself the most frightened. In the darkness, you never knew if you were going to be attacked.

By now it was February and nothing had changed as far as peace was concerned. We now started to think about the possibilities of a ground war. We were all ready for this thing to be over with. I was coming up on 6 months in country and was getting tired of all the bull. So was everyone else.

On Feb. 22, I was selected to go back south and train on some new East German equipment. As my training got underway on Feb. 23 and 24, so, too, did the ground war. At 7 a.m. on Feb. 2 5, we headed back north to rejoin our company for the invasion of Iraq. At 8 a.m. that same morning, a scud missile landed only one mile from where I had been training, killing 31 people and injuring 100 more. It could have been me. I really feel for those people and their families.

We returned to our position back north on the morning of Feb. 27. By now, the ground war was in full progress with the 82nd airborne jumping into position just outside Kuwait City. Within hours, the marines began the liberation of Kuwait. We were kicking ass. Within days, we had over 40,000 prisoners of war. After five days, Saddam wanted a cease-fire but refused to leave Kuwait without his weapons. On the sixth day, he agreed to pull out and meet all 12 U.N. guidelines for the cease-fire. I twas really over before it started.

I can’t believe it only lasted less than a week. Although I am happy it’s over, I feel sad that American lives were lost. Even though it was only a few, a few was still too many. There are parents, wives, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters who have to live with the fact that their loved ones died needlessly because of one man. Saddam Hussein is crazy and one way or another, he will be stopped. No one really knows why Saddam didn’t use chemical warfare. But I heard rumors that when prisoners of war were interrogated, they said they were afraid of the retaliation they would receive from the United States.

Soon I will be home with my family and all of this will just be a memory. What I have described about my time here in Saudi is accurate. I have to say that this war has changed my ideas about what the army is all about. I really love my life in the service and wouldn’t change it or do it over for anything.

There are a few people I would like to thank for making my life a little easier here. First, Sharon Black, Jackie Murphy and Elaine Brown from LRB&W in Indianapolis. Without your support and letters, it would have been a lot worse.

My little brother Adam. Ace, you helped me a great deal. Just knowing of your accomplishments helped me get through this whole ordeal.

To the NCO’s and enlisted of the 249th Supply Company-We did it!

And finally, to my parents, Edda and Jack Steinberg. You supported me through this whole mess with your love. For that I will be eternally grateful.

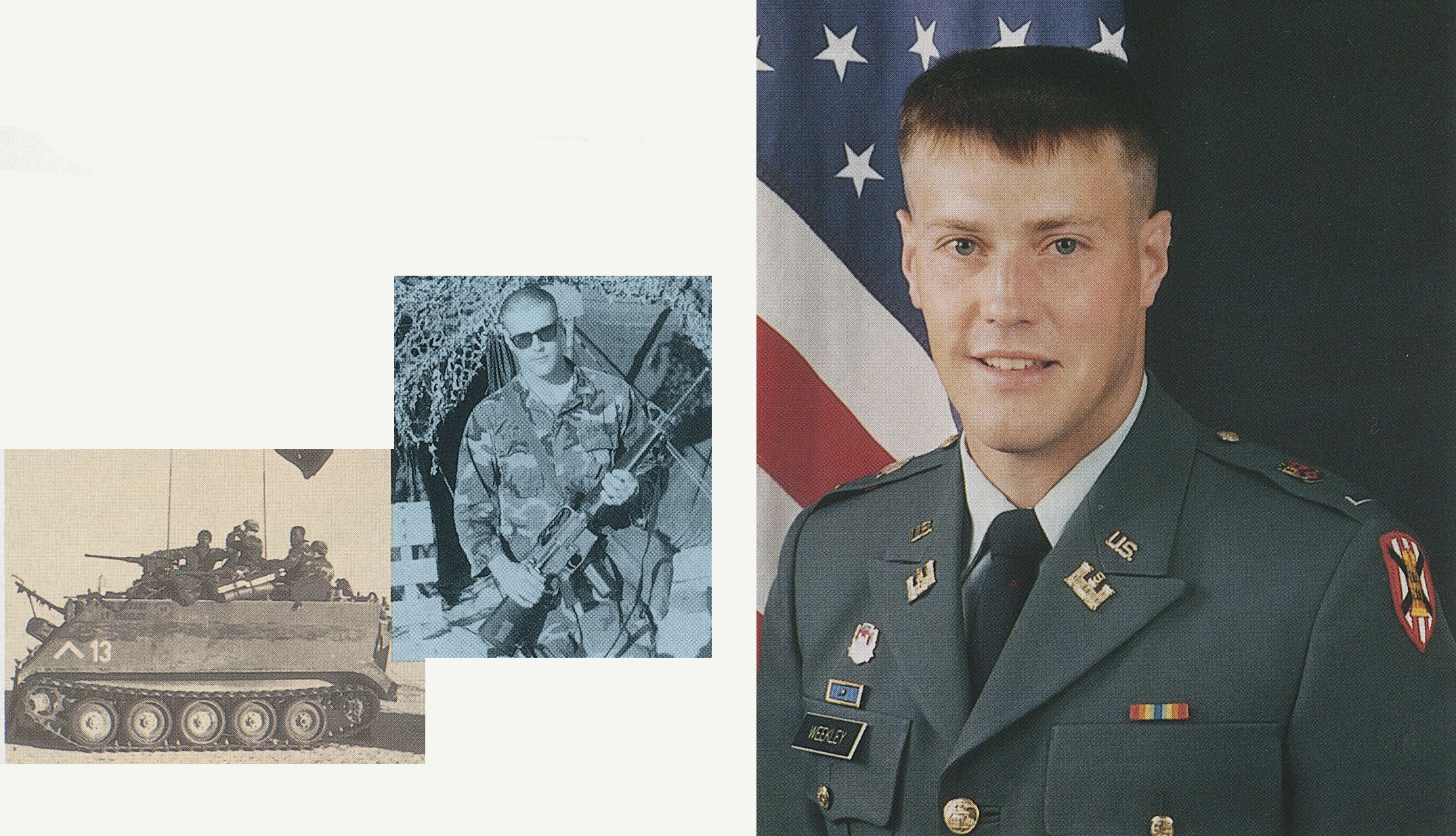

Lt. William Weekley 1st Infantry Div.

For me, it all began on November 9, 1990 when the President announced that more units would be needed to effectively drive Saddam’s regime out of Kuwait. My battalion, VII Corps, consisting of very mobile and high-tech equipped Armor and Mechanized Infantry Divisions was alerted to begin movement from Germany to Saudi Arabia. Only weeks before, we were told that we would be moving from Aschaffenburg, on the Maine River, to Nuremburg, Hitler’s “Capitol of the World.” Our orders to move to this lovely city were put on hold and we immediately began working 18-hour shifts. Within three weeks, our equipment and personnel were ready to go. Left behind was my wife of 14 days. After her graduation, my college sweetheart, Sharon, had joined me in Germany and we began the arduous process of satisfying all the administrative requirements of a German wedding. This culminated with a brief civil ceremony at the Aschaffenburg Rathaus (city hall) the day after Thanksgiving. The battalion officers were all busy loading equipment, so the spectacle of a military wedding was out of the question. My new bride was now alone as I went off to war.

We made a brief stop in Italy and then touched down in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. At first we were not very climatized because we had come from a cold and beautiful Germany to the desolation of the hot desert. Shortly after landing, all the beer we had swilled in Germany the weeks prior to leaving began to sweat out of our pores. We were taken, by bus, to Dammam, a very large port on the Gulf. Here, the weather was beautiful, with daytime highs in the 80s. We lived in giant warehouses on one of the largest docks in the world. The pier was about three miles long and 300 yards wide.

The Saudis took really good care of us. They gave us Cokes and fed us much better food than any mess hall could dream of making. I got a chance to visit the city of Dammam. It was rare to see women outside. I saw a few wearing black robes with two little eye slits. I also found out what happened to all of those classic American gas guzzlers – large Cadillacs, Newports and Impalas. They must have a law here prohibiting cars that get more than 10 miles per gallon. Gasoline cost a whopping 18 cents per gallon!

We were in awe of the amount of tanks, artillery pieces and other weapons systems being unloaded there. One veteran transportation soldier who had served a tour in Vietnam told me that they had unloaded more fire-power in one month than in the entire Vietnam War. I knew at this point that we weren’t there for a show of force but to hit them hard and knock them out quick. I saw enough ammo there that you could probably stack it 30 feet high covering Ritter Park. While waiting for our equipment to arrive by ship, we did a lot of individual tasks training: weapons training, bayonet drill, and chemical training. We figured that when the fighting started we could be fighting as infantry since there aren’t many engineer tasks in desert warfare. After two weeks of the Saudi sun and plenty of hand to hand combat training, we were ready to get out of the “clerk and jerk” environment and start living in the desert.

My unit, part of the 7th Engineer Brigade, was the first to be sent to our part of the desert, just days before Christmas. Our initial mission was to build the Main Supply Routes into the area just south and west of Kuwait.

There was no snow in the desert for Christmas. There was also no water for the showers we’d built. Every day I’d sweat and go to sleep wet and wake up feeling and smelling like my skin was rotting. The battalion wives sent us a VCR tape of them for Christmas, but we didn’t have access to a VCR or a TV, so we listened to Baghdad Betty making fun of us.

We had some alcohol-free beer during guard duty New Years Eve and listened to a squadron of B-52’s bombing the desert. New Years Day it rained for about 3 hours. The rain got all the critters crawling around. Scorpions and snakes were popping up everywhere. By now we had received our initial ammunition load and were ready to start staging for war.

After spending Christmas and New Years in the desert, we were ready to give Saddam his present. At this point, the 7th Engineer Brigade broke down into its component battalions which were tasked out to the various Divisions of VII Corps. After several moves and the politics that occur in the “echelons beyond reality”, we were attached to the “Big Red One”, the First Infantry Division, which suited me fine. If we were going into combat, I wanted to go with the best.

In mid-January it rained an unusual amount and got really muddy! The sand isn’t what you would find at a beach in the U.S .. It is actually very rich, sandy soil with quite a bit of silty clay in it. It appears richer than many West Virginia soils. They just don’t get enough rain to grow anything. If they could irrigate this place, which is possible but very expensive, they could have a Garden of Eden.

Then the Air War started. One reason why the Air Force was so effective, instantly, was because the 5th Special Forces snuck through the border and blew up a lot of lraqi radar, allowing the Air to go in undetected.

By early February it was becoming really noisy. The Marines, over to the east, were getting into it hot and heavy. It’s hard to get any sleep with all the noise. It’s hard to control your imagination whenever you hear an explosion. I kept looking for a horde of lraqis to rush our position. Listening to music on my Walkman helped me keep my sanity. Getting letters and packages from home helped too.

We heard that Saddam had finally figured out that he’d better try to use his Army or completely lose it. That was good. We were starting to get kind of anxious. We learned some useful Arabic phrases: “I am an American soldier; lay down your weapon, or die; put your hands up; come here.”

When all the Corps’ units were finally here, we were tasked out further by breaking the 9th Engineer Battalion down into companies that would support task forces, combat battalions made up of armor and infantry companies, a mortar platoon, a cavalry scout platoon and a company of combat engineers. My company, Charlie Company, 9th Engineers, was attached to 1-3 4 Armor which was designated as the lead battalion for the western assault.

We rehearsed our movements and tactics over and over . We all knew that we were going to try to outflank the Iraqis. Their divisions on the front were basically immobile, undisciplined Infantry Divisions that were placed in a die in-place mission.

The tactics were pretty simple. An Infantry Battalion and Armor Battalion would burst through the Iraqi front line obstacles, then my battalion, 1-34 Armor, would lead the division assault, and the VII Corps assault.

The Iraqis kept trying to hit us with their artillery, but they couldn’t quite figure out where we were because we kept moving around so much.

Quite a few Iraqis walked across the obstacles and just surrendered. They smelled even worse than we did. It reminded me of the way Grandad’s Blue Tick Hounds used to smell. When the Colonel came out to see us, he couldn’t understand why we didn’t “do personal hygiene”. If we had been living in some sheik’s house with showers, we would have been clean too, and nice smelling. But when all you have is a little drinking water, you just have to stink.

We were all hoping really hard that Saddam would pull his troops out of Kuwait. It didn’t happen. But we were now committed to freeing Kuwait regardless of the cost. We were expecting heavy casualties.

At 0700, Sunday, Feb. 24, all hell broke loose. “G-Day” had finally arrived, and we kicked ass. Division began to artillery prep the minefields and the initial enemy fighting positions along a 1,000 meter front with 6 battalions of 8″ self propelled howitzers and 2 battalions of multi-launch rocket systems. It was an awesome display of pure fire-power. After 2 hours of relentless shelling, our lead battalions made the breach of the barrier.

The tanks made the breach using plows and magnetic fields created by wrapping 600′ of 6 gauge wire around a 3 00 pound core and connecting this into the tanks’ 5 0 amp electrical system. This produced a strong enough field that it set off the French magnetic mines ahead qf the tanks. The plows pushed out the pressure sensitive mines. Then we made lanes at 500′ intervals. It only took about 30 minutes to breach. Our battalion then went through the breach.

1-3 4 Armor immediately pulled out in front and led the assault. The Iraqis • didn’t know what hit them. They had been expecting us to attack through the wadis 50 miles to the east and were caught totally by surprise. Our battalion was killing tanks and enemy infantry at will.

Our goal was to attack through 30 km the first day and stop for the night. However, we immediately took thousands of POW’s. They had no idea that the “Americans” were attacking. The Iraqis had never seen that much firepower before. It was absolutely devastating. In the first hour we killed or captured thousands and we only took one casualty in the whole division. My company took 139 POW’s. White flags were waving everywhere. We also captured a Brigade Commander and the 48th Iraq Infantry Division command post, where we found overlays of their Corps plan.

Our prisoners were scared to death of the American Army. It was almost like they were bullies beating up a little kid and all of a sudden a bunch of Mike Tysons showed up. They were totally in awe of our Army.

After sending the POW’s to the rear, we kept heading north, much farther than we had initially planned for the first day. That night my battalion began to engage tanks from the Republican Guard units. Our Ml Abrams tanks were awesome. I saw an Iraqi T-5 5 tank shoot one of our Ml tanks and it was completely engulfed in flames. When the flash died down, there wasn’t a scratch on the Ml. It was almost like it came back to life. It fired a 120 mm “Sabot” round (depleted uranium). It was dark so I could see a red tracer through the night. When it hit thatT-55, it blew the turret off and I saw the back doors come off. Then several other Ml ‘s shot it.

I saw our tanks killing T-7 2 ‘s at over I 1/2 miles in range. The tankers brag that they can hit a 3’ circle at 1 2/3 miles and from what I saw, I believe them. Iraqi tanks were dug in with only the turret vulnerable, and yet they were hit almost every time. The new models are basically 74 ton F-16’s with treads. The best the opposition had was T-72 tanks with a maximum effective range of 1500 meters. These are mid-70s Soviet state-of-the-art.

By the end of the third day we started pushing south into Kuwait where we proceeded fo systematically destroy the 12th Iraqi Tank Division. We did this and did it well for about a day, then they told us to stop. I believe we could have easily taken Baghdad.

At this point, between the Marines, the 18th Airborne Corps, and VII Corps, we had them surrounded. Iraqi officers that were captured said they were prepared to fight several more weeks in northern Kuwait, but when they observed a Corps of tanks and personnel carriers coming from the north, they freaked out. We had them in a I 00 mile circle-shaped kill zone and they were not about to try and fight their way out of it.

When the shooting stopped, we were north of the burning Kuwaiti oil fields. To our south were hundreds of 150′ torches left by the Iraqis. The sky was black and full of smoke. I still needed a bath.

Our Task Force accounted for over I 000 enemy KIA versus 2 friendly KIA. That must be one of the highest kill ratios in history. General Schwartzkopf said that our battalion moved faster and harder (with more combat fire power) than any battalion in history. We moved through 80 miles of dug in infantry in one day.

The A-10 “Wart Hogs” did a pretty good job of shooting up the Iraqi tanks. But Air Power didn’t win the war alone. We killed 3 times as much in a 4 day period of time as the Air Forces did in 3 5 days, and we got them out of Kuwait. But that 3 5 day air prep destroyed their morale and communications. During the attack, a lot of their division commanders couldn’t even talk to their brigade commanders. Corps commanders had absolutely no control. We just left them enough to guard old Saddam from his own people. After the cease-fire, combat engineers were given missions to destroy enemy equipment. My platoon destroyed tanks, bunkers, jeeps, guns and ammo at an astonishing rate. We spent most of one day helping clear the main highway that goes into Kuwait.

The 1st Infantry Division is still (as of 2 5 March 1991) in northern Kuwait and southern Iraqi occupying ground and destroying enemy equipment. But we’re running out of things to destroy. As soon as the cease-fire is permanent, we expect to move south to Sau<li soil again and prepare for our return to Germany. The main body of the “Big Red One” will return to Ft. Riley, Kansas.

Our battalion will receive many awards for its efforts. Two guys will probably get a Silver Star. Several, including me, have been nominated for a Bronze Star. Charlie Company will receive two Presidential Unit Citations to go with the two previously awarded for the unit’s actions in the capture of the Remagen Bridge in WWII.

Chuck Kyle, petty officer USS John F. Kennedy

It was a typical warm August day when the networks began reporting about the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq. At the time, it seemed too far away for me to worry about, so I went a bout my normal daily routine. At 3 p.m. I went into work only to be greeted by my supervisor who told me, “Pack your seabag Kyle, the Kennedy’s floating.” After a brief weekend visit with my family, I was aboard the USS John F. Kennedy en route to the Middle East.

Normally, prior to a six month cruise, an aircraft carrier goes through months of preparation. But by the beginning of September, the crew was completely aware; we were hazy gray and underway, not knowing when we would return.

Everyday the crew prepared for the time that most hoped would never come, war. Continuously, we fought simulated fires, chemical attacks, minefields, and any other accidents that could happen on the world’s largest conventionally powered aircraft carrier. Hours upon end we paraded around the ship carrying gas masks and chemical suits, praying to God we would never have to use them. Even though you can never be too prepared, we had met our limits. Everything was routine. My speciality in the Navy is aviation electronics. I operate a massive test bench that automatically tests electronic assemblies in some of the Navy’s most sophisticated aircraft. I am one member of several teams of technicians that come from Jacksonville, Fla. and Oceana, Va., to work on the Navy’s A7’s, Fl4’s, and S3B’s.

We were all aware of the January 15th United Nations deadline but were wondering what would actually happen. The Kennedy had been involved in many actions enforcing the resolutions, but these too had become routine, an everyday occurrence. Even though we knew there was still several weeks left before the UN’s deadline, one morning we all got a taste of reality as the following message was blasted across the ships PA system:

“Reveille, reveille! All hands heave out and trice up. All hands to muster for quarters and inspection in accordance with the plan of the day. Merry Christmas!!!”

Could it be true? Only in the hearts of the crew was it Christmas Day. For the United States Navy, it was only the 25th of December. It marked the 13 5th day since the crew left their families and friends at the pier back in Norkfolk, Va., and the 30th day at sea without seeing land. For half of the crew, it marked the beginning of the day.For the rest, Christmas was over and it was time to go to bed. Within the hour, jets began launching from the massive floating airport, weapons elevators brought rockets and missiles from the belly of the ship and the rest of the crew went on with their daily activities.

The week went on smoothly until we got news that some of our friends and shipmates from the USS Saratoga had been killed in a tragic accident in Israel. Most of us knew one or two of the casualties.

A new year had begun and everyone just waited. We were completely prepared, ready to go to war if called upon by the Commander in Chief. Shortly after the UN deadline, the Commander of the Red Sea Forces, RAdm. Riley D. Mixson, made the following announcement: “You have trained hard. You are ready. Now let’s execute. For the aircrews, we are all very, very proud of you. I wish you good hunting and Godspeed. God bless us all.”. Once evening fell, under the cover of night, we launched our initial air strike.

Within 45 minutes, 32 planes were airborne, en route to Baghdad. The crew wondered how many of our planes would return. Some speculated we would lose almost half, but no one would have dared bet that all 3 2 would return as they did that next morning. One of the pilots returned from his flight and described Baghdad: “Imagine the Disney World light show, then magnify it 100 times – that’s what it looked like from the sky last night. It was incredible.”

The planes launched every day in different waves attacking different targets. This continued for six full weeks. Fortunately, from the Kennedy, every plane that took off landed back on board by the book, except one.

About mid-January, one of the A7’s, while taking off, damaged its front landing gear. It circled the ship and dumped most of its weapons in the sea and awaited orders from the ship. The crew of the Kennedy placed a large barricade, made of nylon straps, across the landing zone of the aircraft carrier. Everyone was worried. The pilot was going to attempt to crash land his airplane into the net at over 200 miles per hour with live ordnance under his wings. The pilot guided his aircraft down on to the flight deck and slammed it into the barricade. The aircraft was totally destroyed, but the pilot walked away unharmed.

After six months of being at sea, six weeks after the initial air strike, 80 hours after the ground war, and nearly 4 million pounds of ordnance dropped from the Kennedy’s aircraft, everyone sat in front of the TV to listen to the President address the nation. There were speculations of what the President was going to say, but no one knew for sure. Then came a speaker. “Ladies and Gentlemen, the President of the United States.”

“Kuwait is liberated,” he said. Watery eyes looked around toward each other, chill bumps crawled up arms. My God, it’s over.

As I look back on the past 198 days, several things go through my mind. The relief of knowing someday soon we will be coming home helps the days go by. I often wondered if this would escalate to the point that even my 18-year-old brother would be drafted and sent over here. Some days, since our targets were so far from home, I wondered if us being here was going to make any difference. Now I know it did. Even though, deep down inside, I know that I am directly responsible for the deaths of many of God’s creations, I can justify it. We were right, we are Americans. We are free and now, so are the people of Kuwait.

“Sadaam: After six months away from my wife and child, it’s personal.”

This was painted on the side of one of the bombs that was dropped on Baghdad.

For the last seven months and probably the. next month, I have given up my freedom. But I am proud of the way Americans have supported us through cards, gifts, letters, and especially their actions at home. We will be coming home soon to once again enjoy the life that America stands for. God bless you all.

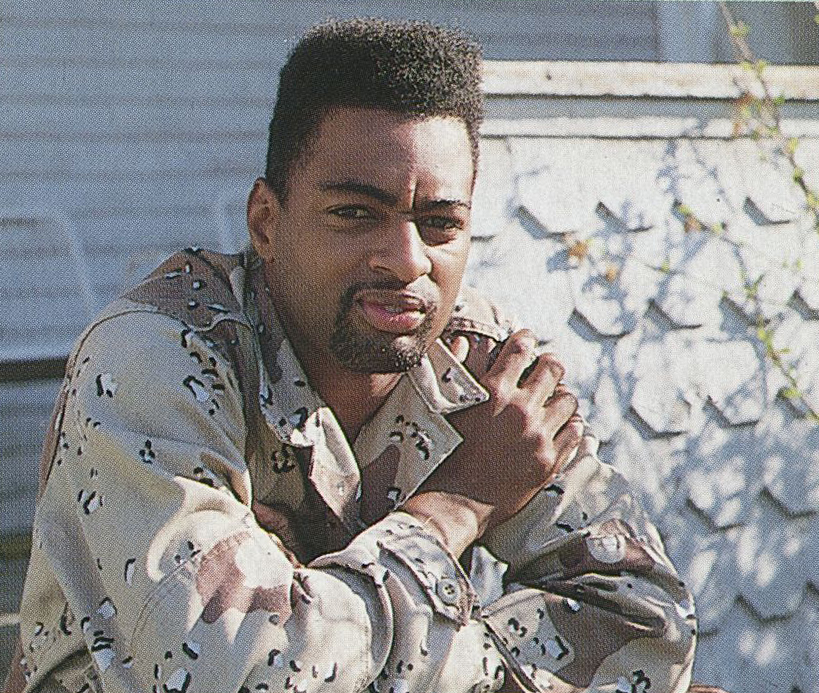

From Fairfield West to the Middle East Communications Specialist Roger Page

It’s a long way from Huntington’s Fairfield West to the Middle East, but Communications Specialist Roger Page has made the journey. The former track standout from Huntington High School graduated in 1982 and then spent a year deciding what he wanted wanted to do. “I really wasn’t going anywhere with my life, so I went down to the army recruiter and signed up.”

It’s been eight years now for the young man from 1801 Ninth Avenue. Page, whose company is stationed out of Savanah, GA, left for the Middle East in August. Like most Gl’s, he was welcomed to Saudi Arabia by temperatures in excess of 120 degrees.

Page was in charge of communications between army personnel and the 24th Aviation Brigade. His six month tour of duty involved the allied forces’s invasion of Iraq.

“Along the way, I saw a lot of blown up equipment, tanks … and a lot of dead Iraqi soldiers. A lot of them looked like they didn’t know what hit them.

“When I joined up, I didn’t think there would be any more wars. The next thing you know, I’m over there. But, it’s been good for me.”