Environmentalists, historians, and hunters all differ on what to do with this treasured area

By Michael A. Friel

HQ 12 | SUMMER/AUTUMN 1992

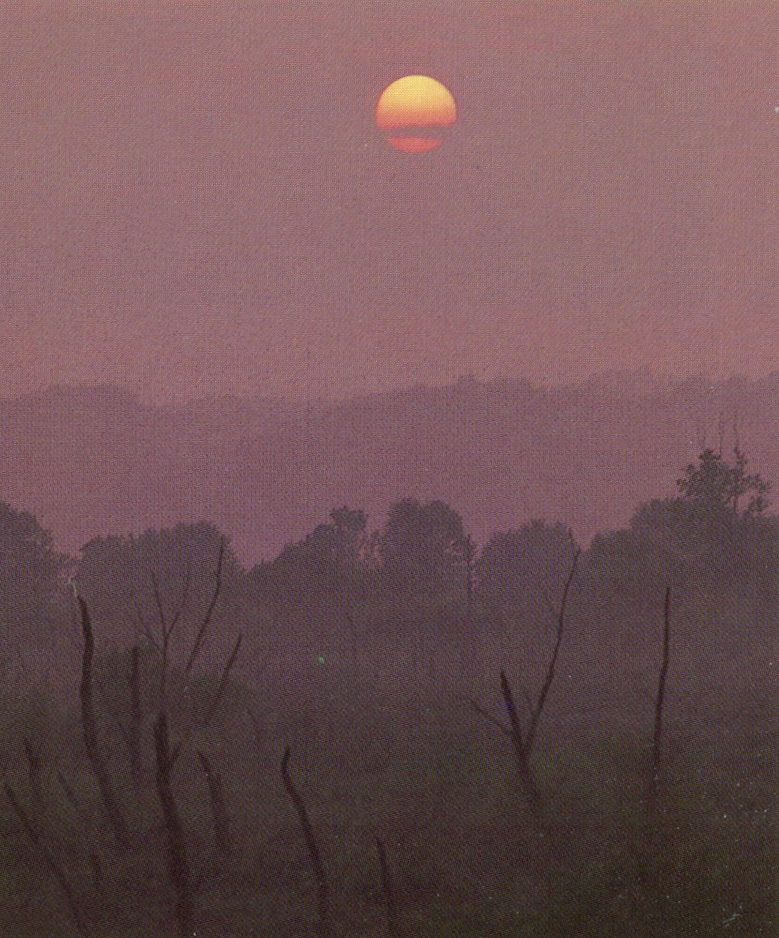

Five years ago ducks and a few species of rare birds were just about the only ones to show much interest in this stretch of fertile river land along the Ohio. Motorists traveling W. Va. Rt. 2 in northern Cabell County would whiz by on their way to places beyond. Except for bird watchers, a few historians and some Marshall University archeology students, most people were unaware of the treasures that lay nearby. In 1988 all that changed.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers purchased 836 acres of the former Gen. Albert G. Jenkins estate including a large wetland to replace waterfowl habitat to be destroyed during expansion of the Gallipolis Locks and Dam. And when it came to deciding exactly how the property should be managed, suddenly everyone had ideas and an agenda.

What resulted was four years of controversy, a war of words among archaeologists, environmentalists, historic preservationists, nature lovers, the Corps, and the W.Va. Department of Natural Resources, which leases and manages the property.

There may not be peace, but at least coexistence.

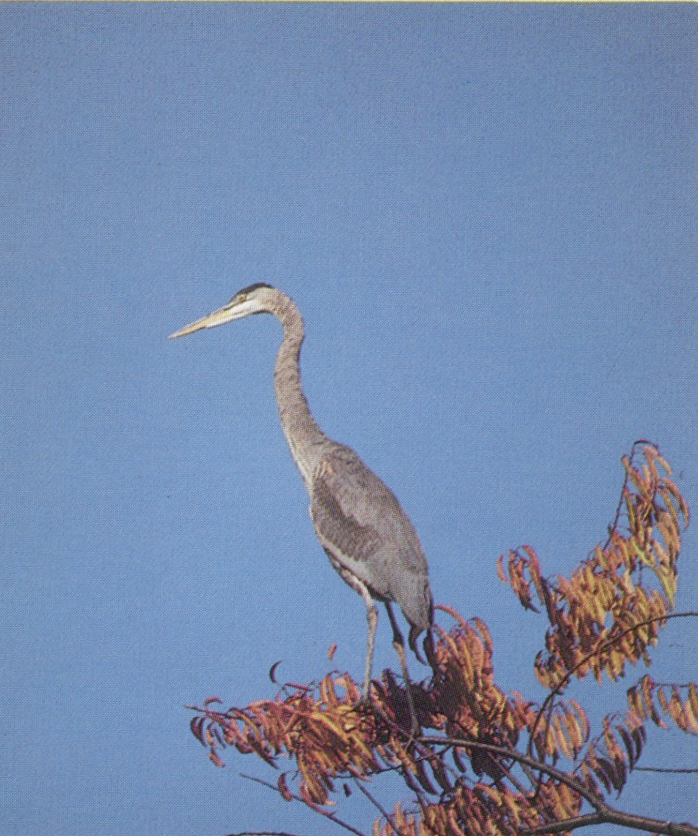

The DNR has renamed the property the Greenbottom Wildlife Management Area and opened it to hunters drawn to the abundance of wildlife. Environmentalists and nature lovers have been given assurances the delicate wetlands and rare birds that live here will be protected.

Digging will continue at several archaeological sites, where artifacts dating from 8,000 B.C. have been unearthed. And the Corps of Engineers has pleased historic preservationists by stabilizing the centerpiece of the former estate: the Gen. Albert Gallatin Jenkins House.

Still, Dr. Elinore D. Taylor, president of the Greenbottom Society, and her group, haven’t given up their fight to see the house restored to its pre-Civil War glory. The society was formed in 1989 to promote the historic preservation and tourism potential of the area.

“The aura around here is just something,” Taylor exclaimed one recent summer evening as she stood on the lawn of the 157-year-old house, explaining her vision for developing the former plantation.

She believes promotion of the environmental, archaeological, and historical significance of the area could attract many tourists each year. “We want to see Greenbottom used to its full potential.”

She said she sees the restoration and public opening of the Jenkins home as the key to any such development.

The DNR currently uses the house as an office and residence for the area’s wildlife manager. Representatives have said the DNR will consider subletting the house and a surrounding parcel of land to the state Division of Culture and History if a feasible plan is developed for operating and maintaining the structure, which is listed on the national Register of Historic Places.

The Green bottom Society has secured $3,000 in matching grants from the Cabell-Wayne Historical Landmarks Commission and the Division of Culture and History to fund such a feasibility study.

The society would like to see the house restored to the way it was in the mid-1800s. Taylor said it could be used as a museum, for meetings, tours and a place to display and possibly sell arts and crafts.

Ultimately she envisions a dock on the Ohio where passengers of the West Virginia Belle could disembark and picnic, tour the house and learn about the area’s environmental and archaeological and historical significance.

“We’ll get the enthusiasm generated if they will just give us the house and the land back,” Taylor said. “Once we get the results of the study, we’ll go to the legislature and the governor to try and get them involved.”

For now, all Taylor and members of the Greenbottom Society can do is wait.

Meanwhile, Mike D. Griffith, a member of the local chapter of the Audubon Society, is doing some waiting of his own. “We’ve been given assurances the existing wetlands will not be disturbed,” he said.

“We’ll be keeping our eyes open to see what’s happening there. People have been going there to bird watch for 20 to 30 years. We’ll know if there are changes.”

Much of the relatively flat terrain along the Ohio was wetlands when the area was first settled. Today, most have been drained and developed for industrial and agricultural purposes.

Griffith also said he is optimistic about the Corps’ construction of a second wetland west of the house.

“Because we are losing wetlands all over the country, building new wetlands is something the Corp and others need to learn how to do.”

Michael A. Friel is managing editor of the Huntington Quarterly.

On the history of the Jenkins family

Like many people today, Captain William Jenkins was drawn to Greenbottom by the fertile land and natural beauty. The Tidewater, Va., operator of a shipping line arrived in the area in 1830 in search of a quieter life – and land.

He found both at Greenbottom. Property was plentiful in what was then western Virginia when Jenkins paid $15,000 for 4,395 acres at Greenbottom.

In 1835 he built a Federalist style home there using bricks made from clay on the property, and from hardwood cut from the surrounding forest. The large house, which faces Ohio, is reminiscent of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

By 1850 the Jenkins estate had become the center of preCivil War social activities in the area. There were frequent dances and parties in the home’s main living room and huge picnics on the lawn. At its peak, the Jenkins Homestead had developed into a large working plantation with 55 slaves.

Captain Jenkins had three sons. The youngest, Albert Gallatin, achieved considerable national prominence. He was a Harvard Law School Graduate who began practicing in 1850, first in Charleston and then at Greenbottom.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1857, where he served until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. A Southern sympathizer, he joined the Confederate Army in the spring of 1861 and was named captain.

In 1862 he was elected as a Virginia representative to the first Confederate Congress, a position he resigned later that same year to accept an appointment as a brigadier general. Jenkins is said to have been the first person to carry a Confederate flag into Ohio.

He was wounded in a battle at Cloyd’s Mountain, Va., and died two weeks later of complications. He is buried in Huntington’s Spring Hill Cemetery.

The Civil War also took its toll on the Jenkins plantation. The financial hardships of post-Civil War society reduced the size of the Jenkins estate to just 150 acres. Jenkins family members continued to live there until 1940, when the general’s daughter, Margaret Virginia Jenkins, died.