Huntington’s mass transit system was born in the late 1880s when the city’s first electric streetcars began operating. But the life of the trolley as a mode of transportation was short-lived.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 10 | WINTER 1992

A century ago the streetcar line was the royal road of travel in urban areas. For a nickel or so one could ride downtown, across town, out into the suburbs, or even to a nearby city. The “trolley,” or electrical streetcar, ran on tracks and used a pole to draw power, usually from an overhead wire. By the 1890s almost every large- and mediumsize city in America had electric streetcars rolling on steel rails down the center of its avenues – and that included Huntington. Electric lights first shone on Huntington’s streets on Nov. 12, 1886. This led city fathers to decide to add the new technological marvel called the electric streetcar to city transportation. Ln June 1888, the Huntington Electric Light and Street Railway Co. was chartered, taking over the Huntington Electric Lighting Company and its task of furnishing the city with electric lights. It was also to build and operate an electric streetcar line by Dec. 15, 1888. To meet the stipulated deadline for streetcar service, tracks were laid up Third Avenue between Seventh and 23rd streets and horse-drawn cars began making several trips daily. What is said to have been the second electric street railway in the U.S. began operation when the line was completed to Guyandotte in 1889. It had 3.5 miles of track with three cars powered by an overhead wire. A Richmond, Va., route had the distinction of being the nation’s first electric car line when it began operating in 1887.

Horses and mules powered a second street railway, The Huntington Belt Line, which ran between the C&O and Ohio River Railroad depots and to the C&O shops from 1890 to 1892, when the two lines were combined as the Consolidated Light and Power Company. “All streetcars were run by electricity thereafter,” states Doris C. Miller in her Centennial History of Huntington, 1871-1971. According to a 1949 Huntington newspaper advertisement for the Ohio Valley Bus Co., the electrification of street railways was opposed by those who “feared the ravages of electricity” and was sanctioned by those who objected to the hard work the horses had to perform. Progress prevailed; the first electric trolley moved through the streets.

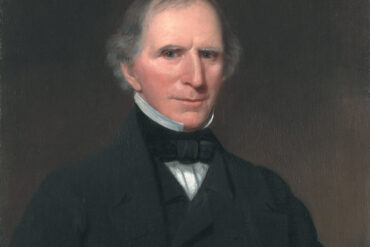

Trolley lines made little progress, or profit, during the 1890s until Huntington lawyer Z.T. Vinson persuaded investors of the need for interurban service between Huntington and Ashland, Ky. He envisioned a consolidated regional company and as an attorney representing railroad and coal magnate Johnson N. Camden of Parkersburg, he interested him in the idea. On Camden’s behalf, Vinson acquired in 1899 the streetcar companies and subsidiary operations serving Catlettsburg and Ashland, Ky., and Ironton, Ohio. By the end of the year, Vinson had incorporated the Ohio Valley Electric Company and had arranged to buy Huntington’s electric railway. A connecting line and bridge were built across the Big Sandy River and service between Huntington and Ashland commenced in July 1903.

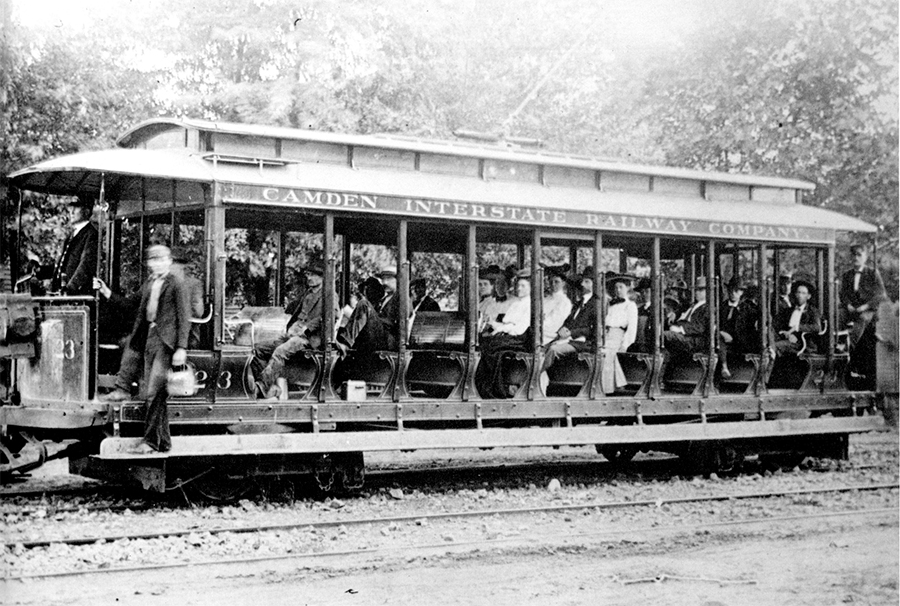

The new streetcar line began at Guyandotte, two miles east of Huntington, and extended through the city and along the Ohio River to Kenova. Here the tracks crossed the Big Sandy into Kentucky and proceeded through Catlettsburg and along the Ohio to Ashland. There a steam ferry carried passengers to Coal Grove on the Ohio side where they boarded cars for Ironton. The entire line covered 27 miles and served a growing industrial area. In order to avoid any intercity conflict over the name and since Johnson Camden owned 90 percent of the bonds, the line was christened the Camden Interstate Railway. The success of the multi-million dollarplus venture was soon demonstrated as the railway began to earn income far in excess of operating expenses. By 1908 Camden and his coinvestors had sold their stock to a Philadelphia interest.

Camden Park, near Huntington’s western limits, was started in 1903 as a picnic grove by the Camden Interstate Railway as a means of boosting its weekend and holiday traffic. At about that same time, the streetcar line established Cliffside, an amusement park that once was located between Catlettsburg and Ashland and which attracted many Huntingtonians.

In 1904 another outfit called the Huntington-Charleston Railway Company obtained franchises over certain streets and avenues south of the C&O mainline in Huntington, and a streetcar line was built in this area. The trolley line served residential routes and ran south on Eighth Street to 12th Avenue as the Ritter Park line. Another line ran east on Charleston Avenue to 20th Street, then south again reaching the entrance to Spring Hill Cemetery by May 1907. These routes were later taken over by the Camden Interstate Railway.

According to a Huntington newspaper article, by 1913 the Camden Interstate Railway “served several routes in Huntington, two lines in Ashland, and operated three amusement parks.” The line “was kept busy when W.Va. was ‘dry’ and Kentucky ‘wet,’ with extra runs constantly being dispatched to handle patrons of taverns in Catlettsburg,” states the newspaper account. Miller said openair cars were used in the summer on some Huntington-Ashland runs of the Camden Interstate Railway.

In October 1916 the Camden Interstate Railway became the Ohio Valley Electric Railway and all streetcar lines were operated in the Tri-State area by this company until bus service was installed in 1933.

A June 1959 Huntington newspaper article remarked that “the earliest streetcars in Huntington carried their destinations in permanent lettering.” Despite this optimism for the future, the lifespan of streetcars in the city was brief.

On June 2, 1924, the Ohio Valley Bus Company was incorporated through the electric railway company. In 1933 F.W. Samworth and a group of associates assumed control of the streetcar line then purchased the Ohio Valley Bus Company from its organizers the following year and began operating streetcars as well as buses. The former company had begun to dispose of its holdings, so bus service began on the same streets where the tracks were coming out.

According to a newspaper article: “On Nov. 6, 1937, the changeover was complete. That night [William] ‘Uncle Billy’ Jordan, who had chopped trees for ties for the horse car line, took the last electric car on its final run from downtown Huntington to Guyandotte on the historic Third Avenue run, back to Vernon Street and then to the car bar on W. 18th Street.”

So it was all over America: With amazing speed and thoroughness, most streetcars disappeared as quickly and completely was they had covered the landscape years earlier.

Doris Miller reports that “After the last streetcar ran in 1937, Huntington became the first city in the state to be served entirely by buses.”

By July 1938 the Ohio Valley Bus Company had 50 buses in operation. In an April 1984 interview, Harold Spears Jr., superintendent of the Tri-State Transit Authority, remembered when the last rail trolley left the streets of Huntington. He said that “the streetcars had to be replaced with buses because the growing city was expanding faster than the Ohio Valley Electric Railway could lay down tracks.”

Spears said that the trolleys that were retired in 1938 “were as simple to operate as the first that appeared on city streets 50 years before, and some drivers had a hard time adjusting to the new gear-and-clutch buses.”

In 1959 OVB coaches, each with a seating capacity of 41, ran “upriver as far at Letart, W.Va., between Ravenswood and New Haven, and down river to Russell, Ky. North of the Ohio River, OVB service extended from Proctorville to Hanging Rock, Ohio,” states the newspaper account. Buses also ran from Huntington to Lavalette.

According to a 1950s newspaper account, the Ohio Valley Bus Company was unique in that it was one of the nation’s few city bus companies whose area of operation was unrestricted, especially in its charter business. “Ohio Valley can run its buses to anywhere in the U.S.,” states the newspaper, whereas nearly all other city bus systems are limited to their own home territory.

In the mid-to-late ’50s, OVB owned as many as 80 buses, including five large cruise-type buses with air conditioning for charters. In 1958, “the company carried 12 million people in its 78 coaches a distance of three million miles,” states a newspaper report.

However, with increased use of private automobiles, ridership on buses declined. Because of a strike, on Oct. 1, 1971, the Ohio Valley Bus Company, ceased operation. In 1972, after the city had been without bus service for more than nine months, OVB turned over its assets to a new public agency, the TriState Transit Authority or TTA. In July 1972 TTA buses began rolling on city streets.

Although more than a half-century has passed since streetcars were last seen on city streets, reminders of Huntington’s streetcar past are still visible. There are trolley tracks in the underpasses on Hal Greer Boulevard and on Eighth Street.

In August 1 984 the TTA purchased two diesel-powered buses that were designed to look like streetcars and called “trackless trolleys.” The trolley replicas had a wood finish, brass rails, etched glass windows, and could hold up to 24 passengers. They were named the “Huntington” and the “Cabell” and were used on routes inside city limits. The cars are now only used for special occasions, according to Vicki Shaffer, TTA general manager.

Shaffer states that the 27-bus fleet of the TTA carries nearly 2,300 passengers daily between the hours of 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., six days a week.

For streetcar fans, some of these mass transit vehicles from a bygone era are preserved in museums. As one writer has stated: “It is perhaps the thoroughness with which trolleys disappeared that makes them stand out so powerfully in the national memory.”