The Story of Huntington’s Old Brewery

By James E. Casto

HQ 13 | WINTER 1993

Before the spread of the big retailers, most stores in these United States were locally owned. Before the fast-food chains, hamburger stands and short-order restaurants were mostly “mom and pop” affairs. Before today’s supermarket, there was the corner grocery. And before a few corporate giants divided up the beer business, many a proud town boasted its own local brewery. Among them was Huntington.

On and off for some 80 years and under three different owners, a complex of buildings on the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and West 14th Street housed a busy brewery that turned out a wide variety of beers enjoyed by generations of thirsty customers.

The brewery originally was constructed in 1891 by the American Brewing Co. Little is known about the company other than its fate: It failed to prosper and soon ceased operation. Shortly thereafter, the redbrick plant that American Brewing had built was purchased by the Fesenmeiers, a family whose name would become synonymous with the word “beer” in the minds of Huntingtonians.

The family patriarch, Michael Fesenmeier, came to this country from Germany in 1851, settling with his bride on a farm near Cumberland, Md. He brought with him an extensive knowledge of beer-making, and he started a small brewery on the farm. The venture was so successful it eventually outgrew the farm and thus was moved to Cumberland.

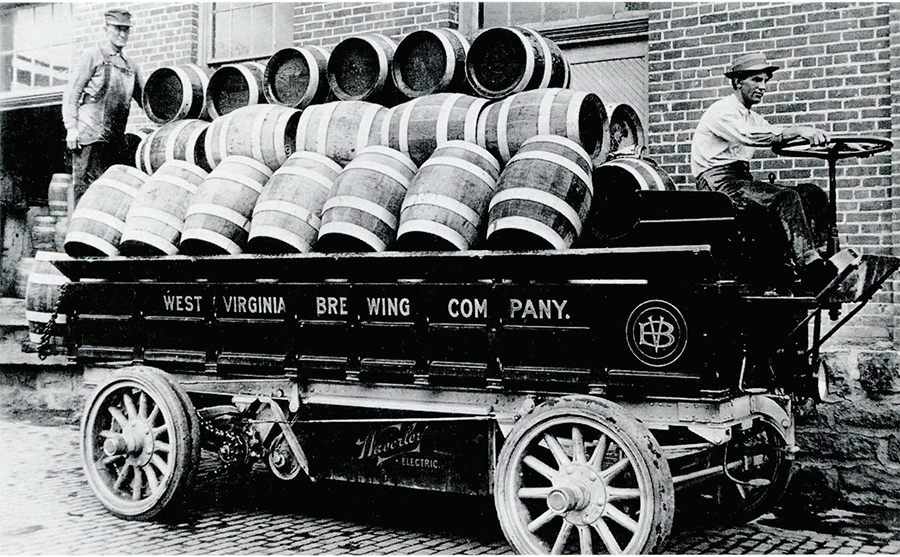

In 1893, Fesenmeier died, leaving four sons – George, Michael, Andrew, and John – along with two daughters, Miss Teresa Fesenmeier and Mrs. Catherine Kearney. In 1899, the Fesenmeiers, along with their brother-in-law John Kearney, bought American Brewing’s defunct brewery here. John Fesenmeier and Kearney moved to Huntington to run the new business. The company’s name was changed to the West Virginia Brewing Co. and the brewery soon was producing “Fesenmeier Brew” and “West Virginia Special Export Beer.”

A 1903 advertisement in the Huntington Herald told readers why beer brewed by the West Virginia Brewing Co. was the drink of choice:

“When the mercury is up, there is nothing that will invigorate and refresh you like a glass of sparkling and delicious West Virginia Beer. For the businessman, the working man, the housewife who attends to her own work and the nursing mother, it is a boon that is appreciated, for it gives strength and refreshment as nothing else will when the heat is oppressive. Brewed by The West Virginia Brewing Co., Huntington, W.Va.”

The late George S. Wallace, the city’s premier historian, relates in his 1941 book Huntington Through Seventy-Five Years that the Fesenmeiers were pleased with their new acquisition, but nonetheless faced a big problem in getting their beer into the hands of customers. You see, the brewery was located, not in the town limits of Huntington, but in Central City, at that time an entirely separate town-with no paved roads linking the two.

“The problem was partially overcome,” reports Wallace, “by establishing a warehouse at 2nd Avenue and 10th Street on the riverbank and shipping carloads of beer and ice by rail from the plant at West 14th Street to the warehouse. This was not satisfactory as the extraordinary demand at times exceeded the shipping facilities.”

Eventually, Huntington and Central City cooperated in the paving of a roadway between the two, but even then there remained a two-block stretch of land at 1st Street, known as the “Neutral Strip,” which was not in the corporate limits of either town and so went unpaved. In bad weather, this stretch turned into such a sea of mud that it was necessary for the brewery to keep a team of horses stationed there in order to pull its wagons through the mud. In 1908, Central City voted to become part of Huntington and the next year saw the city annex the “Neutral Strip.”

In 1905, the brewery was hit by a raging fire that all but gutted it. By the next year, however, it had been rebuilt and was back in business. The flood which hit the city in 1913 also seriously damaged the brewery, but again repairs were made and the beer soon was flowing again.

But the next year saw the State of West Virginia do what neither fire nor flood could do – force the brewery to shut its doors. In 1914, West Virginia enacted legislation prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages. That was five years before the 1919 ratification of the 18th Amendment established Prohibition as the law of the land. In 1910, a would-be purchaser had offered the Fesenmeiers $1 million for their brewery. After West Virginia went “dry,” the brewing equipment was dismantled and sold at a $250,000 loss.

John Kearney had died in 1913, so it was up to John Fesenmeier – now known to one and all as “Uncle John” – to carry on as best he could. He decided to covert the closed brewery into a meat-packing plant, and so in 1916 the Fesenmeier Packing Co. opened for business, with many of the company’s veteran employees on the payroll. The meat-packing business never really caught on and was closed on John Fesenmeier’s death in 1920. The next year, Michael Fesenmeier moved to Huntington from Baltimore and reopened the plant as a cold-storage facility for perishable produce.

The 18th Amendment had been immediately followed by legislation to enforce it, the Volstead Act, named after its congressional sponsor, Rep. Andrew Volstead of Minnesota. Congress overrode a veto by President Woodrow Wilson and the act went into effect on Jan. 16, 1920. Suddenly, America had a whole new industry- bootlegging. By the mid-1920s, the making

and selling of illegal liquor and beer was a $2 billion a year endeavor that employed a half million people.

But demands for an end to what some called the “noble experiment” of Prohibition grew louder and louder. Finally, the 21st Amendment, repealing the 18th, was ratified and went into effect in December of 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first year in the White House.

With the repeal of Prohibition, the Fesenmeier family spent $350,000 to renovate and modernize the old brewery, expanding its capacity to 100,000 barrels of brew a year and designating the rejuvenated company the Fesenmeier Brewing Co. The first kegs of post-Prohibition beer were rolled out on May 10, 1934, and for the next three decades the brewery would be kept busy producing “West Virginia” brand pilsner beer and ale. While plans were afoot to reopen the brewery, Michael Fesenmeier died and was succeeded as company president by a nephew, Frank Fesenmeier, eldest son of the late John Fesenmeier.

In 1949, the Fesenmeiers celebrated their 50th anniversary in business and The Herald-Advertiser assigned a young reporter – Ernie Salvatore by name – to write up the event. Before long, Salvatore would move to the sports department, where he would become one of the best-known sportswriters in the city’s history. But at this point in his career, Salvatore was a cub reporter subject to the city editor’s beck and call. And so, he found himself at the old brewery interviewing Frank Fesenmeier, who proudly boasted: “This is only the beginning. The first 50 years are the hardest. Now we’re ready to begin.”

Actually, though neither Frank Fesenmeier nor Salvatore knew it at the time, the days were numbered for Fesenmeier and countless other small brewers. Unable to compete against the big beer makers with their multi-million dollar advertising budgets, more and more small brewers were forced out of business. In just a few short years, the number of breweries in the United States dropped from 2,000 to 400.

At its peak, the Fesenmeier brewery sold nearly 30 million bottles and cans of beer a year. Its two dozen trucks delivered beer to taverns and retailers within a 100-mile radius of the city. The company’s advertising slogan – “West Virginia: That’ll Win Ya!” – became a familiar refrain in the region. But as the 1950s gave way to the 1 960s, sales steadily eroded, with the local brewer feeling the steadily increasing pressure of competition from the national brands.

By 1968, the Fesenmeiers could read the writing on the wall and did something that once would have seemed unthinkable: They sold the brewery. The purchaser was Huntington businessman Robert B. Holley and a group of local investors. The purchase price was not revealed but Holley told The HeraldDispatch that the property-a full city block, with a maze-like arrangement of buildings – had a replacement value of $2.5 million. The brewery’s sales, he said, were in excess of $1 million a year.

The company was rechristened the Little Switzerland Brewing Co. and the new owners spent$250,000 to spruce up the old plant, giving the exterior a Swiss motif. Initially, it continued to sell beer bottled with the familiar “West Virginia” label but soon it introduced a new brand of its own, “Charge,” described as “The Bold American Premium Beer.”

Bob Holley and his partners officially took over the brewery on April 1, 1968 – April Fool’s Day. The date may have been significant, for the venture seemed ill-fated from the first. Sales lagged, bills mounted. By February 1970, Holley was lobbying the West Virginia Legislature for a tax credit and warning that, without the credit, the state’s only brewery could be forced out of business. Thirsty souls happily flocked to Charleston’s old Daniel Boone Hotel for a party thrown by Little Switzerland so legislators and others could “sample” the brewery’s product. Nevertheless, the tax credit failed to pass. Creditors filed suit, forcing the company into bankruptcy. In October, the old brewery closed its doors for the last time.

And in July of 1972, a wrecking crew wrote the last chapter of the brewery story – leveling the once-handsome complex of buildings to make way for a shopping center.