Huntington’s West End celebrates 100 years

By James E. Casto

HQ 14 | SPRING 1993

Like other cities, Huntington is a community made up of many individual neighborhoods. But today few people realize that two of those neighborhoods – Central City and Guyandotte – once were separate cities, with their own mayors, police, post offices and all the other hallmarks of a municipality.

The village of Guyandotte was granted a charter by the Virginia General Assembly in 1810, and for many years flourished as a river landing and a stagecoach stop on the old James and Kanawha Pike. But the village’s fate was sealed in 1869 when rail baron Collis P. Huntington opted to locate the western terminus of his Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, not in Guyandotte, as had been widely anticipated by the locals, but on a mostly vacant piece of real estate along the Ohio River just to the west. It was only a matter of time before the city that grew up there – Huntington -would eclipse and eventually absorb Guyandotte.

The story of Central City is very different from that of Guyandotte – and a tale that demands special attention this year because 1 993 marks the 100th anniversary of Central City’s birth. It was in the early 1890s that a group of local investors organized the Huntington and Kenova Land Company, bought several farms west of Huntington and laid out a new town, which they optimistically christened Central City. The name came from the new town’s location, roughly midway between Guyandotte and Catlettsburg, Ky. The new town’s backers were enthusiastic about their venture. After all, if Collis P. Huntington could start a new town from scratch, why couldn’t they?

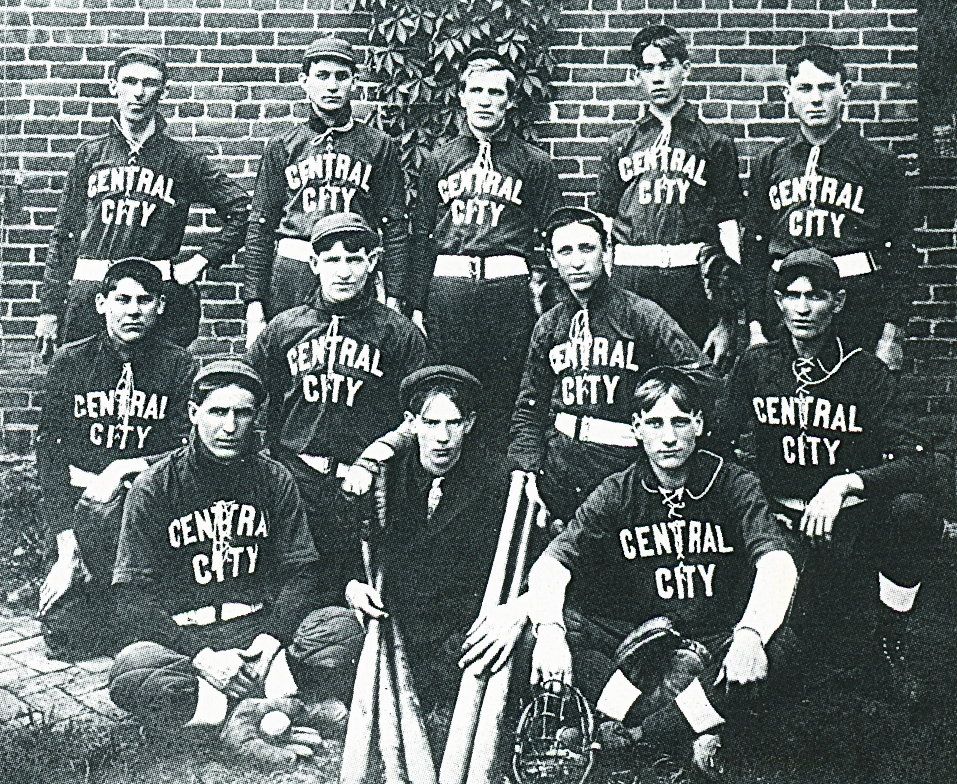

On July 31, 1893, upon the petition ofJohn S. Farr and others, the Cabell County Circuit Court officially recognized Central City as an incorporated municipality. The court’s order was challenged by a plaintiff identified in court records as C. S. Elder. The details of his objections are lost in the mists of time. In any event, his challenge, though carried to the state Supreme Court, failed, and on September 11, the new city’s backers held an organizational election.

M. V. Chapman was elected mayor. Chapman, it might be noted, was the father ofFloyd S. Chapman and the grandfather of Martin V. Chapman, both of whom eventually would serve as mayors of Huntington. Farr, Thomas Sikes, Hunter Evans and D. H. Brinker were named councilmen. George M. McDermitt was elected town recorder, and A. G. Plymale, police sergeant. Others active in the founding of Central City included George McKendree, J. L. Caldwell, G. F. Miller and Z. T. Vinson. Apparently it was McKendree who had the inspired idea of using Rufus Cook’s well-designed plan for Huntington as the guide for laying out Central City’s streets.

Cook, a noted Boston engineer who had been personally retained by Collis P. Huntington, laid out a grid-like plan with wide avenues running parallel to the Ohio and conveniently intersected at regular intervals by connecting streets. A strip of vacant land left between Huntington and Central City would become known as the ‘Neutral Strip’ and for many years would be a muddy barrier between the two cities and their separate street networks.

A brick city hall was constructed at the corner of Madison Avenue and W. 14th Street. Still standing today, it long has housed the Huntington Fire Department’s St. Cloud Station.

Like early Huntington, Central City would prove to be a magnet for manufacturers.

The glass industry was one of the first arrivals. In 1891, L. H. Cox opened the West Virginia Window Glass Co., which produced handsome hand-blown window panes. The plant, located in the block bounded by Jefferson and Madi- son Avenues and W. 15th and W. 16th Streets, went under in 1894 and was taken over by Forbes Holton, who operated it under the name Union Glass Works until 1904. It then was acquired by Anton Zihlman, a native of Switzerland, and operated as the Huntington Tumbler Co. until 1932. In its heyday, the plant exported tumblers, goblets and other glassware all over the world.

Even before Cox built his glass plant, another glassmaker, Addison Thompson, bought the block bounded by Washington Avenue and the river and W. 14th and 15th Streets, and there opened a plant where he made a number of glass products, including a popular hobnail-design.

In 1899, Thompson sold his plant to a photographer, D. E. Abbott, who moved his already-thriving picture framing, enlargement and portrait business there. At one time, the large plant fabricated every manner of fancy frames for customers all over the country. On Abbott’s death, the business was left to the employees. Today, Helen Napier operates it as a retail picture-framing shop, located in handsome new quarters at 709 W. 14th Street.

There was a brick plant at Four Pole Creek between W. 9th and 10th Streets, which was started by George and Morris Arthur and , in 1891, was taken over by A. J. Crawford. Later it became the Central Brick Company and, still later, the Huntington Red Brick Company. It went out of business in 1917.

Much of the commerce in Central City involved wood products. In 1894, William Seiber began the Central Veneering Co. at W. 13th Street near the river. The plant would be a busy place for many years. In 1917, it was purchased by the Wood Mosaic Poplar Veneer Co. of Louisville, which continued to operate it for more than 50 years, eventually shutting down in 1969.

There was a broom factory, another busy plant turned out ax handles and yet another produced bungs. Today, most people would have no idea what a bung might be. But in an era when whiskey was shipped and sold in barrels, the cork-like piece of wood that was used to plug the hole in the barrel was a small but important item. And for a few short years, Central City was the “BungCapital of the World.”

John Hale originally operated his bung plant on the Little Kanawha River in Wirt County but, when it burned, he was lured to Central City by the offer of a new plant site at a bargain price. And so, in 1894, the Central City Bung Co. opened for business at Monroe Avenue and W. 14th Street. Six years later, it was acquired by the United States Bung Co. of Cincinnati. The plant’s new owners installed bung-carving machinery that was so secret that the windows were barred and all the doors zealously guarded, lest competitors copy the design. The plant was so successful it all but cornered the world market for bungs. However, the arrival of Prohibition ended the demand for bungs and when Prohibition was repealed, distillers turned to shipping and selling whiskey in bottles, not barrels.

Another early arrival on the Central City scene was the Beader Box & Lumber Co., established by two brothers-in-law, John Graham and M. L. Duncan. When Graham sold his interest in the firm, the name was changed to the Duncan Box & Lumber Co., which is still operated by the Duncan family.

Also still in operation is Heiner’s Bakery. But long gone, alas, is one of Central City’s most-famous landmarks, its brewery.

Heiner’s today is a big business, with a sprawling Adams Avenue plant that covers a whole square block, a workforce of more than 300 employees and a fleet of 90 trucks that delivers bread products to retailers and restaurants throughout much of West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky. That’s certainly a far cry from the one-room, one-man bake shop that C. W. Heiner started in the old Central City Hotel building in 1905.

The American Brewing Company came to Central City in 1891 and built a plant at Madison Avenue and W. 14th Street. The venture failed and in 1899 the brewery was purchased by the Fesenmeier family, which would successfully operate it until West Virginia went “dry” in 1914. Reopened with the repeal of Prohibition in 1934, the brewery again was busy for many years but eventually succumbed to the competition from the big national brands. It ceased operation in 1971 and was demolished to make way for a shopping center. (For more on the subject see “Fesenmeier’s: The Story of Huntington’s Old Brewery” in the Winter 1993 issue of HQ.)

ln 1908, Huntington started a push to annex the areas around it. The citizens of Guyandotte rejected the idea in a 1909 election but in a second vote, in 1911, agreed. Central City’s town council showed no such reluctance, adopting a merger resolution on December 7, 1908. It took six months to hammer out the details, but on June 3, 1909, Central City officially passed into the history books.

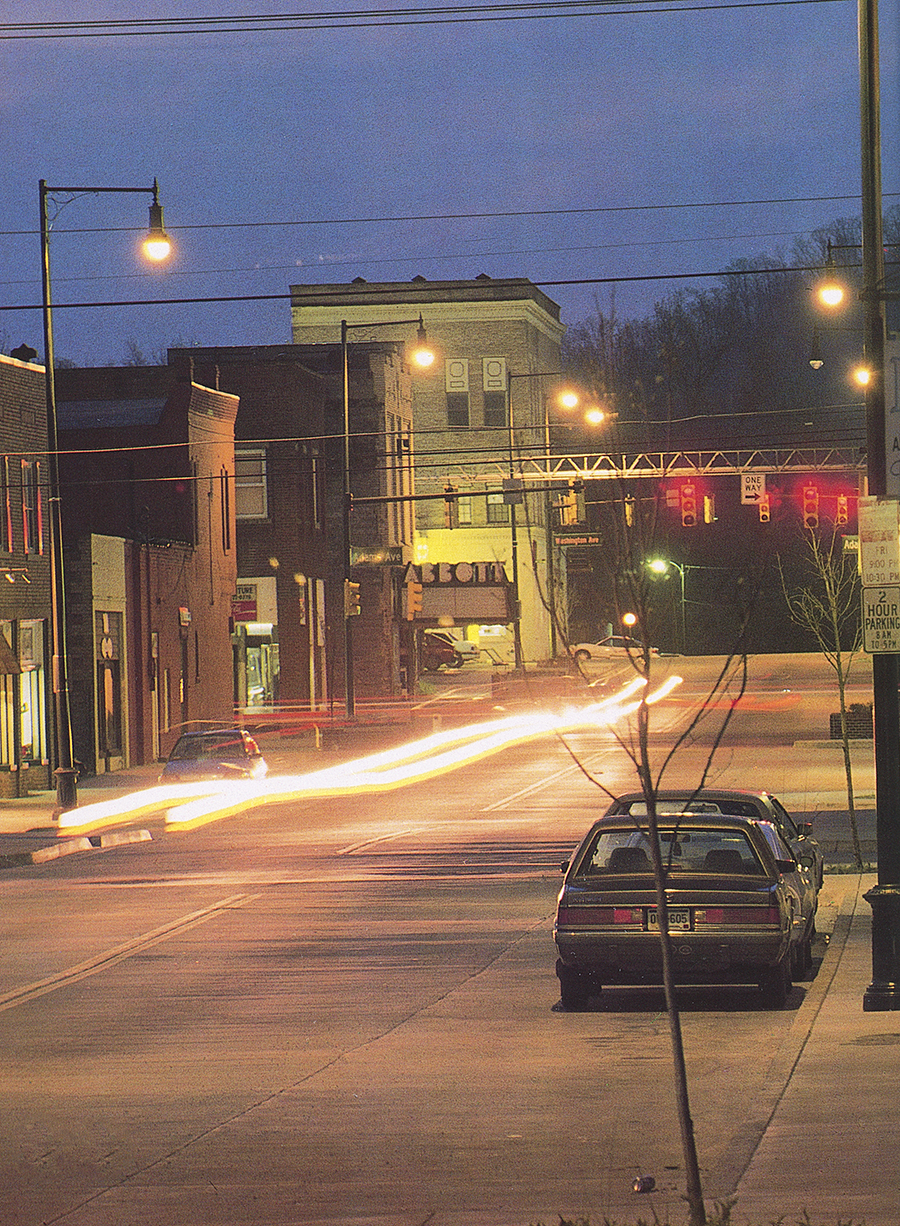

In the decades since, the neighborhood has had its ups and downs, but by the 1970s it was in seedy shape. Most of the plants that once were Central City’s pride long since had closed their doors, succumbing to the same ills that claimed so many factories in the nation’s “Rust Belt.” A once-busy retail community had been devastated by the arrival on the scene of the discount chains. And the neighborhood was one most people shunned, not just at night but even during the day.

Today, however, the old Central City neighborhood is undergoing a remarkable revival. In large measure, that recovery has been sparked by an infusion of tax dollars. But, more importantly, there’s also a new attitude evident on the part of those who live and work there – a clear determination to stop the area’s downhill slide.

In 1983, the City of Huntington adopted the “Old Central City Plan,” and embarked on a public-workers program to improve and widen W. 14th Street, providing new sidewalks, curbs and lighting. The project was broken down into three phases, with the first and second phases already completed and the third scheduled this year. After that the plan calls for paving 90 off-street parking spaces and constructing a children’s park on the former Baltimore & Ohio Railroad right-of-way, long a trash and weed-infested eyesore. When completed, the project’s cost is expected to top $ 1.4 million.

At the same time, property owners – some using low-cost, city-sponsored loans – have been busily sprucing up their buildings, and new businesses are springing up. In June of 1992, the city interviewed 19 businesses owners located on W. 14th Street and found that 14 had opened since the advent of the redevelopment program. All said the prime reason for their decision was the neighborhood’s dramatically improved appearance.

Yesterday’s gloomy junk stores have given way to attractive antique shops. And today it’s not at all unusual to spot an out-of-state tour bus or two parked in the neighborhood. Many tourists visit Huntington to ride the West Virginia Belle, tour the local glass plants, visit the nearby Tri-State Greyhound Park-and forage for antiques in the shops on W. 14th Street.

Area antique dealers and other business people have banded together to form the Old Central City Association and have undertaken an ambitious promotion effort aimed at luring not just tourists but also local shoppers to the refurbished neighborhood. Included is “Old Central City Days,” held each year on the last weekend in July to commemorate the town’s founding. The group plans to pull out all the stops for this year’s celebration, set July 30 through August 1, since this will be Central City’s 100th “birthday.” The association’s president is Sally Cyrus of Cavendish-Cyrus Hardware Co., 515 W. 14th Street. Founded in 1928, Cavendish-Cyrus has been retailing hardware, tools, paint, nails and what have you for 65 years. Nancy Heiner of Heiner’s Bakery is vice president and Jim Wiseman of Kramer’s Photo Supply is treasurer. The association’s secretary is Lola Miller of the Cabell County Public Library’s West Huntington branch at 901 W. 14th Street.

Built in 1990 at a cost of nearly $500,000, the attractive new branch library replaced a storefront location in operation since 1 968 and has become another key element in the neighborhood’s rebirth. Library visitors may not only browse through a collection of 22,000 books but also enjoy a growing mini-museum of photographs, newspaper clippings and memorabilia chronicling the history of Central City – a little town that’s officially long dead but obviously far from forgotten.