By Sara Leuchter Wilkins

HQ 15 | SUMMER 1993

The bustling city ofHuntington, West Virginia was barely two decades old when the young black man who was to become one of its most accomplished citizens first laid eyes on his new home. He had ventured in from the coal fields of Fayette County to greet his family, who moved to Huntington from rural western Virginia, lured by the promise of economic opportunity and rumors of a proposed high school for black students.

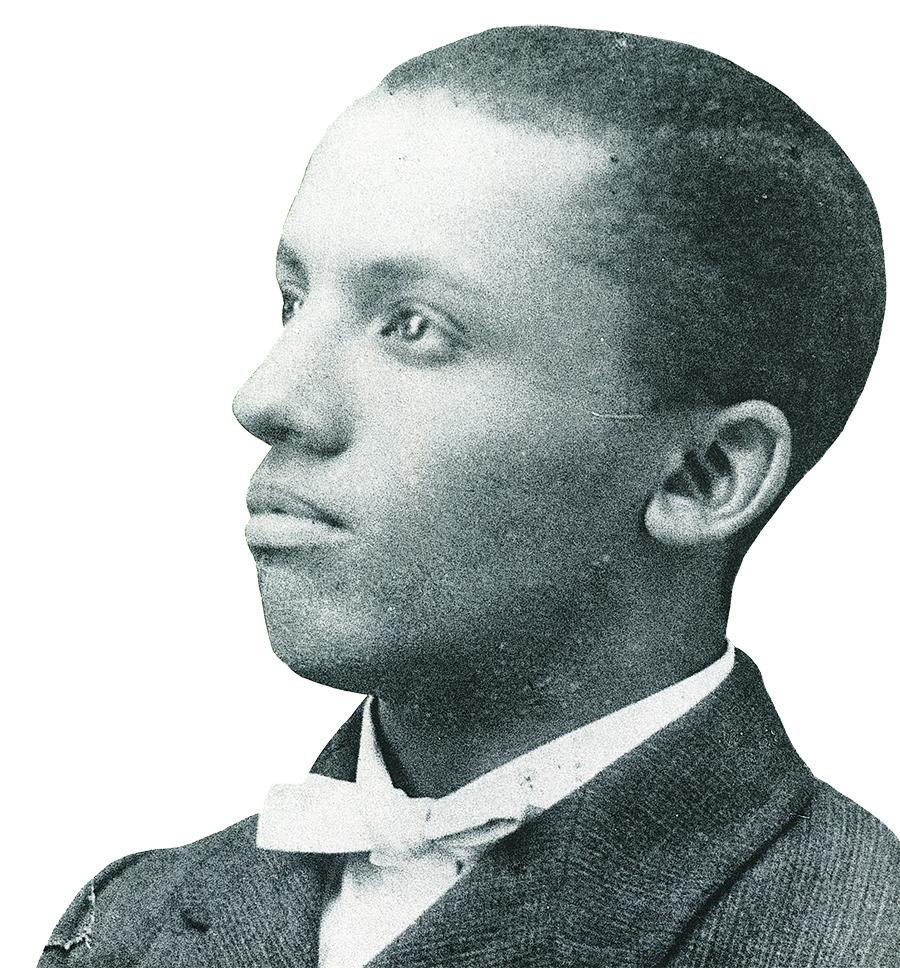

And on that wintry day of his family reunion in 1892, 17-year-old Carter G. Woodson vowed to return to Huntington as soon as he could to further his education.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, now universally acknowledged as the “Father of Black History,” blossomed from humble beginnings as a Virginia farm boy to international prominence as a noted educator, author, editor and scholar. He authored some 16 books on the history of blacks in the United States including The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, The History of the Negro Church and The Negro in Our History.

In addition, Woodson founded The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now The Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History) in 1915 and was founder and editor the following year of the Journal of Negro History. In 1937, Woodson began the Negro History Bulletin and served as it editor. Both publications are still printed today.

Also, in 1926, Woodson began the process necessary to publicly recognize the contributions of black Americans to U.S. and world history. He selected February as the time for an annual celebration because it was the month both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass (a former slave who became a respected orator and social reformer) were born. Subsequently, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded Woodson the Spingarn Medal, which is given annually to an American of African descent judged to have made the the greatest contribution to Negro advancement. What Woodson began as “Negro History Week” in February of that year is now celebrated as “Black History Month.”

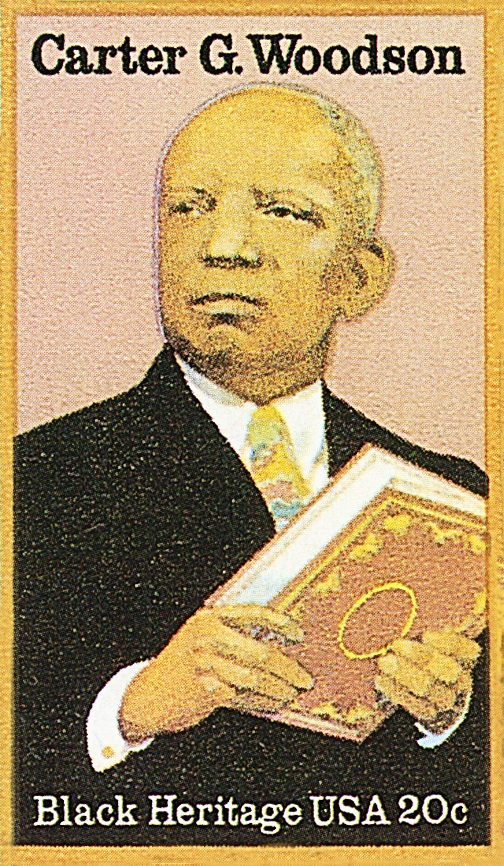

Today, Woodson’s papers are housed in Washington, D.C.’s Library of Congress. In addition, his home/office in that city is a national historic landmark, a branch of the Chicago Public Library is named for him and he appears on a U.S. postage stamp honoring black heritage. On October 5, 1991, Woodson was inducted into Huntington’s own Wall of Fame.

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875, in New Canton, Buckingham County, Virginia. His parents, both former slaves, were married in 1867. His father, James Henry Woodson, though medium sized, possessed an air of power and self-worth. His mother, Anne Eliza Riddle, was short and slender with eager eyes. Woodson’s siblings included elder brothers William and Robert Henry, and sisters Cora, Bessie and Susie.

From early childhood, Woodson was enthralled by tales of relatives and their first-hand accounts of slavery and the Civil War. He listened to stories of his father’s escape across Union lines and the heroic deeds he performed as a member of the Union Army. Woodson reveled in the tales of his grandfather, Henry Riddle, who saved the life of his white half-brother by hiding him on his riverboat during the war. And he was shocked by the account of his grandmother being sold by her master to pay off some debts.

These stories and many others whetted Woodson’s appetite to learn more about /the past. He longed to read so he could find answers to his questions. In the evenings, he would try to recognize letters from an old Bible. Determined to succeed, he taught himself to read by the time he was eight.

Woodson’s family remained in Virginia through the early 1870s. Within a few years, however, they learned of a new city on the Ohio River, called Huntington, in the state of West Virginia, where wages were said to be generous. The young couple packed their belongings and joined a group trekking through the mountains to the Ohio River.

Meanwhile, Woodson and his brother Robert had taken jobs with the Chesapeake & Ohio railroad, helping to build a railway from Thurmond, in Fayette County, W.Va., up to Loup Creek. When they discovered higher wages could be earned in neigh- boring coal mines, the brothers joined a group of laborers who were relocating to the mines at Nutallberg. Within six months, word came that the rest of the family had settled in Huntington, and at his first opportunity, Woodson went to see them.

Despite the fact that Woodson was impressed by his visit to Huntington, he also knew he had a responsibility to contribute to the family’s financial needs and returned to the mines vowing to settle in Huntington when the family could afford it.

During his years in Nutallberg, Woodson was befriended by an elderly black miner named Oliver Jones. Jones was a quiet, intellectual who had been a cook in Richmond before the war. His house in Nutallberg was crammed with books detailing the achievements of blacks. Important people often called on Jones to discuss how blacks could become full and contributing citizens of the nation which had given them freedom, but little else. Woodson, who was present at many of these meetings, remained determined to get an education and pursue these important issues.

Finally, in the fall of 1895, Woodson was financially able to return to Huntington to fulfill his dream of attending school. The city that greeted Woodson seemed a booming metropolis, more than 10,000 strong with grand, new buildings. The foundation had just been poured for the new Cabell County Courthouse. The streets had finally been paved, a trunk sewer line had been installed and street lights were placed on the corners of Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Streets at Second and Third Avenues. The Bell Telephone system had secured a city franchise and railway cars ran along Fourth Avenue to Tenth Street and Sixth Avenue to Sixteenth Street. The city even offered free mail delivery.

In addition, Marshall College boasted a number of large buildings including a fine bell tower and a brand new brick building containing six classrooms had been erected to house Douglass High School.

Carter Woodson, just months shy of his twentieth birthday, was finally seeing his dream come true. He entered Douglass without any prior formal education, but proved to be such an exceptional student that he graduated in just two years. He immediately enrolled in Berea College in Kentucky to earn a teaching certificate, and after two years of study, became a teacher in the small town of Winona in Fayette County, West Virginia.

In 1900, Woodson triumphantly returned to Huntington to assume the duties of teacher and principal at Douglass High School. When his sister Bessie graduated from Douglass in 1901, Woodson proudly signed her diploma.

But Woodson craved more education. He was granted a leave of absence from Douglass in 1902 to attend the University of Chicago. A year later, bolstered by the transfer of college credits from Chicago, Woodson was awarded a bachelor of literature degree from Berea. He then resigned as principal of Douglass High School to further his studies in Chicago.

In October of 1903, Woodson received an unexpected letter from the Office of the Chief of the Bureau of Insular Affairs in Washington, D.C., offering him an appointment as a teacher of English in the Bureau of Education for the Philippine Islands, at an annual salary of $1,200. Woodson, unable to decline this extraordinary opportunity to see the world, accepted the two-year appointment. His experience there was so positive that he asked for a second two-year appointment in 1905, but a nagging stomach problem finally forced him to return to the United States in 1907.

Woodson resumed his education at the University of Chicago and was awarded a master of arts degree in 1908. He then enrolled at Harvard University to pursue a doctorate in history, which he earned in 1912, becoming only the second black man in the school’s history to receive such an honor – the first was W.E.B. DuBois.

Woodson said a Negro was capable of graduating from Harvard or any other university with a feeling that he belonged to a part of the human race, which many believed had never contributed anything of value to America or the world. But he insisted that it was the Negro’s obligation to do something about these misconceptions by writing, publishing and promoting his own history as an integral part of man’s experience. “The knowledge of the Negro, like charity, should begin at home,” Woodson asserted.

While writing his dissertation, Woodson moved to Washington, D.C., where he taught high school French and Spanish. He continued there after receiving his doctorate, while simultaneously writing his first book, The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, published in 1915.

“When I arrived in Washington, D.C., and began my research, the people there laughed at me,” Woodson recalled in a rare instance of writing about himself, “especially my ‘hayseed’ clothes. At the time I didn’t have enough money to pay for a haircut. When I, in my poverty, had the ‘audacity’ to write a book on the Negro, the ‘scholarly’ people of Washington laughed at it.”

But ironically the success of the book gave Woodson the courage to proceed with a new venture he had been considering- the establishment of an association dedicated to the history of black people. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History finally became a reality in September, 1915. Within a year, the Association had launched a new publication under the editorship of Woodson, entitled The Journal of Negro History.

In 1918, Woodson was named principal of Armstrong Manual Training High School in Washington. He also published another book, A Century of Negro Migration. The following year, he became Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Howard University, a position he held for two years. From 1920-21, Woodson taught at the West Virginia Colored Institute (now West Virginia State University).

Woodson was now able to visit his family in Huntington with greater frequency. He marveled at the city’s rapid growth. A new wing for the Courthouse and a bridge spanning the river at the north end of Sixth Street were in the planning stages. Huntington boasted both a new City Hall and Chesapeake & Ohio passenger station. And the teachers’ college at Marshall had conferred its first degrees.

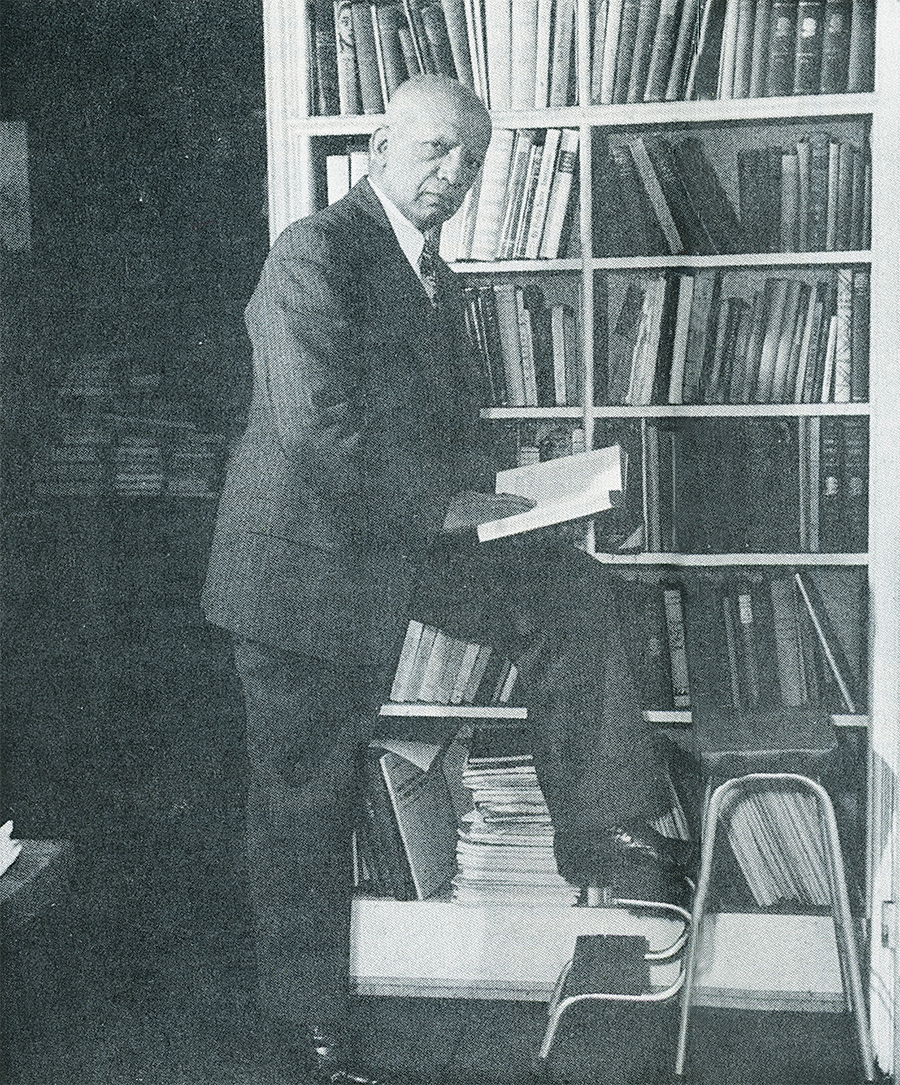

Woodson continued to entertain ambitious ideas, including the formation of a publishing company to produce books exclusively about blacks. On May 28, 1921, he established The Associated Publishers. In 1922, after his Association for the Study of Negro Life and History received grants of $25,000 each from the Carnegie Corporation and the Laura Spelling Rockefeller Memorial, Woodson retired from teaching to devote himself entirely to the work of the Association. He also continued to write books on the American black experience.

Despite his many works and journals, Woodson was not convinced that his message was reaching a broad audience. “We need a spectacular gesture to reach the large public,” he said in 1926. “Since we have Boy Scout Week, Clean Up Week and dozens of others, why not try Negro History Week?” he asked. Woodson then designated a week in February to commemorate the contribution of blacks to American life and culture. Schools throughout the country greeted the idea with enthusiasm, displaying books, putting on plays and skits, engaging lecturers and publishing newspaper articles.

As a result of Negro History Week, people clamored for a more popular magazine than Woodson’s Journal. He responded in 1937 by creating a magazine with more illustrations and less scholarly articles, called the Negro History Bulletin. He then turned his sights toward producing an encyclopedia, called the Encyclopedia Africana, to be devoted entirely to blacks.

In his later years, Woodson continued to write, lecture and edit. He lived to see a black man become a full professor at Harvard University and a black graduate from the United States Naval Academy. But sadly, he found that intolerance and hatred still existed and, in 1950, a tragic incident became too much for him to bear.

On April 1 of that year, Dr. Charles Drew, a surgeon on the faculty of Howard University, was injured in an automobile accident in North Carolina. Drew was the man who, in 1941, discovered the use of plasma for blood transfusions. Under his direction, the American Red Cross set up blood banks to save thousands of soldiers injured during World War IL Because of his discovery, hospitals throughout the world were able to save countless lives. But Dr. Charles Drew was a black man, and when injured in the accident in a southern state, no hospital would admit him as a patient. He subsequently died from a loss of blood when a transfusion would surely have saved his life.

Upon hearing this news, Woodson collapsed from the shock and died alone in his room the following night. He left behind a great legacy not just for blacks but for all Americans. His indefatigable spirit and thirst for knowledge had enriched the lives of generations and will continue to do so for untold generations to come.

To recognize the unique contributions of one of Huntington’s greatest sons, the Carter G. Woodson Memorial Foundation was formed in 1986 by former Huntington Mayor Robert Nelson. Comprised of area leaders, the foundation’s goals include: 1) a life-size bronze statue of Dr. Carter G. Woodson to be located within a park setting; 2) a $60,000 scholarship endowment for the support of both undergraduate and graduate scholarships at Marshall University for outstanding black students; and 3) the Carter G. Woodson Bibliographic Center for Af and Collections, in cooperation with the Special Collections Department of the James E. Morrow Library, to contain a comprehensive collection of works by and about the “Father of Black History.”