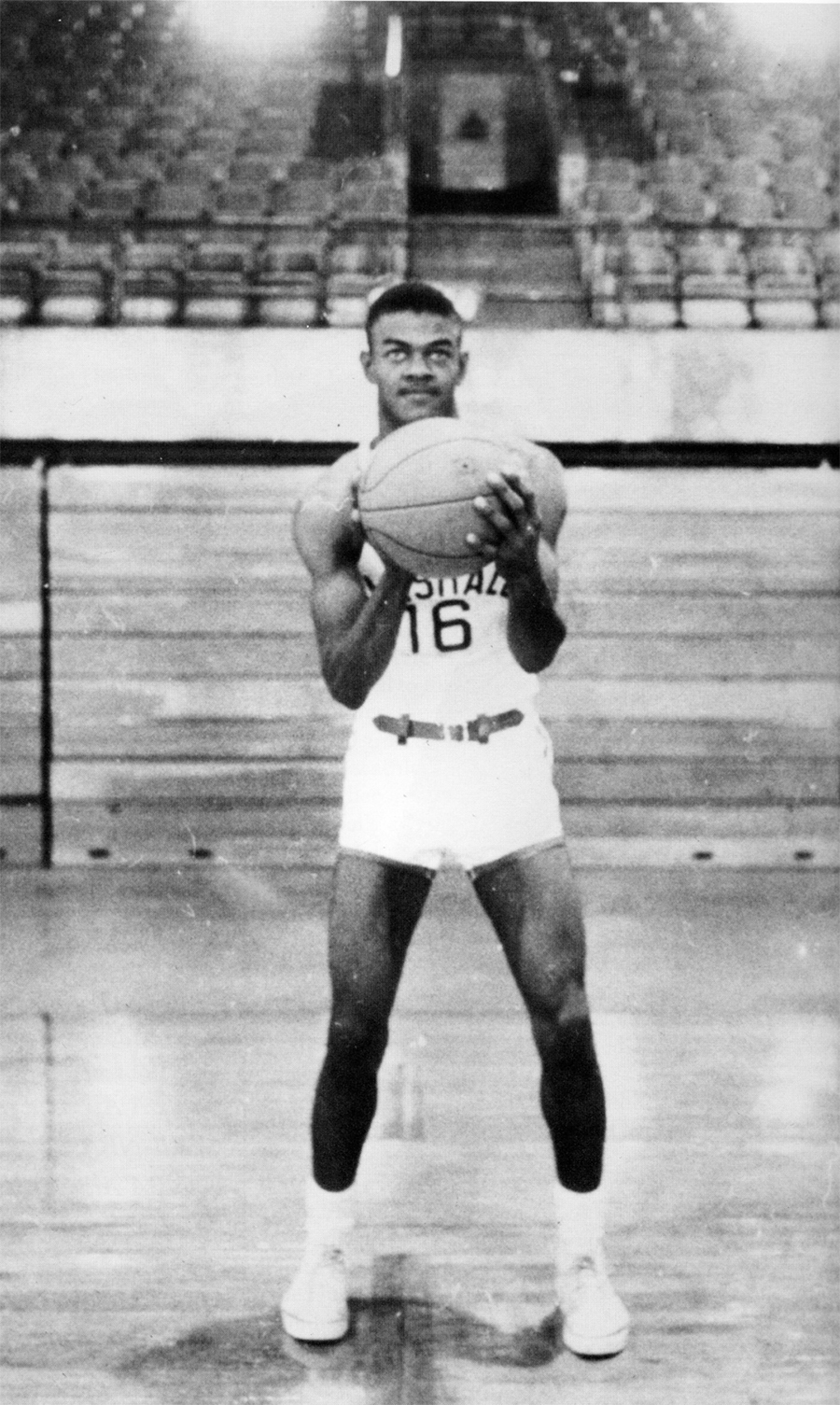

Hal Greer broke West Virginia s color line and went on to fulfill his destiny as a pro basketball Hall of Famer.

By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 18 | SUMMER 1994

In 1954 Harold Greer, youngest son of the Doulton Avenue Greers, shattered the color line in West Virginia when he accepted a basketball scholarship to what was then Marshall College.

Thus began a quiet but distinguished journey that would end 28 years later with Greer’s induction into the James E. Naismith Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass. That’s where basketball was born and where he remains Marshall’s sole representative.

The journey wasn’t easy. They seldom are when one is a social trail blazer. Especially if one doesn’t fit the role. Hal certainly didn’t. His wasn’t a commanding presence. Forty years later it still isn’t. He’s still the quiet, shy, somewhat distant person of his youth.

In fact, he literally dropped out of sight five years ago following some serious financial reverse. At the time he’d been living in Germantown, Pa., an upscale Philadelphia suburb.

Today he’s reportedly living in a suburb of Richmond, Va. But confirming that has been difficult. His surviving brothers and sisters have dropped a cloak of secrecy over the whereabouts of their once celebrated sibling. So, in that sense, little has changed from that historic day Hal Greer breached the white wall surrounding the Marshall campus.

“That poor boy,” Mrs. Tula Greer said. “My heart used to go out to him. He’d come home at night too tired and too upset to eat, and he’d tell me he didn’t want to go back ‘over there,’ that he felt like an outsider and that he wished he had gone to Elizabeth City Teachers College like he planned. But I’d say to him, ‘Harold, don’t be foolish. You’ve got to go back tomorrow. If you don’t you’ll be making a big mistake.’ And, so he’d get up in the morning, eat his breakfast, and I’d hurry him along through the door to make sure that he got ‘over there’ on time. That’s how he got his nickname in the papers, ‘Hurryin’ Hal’ Greer.”

Eli Camden Henderson, for his particular time in history, was neither a bigot nor a humanist, but a very practical man. Thus, the Marshall coach made no moral judgments on the U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down school segregation. Instead, he simply used it to his own advantage. After making several personal scouting expeditions around Huntington to see Hal play, and fortified by private conversations about him with Zelma Davis, Hal’s great high school coach at Douglass, Cam offered the young man a scholarship. Marshall’s gain was to be Elizabeth City (N.C.) State Teachers College’s loss. Hal had wanted to follow in the footsteps there of his brother, the great J.D. Greer.

“Until Harold grew up I’d have to say that J.D. Greer was the best athlete in the family,” Bill Congleton said. Conky, as he’s become known around Huntington, was a teammate of Hal’s at Douglass, Huntington’s former allBlack high school. Later Conky would rise to prominence in the African-American community as president of the Huntington branch of the NAACP.

“If the color lines had been down when J.D. was in his prime, there’s no doubt in my mind he’d have been an All American in football or basketball. He’d have made All Pro too. As it was he did play with the Philadelphia Eagles for a while and the Denver Broncos ’til he busted a leg.”

The news that Marshall had signed its first “Negro” caused no great outcry in Huntington. Neither was it given great gobs of space in the local newspapers. That isn’t to infer that there wasn’t some grumbling. There was, but it was minimal. Replace it instead with a kind of watchful uneasiness that a way of life was about to end.

Naturally, the pressure on the skinny youngster was enormous despite the deliberately casual treatment he’d been given in the Huntington newspapers. In deference to Harold and his family they treated his signing by Marshall as just another promising ballplayer, not as Marshall’s or West Virginia’s version of Jackie Robinson in baseball.

“I remember going over to the playground with Harold when we were little kids,” Jim Venable said. Years later Venable, an outstanding scholastic athlete himself, would become a familiar fixture at Huntington’s downtown post office. “We’d try to get into a basketball game with the big guys but they’d shoo us off, wouldn’t let us in. They were afraid we’d get hurt. They were right. They were big. So we’d just go off and play somewhere else.”

Marshall’s first basketball practice that October of 1954 drew an unusually large crowd to the sagging old practice gym. All of the faces in the throng, which ringed the playing floor and the running track overhead, were white except two – Greer’s and Fred Austin’s, a janitor – and all eyes were riveted on Greer. Every time Hal whizzed towards the basket, skinny legs a blur, Henderson would smile. And the crowd would buzz. Every time Hal stopped and popped in that little jumper which would become his trademark, Henderson would smile and wink at a sportswriter standing next to him.

“Before that young man is through here,” Cam Henderson predicted that October afternoon, “he’ll become one of the greatest players in Marshall history and one of the greatest in the country.”

I know Cam said it. He said it to me. Ironically, Hal never played for Cam. Legend or not, Cam would be gone as Marshall’s coach by season’s end and the honor of coaching Greer would go to Jule Rivlin, Cam’s greatest pupil, his first consensus All American and the man who would be responsible for Greer’s being drafted into the National Basketball Association by the Syracuse Nationals – today’s Philadelphia 76ers.

Greer played three splendid seasons for Rivlin at Marshall. He finished with 1,377 points and a 19.4 scoring average in only 71 games – far short of today’s elongated schedules. The first and last games would be the most memorable of his MU career. The former was against Spring Hill of Alabama when Hal scored 20 points in his debut. The latter, against Miami of Ohio, resulted in a smashing 90-79 victory. It was a perfect sendoff for Hal. When he trotted off the court for the last time in a Marshall livery he fell into Riv’s arms. They locked in an emotional embrace as cameras clicked and the capacity crowd in Memorial Field House rose to give the player an incredible 10-minute ovation.

“That was one of the few times I remember Hal showing his emotions,” Jack Freeman, his hometown teammate, said. “He usually kept his feelings to himself. I guess he figured he had to. Still, he was well-liked on the campus. Lots of people went out of their way to be nice to him. But as far as I know, he didn’t date anyone. And he wasn’t close to anyone. Besides, he was too concerned with fulfilling his life’s ambition which was to play professional basketball. He sure fulfilled it.

“Hal kept to himself on our road trips too. After the games most of us would go out. Coach Rivlin didn’t keep a close check on us. But Hal wouldn’t go. He’d just stay in his room. He probably didn’t want to get into any embarrassing situations. Like the one in Charleston when we were there to play Morris Harvey. We went into a restaurant where we had reservations for our pre-game meal. The next thing we knew we were back on the street and Coach Rivlin looked upset. Nothing was said. Nothing was brought up. And there wasn’t much written about it. We were just kids. We didn’t realize what was going on, although Hal did. Later we learned the restaurant wouldn’t serve Negroes. They weren’t called Blacks or African Americans then.”

Freeman, longtime club pro at Bellefonte Country Club in Ashland, Ky., and Hal would have been teammates at Huntington High School if desegregation had been in effect. lronically, when they joined at Marshall they competed for the same shooting guard position. It was a fairly even battle until a sprained wrist took Freeman out of the running.

Hal saved his finest all around season for 1957-58, his last. He scored 567 points in 24 games for a 23.6 scoring average. Both were personal highs and placed him 17th in the nation. That was five notches below Leo Byrd’s 704. Hal was also the nation’s fifth best sharpshooter with a stunning 54.6 field goal percentage – many of his points came on his patented 10- to 15-foot jumper that he also used in his free-throw shooting where his 83.3 percentage was No. 14 in the nation. These were the credentials that earned Hal consensus All American honors behind such illustrious first team picks as Jerry West, Oscar Robertson and Wilt Chamberlain.

Rivlin, a former pro playing coach in the pre-NBA era, was convinced that his star pupil had all the tools to be a successful pro himself.

“I called Paul Seymour, the Syracuse coach, and told him to draft Hal as soon as he could,” Rivlin said. “Paul had played for me on the Toledo Jeeps in the old National Basketball League (Editor’s Note: the NBL was the forerunner of the NBA). I knew that he trusted my judgment. Well, Paul let it all hang out. He said he didn’t need any back court players. He said he had two solid back court guys in Larry Costello and Al Bianchi. He asked me if l knew of any 6’8″ or 6’9″ guys to play forward. I told him I didn’t know any who could play in the NBA but if he wanted a 6’2″ 175 pound guard who could run and shoot like crazy, I had just the man. Paul asked me who he was and I told him. I said Hal wouldn’t make his club in September but that he’d have it made by January. And once he had it made, no one would ever get him out of the lineup. But he wanted to know why January. I told him it would take Hal that long to learn to play man-for-man, that we had to play a zone here at Marshall because we were so small. ‘Riv,’ Seymour asks me, ‘are you sure about this kid?’ ‘Paul,’ I says to him, ‘after all our years together you ask me a question like that?’ ‘OK Riv,’ he says, ‘I’ll pick him No. 2 if he’s still available and I’ll give him until January to make the club. ‘He’ll be available in the second round,’ I told Paul, ‘because nobody knows him like I do. And he’ll make your club in January.”‘ Both of Rivlin’s prophesies were true. Hurryin’ Hal was still available in the second round, Seymour drafted him, taught him to play man-for-man defense, and by January he “made” the club. As the team’s No. 3 guard he averaged 23 minutes a game. In his first NBA game on October 19, 1958, he sank both of his foul shots for two points. This was his turning point, his one-way ticket to enshrinement at Springfield. To get there he played 15 seasons in the NBA, all with the same franchise.

He still ranks in the Top 20 on the NBA’s all-time scoring list, with 21,586 points. He was the sixth man in league history to score more than 20,000 points. He wears the 1967 NBA championship ring on his finger and in 1968 he was voted the most valuable player in the All Star Game.

And, let’s not forget, he has a street named after him in Huntington.

“I enjoyed my Marshall years,” Hal Greer said many years ago. “I never had any problems there. The worst thing was that incident in Charleston. We were checking into a hotel to take an afternoon nap and the clerk wouldn’t let me register. Coach Rivlin told the guy that if he didn’t let me register he’d call the governor, he’d call the newspapers, he’d tell everyone. Then he said to me, ‘Greer! Go upstairs!’ I did. I had a good nap too!”

Next Issue: Ernie chronicles the career of Jackie Hunt, the greatest all-around athlete in Marshall University history.

The Hal Greer File

Born June 26, 1936, Huntington, W. Va.

Height: 6’2″. Weight: 172 pounds.

No. 15 Marshall scorer, with 1,377 points.

No. 7 Marshall rebounding, with 765.

Fifteen seasons with Syracuse-Philadelphia.

NBA career scoring: 21,586 points (19.2 avg)

NBA Playoff scoring: 1,876 points (20.4avg)

NBA All Star scoring: 120 points

All-NBA second team. 1963 through 1969.

NBA All-Star Game record for most points in one quarter, 19 in 1968.

1958 – Drafted second round by Syracuse

1968 – NBA All-Star Game Most Valuable Player

1979 – Marshall University Hall of Fame

1981- James E. Naismith Hall of Fame