A case of unrequited love and jealousy in 1892 prompted Cabell County’s only legal execution.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 18 | SUMMER 1994

Ritter Park, Huntington’s beautiful municipal park, is 71 or so acres of trees, picnic areas and open spaces in addition to a creek, tennis courts, a jogging path, an amphitheater, a playground and a renowned rose garden. Almost daily, hundreds of visitors flock to the park to make use of its attractions while thousands of cars cruise along 13th Avenue and other streets bordering the park’s “front lawn.”

However, a century ago this was desolate, undeveloped land covered with brush, weeds and scrub trees on the outskirts of town. It was during this early period that Ritter Park was involved in a mystery of sorts: Did a public hanging witnessed by thousands of spectators take place in the early 1890s on what are now park grounds?

Several years ago, while doing research at the Marshall University library, I came across a reference card with the notation: “Hanging in Ritter Park.” The card led me to a 1978 taperecorded interview with an elderly Huntington man who gave a secondhand account of an execution by hanging of a convicted murderer named Allen Harrison, as it was told to him by his father who had been at the event. He claimed that the hanging had taken place in what now is Ritter Park. This statement was corroborated by the author of a book of local history who gave the date of the hanging as “Nov. 22, 1892.”

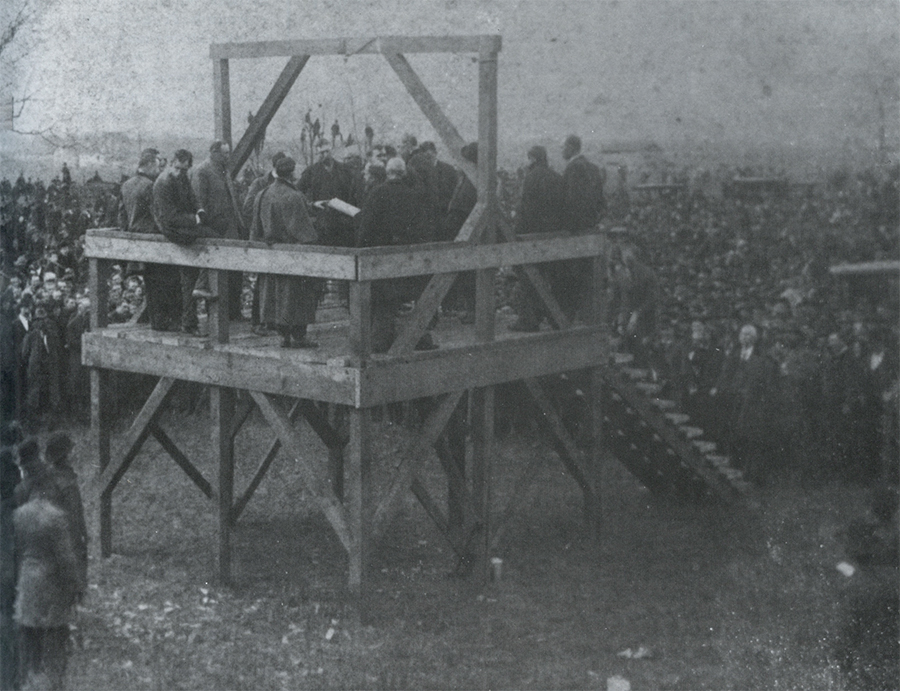

Armed with the condemned man’s name and the date of the execution, I searched through law books at the Cabell County Courthouse for records of the trial, the conviction and death sentence. Later, I heard about the existence of two photographs of the hanging. The photos, taken by a professional photographer at a medium distance, bear only the date: “Nov. 22, 1892.” The stark images in the old photographs reveal the faces, the businesslike clothes and derby hats, and even some of the reactions of those who participated in this little-known event in Huntington’s early history.

The public execution of Allen Harrison came as the final chapter in the aftermath of a brutal murder that was committed in northern Cabell County in the spring of 1892.

According to trial records, on a Saturday in early April 1892, Harrison, age 26, who had left his home after an argument with his father and was taken in by the Frank Adams family, murdered Adams’ 15-year-old daughter, Bettie. The motive was described as “unrequited love and jealousy.”

According to one account, Harrison worked part-time in the timber industry then in operation in that part of the county.

Trial records state that Harrison had lived in the Adams home for nearly a year and had fallen in love with Bettie became very jealous, especially when her boyfriend came around, and he and Bettie had frequent quarrels.

Trial records continue that on a Friday night, Harrison stayed at a neighbor’s house where he stole a pistol that was kept in a drawer. The next day, he bought rounds of ammunition at a nearby store. He also bought two 2-ounce vials of laudanum, a narcotic drug made of a mixture of opium in a solution of alcohol. He returned to the Adams house and, at the back door, he asked Bettie for a drink of water. He then walked into the living room and Bettie followed him into the room to take the ashes out of the fireplace. Almost immediately, Mrs. Adams heard a gunshot and her daughter yell: “Oh Ma, Allen has shot me!” She ran to Bettie and took her in her arms where she died.

Mrs. Adams found her daughter’s murderer in the room, pistol in hand, trying to shoot it again, but it was an old weapon and didn’t fire, trial records state.

Bettie’s younger sister later told authorities that she saw Harrison shoot Bettie in the back at point-blank range.

The records continue that Harrison fled the Adams home and went into the nearby woods. The Cabell County sheriff was notified of the murder and, a few hours later, Harrison was apprehended lying on the ground with a coat under his head. He readily admitted his crime and wanted the officers to take an axe and kill him then and there. He told them that he shot Bettie in the heart as she rose from taking up ashes and, as she turned, he shot her again in the back. He expressed no remorse and said that, if he was again given the opportunity, he would repeat his terrible deed.

On the way to jail in Huntington, Harrison unloosened the rope with which he was bound and tried to escape but was quickly recaptured. Either before or after the murder, Harrison took a large quantity of laudanum which made him vomit, trial records state.

In a 1978 oral history account on file at the Marshall University library, Mr. T.R. Riffle, then age 78, recalled the long-ago murder case for an interviewer. Mr. Riffle was a retired Huntington police officer who had lived most of his life in Guyandotte. He did not personally witness the crime or the execution but his father was at the hanging and had told him in vivid detail about what transpired during those events.

According to Riffle, Sheriff Ed Kyle arrested Harrison for the murder. Riffle adds that Kyle owned a house in that part of Cabell County and knew both Harrison and his victim.

Sheriff Kyle and a deputy transported Harrison in a horse and buggy to Huntington, where he was incarcerated in the county jail. “That is where the county jail and city hall both were,” said Riffle. A local history explains that during this time the county shared the use of the city building and jail which were then located on the east side of Ninth Street between 4 1/2 Alley and Fifth Avenue.

Records of the Cabell County Circuit Court reveal that on April 6, 1892, Harrison was indicted for a felony to which he pied “not guilty.” On April 11 and 12, a jury of six men was selected and sworn in. At the trial, more than a dozen witnesses were called on Harrison’s behalf, but to no avail. His only defense was an insanity plea. On April 13, the jury returned a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree without a recommendation of mercy, which meant that the death penalty was mandatory. The following day, the convicted man was sentenced by Judge Thomas H. Harvey as follows: “Do on Friday, the first day of July 1892, take this said prisoner, Allen Harrison, and hang him by the neck until he is dead.” The prisoner was returned to jail.

Harrison’s conviction and sentence were appealed to the West Virginia Supreme Court. On Oct. 8, 1892, a copy of the decision of the high court upholding the conviction and sentence was received by the circuit court. In their lengthy decision, the judges called the crime “a ruthless and cruel murder of a child a little over 15 years of age.” There was no evidence to sustain a plea of insanity, said the judges, adding “(Harrison) deliberately and secretly prepared the pistol hours before the bloody and cruel deed.”

On Oct. 13, the case was returned to the lower court to fix a new date for the execution. Judge Harvey ordered that “the sheriff of the county do on Tuesday, Nov. 22, 1892, convey the prisoner, Allen Harrison, to some convenient place in this county and there hang him by the neck until he is dead.”

There are several versions of where the gallows were located. In his account, T.R. Riffle says: “You know where the pine trees are at the entrance to (Ritter) Park on the east side? Now that is where the scaffold was built.”

George S. Wallace in his 1935 Cabell County Annals and Families states: “Harrison was hanged in what is now Ritter Park on Nov. 22, 1892.”

Wallace adds that this is the only legal execution that ever took place in Cabell County.

Another historical record, “Chronicles of Early Huntington 1871-1896” by Robert Archer, which was published in a 1946 or ’47 edition of the Huntington Advertiser, states: “The execution by hanging of Allen Harrison took place in an open field near the present site of Huntington High School.”

During Huntington’s early years, Eighth Street, which goes past the high school and Ritter Park, was the main route leading south out of town and going over the hills to Wayne. Archer’s chronicles relate that during this time “Eighth Street Road had corn fields on both sides.”

The public hanging of Allen Harrison was a sensational event, attracting thousands of spectators from Cabell County and surrounding parts of West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky. The photographs reveal that people stood in tightly-packed crowds around the scaffold and even in trees to watch the execution. Huntington’s position as the county seat and a railroad hub probably accounted for the large turnout.

At the time, Huntington was a city with 10,000 residents and several daily newspapers. Unfortunately, microfilm of Huntington papers for this period does not exist and the original editions are missing and presumed lost or destroyed. After an exhaustive search for accounts of the hanging in Tri-State newspapers, I received from the Cincinnati Public Library’s History Department copies of microfilm of Cincinnati newspapers containing the story of the crime and execution.

The headlines of the Cincinnati Enquirer of Nov. 23, 1892 blared: “Summoned Before the Courts Above to Answer for his Fiendish Deed. Allen Harrison Hanged in an Open Field for Murdering the Girl Who Refused His Love. The Execution in Many Respects a Very Remarkable One -Met Death Bravely.”

With a dateline of “Huntington, W.Va., Nov. 22, 1892,” the account continues:

“Ten thousand people assembled from all sections of southern Ohio and West Virginia saw the first legal execution that ever occurred in Cabell County today.

“Allen Harrison was taken from the county jail at 1:45 p.m. by Sheriff Kyle and driven through crowded streets to an open field on the banks of Four Pole Creek, and at 2:16, without the use of the black cap or any head covering, (Kyle) adjusted the noose and, after a brief prayer by Rev. Woods, he sprang the trap that sent the murderer of Bettie Adams into eternity. The drop was three-and-a-half feet, the physicians pronouncing Harrison dead in exactly fifteen minutes.

“At 11 o’clock today, the condemned man made a final statement to an Enquirer reporter in the presence of his attorney, J.S. Marcum, in which he reiterated his previous declaration that he did not know when he killed Bettie Adams. He acknowledged that he had been criminally intimate with his victim, and that her mother had come upon them at one time when they were in the same apartment. This discovery, and the fact that he was unable to support a wife, so preyed upon his mind that he determined to end his own life, but he had no intention to injure the girl. It was expected that Harrison would weaken at the last moment, but he was wonderfully composed on the scaffold, the result of alcoholic stimulants.

“The crime for which Harrison paid the death penalty was particularly sensational and, at the time of its commission, excited the people of Cabell County to a high degree. On April 2, 1892, Harrison drank a quantity of laudanum at his home near Ona … and arming himself with a revolver, he went to the home of Miss Bettie Adams, nearby, and when she was bending over the kitchen in the act of starting a fire, he shot her. After she had fallen to the floor, fatally wounded and dying, the murderer made assurance of her death by firing into her body another shot. He then went home and laid down to die from the effect of the drug he had swallowed. But the poison had weakened with age and when found a little later by excited neighbors he was only in a slight stupor, from which he soon rallied.

“Bettie Adams was 17 years of age and a daughter of Mr. & Mrs. Frank Adams, prosperous Cabell County people. Harrison had become infatuated with the girl. She was pretty and the beaux of the neighborhood were smitten. Harrison was persistent and so faithful in his attentions that he disgusted Bettie, and she repelled his advances. He became desperately persistent, and when she flatly refused to have anything to do with him he became crazed with rage and a desire for revenge, which resulted in the murder.

“The next term of circuit court, Judge Harvey presiding, tried Harrison for murder. His defense made a strong plea of emotional insanity, but the jury rendered a verdict of guilty in the first degree, and Harrison was sentenced to be hanged in August. The (W.Va.) Supreme Court granted a writ of error to hear arguments for a new trial. The court of last resort in September rendered the final verdict in the case, refusing a new trial, and Judge Harvey immediately called a special session of the circuit court and resentenced Harrison to be hanged today, the 22nd.

“Harrison’s two sisters, aided by the Sheriff and his attorneys, made a great effort to secure the commutation of his sentence to imprisonment for life. The petition was presented to Gov. (A.B.) Fleming on Tuesday, the 15th and after due consideration, he declined to interfere. The sentiment of the majority was against the hanging, the belief being prevalent that he was demented at the time of the commission of the crime.”

Another account was published in the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette of Nov. 23, 1892, under the headlines: “Betty Adams Avenged. Allan Harrison Executed Before a Great Crowd at Huntington, W.Va.”

This newspaper’s story reports that Betty Adams lived at “Ona Station, ten miles above Huntington. On the afternoon of Saturday, April 2, Harrison purchased a bottle of laudanum … appearing at the Adams house, and entering the kitchen, found Betty Adams kindling a fire with which to cook supper. Without any quarrel, or even words, so far as the evidence goes, he drew a revolver from his pocket and fired it at the girl. She fell to the floor, with a slight scream, and while her life blood was ebbing from a wound in her left side … the murderer was coolly watching her, to note if his shot had taken fatal effect.” Harrison was later apprehended “in a stupor from the apparent effect of a powerful drug,” the newspaper account says.

After Harrison’s Supreme Court appeal was rejected in October, he was resentenced to be executed Nov. 22.

The Cincinnati newspaper continues: “Since that time (October) the attorneys of the condemned man, Sheriff Kyle, Jailer Jones, the sisters of the condemned man and a large number of influential citizens joined in an appeal to Gov. Fleming for a commutation of the sentence to life imprisonment in the penitentiary. The petition was especially strong, (however) Gov. Fleming announced Wednesday (preceding the execution) that he could not interfere with the sentence of the Court, and that the law must take its course.”

The newspaper then printed a detailed description of the events of the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1892.

“At exactly 1:45 the procession left the jail and drove out Ninth (Street) to Seventh Avenue, then to Eighth Street, and then direct to the place of execution. At the scaffold there was a terrific jam, and the police and guards had a hard time keeping the crowd back and in a semblance of order.

“The party arrived at 2:16, and as the crowd swayed back to open up a gap, the condemned man was the first to alight from the carriage. He was followed by Sheriff Kyle and Jailer Jones … Following there came Rev. Woods. They ascended the scaffold in the order named. While Jailer Jones pinioned Harrison’s arms and legs, the Sheriff spoke some encouraging words to him, and he replied with thanks to those who had been his friends. Rev. Woods read the 51st Psalm, at the request of Allen Harrison, and then offered up a brief but very feeling prayer.

“The noose was adjusted by the Sheriff, no black cap being used, and while Jailer Jones stood behind the condemned, speaking a last farewell, the Sheriff calmly stepped to the trap lever and threw it back, and Harrison shot through into eternity. The drop was three feet six inches, and the knot of the noose caught just behind the right ear, forming a complete hangman’s knot.

“Drs. Row, Stump and Davis were at hand, Dr. Row holding the pulse and Stump the watch. In exactly fifteen minutes he was pronounced dead and cut down. Those present who had sufficient experience to be able to judge say it was a most successful hanging.

“The mother and father of Betty Adams were present and witnessed the execution inside the enclosure.”

The Nov. 30, 1892, Ceredo Advance, a weekly newspaper published in Ceredo, W.Va., also reported on the event: “Allen Harrison was hanged at 2:30 o’clock Tuesday evening. He spent a restless night eating scarcely anything … The death warrant was read at noon and an hour and a quarter later he was dressed in a fine suit of clothes and … was driven to the outskirts of town where a scaffold had been erected. Five thousand strangers witnessed the execution and came from Ohio, Kentucky and interior counties of West Virginia. The drop fell at 2:20 and at2 30 Harrison was pronounced dead by a corps of physicians. His sister, Mrs. Shy, took charge of the body and he will be buried tomorrow. Harrison’s father has left the family and his whereabouts are unknown.”

On that somber note of family dissolution, this grim chapter in Cabell County’s history came to an end.

Based on the accounts published in the Cincinnati newspapers, the location of the hanging can be placed as being on Eighth Street in “an open field on the banks of Four Pole Creek.”

The size of the crowd was estimated as high as 10,000 and as low as 5,000 people depending on which account you accept remembering that estimating crowd size is not an exact science.

In 1899, the West Virginia Legislature passed a law ordering all hangings to take place within the walls of the state penitentiary at Moundsville. West Virginia was one of the first states to prohibit public executions. More than 20 years after the hanging of Allen Harrison, the land on which the scaffold stood became part of Ritter Park, Huntington’s much-used and loved municipal park that was dedicated on Sept. 11, 1913.