When Huntington Made a Movie

By Deborah Novak & John Witek

HQ 19 | AUTUMN 1994

In the darkened shadows blanketing the dimly-lit stairwell underneath Huntington High School’s towering front steps, a young couple lingers in an embrace, but the teen-aged girl with the bouffant hairdo has more on her mind than romance.

“I’m getting more afraid every time I come to meet you here,” she confesses.

“Who’s ever going to find us here at school,” her boyfriend answers nonchalantly. “And anyway, where else can we go at night to be alone? Don’t worry.”

“I am worried, Jimmy. I’m afraid of something. I don’t know what it is.”

“Afraid? Of whom? Your folks’ll never know as long as they think you’re with Ann.”

As if on cue, her friend Ann steps into the dim light cast by a bare bulb overhead. “Betty, come on,” she exclaims in her southern drawl. “It’s late, I gotta go home. Betty, will you … “

“Okay, I’ll be right there,” she answers. Then, after a hurried goodnight to Jimmy, she turns to Ann. “I’m sorry.”

Suddenly, the school janitor appears. “Oh! Hello Mr. Wilson. What are you doing here? It’s so late,” Betty exclaims, unnerved by the man’s presence.

“I might ask you the same question, young lady. You shouldn’t be out this time of night – or any time at night when the school is closed. I’ll walk you home. Wait right here.”

But the girls are anxious to sneak home and slip off in the dark before the man returns. Running home through Huntington’s Southside streets, foreboding music flowing in the background, the girls glance around nervously as the normally tranquil neighborhoods begin to appear almost ominous in the late-night hour.

“I’m beginning to wish we’d waited for Mr. Wilson,” Ann says fearfully.

“It was your idea to leave.”

“Well, we did. Let’s go this way.” After they cut through a side street, Ann stops to catch her breath from the short run and is rebuked by Betty.

“Come on, Ann, we’ve got to go.”

“Oh Betty, I can’t. I’ve got to rest,” she says breathlessly. “Hey, did you hear something?”

“No, I didn’t hear anything. Look, I’m going. Come on,” Betty commands, as she runs ahead a few steps until she hears Ann’s bloodcurdling scream. Turning back to see the horrible tragedy she has just escaped, Betty cries out “No! No! No!” as she realizes her friend has become just another victim of … the Teen-Age Strangler!

One evening in 1964, Clark Davis, the manager of WHTN-TV, was sitting around the station previewing movies with five good friends. In the days before infomercials and home shopping, television stations bought “packages” of films to show in their late night time slots. On this particular evening, they examined what Davis describes as “the worst package” he’d ever seen. So the six businessmen looked at each other and said, “Hey, we could shoot our own movie cheaper and better than this.”

The group knew that the teen-theme movies of the day were big draws. There had already been “Teenage Crime Wave,” “Teenage Zombies,” “Teenagers From Outer Space,” even “TeenAge Cavemen” (with Robert Vaughn, no less), so a movie featuring a teen-age strangler, why not?

John Hamer, a local television personality, came up with the title, and Davis went home and wrote the screenplay and two songs in one night. From a passing remark, the film was well on its way to production and to inscribing itself in Huntington’s history.

“Teen-Age Strangler” is the story of al 964 serial killer, a “madman” or “thrill killer” as the movie suggests, and the terror he inflicts on the city. It is a small slice of classic Americana, complete with juke boxes, malt shops, drag strips and hot rods.

The movie may have been hindered by its low budget, but that in itself makes “Teen-Age Strangler” intriguing. The movie has all the elements of a silver screen blockbuster: romance, mystery, murder, chase scenes and even a sexy scene showing an attractive victim-to-be provocatively removing her nylons and blouse before stepping into the shower. While she was shown in nothing less than her slip, the scene was still risque for the times.

Though it was originally made as a shocker, in recent years “Strangler” has gained popularity for its nostalgic qualities. For retro buffs interested in low budget films of the ’50sand ’60s, “TeenAge Strangler” is a forgotten gem, filled with period characters, settings, clothing and hairdos.

“Thirty years later, it’s an interesting little movie to watch,” notes John Humphreys, one of the film’s stars. “It’s got ’60s clothes, ’60s hair, a rumble, and a drag race. It reminds us of the way we were.”

The film dwelled in the lonely obscurity of the drive-in circuit, and was even lost for a while, but it finally has achieved notoriety on the 30th anniversary of its production. In recent years it has been released on videocassette, shown at an Italian film festival, been the focus of a discussion on National Public Radio, and appeared before hundreds of thousands of people on Comedy Central’s Mystery Science Theatre, a popular channel carried by many cable companies across the country.

This is the story of the rise, fall, and rise again of Huntington’s own movie, “Teen-Age Strangler.”

“Strangler” was a low-budget venture from start to finish. The six businessmen – Clark Davis, Bob Schaub, Paul M. Brown, John Hamer, Lloyd Hamlin and Harold Banga – who formed Original VI Productions, raised $35,000 among themselves and other local business people. According to Schaub, even in 1964 this was “an astonishingly low figure,” considering the fact that the film was shot in 3 5 mm and in color to boot.

Because the Original VI had never produced a film before, they went looking for help. In New York City, they found an executive producer, who put together the production team. Ben Parker, the director, was a seasoned pro whose extensive credits included directing features for RKO, shorts for Paramount, Universal, Columbia, and prime time programs for the major television networks. Connie Pollard Griffith, who plays one of the strangler’s young female victims, remembers Parker as a “fatherly-type figure, who was very patient with amateurs.”

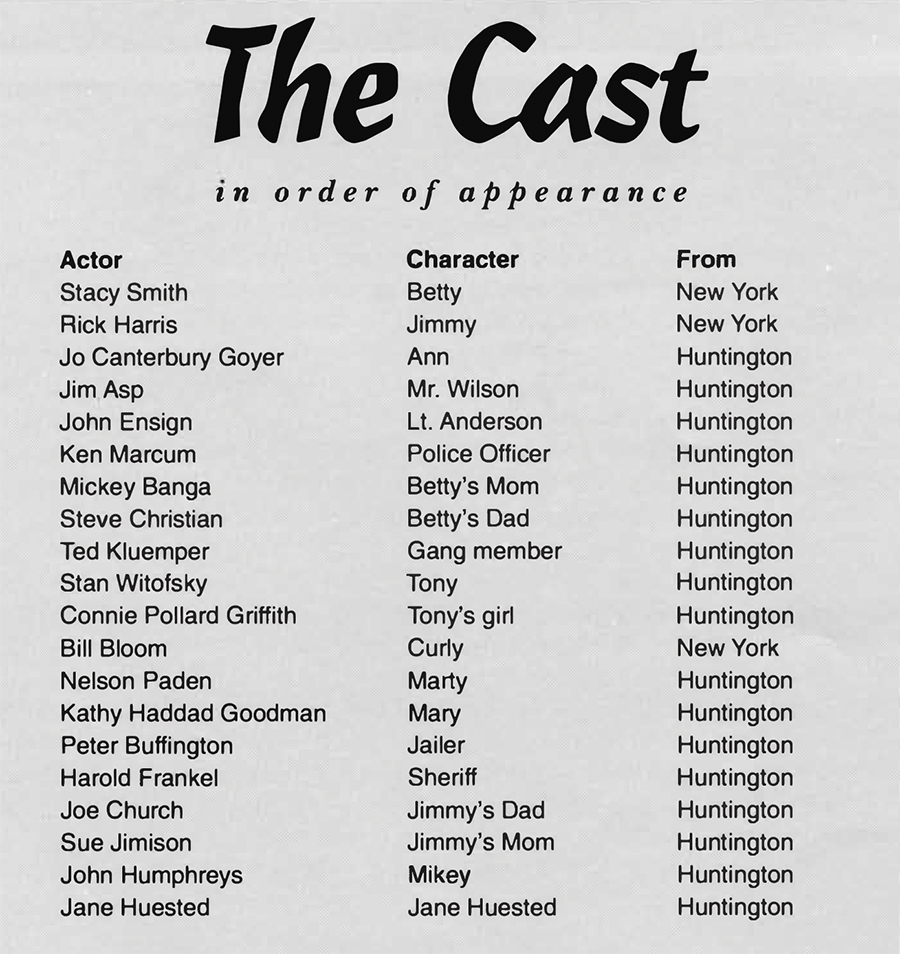

Though the three leading roles went to young actors from New York, Davis maintains that “Strangler” was a community effort. The vast majority of people who appear on screen are from Huntington, including a number of featured roles: John Ensign plays Lieutenant Anderson, the savvy police detective who attempts to solve a series of teen murders. John Humphreys plays nervous little Mikey, the kid brother of handsome Jimmy, who himself has been wrongfully accused of the crimes. Auditions for these and other roles were held at the Hotel Frederick, where local people with varying degrees of performance experience showed up.

Ted Kluemper, an insurance agent in Huntington, became involved in the production when he spotted an ad in the newspaper. Though he interviewed for a position as an extra, he was surprised to find himself chosen for a featured role as one of the “Fastbacks,” a high school gang described as the best in the state at drag racing.

“I was never in any plays before,” Kluemper says. “I don’t know how I got picked, but I did.”

In fact, Kluemper ended up with five speaking lines in nine different scenes. His big performance came early in the film when he was at the popular hangout and malt shop, Marty’s, with the other Fastbacks. When a student tells one of the other gang members to “shut up”, Kluemper’s character fires back, “Quiet runt, or I’ll stomp on ya!”

Jo Canterbury Goyer, a Vinson High School senior in 1964, had appeared in several local beauty pageants. For her audition as the first strangle victim, the director asked her to go behind a partition and let out a blood-curdling scream. She did, he said, “that’s fine,” and she got the part.

Kathy Haddad Goodman was an experienced performer who has appeared on the Marshall stage and in other community productions and studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York. In ’64, Goodman was doing summer stock when she heard about the film being shot in Huntington.

“At that time,” says Goodman, “I was so involved in show business, I was just thrilled at having the opportunity to do a film that I could add to my resume.”

“Strangler” was shot in a series of 14 long, grueling days. Humphreys remembers one scene at the Cabell County Jail that took 17 hours to complete.

“It was a very emotional scene,” he says, “and we kept doing it over and over again.”

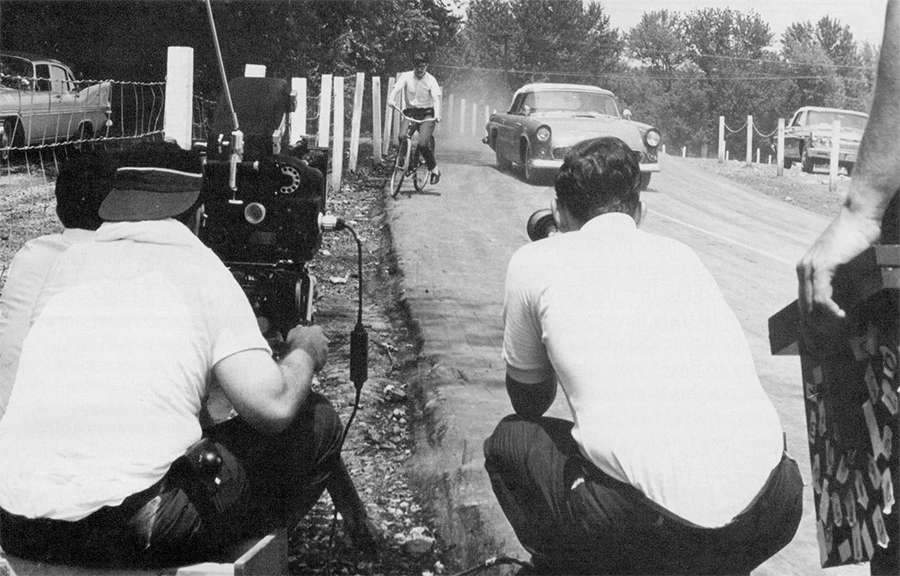

Likewise, when Mikey attempts to warn his big brother that the police are mistakenly after him, he gets knocked off his bicycle by a drag-racing teen-age bully.

“We didn’t have any stunt doubles,” Humphreys says. “We rehearsed that scene 12 times and then we did four takes. By the time we finished, I was cut and bruised and in such pain.”

But because the production was on a tight budget, most scenes were simply shot once. Peter Buffington, who plays the role of the Cabell County jailer, remembers that his scene with the Fastbacks was completed in just one take.

“I was surprised,” Buffington says, “I thought they would do more, but they didn’t.”

Most of the Huntington actors had appeared on stage before, but were not used to acting in front of a camera. Because films are shot in little bits and pieces, John Ensign, an experienced stage actor, remembers feeling “totally out of place” with the schedule.

“I felt at loose ends as to what I should be doing.” he says, “and I was lost as to how far to carry the emotion in each scene.”

Moreover, many of the experienced local actors were not used to the quick “off the cuff” nature of low-budget film acting.

Steve Christian, a graduate of the Yale School of Drama, was trained in developing a character in relation to the storyline. But because of the budget, he never saw a complete script and never knew the whole storyline until he saw the film. Instead, he rehearsed with a “side,” that had only his cues and lines written in it.

“The director told me not to worry about memorizing lines,” remembers Christian. “But I said, ‘Hey, I’ve got to rehearse this.’ So John Ensign and I ran a few lines and then they told us ‘we’ve got to do this now,’ and so we shot it with maybe only one or two re-takes at the most.”

Because of the film’s low budget, Huntington’s actors were asked to provide their own costumes, including Harold Frankel, the sheriff of Cabell County in 1964, who appeared in his own dress uniform, a snazzy white suit complete with brass buttons and epaulets. Playing himself, Frankel appears on a television set to broadcast a warning to the citizens of Huntington:

“Parents and teen-agers of Cabell County, last night a third child was victim of a dastardly crime. Somewhere in this city, a madman is preying on teen-aged girls. The police department and your sheriff’s office are doing their best to stop it. We urge you not to try to take the law into your own hands … stay home, stay safe!”

“Strangler” stayed within its tiny budget, but this could not have been accomplished without community support. According to Davis, “the whole city cooperated.” Locations, for example, were donated to the production. Harold and Dody Frankel offered the use of their ultra-modern home (now owned by Dr. and Mrs. Ralph Stevens) overlooking South Boulevard. Martin’s Restaurant, which was located beside WHTN at what is now Huntington’s Vanity Fair, was turned into “Marty’s,” a teen-age hang-out decorated with pennants from local schools such as Ceredo-Kenova, Milton and St. Joe. From beginning to end, the scenes are all Huntington, from shortcuts through southside backyards to the county jail to car chases over local brick streets. The only exception were scenes filmed at the Riverside Drag Strip in Chesapeake, Ohio.

Downtown merchants provided costumes and props in exchange for onscreen credit. Belle’s of Huntington donated the leading lady’s wardrobe, Galigher Ford provided trucks, while Schneider Funeral Home’s hearse appears in several scenes.

The film received special cooperation from the Huntington Police Department as well. Ken Marcum, who was an actual patrolman on the force at that time, appears in the film.

“They needed a policeman with a uniform,” Marcum says, “so I volunteered.” He also was instrumental in obtaining the use of a police cruiser for the chase scenes. And he remembers that the Fastbacks’ black leather jackets were borrowed from Huntington’s motorcycle patrol. For the film, police insignia were temporarily removed and replaced by the Fastbacks’ bulldog emblems which were simply glued on.

The police department also provided expertise. Nelson Paden, who was then a lieutenant on the force, became a technical adviser after he noticed a scene did not reflect proper police procedures. Paden remembers that in rehearsal a police officer entered a restaurant, took off his hat, and was overly polite in looking for a murder suspect. He informed the director that an officer would never take off his hat in that situation because he would want to keep his hands free. From then on, he became “Strangler’s” adviser on police affairs. In addition, Paden was cast in the role of Marty, owner of the restaurant where the kids hang out.

The film’s two songs “Yipes Stripes” and “Willows Wept,” were performed by Danny Dean and the Daredevils and recorded at WWHY, a radio station located in the Hotel Frederick. In one of the film’s most memorable moments, Kathy Goodman steps on top of the counter at Marty’s and announces to the group of teenagers:

“Fellow citizens and lovers of good music. For those of you who have pledged your allegiance to Peter, Paul and Mary, those of you who have undying love for the Beatles … The Teen Queens … Paul Anka … not to mention the Chad Mitchell Trio … l proudly introduce you to Mary and Jack – The Huntington Astronauts! We’re out of this world! And here is our newest record sensation, just released on an RCA Victor label – not a record, mind you – a label!”

Wearing a striped dress, she begins to sing “Yipes Stripes,” a song which capitalized on the prevailing fashion trend for pin-striped shirts and fruitstriped gum:

“I had a fellow who told me

Nothing I wore seemed to fit.

I let the new fashions enfold me

My sweetie told me this is it.

Yipes Stripes!

That’s the latest fashion.

Yipes Stripes!

That’s the thing to wear …. “

Though the song and its unmistakable early ’60s beat has little relation to the plot, it’s a show-stopping number that’s one of the film’s high points and sends the kids at Marty’s dancing in the aisles. Of particular interest in this scene is the character Tony, played by Stan “Crazy Legs” Witofsky, who really cuts a rug doing “The Chicken,” a popular dance of the day.

Like any production, “Teen-Age Strangler” had its share of problems. Money was a constant worry and often forced the director, Ben Parker, to improvise on the set. According to Humphreys, Parker needed three attractive girls to appear in the background of a high school shot, so he spotted three girls coming back from the Ritter Park tennis courts and gave them $5 to be in the scene.

Budget constraints also forced Parker to cut and rewrite the script. In the original version, poetic justice prevails. The fleeing strangler escapes to the roof of Huntington High, gets tangled in the lines to the flag pole, slips off a ledge, and a la Bill Sykes in “Oliver Twist,” is himself strangled. In the economical version actually filmed, Lieutenant Anderson carefully breaks a single window pane at the school and shoots the villain. The prospect of breaking a school window ruffled a few feathers with the Board of Education, but eventually permission was obtained and the rewritten scene was shot on schedule.

In the end, however, many were disappointed with the results. Davis became angry with Parker because he felt “he had no feel for a teen-age movie.” Local actors, such as Humphreys, who had no previous film experience, were disappointed because they felt they overacted for the camera.

Steve Christian calls the film “appallingly poor. I attribute any shortfalls,” he says, “to the fact that this was a low budget film, shot on a 14-day schedule, with little or no re-takes. The first time I saw it I said, ‘Burn it!”‘ laughs Christian.

Summing up the disappointment, producer Schaub says that the final version of the film “was not nearly what we wanted.”

In addition, a costly error disqualified “Teen-Age Strangler” from being sold to television as was originally planned. After each day’s shooting, the “rushes” were flown to New York by Nelson Paden, who was a commercial pilot. He would wait for the film to be developed and would fly it back home in the same day. According to Davis, an anonymous person who was responsible for getting the film to Paden lost one day’s shooting on the way to the airport. In the final edit, “Strangler” came up six minutes short and was unable to be sold to television.

After several attempts to option the film failed, Herschel Gordon Lewis, a producer of many Saturday night shockers, took over the distribution of “Strangler” and began to show it in drive-ins throughout the south and midwest. Distributed by Lewis, the actual premier of “Teen-Age Strangler” probably occurred in 1967 in Atlanta when it was double-billed with Lewis’ own “A Taste of Blood.” Plans for a Huntington debut never materialized.

“We were promised spotlights and limousines,” Humphreys says, “but it never happened.”

In 1967, Humphreys drove to Cincinnati to see his debut on the silver screen at a drive-in. The movie was part of a triple-bill that also included “A Taste of Blood” and “Castle of Blood.”

“It was mortifying,” Humphreys recalls. “I sat through the other two films and they were really bad, too. I went to the concession stand and was actually afraid someone might recognize me.”

In 1968, other cast members from Huntington finally saw themselves on the silver screen at the Tri-State DriveIn in Chesapeake, Ohio.

But the Original VI producers eventually lost track of their film, and no more was heard about “Strangler” until the late 1980s when it resurfaced on videocassette. According to Schaub, the producers have “no idea how it got to the video company.”

Mike Vraney, the owner of “Something Weird Video” in Seattle, Wash., which distributes “Strangler” on cassette, said that the rights were acquired from a film lab and he dubs his videos from a rare original negative. How and why the film was left at the lab is a mystery.

Vraney considers the film “a rare piece of regional Americana,” and Psychotronic Video magazine has proclaimed “Strangler” to be “a marvel.”

Steve Fesenmaier, West Virginia’s Film Library Commissioner, has called it a “masterpiece.” Clips have appeared in a Barq’s Rootbeer commercial on MTV and in addition to showing the entire film, Comedy Central’s Mystery Science Theatre regularly begins their program with a shot of Humphreys as nerdy Mikey, the kid brother.

According to Mary Jo Pehl at Comedy Central, “Strangler” has “a magical synthesis of the elements.” Pehl and her colleague Paul Chaplin say their program looks for ’50s and ’60s films that have a storyline, action, downplayed violence and were shot in color. “Strangler” met all of their criteria and was selected by MST from hundreds of other films of the period.

Aside from the nostalgic qualities, another draw of a cult classic like “TeenAge Strangler” is the sense of actuality that pervades it. Though its production values pale in comparison with a slick, Hollywood product, “psychotronic fans” celebrate the film’s rough edges and its down-home atmosphere.

“You see an earnest effort being made by the real people in this film,” Pehl says. “We do a lot of films here and that was one of my favorites.”

Thirty years after it was made, “Strangler” has found its audience at last. According to Paul M. Brown, one of the Original VI, what’s happened to the film is “beyond my fondest dreams.” Though it may not have turned out the way they wanted, all three surviving members of the production team still take pride in their venture because, as Davis notes, “we were determined to make a movie, and we did it.”

Whether you view “Teen-Age Strangler” as a homemade horror film or a retro gem, whether you see it as a slapdash production or a psychotronic masterpiece, one thing is certain: “Strangler” represents a dynamic community accomplishment. The final credits of the film acknowledge the true heroes of this effort – the citizens of Huntington, West Virginia, “without whose assistance this motion picture could not have been produced.”

Copies of “Teen-Age Strangler” may be obtained from:

West Virginia Public Libraries

or

Something Weird Video Department F.U.N.

P.O. Box 33664

Seattle, WA 98133

Phone: 206-361-3759