Remembering when Huntington was home to one of the most unique golf tournaments in America

By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 20 | WINTER 1995

Huntington is often pictured as a fading city, an urban relic locked into an ante-bellum mind-set with little or no tolerance for equitable ethnic and racial mixing.

It’s an unfair evaluation, as many from all persuasions believe, that overlooks the significant racial and ethnic advances Huntington has pioneered in politics, education, professions and certainly in sports. Pioneered them quietly, too, in several cases, deferring to the understated rather than overstated fanfare.

The Ebony Golf Classic was one of those breakthroughs. Generally overlooked and sadly unappreciated, it was, nonetheless, spectacularly significant as one of the nation’s first black sponsored and controlled, totally interracial, independent amateur tournaments. It was an annual event whose brave manifesto sought to mix friendly competition with pleasure for all races, and not make too much of a fuss about it.

Started in 1971 by a small group of Huntington African Americans, the brainchild of a future mayor – he would be the city and the state’s first black man in the office – each July it drew ordinary people, as well as golf celebrities, from an average of 20 states, the District of Columbia and even parts of Canada.

Then, to the dismay of these yearly visitors, the Ebony suffered a premature death. It was barely 17. But it didn’t die a failure. Quite the opposite. The Ebony simply outgrew itself financially. With no national sponsor, despite a lengthy search for one, it was victimized by its own successes, a $65,000-styled tournament grossing only $40,000.

Before that unhappy ending, however, and depending on one’s private convictions, the Ebony was many things to many people in its short, happy life. What was one person’s symbol for the brotherhood of man was another’s salve for a guilty conscience – and a third’s flirtation with miscegenation, given the uneven tenor of the times in which it first saw the light of day.

But if blessed with calm rationale, one must conclude, looking back now, that the Ebony wisely sought to be none of these. It pretended to be nothing more than the bearer of a simple, human message that it first delivered rather timidly, barely above a whisper, in 1971. Hardly anyone heard or noticed. Said former Huntington mayor Joe Williams, creator of the Ebony, “We felt then and we still do to this very day, that if you played golf in the Ebony the way it was meant to be played, and if you lived your life the same way, then you would have no problems that were insurmountable. On or off the golf course.”

Guided by that simple premise, the question must be asked: did the Ebony bring the races together in its short life, if only for a little while, to reveal themselves to each other as human beings enjoying each other’s company in the most human, most humbling of games, followed by a quiet dinner ance and muted socializing? The answer would be yes. The Ebony succeeded. Far beyond its wildest dreams.

If, however, it is also asked: did the Ebony advance the causes of social justice, or any of the other great social issues that continue to haunt us as a nation 125 years after the last slave ship landed, then the answers must be qualified yeas and nays. The Ebony did no preaching, you see. The Ebony enlisted in no social crusades. It only reminded us that we are all God’s children.

As such, the Ebony therefore invested $2,000 of its modest budget money each year in a broad spectrum of community and civic projects – the Huntington Jaycees, Special Olympics, YMCA Buddy Basketball, Fraternal Order of Police, Regional Golden Gloves, Scott-Taylor Community Center, Huntington Heart Association, Huntington NAACP’s adult and youth divisions, Harry Wood Memorial Scholarship Fund, Marshall Big Green Scholarship Foundation, various high school booster groups and youth tennis and golf clinics. Surely one of the tournament’s most unusual causes was the partial underwriting of the former Miss Debbie Barnett’s candidacy for Miss West Virginia Teen. Estimates are the contributions totaled close to $30,000!

“Let’s get together,” the Ebony’s policy declared, “and play the game the way it was meant to be played – for each other, together, side by side.”

Never, in more than a half century in sports journalism, have I observed a more poignant proposal, because the askers weren’t frenetic, though they were the chief sufferers of our divided social and civic houses. Since when did alms come from the poor, the oppressed and the misbegotten? Well, they came from the Ebony, right under our civic noses. And Huntington, the Tri-State and the United States were spiritually richer for it. Even if only for a little while.

Has there been a greater irony anywhere? By choosing golf, man’s original game for gentlemen of the nonworking class, the Ebony advised us in its 17-year run that life is filled with ironies, that unintended or not, various economic and social forces made – and have continued to make – golf the last outpost against the casual mixing of the races.

Yet golf was the instrument the Ebony’s founders deliberately chose to effect a change and it was also why its early years were so difficult.

Williams, now a highly successful businessman as an owner of Basic Supply Inc., remembers those years. Especially the first two Ebonys when the tournament – a one-day, 18-holer – was bounced from Forest Hills in Chesapeake to Sugarwood in Lavalette. Unattractive, throwaway playing dates and lukewarm support from the golfing public forewarned a short unhappy life for his brainchild. The first tournament, as yet unnamed, attracted – if that’s the correct word – 31 entrants. Things were even worse the second year – only 22 golfers showed up.

“We’d planned for 48 minimum,” Williams says. “Shirley [Mrs. Williams] and I had to dig into our savings for $400 to cover our losses. That came very close to being the end for us.”

By then the founders had given themselves a working name, The Ebony Golf Classic, a name inspired by the popular Ebonite bowling ball, and while it would leave little doubt about the tournament’s genes it may have been responsible for the drop-off in entries. “We were realists,” Williams says. “Whoever heard of a golf tournament, open to everyone and run by Blacks?”

The effete leaders in Huntington’s golf establishment either didn’t want to hear or they weren’t listening.

There then occurred, in early 1973, one of those strange twists of fate that palpitate romantic hearts. Patsy Jefferson, a born and bred segregationist who’d recently made a complete 180-degree turnaround from that nonsense, was told of the Ebony’s plight and its desperate search for a new home. When Doris Kelly, one of Jefferson’s most trusted black employees, filled him in on what was happening, Patsy, without batting an eye, offered the Ebony his own beautiful handmaiden overlooking the Ohio River, the Riviera Country Club. It was a marriage proposal that set many heads wagging over their tee shots.

Well, the marriage lasted and prospered beyond Jefferson’s death in 1979 and the ownership of Julian Neal until the finale in 1987. Entries more than doubled in the switch to the Riviera. That convinced the Ebony’s fathers to expand play to two days and to 36 holes in 1974. They also added a prize list and a handsome, revenue-enhancing program and – lo! – the field tripled to 156, then jumped to 201, continuing to grow and grow.

A women’s division was born in 1976, the same year that Lee Elder, the first Black to play in The Masters, became the Ebony’s first guest celebrity. Elder was a proper choice. He’d been hired the year before by the West Virginia Minorities Businessmen’s Association to survey the Riviera for possible purchase. Jefferson’s price was $500,000, a bargain at today’s rates that translate into $1.5 million. Nothing happened.

The Ebony added a third round in 1977 to become a full fledged, 54-hole Friday-through-Sunday stroke play event with all the social trimmings. In 1978, a pro-amateur division was introduced. Its prize money pot was $2,500, with $1,000 to the winner. Within three years the pot grew to $5,000 and the winner’s share to $2,000.

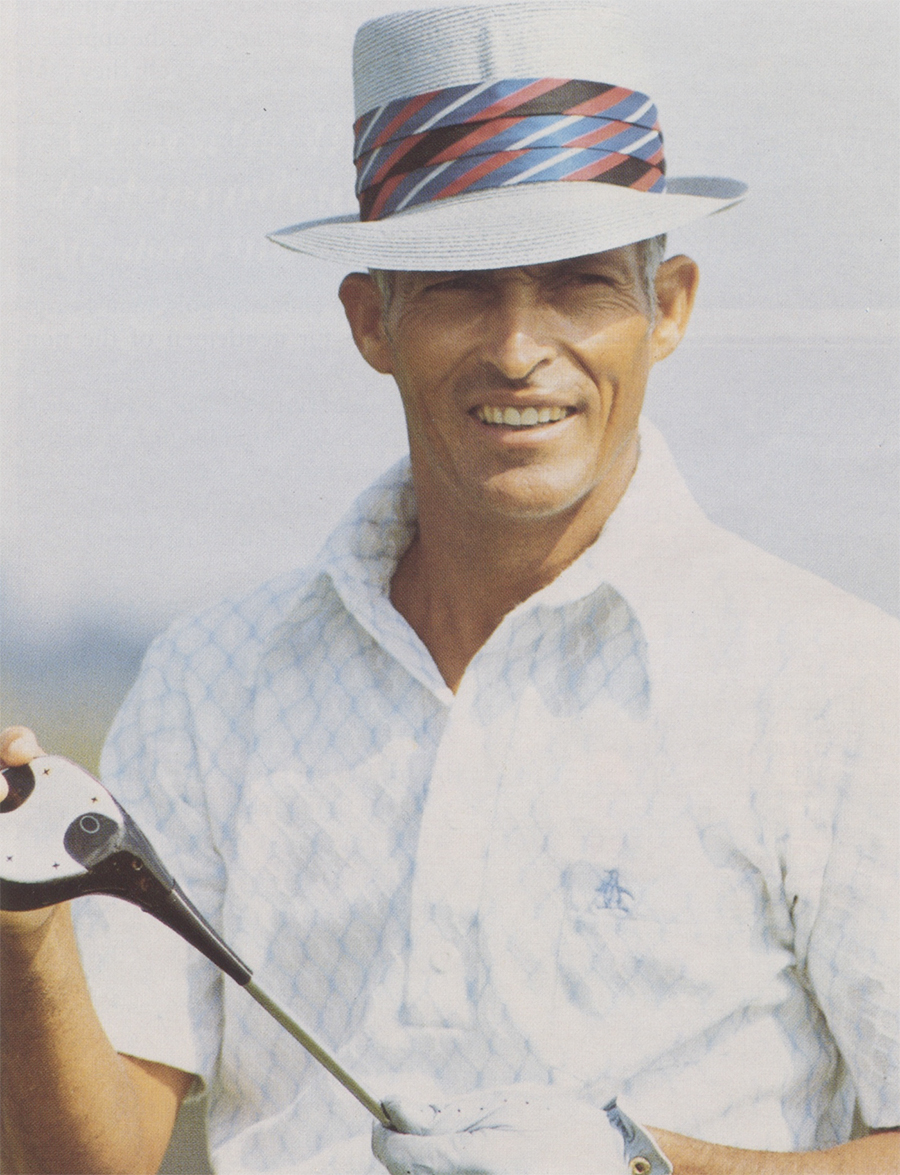

Colorful, ebullient Chi Chi Rodriguez, the workingman’s golfer, followed Elder as the second celebrity guest golfer to play the pro-am. As expected, both the fans and the contestants loved him. So Rodriguez returned for two more. He was low pro in 1979 and 1983. He might have made it three of three but a four-stroke penalty took him out of the running in 1982. He was carrying too many clubs in his bag. After his 1983 victory, Rodriguez magnanimously contributed his $2,000 winnings back to the Ebony’s causes. Long hitting Jim Dent, the first Black star of the PGA tour, and Barboursville native Barney Thompson, then a tour regular, rounded out the celebrity list.

A scramble replaced the pro-am in 1985. Subsequent honorees included Marshall’s own LPGA star, Tammie Green; BA and Marshall Hall-ofFamer Hal Greer; and Leo Byrd, also a Marshall basketball Hall of Famer. The Ebony rewarded Green upon her return, as a two time women’s division champion, with a green Marshall blazer she still takes everywhere she plays.

The Ebony Golf Classic has been gone eight years now. During its lifetime it drew close to 10,000 out-of-town and out-of-state visitors to Huntington. About half were golfers. In exchange for the roughly $225,000 they paid in entry fees over the years, dating to the 1973 switch to the Riviera, they spent an average of $65 apiece a day for three days, or roughly $110,000 to $120,000 a year. The Ebony, when it shut down, had become a still-growing $1.7 million community asset, give or take a few thousand. One major national sponsor would have saved it. But that was not to be. No sponsor was found. Having grown too large for the local community to support, it died.

Nevertheless, the Ebony’s ideal lives on, because as golfers hit and walk and moan and groan, squat and squint, pitch and putt, a common bond emerges, wiping out whatever differences, real or imagined, might have existed before tee-up. Birdies, pars and bogeys are no different from base hits or forehand volleys. They respect neither color nor religious preferences. They do encourage conversation.

When people talk to each other, as the Ebony proved hundreds of times each year for 17 years, they soon know each other and friendships or common interests are born.

“I guess in that sense,” Joe Williams says, “the Ebony will never die.”

Next issue: Ernie concludes his eight-part series with tales of his encounters with some of the greatest celebrities in sports.

The Ebony Golf Classic File

Men’s Division Champions

1971 – Carroll Plybon

1972 – Danny Borbach

1973 – Eddie Williams 1974- Bryan Beamer

1975 – Jim Ward

1976 – Jim Ward

1977 – Jim Ward

1978 – Jim Ward

1979 – Jim Ward

1980 – Jim Ward

1981 – Mike Owens

1982 – Ted Trice

1983 – Willie Miller

1984 – Evan Harbour

1985 – Evan Harbour

1986 – Pat Carter

1987 – Pat Carter

Women’s Division Champions

1976 – Catherine Payne

1977 – Nancy Bunton

1978 – Nancy Bunton

1979 – Nancy Bunton

1980 – Tammie Green

1981 – Charlotte McGinnis

1982 – Tammie Green

1983 – Sally Wallace

1984 – Peggy Freeman

1985 – Sally Wallace

1986 – Nancy Toothman Lewis

1987 – Peggy Freeman

Pro Amateur Division

1978 – Jack Ferenz

1979 – Chi Chi Rodriguez

1980 – David Smith

1981 – Keith Parker

1982 – Keith Parker, Ralph

Landrum, John Gagai

1983 – Chi Chi Rodriguez