The Story Behind the Monument and the Man

By Joseph Platania

HQ 22 | SUMMER/AUTUMN 1995

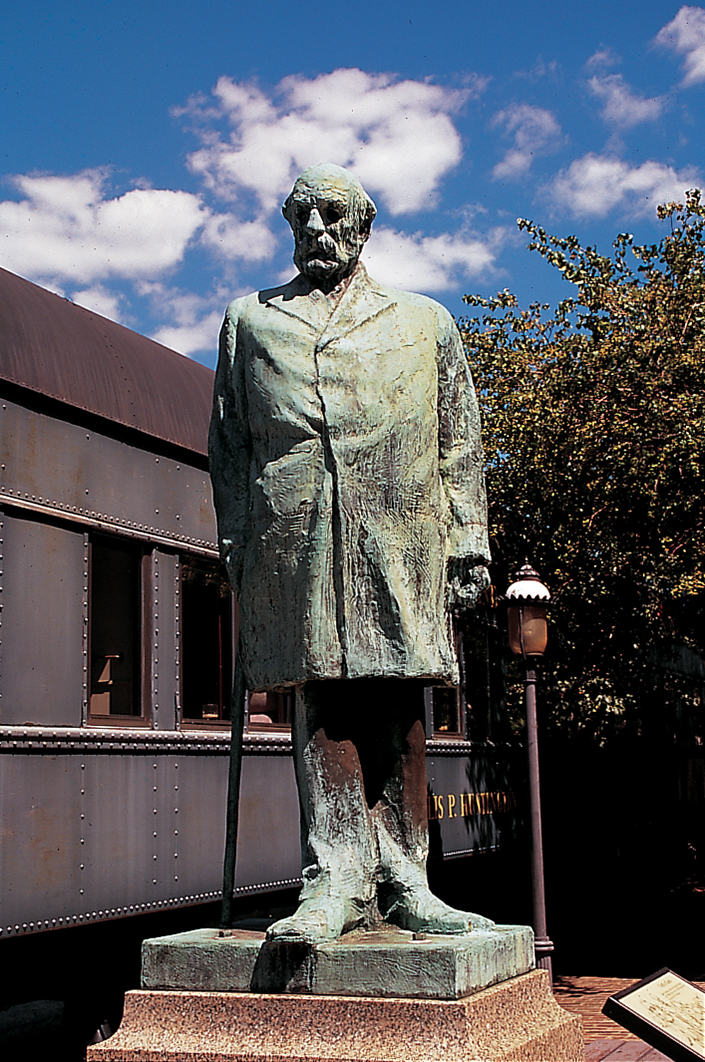

A visitor walking through Heritage Village in downtown soon comes upon the larger-than-life bronze statue of Collis P. Huntington installed atop its inscribed marble base. The statue possesses that weathered-with-age look as it stands watch over the historic site.

Nearby are a vintage steam locomotive, coal tender and refurbished Pullman car named “Collis P. Huntington.” However, Heritage Village is the statue’s second home.

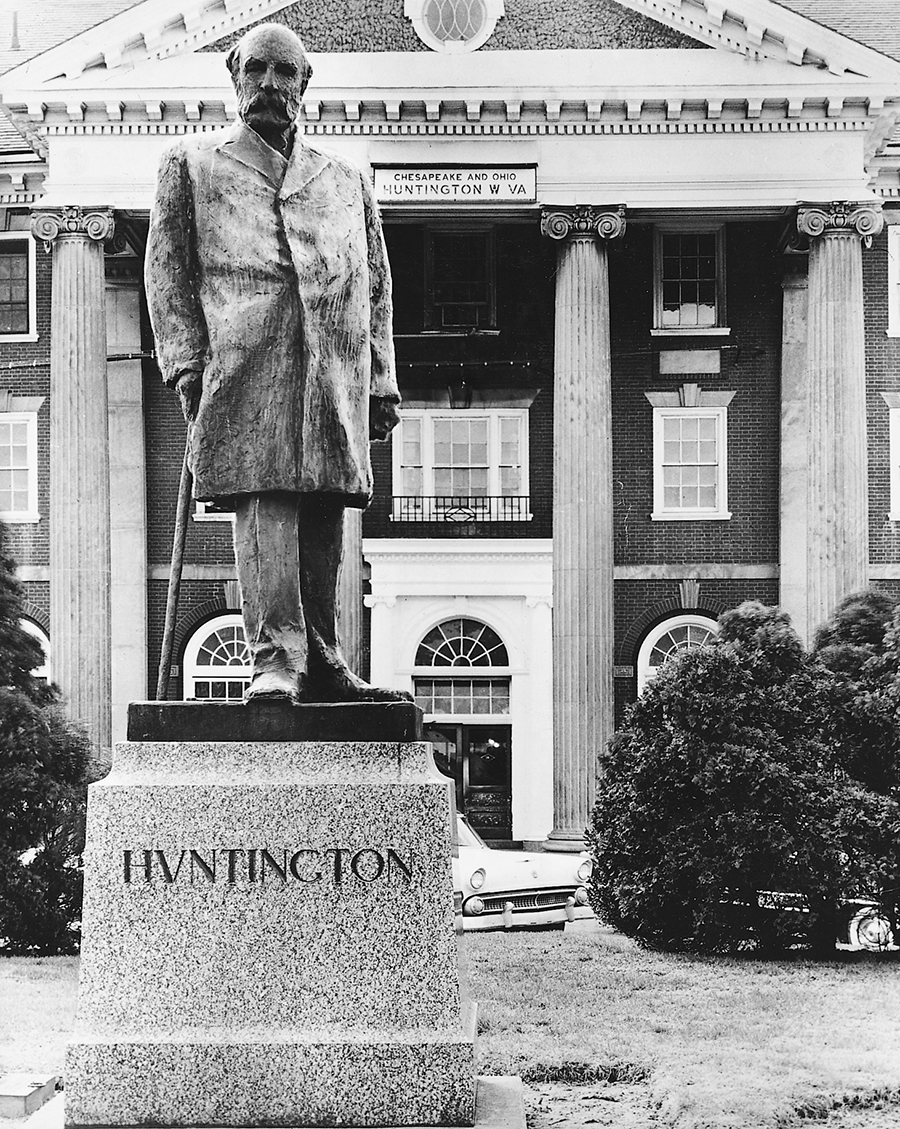

From October 1924 to May 1977, this representation of the city’s founder, wearing a long coat and clasping the head of a cane, stood on the plaza in front of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway’s midtown station and faced Seventh Avenue. From his vantage point, Collis Huntington looked out over his bustling namesake as both the city and the railroad grew and changed.

Many Huntingtonians who rode passenger trains during their glory days recall that seeing Collis P. Huntington let them know they were back home. In fact, for most of its time in front of the C&O station, the towering bronze became known as the unofficial symbol of the city of Huntington.

The relocation of the statue from its original site has sparked a controversy that has divided the community. Should Collis P. be returned to his original spot or remain where he now is located?

CSX Transportation, the successor to both the C&O and the B&O railroads, wants the statue returned from the Greater Huntington Park and Recreation District, which owns and operates Heritage Village, and placed in front of their newly remodeled CSX offices. The transportation con-glomerate might have a case since its depot was the site of the statue’s dedication on Oct. 23, 1924.

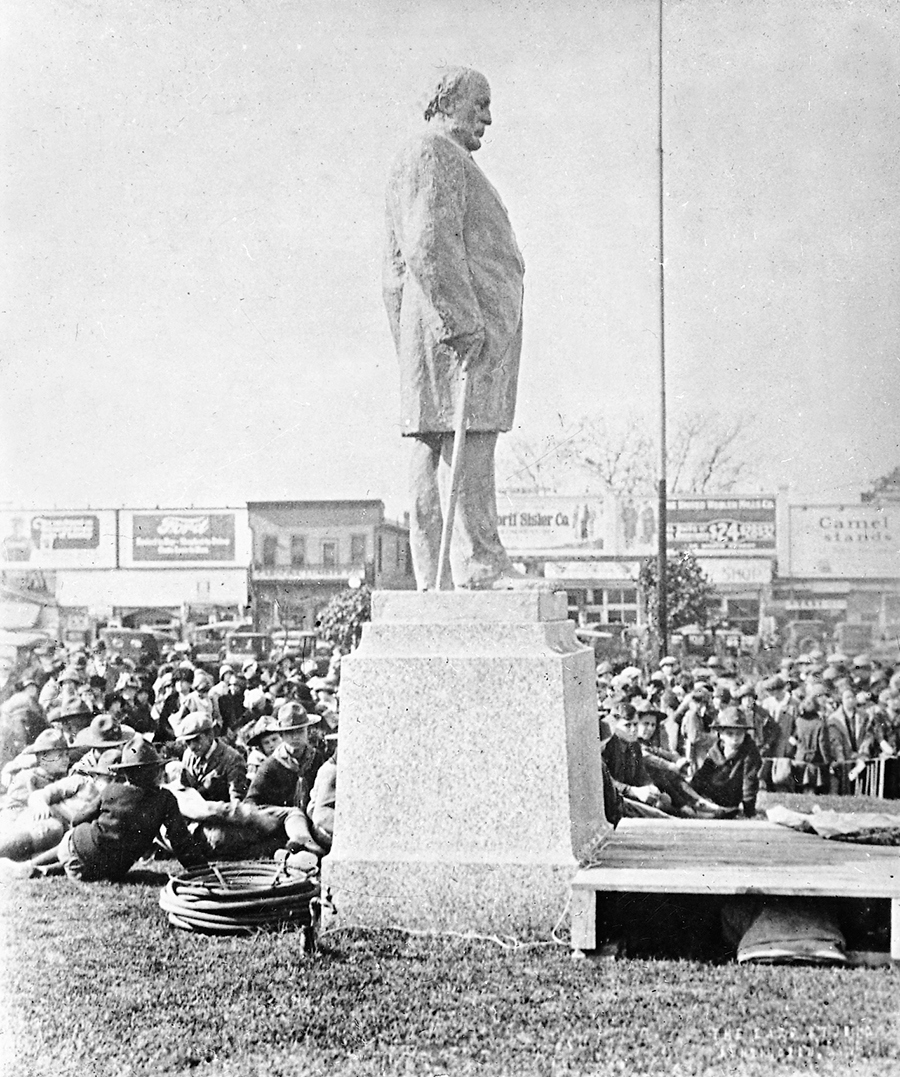

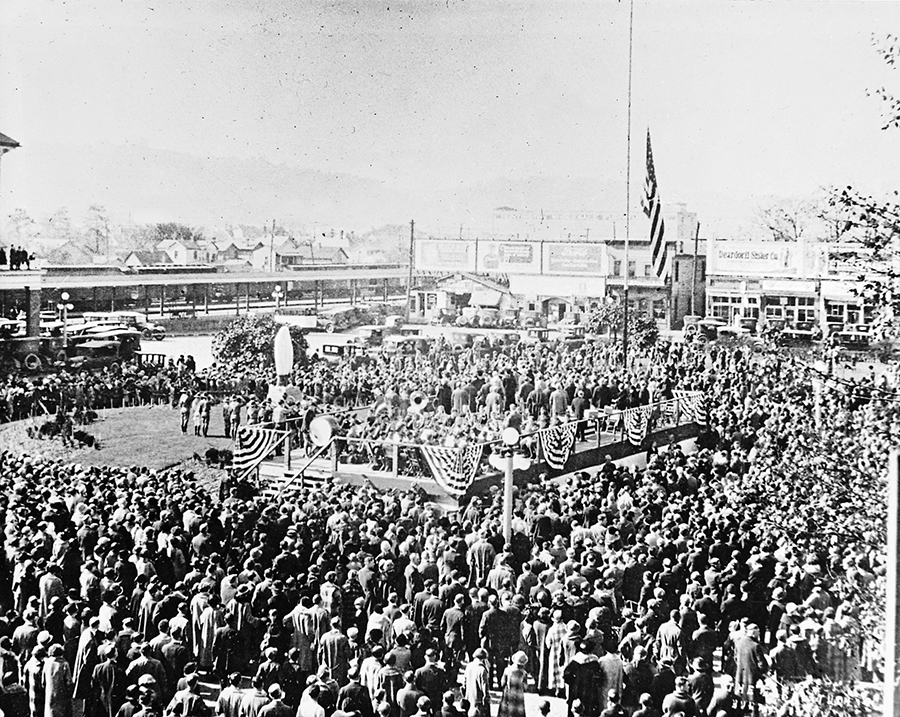

According to newspaper accounts, while a crowd of more than 7,000 looked on, the Huntington statue was unveiled and presented to the city and to the C&O Railway. The day was described as “Huntington Day” in thousands of souvenir programs printed and distributed by the chamber of commerce.

The newspaper reported: “The statue which immortalizes the man, who, after blazing a trail through the wilderness and surveying the present right-of-way of the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad, founded the city of Huntington.”

For the 10 a.m. ceremony, Mrs. Mary Parsons Shrewbury, a grandniece of Collis Huntington and a city resident, pulled the string which released the canvas that covered the statue. Also participating were city, state and C&O officials as well as prominent local citizens. The ceremony also featured the newly-organized Huntington Boy Scout band.

Howard L. Ferguson of Newport News, Va., former vice president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and president of the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., an enterprise founded by Collis Huntington, officially presented the monument at the request of Henry E. Huntington, nephew of the city’s founder who was unable to attend.

The statue was given by the late Mrs. H.E. Huntington, who was Collis Huntington’s second wife and his widow, who herself had died just six weeks prior to the dedication.

The monument was accepted for the city by Mayor Floyd S. Chapman and for the C&O by its president, W.J. Harahan.

The statue was the work of internationally-known sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who is best known as the sculptor of the colossal heads of the four presidents carved in the face of Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

No other single event contributed to the building of the city of Huntington more than the coming of the C&O Railway. It was the powerful financial resources of Collis Potter Huntington that laid the foundation for the city that would greet his new railroad line emerging from the rugged mountains of Appalachia.

Huntington’s association with the C&O began in June 1869 when the president of the newly-organized line, General William C. Wickam, of near Richmond, Va., asked the financier to invest in the struggling Virginia railway which was then hopelessly stalled at White Sulphur Springs, just inside West Virginia’s eastern border.

Gen. Wickam had read of Huntington’s success with the Central Pacific Railroad which had culminated in May 1869 with the first transcontinental rail link with the Union Pacific at Promentory Point, Utah. He would try to sell the railroad builder on the idea of buying the C&O and trans-forming it into a top-rate trunk line from the Atlantic to the Midwest.

Intrigued by the idea, in late June Huntington and his associates left their New York City offices for Washington, D.C., where they caught a train heading west. His party stayed at the future resort town of White Sulphur Springs in July while they explored the route that had been surveyed to go over the mountains. The route was further plotted along the New River to the Gauley Bridge, through the Kanawha Valley to St. Albans, then across Teays Valley to the Ohio River, near the mouth of the Guyandotte River.

By November, Huntington had put together a syndicate of investors and raised $850,000 with which he purchased the C&O. Later that month he was elected president of the railroad at a reorganizational meeting in Richmond, Va. He also gained control of the board of directors.

According to a biography, not until the financier had bought the new railroad and had control of the board of directors did he inform his California partners of his new venture.

During the winter, a western terminus was selected near the small settlement of Holderby’s Landing, on the Ohio River between the Guyandotte and Big Sandy rivers. Huntington made several trips into the area with his brother-in-law, Col. D.W. Emmons.

A story is told that the financier was supposed to have chosen Guyandotte, three miles to the east, as the western terminus of his C&O Railway. But an incident during one of his early visits changed his mind.

“On one occasion,” reported the Huntington Herald-Advertiser of Nov. 2, 1930, “the magnate was fined in the (Guyandotte) mayor’s court because his horse, tied in the street, swung about to take a position on the side-walk … the incident of the fine led Mr. Huntington to the decision to build a new city to the west of Guyandotte River, one which was destined to absorb and engulf its so much older sister.”

According to tradition, during one of his visits Collis Huntington was a guest at the Madie Carroll House in Guyandotte. The house, the oldest in Cabell County, was then an inn used by travelers on the James River and Kanawha Turnpike.

The new president of the C&O was born in Hartford, Connecticut on Oct. 22, 1821, one of nine brothers and sisters. The area in which he grew up was called “Poverty Hollow.” He later moved to New York State where he became a small merchant, a “Yankee peddler.”

Seeing opportunities in California during the 1849 Gold Rush, Huntington set sail for the West Coast. Biographers have written that while waiting for three months in Panama for a northbound ship, the New York merchant sold goods. After leaving New York with $1,200, he paid all his traveling expenses and still arrived on the West Coast with $5,000 in hand.

When Huntington arrived in California, the main hotel in San Francisco rented for $110 per year, food was $25 a week, and money was loaned at 14 percent a month.

Huntington then headed for Sacramento where he opened a hard-ware store. A biography says that Collis did not smoke, drink or gamble, adding that he slept in his store and was at work before any of his clerks. His philosophy was that if one took care of the small things in business, the big ones would take care of themselves.

In partnership with Mark Hopkins, Huntington made his fortune and became one of the “Big Four” who built and linked the Central Pacific to the Union Pacific in the first transcontinental railroad.

A biography explains that “when Huntington and his business partners set out to build the Central Pacific in January 1863, none of them had any expertise in railroad construction or management; nor were they independently wealthy.” Despite these handicaps, they succeeded in building 1,086 miles of track by May 1869.

Before the Central Pacific was finished, the Pacific Association had extended their operations to what later became the Southern Pacific Co., which Huntington and his partners developed into a rich empire with mines and ocean shipping as well as long railway lines.

Historians have put Collis P. Huntington in the company of such moguls as Commodore Vanderbilt, a man whose overriding obsession was accumulating wealth. Over time, Huntington has been called “an empire builder” and a “robber baron.”

Contemporary observers described Collis Huntington as “a very impressive-looking man.” He stood 6 feet, 4 inches tall with broad shoulders on a massive frame. His neatly trimmed beard gave his face “a perpetual scowl,” according to one account. But, his skill at business negotiations earned him the title of “The Great Persuader.”

In May 1870, the wood-burning locomotive “Greenbrier” was floated down the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers so that construction on the C&O could begin from both ends. That summer Huntington personally inspected the route, riding over most of it on horseback. A biographer writes that during this journey, Huntington “looked colossal” as he sat astride a long-legged horse large enough to support his bulk.

After construction began, his new city was laid out on ground fronting the Ohio River.

With the help of Col. Emmons and Attorney Albert Laidley, acreage was purchased and set aside for railroad shops, yards and station facilities. The remainder of the 5,000 acres was turned over to the new Central Land Co. for sale to prospective residents.

During the winter of 1870-71, Huntington commissioned Rufus Cook, a renowned Boston engineer, to lay out the new town along some 5,000 acres of bottomland. The care-fully constructed grid pattern, with its many broad streets and avenues, was a marvel of foresight, anticipating an automobile age which had not even cast its shadow at the time.

In order to build population, the C&O’s repair shops were located in the new city as well as several rows of houses along Eighth Avenue for railroad workers and their families.

On Feb. 27, 1871, the city of Huntington was granted her charter by the West Virginia Legislature.

According to local histories, the first city election was held on Dec. 31, 1871, at the Marshall (College) Post Office and Peter C. Buffington was elected mayor.

As construction pace increased in 1872, people moved to the new city in large numbers from New York state and New England.

It was expected that the C&O mainline would be completed in the fall of 1872 but bad weather had delayed the work. But, on Jan. 29, 1873, the last spike was driven at a point near Hawk’s Nest, W.Va., and the work connecting Huntington to Newport News, Va., was complete.

At 11 p.m. that evening, the newspaper reported that the temperature was 10 degrees below zero in the new city of 3,000 residents. Fog rising from the Ohio River turned to ice crystals and felt like snow on the two steel rails which lay before the new station that faced Eighth Avenue.

Rail touched rail for 419 miles through valleys and narrow gorges, over whitewater rivers, across high forested mountains, and through some 10 tunnels bored through the mountains from the banks of the Ohio River to the James River in Virginia.

To mark the historic event, a black-iron engine slowly pulled its load of dignitaries, passengers and freight into the Huntington depot. The first train, which had left Richmond on January 23, had arrived in the new city. East met West.

On its return trip, the train reached Richmond amid much fanfare on the morning of February 13. Attached to it were several carloads of coal from the Kanawha coal fields to be examined and tested. Also aboard that historic train was a large container of Ohio River water to be poured into the James “thus consummating the marriage of west and east knitted with bands of steel never to be dissolved,” proclaimed a newspaper of the day.

The city of Huntington did not enjoy the status of a railroad terminus for very long. Collis Huntington began extending C&O tracks westward from his namesake city in 1879. A train from Lexington, Ky., to Richmond passed through town on Dec. 12, 1881, states a local history.

The railroad magnate lengthened his railroad along the Ohio River, and by 1882, had trains running from Covington, Ky., to Richmond. However, he also wanted a water level route into Cincinnati. He bought out a Kentucky railroad that was bankrupt and on Christmas Day 1888, the first train passed over the new route running from Richmond to Cincinnati and through Huntington and Ashland, Ky.

Collis Huntington’s plan was to extend the C&O and Southern railways to New Orleans to connect with the Southern Pacific, completing the coast-to-coast railroad of his dream. It was not to be. Revenues from the new roads could not keep pace with expansion. The financier wished to focus his attention on matters concerning his western holdings and, in July 1884, the C&O was sold.

By this time changes had also taken place in Huntington’s private life. A biography states that in the 1860s, Huntington and his wife, Elizabeth, moved from California to New York City where he purchased a house on Park Avenue for $50,000. Early in that decade the Huntingtons adopted a child, Clara, who was Elizabeth’s niece. In 1883, his wife Elizabeth died and Huntington remarried Arabella Duval Yarrington, of Alabama, in 1884. A biography added that, “Collis was 63, his bride 34 or so.”

In October 1889, Collis’ daughter, Clara Prentice Huntington, left New York for London to become the bride of a German prince.

The Huntingtons, with Arabella’s young son, Archer, whom Collis adopted, lived in his Park Avenue house while a house on Fifth Avenue was being built, states a biography, adding that during this time the family made several trips to Europe.

According to a biography, the Huntingtons’ new residence at Fifth Avenue and 57th Street was “of princely magnificence, notable among all the palatial structures of multi-millionaires in New York.” The book adds that the building, completed in 1893 at a cost of more than $2.5 million, “was richly furnished” and included paintings by great artists, beautiful tapestries and other works of art.

On August 13, 1900, Collis P. Huntington died after suffering an apparent heart attack at his and Arabella’s summer retreat in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State. He was 78. Following a funeral service at his New York City home on August 17, Huntington was buried in a mausoleum at Woodland Cemetery, near Throg’s Neck, N.Y.

A biography reports that at the hour of his funeral, and for seven minutes thereafter, 5,000 men (his employees) became idle, engineers paused on the rails, ships floated motionless upon the water, telegraph instruments ceased to click and his offices became silent. At the time, Huntington was recognized as the leading railroad builder in the nation.

One of his legacies was an outstanding collection of paintings that he willed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Huntington’s favorite charity was the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute near Newport News, Va. The school was established after the Civil War to help freed slaves and later, to help Native Americans learn a trade and become self-supporting. Huntington also supported Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by Booker T. Washington, and he helped establish the Hispanic Society of America.

The financier also was one of the original contributors to the building of the First Congregational Church in Huntington at Ninth Street and Fifth Avenue in 1874, according to a local history.

A biography explains that Huntington’s estate was divided into thirds among Arabella, Archer Huntington, and Collis’ nephew, Henry E. Huntington.

Two-thirds of the massive estate were reunited in 1913 when Arabella married her husband’s nephew, Henry. Henry added to his fortune with streetcar lines and real estate in southern California. Arabella continued to live in the residence on Fifth Avenue where she died on Sept. 16, 1924. A biography states that soon after her death, the building was torn down and this corner now is the site of Tiffany’s.

Aside from the railroad itself, the Tri-State had had no direct contact with Collis Huntington or his family since the sale of the C&O in 1884. It came as a mild surprise when, 40 years later, the city was selected as the site for a statue of the railroad king.

The installation of the statue in 1924 seemed appropriate since Huntington definitely was a C&O town. In the early 1920s, there were 2,250 men employed at the sprawling C&O shops on 8th Avenue.

By the late 1930s, total C&O employment in the city exceeded 5,000. That year there were 25 passenger trains arriving and departing daily at the three-story C&O station on Seventh Avenue and about 50 freight trains passed daily east and west through the depot. Hotels and restaurants near the massive midtown station catered to passengers and crews of C&O trains.

Traffic loads on railroads remained at heavy levels as the Depression years wore on and with the massive mobilization of World War II. But in the peacetime that followed, passenger traffic fell to drastically low levels. The blame was placed at least partly on the rise of the private automobile.

As passenger trains began being discontinued around the country in the 1950s, the C&O tried some last ditch efforts to keep a thriving passenger trade.

During the 50s and 60s, the passenger program gradually dwindled until by 1971 only one C&O train eastbound and westbound remained. That year, Amtrak, the newly-created national passenger rail service, took over all long distance passenger trains in the United States.

With the C&O out of the passenger business, its lucrative coal and freight hauling business expanded.

The architecturally significant C&O depot in Huntington, built in 1913, has remained remarkably well-preserved up to the present time and was used as a passenger station until 1983 when Amtrak moved into its own station across the tracks on Eighth Avenue near 10th Street. The old waiting room was converted into a centralized traffic control and dispatching center that monitors the C&O from Hinton, W.Va. to Cincinnati and Columbus. The long trainshed that once protected passengers and visitors standing on the platform from the elements has since been completely removed.

Although Amtrak runs only one train, the Cardinal, east and west three days a week, Huntington remains a railroad city. Day and night the trains of CSX Transportation (the successor to both the C&O and the B&O) rumble through town bearing coal, chemicals and manufactured products from West Virginia and bringing in automobiles and other manufactured goods and luxuries to the people of the state.

Like the C&O before it, CSX is a major employer in Huntington and its repair shops alone employ hundreds of workers on land originally planned for that purpose by Huntington.

Even today, the name “Chesapeake and Ohio” can conjure images of a line of heavy coal cars in tow behind the massive power of several locomotives amid rugged mountains, or of polished engines pulling long, sleek passenger trains winding around forested hills and whitewater rivers.

In May 1977, the Huntington statue was moved on a flatbed truck from in front of the C&O passenger station to its new home in Heritage Village, which is under the supervision of the Greater Huntington Park and Recreation District.