A retrospective of Huntington’s most elegant hotel from the past.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 28 | SPRING/SUMMER 1997

Dashing inside the Frederick Building on a cold February day for my appointment on the fifth floor brought back some old memories of the hotel. I can recall attending wedding receptions in the Georgian Terrace on the hotel’s mezzanine and dinners in some of the private, upstairs dining rooms. I also remember the exceptionally wide, carpeted hallways on all of the upper floors and the times I walked through the lobby from the Fourth Avenue entrance to the 10th Street side when I worked at George H. Wright’s.

For more than 90 years, the dignified, unostentatious, five-story, dark red brick Frederick Building has been a landmark at the intersection of Fourth Avenue and 10th Street, once dubbed “the main corner of town.”

No longer in use as a hotel, the Frederick Building now contains offices and retail stores on the street level.

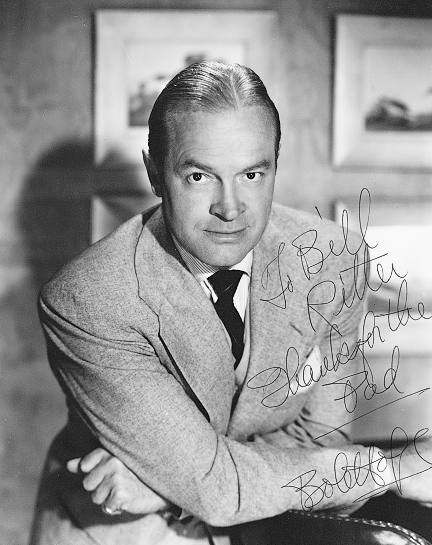

Although the Frederick Hotel closed in June 1973, a review of its guest registers from past decades would find such names as Bob Hope, Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontaine, Henry Fonda, Helen Hayes, Marge and Gower Champion, and Liberace as well as the signatures of many other celebrities of the 20th Century. Most of the opera singers, actors, actresses, dancers and musicians who were on the bill of the Marshall Artists Series, which began in 1936, were lodged in the Frederick’s plush suites. Guest registers would also contain the names of thousands of traveling salesmen and saleswomen. Local retail merchants state that the Frederick was “the hotel of choice” of company sales representatives who came to Huntington on business.

An article in the Herald-Advertiser (Huntington) Centennial Edition, July 11, 1971, states: “The Frederick was known by the public as the most elegantly furnished and best-equipped hotel in the state.”

During its heyday, the Frederick lobby with its rotunda and ornate main staircase was a lively place with well-dressed men and women waiting at the front desk to check in or out of the hotel. Guests in the lobby would sit in large chairs or sofas and pick up their mail and messages. Life was less hectic then.

Because of the hotel’s many private dining rooms and the Georgian Terrace on the mezzanine, the Frederick is remembered as “the center of social activities in Huntington.”

The hotel also was known for the many shops and businesses that leased space along its street level.

In 1906, the year the Frederick Hotel first opened its doors, Teddy Roosevelt was in the White House and ragtime was the popular music of the day. That year the growing city of Huntington could boast of having electric trolleys rolling on slender rails down the center of Third Avenue. Electric lights illuminated some downtown streets, and there were several nickelodeons in business. There also was the new Carnegie Library for the reading public in a city with a population approaching 30,000.

Huntington had some other hotels including the popular Florentine on the southeast corner of Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street.

Although muddy streets and picket fences still were commonplace in Huntington in 1906, “the majestic Hotel Frederick had been erected on the northwest corner of 4th Ave. and 10th St. to remind the city that the modern age was coming,” states a newspaper article.

Built at a cost of $400,000, the hotel was designed to offer the finest of social amenities to be found anywhere along the Ohio River between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Named for George Frederick Miller, a Huntington financier and one of the hotel’s promoters, it had five floors, covered five and a half acres of floor space, and was constructed with 3.7 million bricks — quite an achievement for its time.

The Frederick was designed by Huntington architect James B. Stewart who, several years earlier, had designed the Carnegie Library at Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street.

George S. Wallace in his Cabell County Annals and Families writes that “in 1906 George F. Miller and his associates built the Frederick Hotel and began the development of 4th Avenue.”

Miller was executive vice president of the First National Bank from the date of its organization in 1888 and was an outstanding figure in the development of the city.

In March 1905, ground was broken for the Frederick Hotel.

An article in the Huntington Advertiser of April 15, 1905 states that the first story of the new hotel “is to be of Berea sandstone, the Advertiser of April 15, 1905, states that the first story of the new hotel “is to be of Berea sandstone, the city has ever been pushed to completion with such remarkable dispatch as that which has marked the work on the Frederick.”

William B. Newcomb, of Huntington, a retired officer of the former Anderson-Newcomb Co. and a local historian who now is in his 90s, has recalled the Frederick in its heyday. In a 1973 newspaper interview, Newcomb states that the hotel’s well-pre-served exterior can be attributed to the special “hardened brick” used in its construction.

Furniture for the new hotel cost between $75,000 and $100,000 and was obtained on furniture-buying trips to Chicago. The article adds that “the furniture will be of the very best to be obtained and thoroughly in keeping with the magnificent house that must stand through the years to come as testimonial to the ability of Huntington’s hotel men to give the public the best there is.”

The Frederick Hotel was opened to the public on Monday, Nov. 12th, 1906.

According to a newspaper article, it was not the intention of the hotel to open prematurely, “but seeing the urgency of more hotel rooms for the accommodation of the crowds that will be here during the week, it was decided to open the dining room and such apartments as were ready for occupancy.”

Historical accounts state that the first meal served in the Frederick Hotel was for the workmen who completed the brick laying on Jan. 5, 1906.

The Huntington Dispatch of Jan. 6, 1906 reports:

“L.H. Cox, a member of the company having the building erected, treated the laborers on the building with a fine dinner, the first ever served within the walls of the hotel. These men having labored faithfully and regularly and it was in appreciation of the rapid progress made possible by their faithful labors that the dinner was being given. It was supplemented by a few kegs of ‘West Virginia’ (beer) and a box or two of cigars.”

Wallace writes that “L.H. Cox and R.L. O’Neil organized an operating company and took charge of the Frederick which immediately became the popular hotel.”

L.H. Cox and his brother, R.L. Cox, had come to Huntington in 1894, and, in 1901, had taken over the operation of the Florentine Hotel at Ninth Street and Fourth Avenue. Dick O’Neil, L.H. Cox’s nephew, “was the genial and popular clerk” at the Florentine before he switched to the Frederick when it opened, states Wallace.

Those who financed the construction of the hotel were lumberman C.L. Ritter, L.H. Cox, George F. Miller and C.W. Watts, who together formed the Central Realty Company.

Once the hotel was completed, it was leased by the Frederick Hotel Company. The company was composed of George F. Miller, president, L.H. Cox, vice president, and R.L. O’Neal, secretary and treasurer.

The Frederick’s original 125 rooms were described as “elaborate in every respect with all the modern conveniences such as hot and cold water, baths, private telephones …”

The hotel entrance was at the center of Fourth Avenue and led to the lobby which was 61 feet wide and 42 feet high from floor to ceiling. The lobby passage led to the men’s bar and billiard room and the checkrooms. The lobby also led to “the marble grand staircase” leading to the second floor and the balcony. The hotel also featured a fireplace, writing rooms and a special ladies entrance.

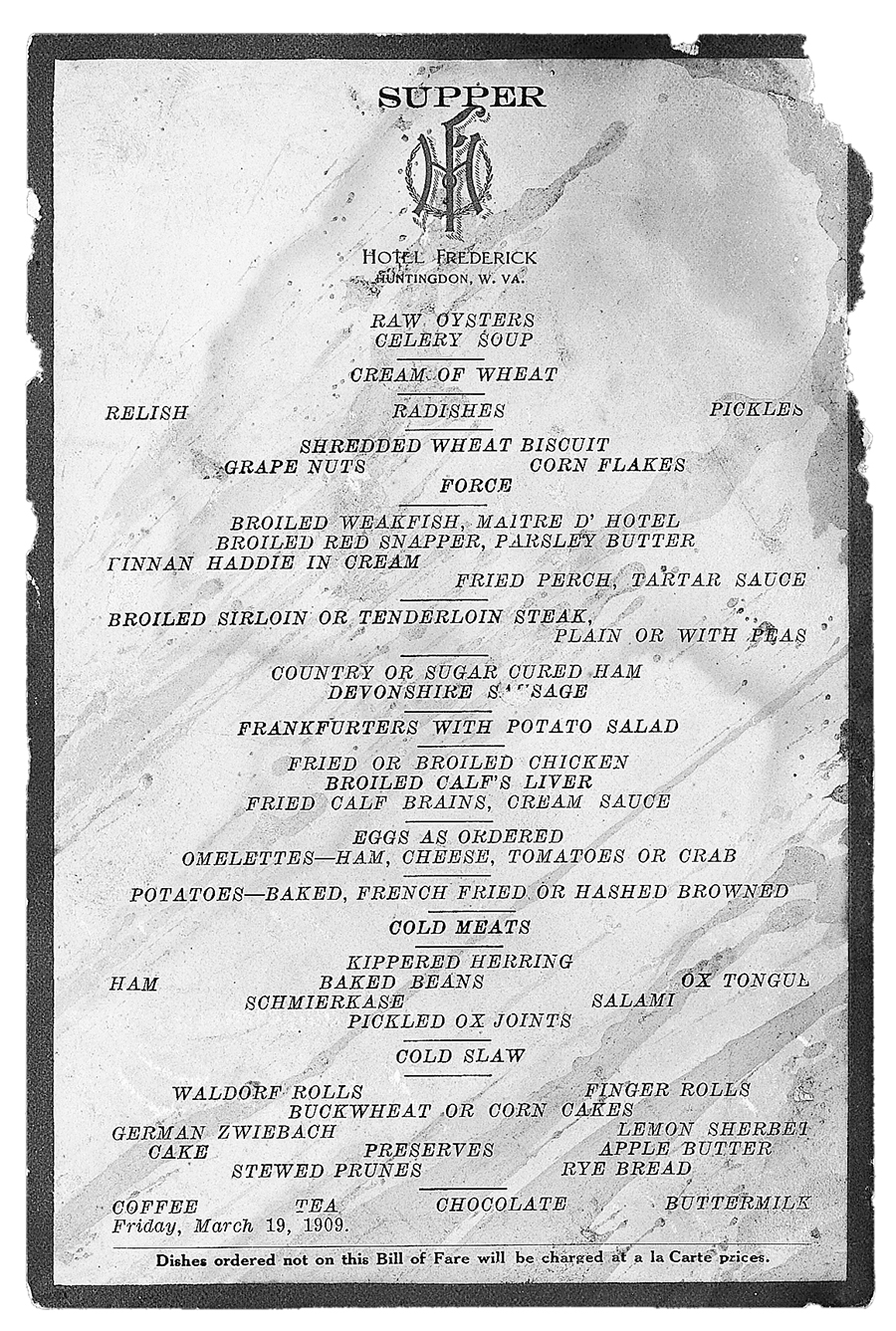

At the south end of the balcony (mezzanine) was an area for the “ladies parlor” overlooking Fourth Avenue. On the west end of the balcony was “the ordinary dining room” while on the north side, between the stairways, was the entrance to the main dining room. Also on the west end of the balcony were the kitchens, bakery, pastry department, servants dining rooms, kitchen elevators, cold storage rooms for meat and dairy products and dumb waiters for the cafes below.

The entire building was heated by steam radiators and there were three 150-horsepower boilers which furnished heat and power. Also in the basement were two 65-feet deep wells with pumps to draw up water to fill tanks and filters for the use of the entire building. South of the boiler room under the lobby were the ice and refrigerating plants that had a capacity of producing 12 tons of ice per day.

The building had 45 private bathrooms that were “furnished with the best enameled iron tubs, lavatories and closets with tile floors and tile wainscotted walls four feet high. All rooms not connected with baths were furnished with hot and cold water in enameled iron lavatories. On the north end of the lobby was a stairway leading down to the “Turkish bath department” located in the basement which included “hot vapor rooms and rubbing slabs.”

The article reports that in addition to 3.7 million bricks, the amounts of material necessary for the hotel’s construction and furnishing included one-half mile of concrete walls, two feet thick, 10,000 cubic feet of stone, more than 4,000 electric lights, 200 telephones, 63 miles of telephone wire, 252 miles of electric light and power wire, 310 bath and lavatory fixtures, more than 300 tons of iron work, five carloads of glass, and more than 50,000 square feet of roof to cover the building.

Wallace writes that “erection of the Frederick Hotel on Fourth Avenue was regarded as a tremendous experiment as there was no business on this avenue . . . The new hotel was larger than the immediate business would justify but the ground floor along 10th Street were rented for offices.”

A 1970 newspaper article states: “When the Hotel Frederick first opened its doors in downtown Huntington in 1906, one of the most talked-of features in the plush interior was an elaborate stained glass window in the lobby rotunda.”

The Frederick is first listed in the 1907 city directory with room rates of “$2.50 to $4 per day.” L.H. Cox is listed as president of the hotel and R.L. O’Neal as secretary-treasurer.

An advertisement for the Frederick in the 1924 directory states: “A First Class Dining Room on Mezzanine Level” and “Popular-Priced Lunch Rooms Off Lobby.”

About 1928 George H. Wright moved his men’s clothing store into space on the hotel’s street level on 10th Street beginning the retail clothier’s long association with the Frederick Building.

During the hotel’s early years, the Frederick Pharmacy was a large drugstore with fountain service located on the street level with its entrance on the corner of Fourth Avenue and 10th Street.

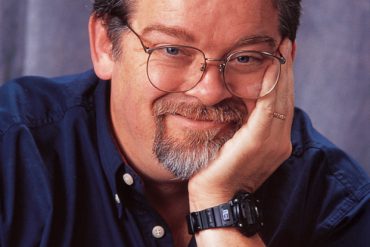

William R. Ritter Jr., president of the Central Realty Company and current owner of the Frederick Building, states that today there are between 30 and 35 businesses as tenants in the building.

Ritter, who has been associated with the Frederick since 1960, says the hotel had as many as 160 employees including part-time help during the busy Christmas holiday banquet and dinner season and for conventions.

Ritter, whose grandfather, C.L. Ritter, was one of the local businessmen who financed the construction of the Frederick, says that originally the 10th Street side of the building was intended for offices and stores.

Ritter states that the hotel’s main dining room was called “The Colonnade” and its entrance was at the north end of the lobby. The Frederick also had 12 private dining rooms on the second and third floors and there was a ballroom on the third floor for dances to the music of big name orchestras. He adds that the private dining rooms had such names as the Rose Room, Rotunda Room, Marquis Room, Baronet Room, Crystal Room and the Continental Hall, which was composed of four rooms that could be opened into a large hall.

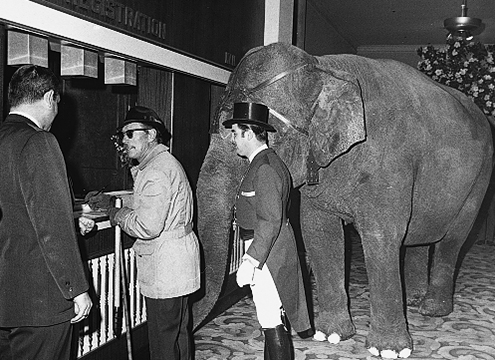

The Elephant Walk was the hotel’s private club and it opened in the early 1960s. Prior to the club, the room, located on the west side of the lobby, was used for men-only luncheons.

Later in the day the room was open to all guests. The Elephant Walk later was the site of Ming’s Restaurant. The Hotel Frederick had valet parking and leased the lower level of the parking port across 10th Street for guests’ cars.

Ritter explains that hotel suites were typically reserved for use by corporations, by the Marshall Artists Series for guest performers, by salesmen, and by celebrities visiting Huntington.

Spring and fall generally were the hotel’s busiest seasons and Ritter adds that convention business became more important as the years went by.

According to Ritter, Huntington was known as “West Virginia’s Convention City,” and the Frederick could handle “in-house” conventions of as many as 200 people.

During the hotel’s early years, The Colonnade (main dining room) was the site of the men’s bar and billiard room.

Ritter explains that during the early years of this century when the Frederick opened, it was considered inappropriate for an unescorted woman to enter a hotel through the main entrance so there was a separate “ladies’ entrance.”

Ritter says that during the early 1900s, an employee wearing the Frederick’s livery would meet a customer at either the C&O or B&O depots and take him to the hotel in a horse-drawn buggy. Other “liveries” would pick up the luggage at the depot and take it by wagon to the back of the hotel where it was taken to the guest’s room often before he had finished checking into the hotel.

Traveling salespeople made up a large percentage of the hotel’s business. One of the Frederick’s unique features was large “sample rooms” on the fifth floor where traveling sales representatives could set up their racks of goods and local retailers could inspect the merchandise.

Ritter recalls the names of some of the celebrities who stayed at the Frederick including Bob Hope, Liberace, Imogene Coca, actor Franchot Tone, and Broadway singer Gordon MacRae. Many of the celebrity guests were on the bill at the Marshall Artists Series playing across the street at the Keith-Albee Theatre. Boxing great Joe Louis and then Vice President Richard Nixon also were guests at the Frederick.

Ritter explains that operating the Frederick Hotel was a “labor-intensive” business. He cites as an example that all of the private dining rooms were on the second and third floors and adds that with minimum wage laws, labor costs climbed and there was always a need for more parking space. Closing the hotel at the end of June 1973 “was a business decision made for economic reasons,” Ritter explained. “But even though it’s been 20 years since we closed the hotel, we still get calls from people who want to reserve one of our banquet rooms.”