Regional artist Adele Thornton Summerfeldt brings canvas to life with her breathtaking perspective of people and places.

By Kathy Young Carney

HQ 29 | AUTUMN 1997

A cluster of paint smudges has settled at the tail of one of her better work shirts. Cotton swabs, tipped in more paint, litter the floor of her work room. But it’s not what’s on the shirt or the swabs that have built a reputation for Adele Thornton Lewis (now Adele Thornton Summerfeldt). It’s what ends up on the canvas that has made the artist popular.

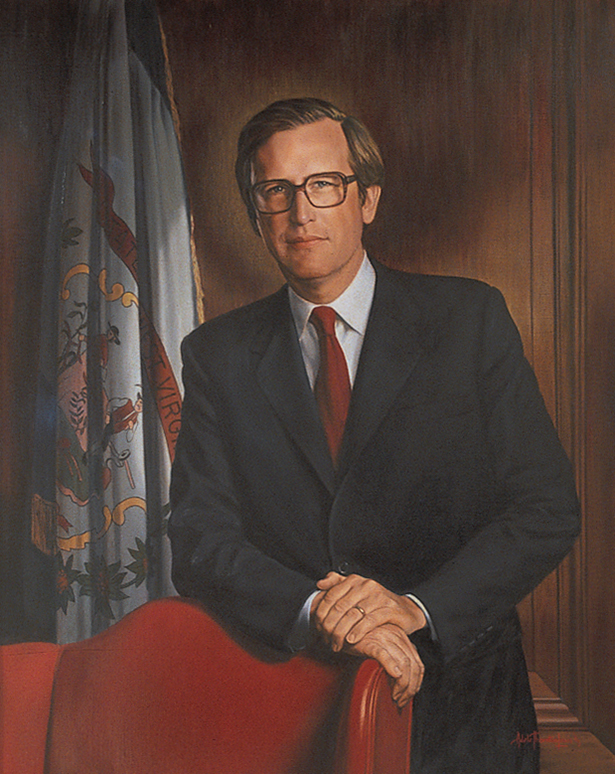

The Huntington poster with the riverboat (1,000 copies have sold out), the Chuck Yeager portrait at Marshall University, former Gov. Jay Rockefeller’s portrait hanging at the state capitol — all bear the distinctive Adele Thornton Lewis signature. Add to that list the portraits of local notables, famous sights, soft landscapes, and you have an impressive resume.

But Adele shuns the idea of being famous and she laughs at the idea that her signature is a status symbol. “I become embarrassed and uncomfortable with that notion,” she said. “I have been around so long, I am a commodity.”

She’s a hot commodity. At times Adele is booked a year in advance. Her clientele is willing to wait. They are also willing to pay the minimum of nearly $2,000 for a head-and-shoulders portrait. That’s a long way for a mother whose first commissioned painting of redbirds for a friend some 35 years ago sold for $12. She remembers how hard it was to build a collection for a showing back then.

“When bringing up two babies, it is difficult to accumulate anything because painting time is limited. In addition, I just didn’t charge enough for my work. Finally, one day my ex–husband said, ‘Don’t you think you could get up to a dollar an hour?’ I remember taking 65 hours to paint a watercolor portrait, and I charged $65. I was so proud of the income.”

Hers is a career that had a slow beginning, although talent runs in her family. Both Adele’s mother and aunt were painters, but it took her a while to realize she had the makings of a professional artist.

“I wasn’t interested in painting as a teenager. I never had the opportunity to take an art class until I went to college. Then when I came to the place in life where my two oldest children were in school, I started painting.”

Other mothers may reserve their children’s nap time to do housework, but Adele used those few precious hours to paint. When the kids woke up, everything was shoved under the sofa for another day. That’s why she stuck to watercolor in the beginning. Oils are messy; not something to be shoved under the sofa.

Slowly but surely she built up enough paintings to exhibit and sell. The money was enough to pay for supplies and help out with the household budget.

So what do you do when you have a box full of paintings, no money, and the desire to go on vacation with your children? You do a little wheeling and dealing. Adele landed a beachfront house every time she wanted to head south. All it took was a telephone call, a showing and a little bartering.

“I’d get in contact with a small gallery and arrange to have a show.” The gallery rep typically had clients with beachfront homes, and would put Adele in touch with an owner. They, in turn, would offer to lend her their home in exchange for a commissioned work.

From the beach to whitewater rafting to skiing, Adele has been offered similar arrangements. Not bad for a struggling artist.

After a few years of dabbling and selling, Adele found she could earn money teaching other people to paint. Maybe it would be better to say teaching found her with the help of some sneaky friends — Bill Meadows and Fred Gros.

Meadows and Gros were involved with the Huntington Galleries (now the Huntington Museum of Art) and decided someone should teach how to paint with watercolor. The twosome also decided Adele was perfect to teach the class. They approached her with their idea. Adele says she was panic–stricken at the thought and tried to make it clear that she was not a teacher.

“The way they got me,” Adele explained, “is by printing the art class brochure with my name in it as the teacher. And it was already mailed out. Talk about being on the spot.”

Meadows, a local potter, laughs when he remembers the trick. “We knew she would be a good teacher. She just needed a little shove. Adele and I kidded a lot and I knew what I could get by with.”

Adele protested but the persistent friends won. It was difficult to back out gracefully once her name was in print. She took the job. Her friends’ only guidance was to “just get up there and do what you do at home.”

“But my students learned nothing because what I do at home is wet the paper, paint the color on heavily and play in it. That’s not formula teaching for people who haven’t touched watercolor at all. But, they put up with me and they came back just for the show.”

The show was good enough to make the job last 12 years. After two years of teaching watercolor, she added oil painting to her classes for the next 10 years.

Meadows thinks teaching helped her improve on her talent.

“I think she’s the best watercolorist in the area,” Meadows said. “I think that forced teaching job caused her to paint more. The more you work at something the better you get.”

Her friend remembers Adele being a sincere teacher who was really absorbed in her work, so much so that she was ripe for some more tricks from Meadows.

“I would sneak into her classroom and say something like, ‘Mrs. Lewis, what’s the number of the color you’re using now?’ (Insinuating she was painting by number.) She’d turn around all flustered,” Meadows laughed.

Things weren’t always so funny for Adele. Eventually, she was forced to choose a way to earn a living. Faced with a divorce and raising two daughters still at home, she needed a steady income.

“I either had to go type someplace or try art work.”

Her paintings brought in about $3,000 in 1978, enough encouragement to try the art work path.

“I decided, ‘I’ll go for it consciously and see what happens.’”

What happened: She made it. By 1982 she no longer had just encouraging words of friends and clients to bolster her career, she had a national honor — the West Publishing Company’s annual Art & Law Merit Award for “Belated Brief,” an oil painting depicting a lawyer working in the wee hours of the morning. It was the first of a two–part series Adele dedicated to a professional’s struggle for excellence. The second was “Difficult Diagnosis,” a similar painting of a doctor.

Ask her and she’ll tell you her success is “serendipity,” fortunate discoveries made accidentally. A chance to have highly publicized shows at a local bank, paintings turned into prints, and support from colleagues and the community transformed her life into a pretty rosy picture.

A large part, about two–thirds, of her commissioned work is oil portraits. Adele turns faces into pieces of art. People seek out her touch, her brush and her talent.

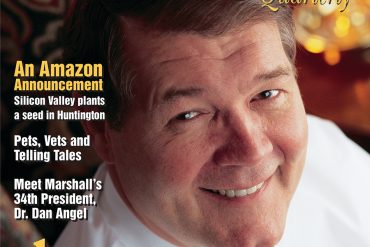

Marshall Reynolds’ likeness has come from her easel twice.

“She did a portrait of me at my wife’s request. She also did a portrait of my family at my request. She’s an amazing lady. She really has the ability to capture expressions and looks.”

“What made my work known is community support,” Adele said.

Ability had a lot to do with it too. It was ability that landed her the job of painting Rockefeller’s official portrait for the capitol.

Jay didn’t just pick up the telephone and give her a call. She and other artists from around the state submitted samples of their work for a “mystery commission.” At first no one was told that the winner would paint the official portrait of Rockefeller. The two–year competition came down to Adele and another artist. The former governor couldn’t make up his mind. Adele said as a tie–breaker Rockefeller used his own money and commissioned both to do a preliminary portrait of him. Adele won.

Adele and Rockefeller, now a U.S. Senator, never met before the project. However, during the little time they worked together, she made quite an impression.

“I am very fond of Adele Thornton Lewis,” Rockefeller said in a written statement. “I’m happy she’s become such a successful artist. The governor’s portrait she painted is the only formal portrait done of me during my adult life.”

“As an artist, Adele is very creative and ambitious, and as a person she is of the highest caliber. She may be soft spoken, but when I got to know her, I was impressed by how classy, intelligent and dignified she is,” Rockefeller said.

Adele painted Rockefeller as she does other portraits, from photographs. The toughest part of the painting? His lips. No photo supplied by the state was detailed enough. Adele took a trip to Charleston just to photograph Rockefeller and to get a good look at his lips.

“He is a very gracious man. He gave me all the time I needed on his last day in office, more than enough to gain all the information necessary to complete his portrait.”

The hardest part of that job? “The state’s requirements,” Adele responds. “I had to submit an infinitely long proposal, listing the cost on every color I’d use, the canvas, the brushes I would buy, framing and other supplies I had never had to figure before.”

Chuck Yeager is another face from her painting past. Adele doesn’t talk much about their meetings other than to say they didn’t see eye–to–eye on some things. However, her memorabilia includes a simple note from the general. “To Adele for a good job, Chuck Yeager.”

Keen eyes, or more importantly, those in–the–know, see something a little extra in the Rockefeller and Yeager portraits. Something that shows either the whimsical side, or perhaps the mischievous side, of the artist. Somewhere in all the tiny details sits a lone unicorn head, Adele’s symbol of a free spirit.

“I don’t put them in standard art work. I put them in paintings which are especially detailed,” Adele said. “I can’t explain why I add them in some pieces and not others. Something makes me think of it at the time I make my signature.”

“Half the fun of a unicorn in a commissioned piece is that I’m getting by with a light-hearted hidden detail. Nobody knows it’s there. Sometimes I’ll tell clients later.”

Don’t strain your eyes searching the entire pieces. For Rockefeller’s, check one of the bottom rhododendrons on the state flag. But don’t tell the Senator. He’s still searching for it.

The unicorn on the Yeager poster is behind the head of the topmost student. Unicorns also lie in hiding in the Huntington poster, Huntington Heritage (a fine art print the park board is marketing), and Difficult Diagnosis. You’re on your own.

In 1988 the Junior League of Huntington was knocking at Adele’s door. Members wanted a poster that would highlight the city. Adele convinced the league to consider a view of the Huntington skyline from across the Ohio River. The two teamed up and sales of the print raised thousands of dollars for community projects.

Jimelle Bowen co–headed the poster project: “She was very particular with the printer in Cincinnati regarding the reproduction of her painting. She wanted the colors to be as close as possible to what she had actually put on her pallet.”

“Everybody was very impressed. And she would sit and sign them. We never promised signing of them but she did a lot. She would sign them whenever anybody asked.”

Adele has spent a few months this year on her own, so to speak. She stopped all commission work for four months. This time the artist painted for herself, digging through old sketches and shoe boxes full of local, regional and travel photographs.

“It’s a little show for my own discipline. I want this body of work for me,” Adele said.

An exhibit at the Renaissance Bookstore from Thanksgiving through New Year’s Day will feature the new body of work.

Not only will her work be different — loose and slightly impressionistic — but so will her signature. She’s officially becoming, “Adele Thornton Summerfeldt.” She has been remarried for years and is finally ready to make the change on canvas. It’s not an easy move.

“For those years of the (first) marriage during which I painted, naturally “Lewis” is how I signed my name. But today I prefer to use ‘Adele Thornton Summerfeldt.’”

“For my show this fall, all the paintings done for myself in 1997 will be signed ‘Adele Thornton Summerfeldt,’ which is a big signature. But I need the ‘Adele Thornton’ there for my former identity and the ‘Summerfeldt’ for my happy identity.”

As for her future, Adele is confident that her reputation and body of work will keep her covered in paint. She adds that support from a community that likes what she does will continue to keep her career on track.

“I cannot describe how lucky and happy my life has been, overall.”