By James E. Casto

HQ 40 | AUTUMN 2000

Ask a cross-section of Huntington residents to list the city’s best mayors ever and you’re apt to come away with some sharp differences of opinion.

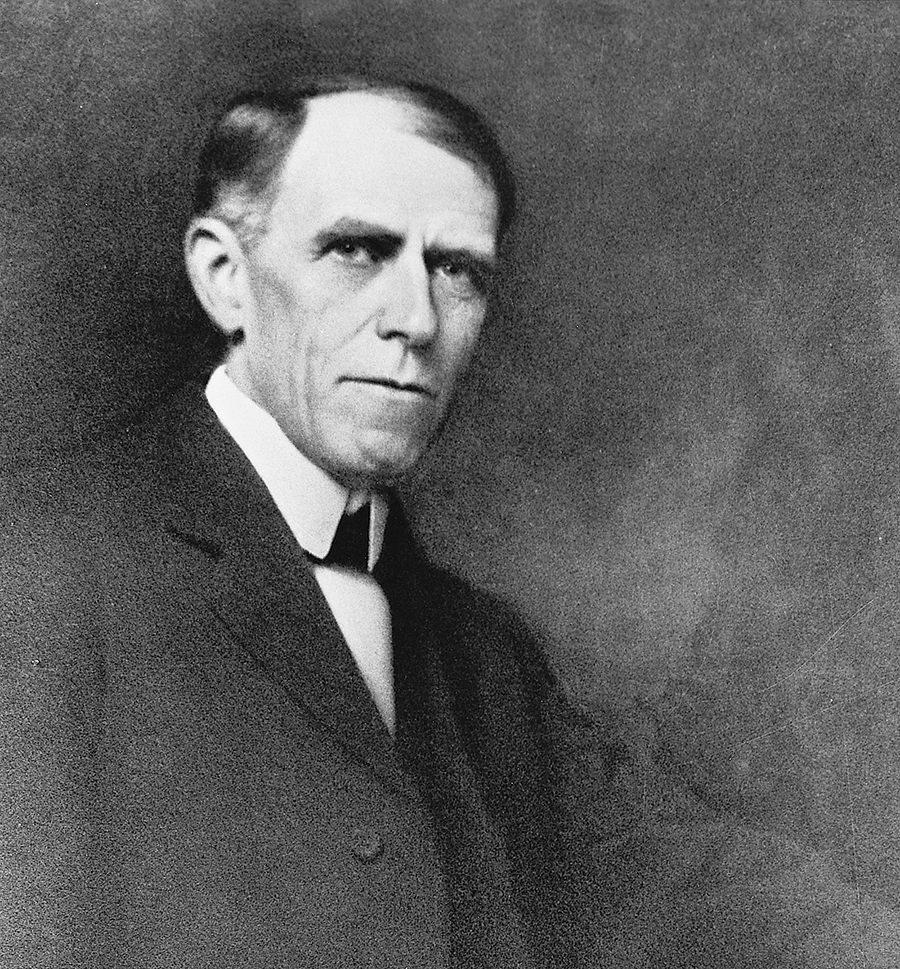

But few mayors would have stronger credentials to be on that list than Rufus Switzer, who served the city as mayor twice in the early years of the 20th century. A lawyer, banker and businessman as well as a political figure, Switzer was the father of one of Huntington’s best known — and best loved — landmarks, Ritter Park. And it was Switzer’s vision and generosity that helped bring the Huntington Museum of Art into being. That’s an impressive legacy, perhaps unequalled in the city’s history.

Rufus Switzer’s father, Jonathan Switzer, formerly of Botetourt County, Va., taught before the Civil War at Howell’s Mill, at that time called Doolittle’s Mill. In his “Cabell County Annals and Families,” the late George S. Wallace described the elder Switzer as “a scholarly gentleman, a splendid teacher, a leader in the community … (who) had the power of making friends of all in his large circle of acquaintances.”

Young Rufus, one of three children, apparently inherited many of his father’s fine qualities. Born Oct. 25, 1855, he was educated in the public schools, attended Marshall College, briefly taught school, then enrolled as a law student at the University of Virginia, graduating in 1881. That same year he started a law practice at Winfield in Putnam County. Four years later, he was elected to serve as a state senator, marking his first entry into the political arena. He came to Huntington to practice law in 1891 and immediately involved himself in politics, eventually winning election to City Council.

Oddly enough, Rufus Cook, the Boston surveyor hired by Collis P. Huntington to design the rail baron’s new town, made no provision for a public park. So, from the city’s earliest years, there was considerable public interest in establishing a park somewhere. Several proposals were offered but none came to fruition until Switzer was elected mayor in 1909.

The year before had seen the city purchase 55 acres of land on Four Pole Creek south of 13th Avenue between 8th and 12th streets as the site for an incinerator. Not surprisingly, nearby residents objected and a real donnybrook ensued. As mayor, Switzer settled the matter by taking the bold step of declaring that the purchased tract would be set aside as a city park.

Some grumbled that the tract was located too far outside town — then mostly confined to a few blocks of homes and businesses along the Ohio River. But Switzer effectively silenced all opposition when he announced that if the people did not want the land as a park he would take it off the city’s hands for the $18,000 the city had paid for it.

Although Switzer was the driving force behind the landmark project, the park was named for businessman C.L. Ritter. In return for the city building a road to his imposing hilltop home overlooking the site, Ritter donated two additional tracts of land and the area was unofficially dubbed Ritter Park.

It was also during Switzer’s first term as mayor that Guyandotte and Central City were convinced to become part of the city of Huntington and the so-called “Neutral Strip,” a no man’s land of sorts between Huntington and Central City, was annexed.

Switzer served as mayor until 1912, then was appointed to the post again in 1918 to fill the unexpired term of Mayor Leon S. Wiles, a victim of that year’s influenza epidemic.

Contemporaries described Switzer as a tall man with a lively sense of humor. His driving interest in life, it’s said, was the betterment of the community. From the 1920s through the 1940s, he was active as a lawyer, banker and real estate developer. In his Cabell County Annals, Wallace described him as “one of the builders of Huntington.”

Rufus Switzer died at age 91 on March 25, 194 7, but his influence remains very much alive today.

In his will, Switzer established a perpetual trust and directed that two-thirds of the annual net income from that trust go “for the use and maintenance of an art gallery, historical museum and cultural center, for the development of the character and interest of the children and other citizens of Huntington, Cabell County and West Virginia.”

In the Huntington Museum of Art’s formative years, Switzer’s generous bequest was literally the lifeblood of the institution. From its modest beginnings in the 1950s, HMA has since grown into one of the nation’s finest small museums. And it continues to profit from Switzer’s vision and generosity.

Switzer directed that the remaining third of the annual income from his trust go “for the study, research and treatment of human disease.”

The Huntington Clinical Foundation Inc. was organized to carry out the terms of Switzer’s bequest and for more than a half century has been active in the community, distributing thousands of dollars each year to a long list of projects in the medical and healthcare fields. The foundation is administered by a board composed of both lay people and medical professionals.

A handsome park, a thriving museum, a healthier community — that’s the legacy of Rufus Switzer, surely one of Huntington’s best mayors ever.