By James E. Casto

HQ 41 | WINTER/SPRING 2001

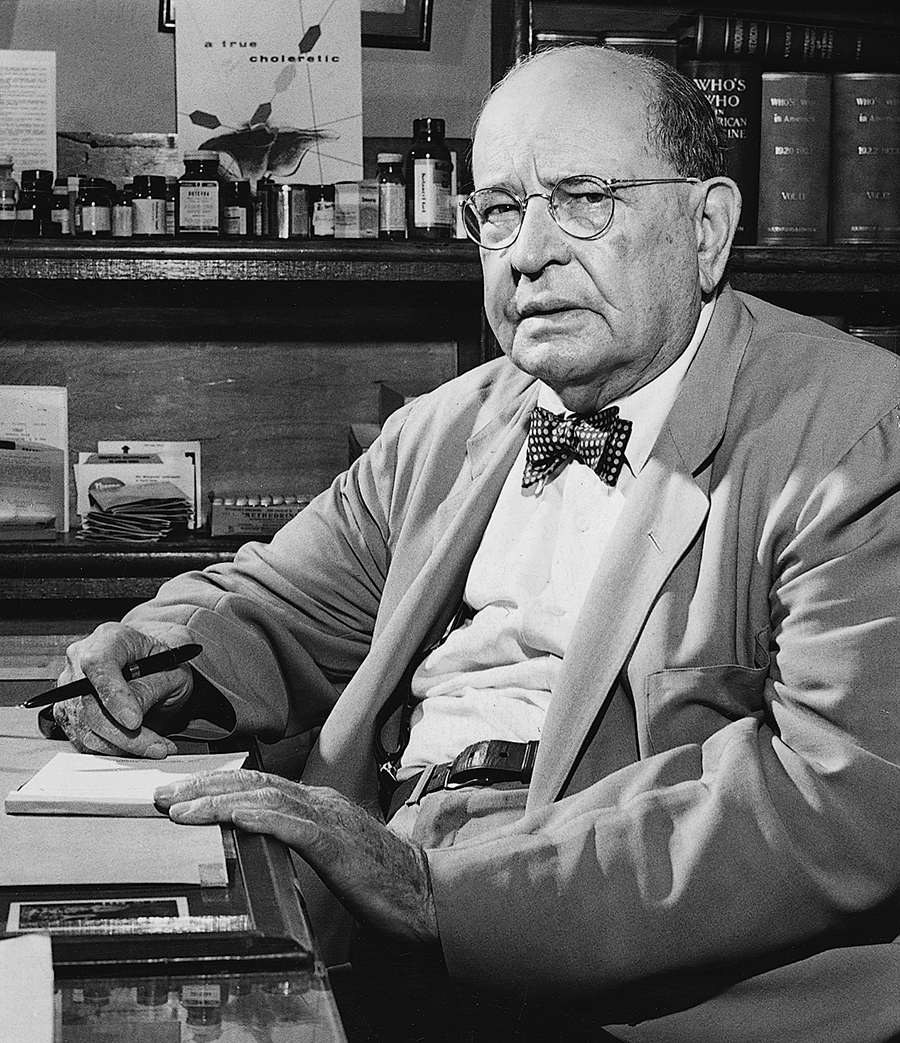

Dr. Henry D. Hatfield liked to describe himself as a “country doctor.” And he was. But he was much more than that. He served as governor of West Virginia, was a member of the U.S. Senate and achieved national renown as a surgeon. His was a crowded, busy lifetime, which saw him still treating patients until a few years before his death at age 87 in 1962.

A nephew of “Devil Anse” Hatfield, the patriarch of the Hatfield clan in the famed Hatfield-McCoy feud, the future physician/politician was born on Mate Creek in what is now Mingo County, then Logan County, on Sept. 15, 1875, a son of Elias and Elizabeth Chafin Hatfield.

He earned his bachelor’s degree at Franklin College in Ohio and medical degrees from the University of Louisville, Rush Medical School (now the University of Chicago) and New York University. He interned at New York’s Bellevue Hospital — a far cry from the coalfields of McDowell County, where he started his practice. Traveling by horseback to treat patients in isolated hollows, he more than once performed emergency surgery on a kitchen table with instruments sterilized in a bubbling kettle over a log fire.

The young doctor aided in establishing the State Miners Hospital at Welch and served as its chief surgeon for 14 years.

Always interested in politics, he became a member and then president of the McDowell County Court and in 1904 agreed to have his name placed on the Republican ballot for the West Virginia Senate to replace a candidate who had withdrawn. He was elected, twice re-elected and in 1911 became Senate president. His success in that post helped him win election as governor the following year.

When he was sworn in on March 4, 1913, at the age of 37, Hatfield was the youngest man ever elected West Virginia governor. (Two future governors — first William Maryland, then Cecil Underwood — would be even younger.)

The state’s southern coalfields were in turmoil when Hatfield took office as governor, with the United Mine Workers determined to unionize the mines and the mine operators just as determined to resist. Hatfield had been elected with strong support from the mine operators but also had sympathy for the miners.

“On the second day after my inauguration as governor,” he later recalled, “I decided to go into the coalfields where the trouble was raging and get a firsthand look at it. I talked to miners everywhere and got their viewpoint.”

The previous governor had declared martial law in the troubled coalfields and a military court had ordered legendary UMW organizer Mother Jones, then well into her 80s, jailed without a trial or even a hearing. For several weeks the old woman was locked in a cabin on the banks of the Kanawha River at Pratt in northern Kanawha County.

Visiting the cabin, Hatfield found her lying on a straw tick on the floor, carrying a temperature of 104, very rapid respiration and a constant cough. She had pneumonia. The governor immediately ordered her put aboard a train and sent to Charleston for treatment. He thought she would die but he underestimated the tough Mother Jones. After her recovery, she sought an audience with Hatfield and asked him if she could visit Chicago before going back to jail. “She said she would return to West Virginia when I sent for her,” Hatfield recalled. “I gave her permission to go. I never sent for her. I never meant to.”

Hatfield also appointed a committee to listen to both the miners and the coal operators and helped broker an uneasy truce between them.

As governor, Hatfield won enactment of a pioneering workers’ compensation system — patterned after a plan then in place in Germany — that would become a model for similar systems in other states. His determination that West Virginia needed such a compensation system developed, he later said, “out of my knowledge of the problems of the injured, sick and disabled miners in the coalfields where I practiced.”

Limited by law to one term as governor, Hatfield returned to his medical practice and became associated with Dr. A.K. Kessler in Huntington’s Kessler-Hatfield Hospital, later renamed Memorial Hospital. (Located at 6th Avenue and 1st Street, the hospital closed in 1958 and later was demolished.)

When the United States entered World War I, Hatfield joined the Army as a surgeon, entering service as a captain and coming out a colonel at the end of the war.

For many years, Hatfield treated patients at Memorial Hospital, at his downtown Huntington office and at two hospitals in Logan, which he also helped establish and visited weekly.

In 1928, his medical duties were interrupted when he was elected to the U.S. Senate. In Washington, he became a friend and confidant of President Herbert Hoover. Although he was defeated for re-election to the Senate in 1934, he would remain active in GOP politics.

As he grew older, Hatfield scorned suggestions that he retire, even though it would have given him more time to spend at the Wayne County farm he enjoyed so much.

He “celebrated” his 80th birthday in 1955 by following his typical daily routine — arriving at Memorial Hospital at 7:30 a.m. for that first of the day’s three surgeries, examining 50 or so patients at the hospital and at his downtown office in the Chafin Building, then making “rounds” again in the evening to see his hospitalized patients.

People, Hatfield insisted, “should keep on working.” And, that’s exactly what he did.