By Tim R. Massey

HQ 48 | SUMMER 2003

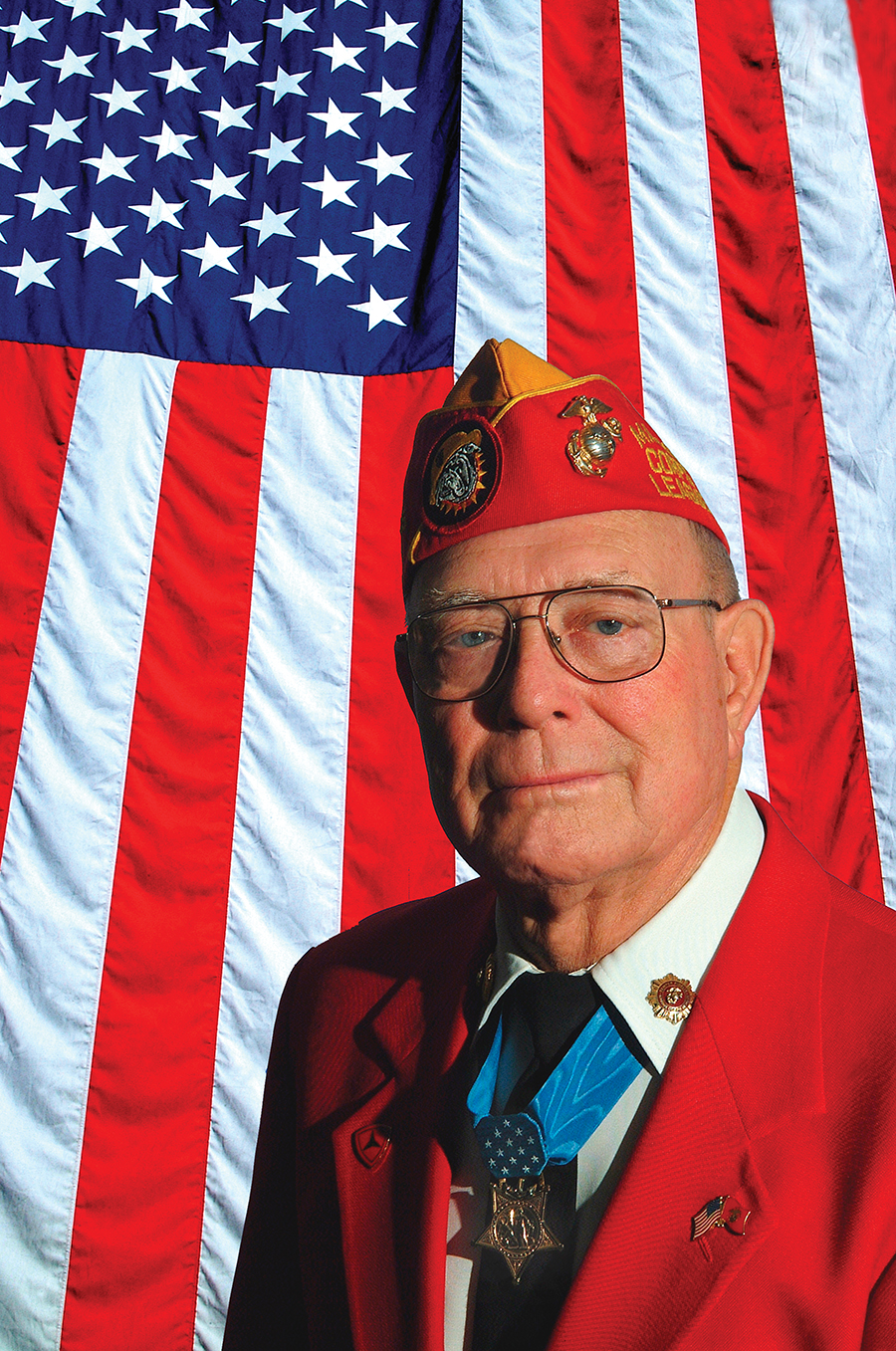

Standing only 5 feet 5 inches tall, Hershel “Woody” Williams couldn’t pass the minimum height requirements when he tried to enlist into the United States Marine Corps in 1942, but the 79-year-old World War II hero has long since demonstrated that he stands tall in the annals of America’s elite fighting force.

“It took them a while before they would take a runt,” Williams says, recalling his early rejection. “I always thought my lack of height was an advantage because I could dig a foxhole a lot faster than someone taller.”

Perhaps the Marines learned that a man’s stature has nothing to do with his height. They had twice rejected Audie Murphy because he was only 5 feet 9 inches tall, and the undersized Texan joined the Army and became the most decorated soldier in World War II. Williams proved himself in combat, too, earning the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroic actions during the bloody fighting on lwo Jima in February 1945.

The medal is awarded to those who show gallantry at the risk of their own life beyond the call of duty. Williams did that as a 21-year-old corporal for Headquarters, C company, 1st Battalion of the 34th Marine Division’s 21st Regiment. On Feb. 23, 1945 his battalion was involved in fierce fighting with the Japanese on the island of Iwo Jima. As many of his friends were being killed by Japanese forces that were holed up in underground concrete bunkers, Williams grabbed a 72-pound flamethrower and forged ahead alone to destroy the enemy. Covered by only four riflemen, he fought desperately for four hours under terrific enemy fire and succeeded in wiping out one enemy position after another.

Today, Williams is West Virginia’s only surviving recipient of America’s highest award for gallantry in battle. It’s an honor he holds as reverently now as he did when he received the medal from President Harry S. Truman on Oct. 5, 1945. “I still remember what the Commandant of the Marine Corps (General A.A. Vandergrift) told me,” Williams recalls. “He said the Medal didn’t belong to me; it belonged to the men who didn’t come home. He told me that I should never do anything to tarnish it. I have never forgotten that.”

Few have worn the Medal of Honor more proudly than Williams over the past 59 years. Since retiring from the Veteran’s Administration in 1979, he has championed the cause of patriotism across the country. He has participated in hundreds of parades and ceremonies, spoken to countless groups and worked tirelessly for veterans’ causes. He has served as chaplain of the Medal of Honor Society for the past 32 years, and recently headed an effort to build a new nursing home for veterans in Clarksburg.

“We need another nursing home for veterans,” Williams says. “The new one will have 120 beds, and they will be filled as soon as it opens. I would like to see another home built in the Huntington area.”

An active leader in the Marine Corps League’s Huntington detachment, Williams has participated in numerous memorials and funerals over the years. He also served as director of the West Virginia Veterans Home in Barboursville for a time before retiring in 1985.

“I don’t know of anyone who has been more accessible to the public and a better champion for veterans than Woody Williams,” says Ron Wroblewski of Ceredo, a former local Marine Corps League commander. “He is always there when you need him.”

Williams’ efforts have not gone unnoticed. He received West Virginia’s Distinguished Service Medal in 1965, and the Veterans Administration’s Vietnam Service Medal in 1967 for serving in the war zone as a civilian counselor. He has been inducted into Huntington’s Wall of Fame and has had a bridge on the West Virginia Turnpike name in his honor, as well as an armory in Fairmont and a playing field in Huntington.

Now, Wroblewski is heading an effort to have a U.S. Navy ship named for Williams. He has already delivered a petition making that request to the Secretary of the Navy signed by 20,000 state residents. Wroblewski is holding another petition with 23,000 signatures that he plans to hand deliver to the new Secretary of the Navy this year.

“I just think Woody deserves the honor,” says Wroblewski, a Vietnam veteran. “And, there are thousands of West Virginians who feel the same way.”

Williams says he is lending his support to the effort as a way of recognizing West Virginia veterans.

“This isn’t for me,” he says. “This is not going to be a Woody Williams ship, it’s going to be a West Virginia ship. It’s going to represent all the veterans of this state who have put their lives on the line for our country.

“No state has lost a higher percentage of its citizens in war than West Virginia. The state deserves the recognition for its contribution to preserving our freedom.”

An adept speaker who has taught Dale Carnegie courses, Williams often chooses freedom as the major topic of his speeches across the country.

“When I was born I was handed a jewel in my hand,” he says with a sudden burst of emotion. “The jewel was freedom. Someone had already earned it for me. That’s what America is all about.”

An ardent supporter of the United State’s war with Iraq, Williams says he is hopeful the Iraqi people will come to realize how priceless freedom is.

“I have said on many occasions that these people are going to wake up one day and realize that they are free,” he says. “That will be a great day for them, and the rest of the world.”

Williams says he is amazed by the firepower that U.S. military forces now possess.

“They have great capabilities,” he says. “They can see to fight at night, and they can kill the enemy from miles away. I can remember that we used to fire the Howitzer for effect so we could have an idea of where our rounds were landing.

“Now they are on target from 20 miles away because of global positioning. It’s just astounding what they are able to do. War is still terrible, but our forces are better equipped to fight than we were.”

Unlike the war in Iraq in which casualties were kept to a minimum, the battle for Iwo Jima was a bloodbath. Almost one third of the Marines who landed on the island became casualties – 5,931 killed and 17,372 wounded. Only 216 of the 22,000 Japanese on the volcanic island survived the onslaught.

Williams says he still doesn’t know why he was able to survive that day when so many shots were fired at him. He says his faith in God has helped sustain him since then. “God had a purpose for me that day,” he says. “I don’t know why I survived when many of my friends were killed on lwo Jima. I just know that my life was forever changed.”

A Sunday School teacher at Bethesda United Methodist Church since 1966, Williams has been married to the same woman, the former Ruby Meredith, for 58 years. He retired from his duties as a horse breeder in 1997, and turned the farm over to his grandson, Todd Graham.

The Congressional Medal of Honor has given him a front seat to many historic events over the past half-century. He has attended the inaugurations of every president since Truman, and has shaken most of their hands.

“I was most impressed with John F. Kennedy,” he says. “His inauguration speech was terrific. I remember how cold it was that day, but can still remember the command he had when he spoke to the audience.”

Still in relatively good health, Williams says he plans to continue speaking out for veterans and doing what he can to live up to the high standard expected from a Medal of Honor recipient.

“I’ll do what I can to make sure the medal is never tarnished,” he says with pride.