In part two of a three-part series, HQ profiles talented artists in the Huntington area.

By Tamar Alexia Fleishman

HQ 59 | AUTUMN 2006

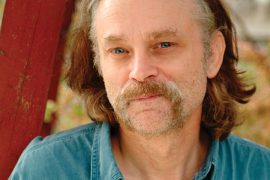

Bill Meadows is a man of this land, literally. A native of Greenup County, Bill spent his childhood digging up clay by the railroad tracks and making things. Now, a retired history teacher living in Huntington, he creates nationally acclaimed pottery and ceramics. Though his cousin was famous artist Clarence Carter — exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum — Meadows did not have an easy time growing up as an artist. “In Kentucky, doing anything creative in the public school system in the 1940s was not looked upon as what a person should do,” Meadows points out. Fortunately, because he came from an educated family, including his grandfather who was the local doctor, “My own parents did not look upon me with distaste,” he chuckles.

Meadows is creatively influenced by the primitive styles of 18th century pottery. “I’ve always been a student of history. I grew up around these forms. I remember my great-grandmother’s property in Porchman, on the Kentucky side. There was a building that was the former slave quarters. Inside, there was a huge assortment of antique pottery.

“Prior to 1900, anything preserved was in stoneware. But the introduction of glassware and canning at the beginning of the 20th century marked the demise of stoneware. Eventually, because pottery was no longer needed, many old treasures were lost or burned to fuel early trains.”

Meadows knows that there is a large demand from the public for handmade and primitive pottery, and has definite opinions on what a buyer should look for: “Craftsmanship and form, along with finish. Things that you could get for a dollar or two 30 years ago can go for $500 to $1,000.”

While he is aware of what is selling at any given time he says his first priority is to satisfy his own needs as to form.

Meadows is proud of the fact that a competition juror once complained that his style couldn’t be pinned down. “He told me, ‘You’re always changing,’ which I thought was quite good.”

Both his process and his personal taste contribute to the colors of Meadows’ creations. His pottery is available in both antique and newer colors. Meadows has just had a custom kiln built, and the temperatures it reaches will allow for a whole new spectrum of glazes. His fans have been crazy about his coppery-red pottery — it always sells well.

“Everything I know about this art form has been picked up and learned from my students. I was just going to be a friendly neighborhood history teacher. I took a job teaching in Barboursville and I had phenomenal students. I owe much of my success to them.”

Bill Meadows can be reached at (304) 525-1595.

Painter June Kilgore has had many dimensions to her career. This resident of Huntington has spent time both as a student and teacher, working on abstract and realism, all over the globe. Though she has Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from Marshall University, she has also studied at the Pratt Institute in New York, as well as Vanderbilt and Ohio Universities. Kilgore serves as Professor of Art Emeritus at Marshall, but has taught as far away as the University of Brazil. This global life experience has brought a sophistication to her art and the art of her students. “West Virginia is more than just Appalachian, primitive art. Some people come here just expecting to see that. But we have two major universities. We have so much to offer here,” she notes pointedly.

Though arthritis has slowed her travels somewhat, Kilgore is still an active painter. Her latest project is a new painting of still water, a quiet garden pond reflecting the sun. Her other projects have been more abstract, sometimes even turbulent. So, what provokes this artist to shift between two such different styles? “It’s the technique of it. My abstract work is more spiritual. It’s something I do rather than getting enamored with just the surface.”

Kilgore’s work is known for its bold use of color and color schemes. Part of this stems from a rebellion of the lack of color in design. “I was trained as a designer. I was conscious of color relationships. But I sensed that design was sterile and fixed. At Pratt, I had a teacher, George MacNeil, who pushed me. That’s the mark of a good teacher. I began to see color as tension points. Green makes red as red as it can be. It creates energy and dimension.” Kilgore explains that her use of color makes other techniques, such as the old “perspective” techniques (like drawing a tree at the top of the page to show distance) outmoded. “Color creates an openness.”

When she has traveled to distant lands, Kilgore is most influenced by the culture and natural environment, but not necessarily the local folk art. When visiting South America, she was affected by “their forests and how they’ve been abused.” Kilgore was fascinated by the mysterious valleys of Machupichu as well as the vegetation on conical mountains. “I painted the energy of a changing culture. You don’t know what they’re changing into, just that they’re changing.” She reflected this in her work by painting the volume of space. Her travels to Greece have also affected her work: she has painted the pond at Delphi, where the Oracles divined people’s futures.

Professor Kilgore has definite ideas on art education. “It takes a lot of openness to give a student room to try things without correcting him. You have to listen to them, respect their ideas.” Kilgore laments that many art teachers can only relate to those students who share their exact style. “They’ll just tell you to go along and find someone else to study.” She is adamant about the need for a solid academic education along with art studies. “They should learn some marketing! They should know how to call and make an appointment, not just show up at a gallery. I’d like to see them have to take some chemistry, especially the painters. But of course, they’re not going to make them do that,” she says wistfully.

When Kilgore is not busy with her art, she keeps closely involved with the community. “We live in a whole world, not just a region!” She spends time cooking for elderly people who can’t take care of themselves, as well as taking them to the doctor. “You have to be mindful of other people, not just buried in your own self.”