By James E. Casto

HQ 61 | SPRING 2007

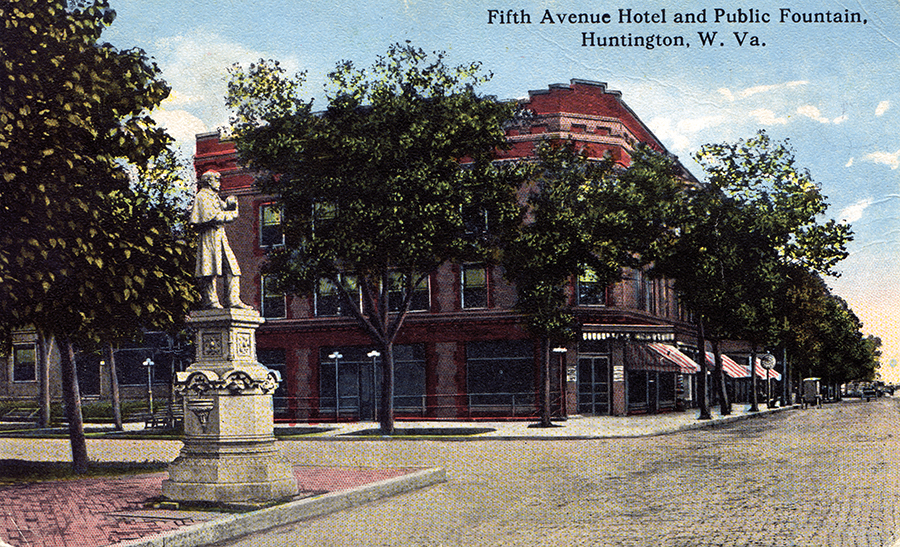

Huntington businessman Hansford Watts built the Fifth Avenue Hotel in 1910 on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street, originally the site of the city’s first church, the First Congregational Church.

The old church had been built in 1874, just two years after the city’s founding. In 1908, it was demolished and the property put up for sale when the church members decided to erect a new building two blocks to the west at Fifth Avenue and Seventh Street, where today’s congregation still worships.

From Huntington’s earliest years, the city’s role as a gateway to and from the rich West Virginia coalfields guaranteed that its hotels would do a brisk business. The traveling salesmen of that era – generally called “drummers” – routinely made Huntington their headquarters, venturing forth to surrounding communities and then returning to the city.

Catering to the needs of the drummers and others who came calling were a number of busy hotels, most of them clustered along Ninth Street. The Scrange, a two-story frame structure erected in 1872 on the southwest corner of Second Avenue and Ninth Street, is said to have been the city’s first hotel.

Among those following the Scrange were the Florentine, which opened in 1887 at Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street, and the Adelphi, located on the southeast corner of Sixth Avenue and Ninth Street. The site of the Adelphi would later be home to the Huntington Hotel. Just across Ninth Street from the Huntington was the Prichard Hotel. The Hotel Farr – later re-christened the Governor Cabell – welcomed travelers at Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street. And the city’s grandest hotel of all, the Frederick, was located only a few short steps away, just east of Ninth Street on Fourth Avenue.

The 100-room, three-story hotel that Hans Watts erected on the former church site at Fifth Avenue and Ninth Street boasted a handsome Edwardian design of brown brick with a number of decorative touches. Several shops were constructed on the first floor along the Ninth Street side of the building. The hotel’s main entrance was located at the building’s clipped northwest corner.

On the hotel’s Fifth Avenue side, an iron railing surrounded stone steps that provided access to a popular café that did business in the basement. In 1934, Morris Bailey moved his restaurant operation out of the hotel basement to a new location on Ninth Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues, where his Bailey’s Cafeteria would become one of the city’s best-known eateries.

“There was never anything fancy about the Fifth Avenue Hotel,” owner-manger Otis Hooper recalled in a newspaper interview with the Huntington Advertiser on his retirement in 1979.

Hooper worked at a number of hotels, both large and small, in his 50 years in the business. In 1956, he took over as manager of the Fifth Avenue Hotel after managing the Governor Cabell for several years. Later he and his wife, Lucy, purchased the hotel’s lease, making him both the owner and manager.

When the hotel first opened its doors, you could rent a room there for $1 a night – or $1.50 if you were the fussy sort who demanded your own private bathroom.

In the mid-1950s, when Hooper started as manager, the hotel’s room rates increased to $2.75 a night for a room with a bath and $1.75 for a room without a bath.

By 1979, when Hooper retired, a single room at the Fifth Avenue was $11 per night and there wasn’t much call for rooms without a private bath. The hotel offered no room service and there was no porter to carry your bags or run the elevator as in years past.

“We had an old bellboy here up to about four years ago,” Hooper told his newspaper interviewer. “But it got so people would keep him from carrying their bags because he was such an elderly fellow. Most of the time he’d sit down in the lobby and just fall asleep.”

By the 1970s, a big portion of the hotel’s dwindling business came from railroad train crews who bunked there between shifts.

The small hotel business “is a dying industry,” complained Hooper. “The hotels that were built 50 or 60 years ago just didn’t look ahead and see the need for parking. People today want the conveniences where they can drive in and out and have a place to eat.”

The Fifth Avenue Hotel struggled along for a few more years after Hooper retired but eventually closed. Today, the building is home to the Fifth Avenue Apartments, a housing project operated by the Cabell-Huntington Coalition for the Homeless.

The Case of the Missing Statue

In its earliest years of operation, guests at the Fifth Avenue Hotel who had rooms on the north side of the building could look out their windows and see a Civil War statue that stood across Fifth Avenue, in front of the Cabell County Public Library.

But the statue disappeared in 1915 and its fate remains a mystery.

Erected sometime in the mid-1890s, the cast iron statue of a Union soldier topped a public drinking fountain. In 1915, plans were announced to build a Confederate monument in Ritter Park and also move the Union soldier statue to a nearby site. The planned move riled local Union supporters. As a news article in the Huntington Advertiser reported, they felt the contrast between the elaborate Confederate monument and the small statue “would be discreditable to the Union cause.”

While the controversy swirled, the statue disappeared. Onlookers who saw it being loaded onto a wagon said they assumed it was bound for Ritter Park. But the old soldier never arrived there.

A subsequent article in the Advertiser speculated that the statue “was escorted to the junk heap” but the reporter could find no one willing to confirm that.