By James E. Casto

HQ 65 | SUMMER 2008

In a sense, Marshall University’s history can be divided into two parts – everything before 1961 and everything since.

It was in 1961 that the West Virginia Legislature approved a measure making a reality of Marshall’s longcherished dream of becoming a university. Moving up to university status laid the foundation for the spectacular growth that has unfolded at MU in recent years.

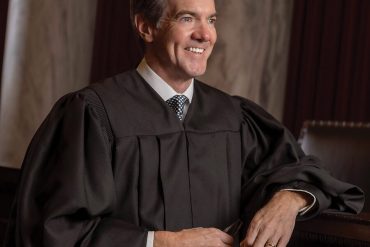

That historic victory was truly a team effort. But while the team had many players, it had only one coach – a determined President Stewart H. Smith, who literally worked night and day to win over reluctant lawmakers and convince them that Marshall merited the elevated status it was seeking.

Popular with students, faculty and the community, Smith served as Marshall’s president for more than two decades, longer than any of Marshall’s other presidents, before or since.

A native of York, Pennsylvania, Smith was a graduate of Gettysburg College, where he was an English major and president of the student body. He later earned a master’s degree from Columbia and a doctorate in education at Syracuse University. Before coming to Marshall, he taught English in the public schools, served as a high school principal and was a faculty member at Syracuse.

Smith was Dean of the Marshall Teachers College in the summer of 1946 when John D. Williams resigned as MU’s president. The West Virginia Board of Education, which then administered the state’s colleges, appointed Smith as interim president and at the end of the 1946-47 school year made that temporary appointment permanent.

During Smith’s 22 years as president, Marshall’s enrollment mushroomed from 3,500 students to 8,500, eight major buildings were erected and the school’s course offerings greatly expanded. But it was the attainment of university status that stands as his greatest achievement.

As early as 1927, the Marshall Alumni Association went on record favoring university status for Marshall College. No one took the suggestion seriously at the time, and the 1930s and 1940s with the Great Depression and World War II were hardly appropriate years for such an ambitious move. But with the war’s end and enactment of the GI Bill, returning veterans swelled Marshall’s enrollment and started people seriously talking about Marshall as a university.

In 1957, the North Central Association, the regional accrediting body for higher education, officially classified Marshall as a “university type institution.”

And in 1960, President Smith officially asked the state Board of Education to designate Marshall a university. Smith told the board: “Unbiased observers will be quick to recognize that it is only through the formal designation of Marshall as a university that the institution can occupy its vital role in the future of higher education in our state.”’

The board refused Smith’s request. But the next year, 1961, it reconsidered and recommended that the Legislature designate Marshall a university. That’s when the real fight began. The board’s recommendation touched off a no-holds-barred legislative battle between Marshall’s backers and supporters of West Virginia University, who were determined to preserve its status as the state’s only university.

A Morgantown newspaper editorially denounce Marshall’s “fever of empire building.” WVU’s immediate past president, Elvis Starr, then secretary of the Army, proclaimed that Marshall ought to dedicate itself to being “a first-rate college, rather a fourth-rate university.”

The intensity of the WVU supporters’ opposition, Smith later suggested, may have alienated some legislators “who might otherwise have opposed us.”

In his campus history, “Marshall University: An Institution Comes of Age,” Dr. Charles Moffat, the school’s legendary history professor, labels Smith “an articulate and indefatigable spokesman for the partisans of Marshall College.”

In that role, Smith logged literally thousands of miles on West Virginia’s highways and back roads, driving to every corner of the state to personally talk with legislators, newspaper editors and countless others he thought might be willing to aid Marshall’s cause.

Finally, when the smoke of battle cleared and the votes were counted, the State Senate approved the Marshall bill on February 16, 1961, and four days later the House of Delegates followed suit. Gov. W.W. Barron already had said he would sign the bill, thus it was clear Marshall had won.

At the time, some legislative insiders claimed one reason for Marshall’s victory was a bit of old-fashioned vote trading between lawmakers from the state’s northern and southern counties. Northern legislators working to gain passage of a constitutional amendment legalizing “liquor by the drink” in West Virginia are said to have agreed to support the Marshall bill in exchange for southern legislators’ agreeing to vote for the booze bill. At this point, nearly a half century later, it’s impossible to say just how big a factor this might have been in the passage of both measures.

When the news of the Legislature’s approval of the Marshall bill reached Huntington, it set off impromptu campus celebrations which saw students shouting with glee and waving copies of an extra published by The Parthenon, the campus newspaper. The newspaper’s huge headline: “We are now Marshall U.”

Here’s Smith’s own description of that day:

“I was in my office and didn’t know the Legislature had passed it. All at once we heard a terrific roar coming across campus. Hundreds of students came to Old Main. They called me out and asked me to make a speech. I couldn’t talk; I couldn’t form a word. I guess I finally said something. We had worked so hard. We had almost given up getting it through the Legislature. Then to have it happen was such an emotional shock.”

On March 2, Gov. Barron visited the campus to sign the bill into law, saying: “It is my sincere wish that Marshall’s future will be resplendent with new pride and progress.”

Indeed, “pride and progress” may be said to have been the hallmarks of Stewart Smith’s years as Marshall’s president. He retired in 1968. Rather than return to his native Pennsylvania, Smith chose to remain in Huntington. He died in 1982 at age 78.