Huntington’s steamboat heritage dates back to October 1811, when the first steamboat to appear on the Western rivers traveled past Guyandotte.

By Gerald Stuphin

HQ 75 | AUTUMN 2011

In late October 1811, the residents of Guyandotte, Va., were drawn to the banks of the Ohio River by the engine noise being made by the steamboat New Orleans, a type of boat never before seen on the Ohio River.

Looking more like an oceangoing vessel than a riverboat, the New Orleans, the first steamboat to appear west of the Appalachian Mountains, had been built in Pittsburgh by the same group of New York businessmen who, in 1807, built the North River Steamboat of Clermont (better known simply as the Clermont) to operate on the Hudson River. The Clermont would prove to be America’s first commercially successful steamboat.

This group, consisting of Robert Fulton, Robert Livingston and Nicholas Roosevelt (great-uncle of Teddy Roosevelt), was attempting to prove that a steamboat could operate against the notorious upstream current of the Western rivers to provide round-trip commerce.

Although the New Orleans encountered numerous obstacles, she was successful in reaching her namesake city in January 1812. This success set into motion the building of hundreds of what would become the uniquely American “Western river steamboat” and propelled our nation into its Industrial Revolution. (At that time, all rivers between the Appalachian Mountains and the Rocky Mountains were considered Western rivers. Today these rivers are more frequently referred to as the “inland rivers.”)

By the 1820s Guyandotte had developed into a thriving town where steamboats operating on the Ohio River and lower Guyandotte River made regular stops.

In 1834 Guyandotte was connected to the James River and Kanawha Turnpike and became an important stop on the upper Ohio River, transferring passengers and the U.S. Mail to steamboats running between Cincinnati and Guyandotte.

Steamboats and their impact on the Tri-State area during the 1850s may be best illustrated by the founding of the Guyandotte Navigation Company. This company built a series of six dams with locks up the Guyandotte River, from its mouth all the way to Logan. These projects were poorly constructed and required constant repairs, and in 1861 the Guyandotte locks and dams were destroyed by a massive flood, created by a storm that inundated the entire region.

At the start of the Civil War, the role of the steamboat in this area and across the nation quickly changed. Although many steamboats continued their commercial trades, many more were quickly converted to various types of gunboats or were converted into contracted troop/supply carriers.

Ironically, the steamboat that had been the agent of change and progress for Guyandotte would also be the agent that would carry troops to the town to destroy it. On Nov. 11, 1861, the steamboat Boston carried a detachment of Union troops up the Ohio River from Ceredo to expel a Confederate cavalry force there. In so doing, the Union troops also burned a large portion of the town. Guyandotte never fully recovered from this event.

At the end of the Civil War, the nation once again began to grow and continue its westward expansion. And once again, the steamboat played a significant part in the location, growth and development of a town; this one would become the city of Huntington.

In the late 1860s, Collis P. Huntington, president of the newly formed Chesapeake and Ohio Railway Company, was seeking a site for the western terminus of his railroad. He selected a location that had been previously incorporated by two brothers as Brownsville, Va. Understanding the importance of the depth of the Ohio River along a straight 10-mile stretch between Guyandotte and the mouth of the Big Sandy River, the brothers – Richard and Benjamin Brown – chose an area located around Fourth Street East for what they hoped would become a major port on the Ohio. The Brown brothers hired the famous French engineer Claudius Crozet to survey and layout Brownsville, which the General Assembly of the State of Virginia incorporated in 1831. However, it was not the right time or the right place, and Brownsville soon died.

Collis P. Huntington, like the Brown brothers, also recognized the importance of having the C&O Railroad connection with steamboats located within that 10-mile stretch along the Ohio River.

Huntington retained the services of Albert Laidley, a local lawyer, and requested him to acquire options to purchase 20 farms in Barboursville totaling 5,000 acres. When the time came to close the options on the land purchase, Emmons advised Huntington who had returned to New York that he would need $50,000 to make the first payment by March 1, 1870.

A delay in communications and a question about the type of payment needed led Emmons, accompanied by Judge H.J. Samuels, who was known by Portsmouth bankers, to take a steamboat to Portsmouth, Ohio, in search of a bank that would honor Huntington’s check to acquire the property before the option time expired – and before Huntington’s potential town slipped from his grasp.

At the first bank, the owner had no idea who Huntington was and refused to issue a check. But at the second bank, Emmons fared much better. The bank president was able to contact the New York bankers backing Huntington’s venture. However, at this point time was becoming a major concern, as the departure time for the steamboat Mountain Belle to travel to Huntington was approaching. Emmons appealed to the captain of the Mountain Belle to delay departure for an hour so that the cash would be on board when it left, and the captain reluctantly agreed. The Mountain Belle raced upriver to get the check to what would eventually become the city of Huntington before the option deadline passed.

Huntington’s new city was incorporated Feb. 27, 1871, by the State of West Virginia. The first two locomotives to run on this western terminus were brought from Parkersburg to Huntington on the Ohio River on Aug. 11, 1871, establishing a relationship between the river and the railroad that would continue to play a major role in the development of the city.

The riverfront was the hub of activities for the citizens of Huntington; steamboats provided travel for people, freight and the mail.

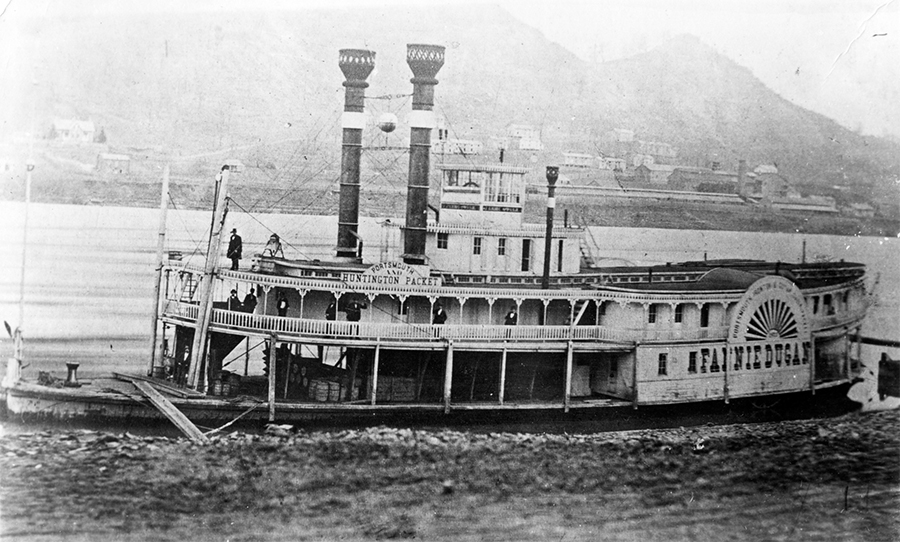

These activities are vividly related by Capt. Ellis C. Mace in his book River Steamboats and Steamboat Men. Speaking of his first river job, Capt. Mace said, “My brother, Carl Mace, was mate on the Fannie Dugan. He secured a position for me on the Fannie Dugan looking after the mail between Portsmouth, Ohio and Huntington, West Virginia. The mail was very heavy at times and was delivered to Wheelersburg, Franklin Furnace, Greenup, Ironton, Ashland, Catlettsburgh and Huntington. The Post Office at Huntington was between Ninth and Tenth Streets on the side next to the river … I was in charge of the mail until the Scioto Valley Railroad was extended to Ashland and the Fannie Dugan lost the mail contract.”

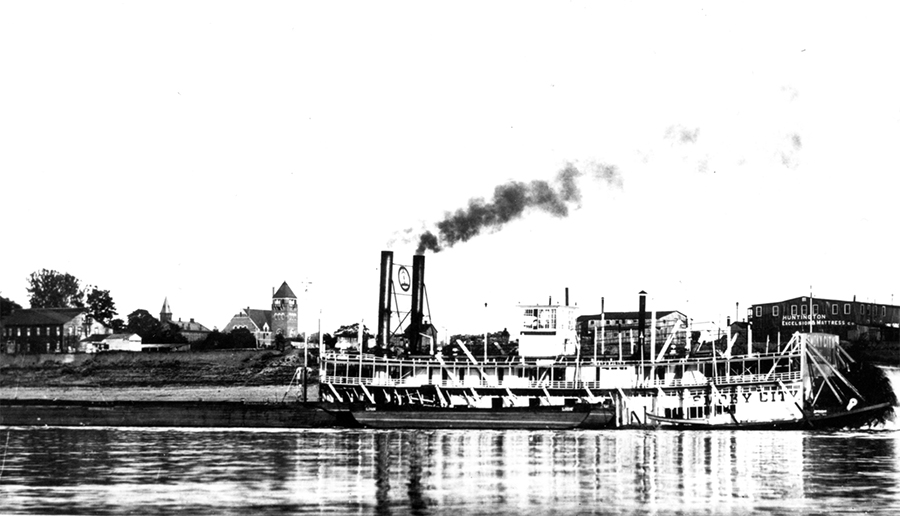

Huntington became a regular stop for the finest packet boats operating on the upper Ohio River. The two main landings were the public wharf at the foot of Tenth Street and the landing at the foot of Eighth Street. However, it wasn’t just packet boats – smaller boats designed to carry domestic mail, passengers and freight – that were passing in and out of Huntington; the riverfront was now the scene of large towboats pushing great fleets of coal, petroleum and sand and gravel barges to areas all over the inland waterways.

Huntington became the home of several towboat companies. One of the earliest was the Huntington and St. Louis Towboat Company, whose boats would tow iron, nails and other products of the Ohio Valley to St. Louis and return to Huntington with their barges loaded with grain. The barges were unloaded at the grain elevators at the foot of Seventh Street for shipment by the C&O Railway to points along the east coast.

Steam packet boats would continue to operate in and out of Huntington until Feb. 2, 1948, when the Greene Line steamer Evergreene ceased running between Huntington and Cincinnati.

While its waterways no longer carry the steamboats of yesteryear, Huntington remains one of the nation’s busiest inland river ports – and it continues to build on its very proud steamboat and river heritage.