The story of a Huntington woman who survived the most tragic maritime disaster of the 20th Century

By Joseph Platania

HQ 29 | AUTUMN 1997

Long ago when this century was young, a mighty ocean liner named the R.M.S. Titanic was launched in England for her maiden voyage to America. The luxury and comfort of her passenger accommodations exceeded those of any vessel of the day. Her size was greater than any other ship, the equipment, engines and integrity of her construction were the best money could buy.

A historical account states that “a deluxe cabin on B Deck cost the equivalent of $1,500 for two passengers and their servant.”

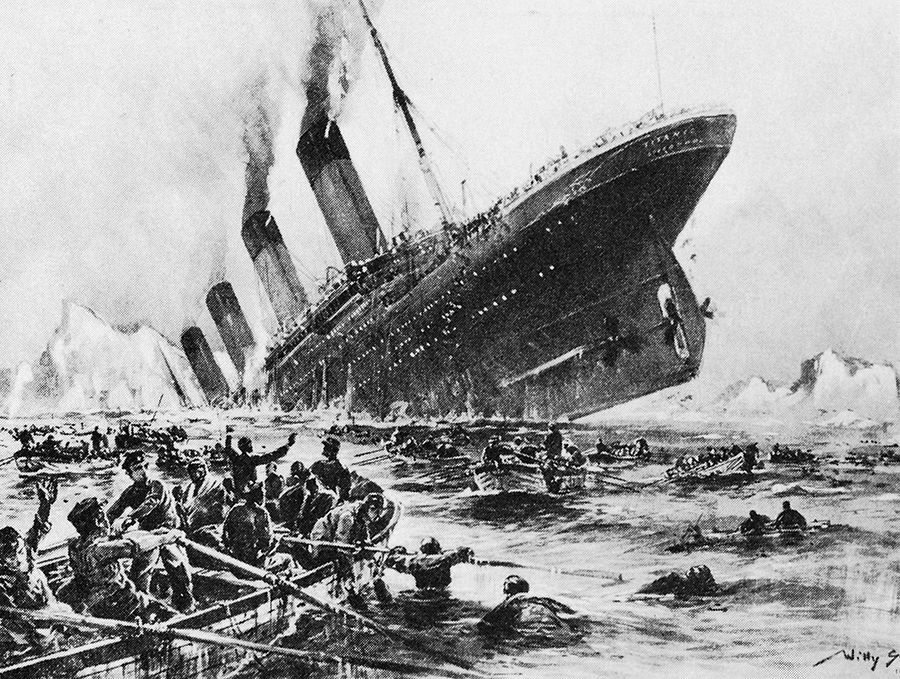

Then during the early morning hours of April 15, 1912, on the fifth day of her voyage, the Titanic struck an iceberg, broke in half and sank to the bottom of the ocean. The dead numbered 1,523, the survivors 711.

The Titanic saga often mentions such notable passengers as millionaire financier John Jacob Astor, Macy’s owner Isidor Straus and his wife, who died together linked arm-in-arm, and Brooklyn Bridge builder Washington Roebling. However, another less well-known story from that tragedy has as its central characters a young, newlywed Huntington woman, Eloise Hughes Smith, and her husband, Lucian.

On that fateful night more than 85 years ago, in the Titanic’s first class smoking room on A Deck, Lucian P. Smith struggled through the language problems of a bridge game with three Frenchmen. Smith, 24, had been married nine and a half weeks earlier, on February 8, in Huntington’s Central Christian Church in a ceremony that the newspaper described as “one of the most brilliant wedding functions that the city ever witnessed.” Now he was savoring the first Atlantic crossing of the Titanic as a fitting conclusion to a long honeymoon spent in Europe, Egypt and the Middle East. Lucian Smith was from Morgantown, W.Va. and came from a wealthy family whose holdings in the Pennsylvania coal fields meant that his future was secure.

Two decks below, his 18-year-old bride, Eloise, was asleep in her bedroom. The daughter of West Virginia Congressman James A. Hughes, of Huntington, she was not feeling well and had gone to bed early. A favorite ring Lucian had bought for her in Paris lay on a nightstand by the bed.

The bridge game upstairs continued. Other first class passengers joined the card players, sipping hot whiskey or hot lemonade to ward off the cold of the North Atlantic night. Then suddenly, a grinding noise stilled the room.

Several of the men jumped to their feet and walked out onto the deck. A moment later, Smith and others joined them outside in the bone-chilling air.

Just then a man cried out, “My God, we hit an iceberg!”

It was 11:40 p.m., April 14, 1912. The world’s largest and most luxurious liner afloat, called “unsinkable” by her builders and the press, was just two hours and 40 minutes away from being swallowed by the ocean in one of the worst maritime disasters in history.

The iceberg had torn a 300-foot gash in the Titanic’s starboard side. Immediately, water began flooding the first of the ship’s 16 watertight compartments. There were no bells or sirens, and no general alarm was sounded. But all over the Titanic, word spread that the “unbelievable” had happened.

In her bedroom on C Deck, Eloise Smith had been awakened by the ominous sound coming from far below in the ship. Suddenly, the lights snapped on and she saw her husband, Lucian, standing by the bed, smiling.

We are in the north and have struck an iceberg,” he said casually. “It does not amount to anything but will probably delay us a day getting into New York. However, as a matter of form, the captain has ordered all ladies on deck.”

Eloise dressed slowly but carefully in a heavy woolen dress, two coats, high top shoes and a knitted hood. Smith chattered away the whole time about landing in New York and taking the train south. He did not mention the iceberg again.

As they started for the deck, Eloise decided to go back for some jewelry.

But her husband drew the line, suggesting it might be more cautious not to bother with “trifles.” Compromising, Eloise picked up her favorite ring lying on the stand next to the bed and together, the couple headed up to the Boat Deck.

Many of the 2,234 passengers and crew aboard the Titanic did not realize, at first, their perilous position. According to a 1978 Huntington newspaper article, one of these passengers was Albert A. Stewart of New York – an uncle of Edith Reuschlein, wife of Huntington jeweler Charles F. Reuschlein. The article states that “the ebullient old gentleman knocked on a friend’s stateroom door and said, ‘Come out and amuse yourself.'”

Others had the same idea. One lady told another, “Oh, come and let’s see the berg – we have never seen one before.” Lucian and Eloise Smith sat quietly chatting in the ship’s gymnasium just off the Boat Deck. The first of the Titanic’s lifeboats began to take women and children on board.

In the 1986 book The Titanic: End of A Dream, “Mrs. Lucian Smith” is quoted as stating: “There was no commotion, no panic, and no one seemed interested in the unusual occurrence, many having crossed fifty and sixty times.”

Above their heads, several white distress rockets lit up the night sky with the flashes of their explosions. The people on the Boat Deck began to grasp that this was a crisis of major proportions. The joking and light banter ceased. It was time for parting.

Men helped their wives or other women into the lifeboats. Many refused to go, begging their husbands to join them. Arguments broke out and a number of women had to be made forcibly to get into the boats.

Eloise Smith saw the Titanic’s Capt. Edward J. Smith standing nearby with a megaphone and pleaded with him to allow her husband to go along. The old captain ignored her pleas and, lifting his megaphone, shouted, “Women and children first.”

Lucian Smith broke in, “Never mind, Captain, about that. I’ll see she gets in the boat.”

He turned to his wife and said very slowly, “I never expected to ask you to obey, but this is one time you must. It is only a matter of form to have women and children first. The ship is thoroughly equipped and everyone on her will be saved.”

Eloise asked him if he was being completely truthful. He replied with a firm, decisive “Yes.” The two newlyweds kissed and as the lifeboat dropped to the sea, Lucian called out from the deck, “Keep your hands in your pockets. It is very cold weather.”

An article reports that only 28 people occupied Lifeboat 6, the one into which Eloise was placed. The craft had room for 65, says the account. Across the icy water she could see her husband, along with hundreds of others, waving from the rail of the Boat Deck as her boat pulled away into the night. It was 1 a.m., April 15.

At 2:15 a.m., the Titanic, with her lights fully ablaze, was perpendicular in the water. From the third funnel, or smokestack, the ship stuck straight up in the air, its bow submerged and its three dripping propellers glistening in the starry darkness. Five minutes later, the vessel slid under the waves. As it descended to its final resting place more than two miles down, it broke apart amidship, halfway between the bow and the stern.

In Lifeboat 6, Eloise Smith was hurt that her husband had used a white lie to get her into the boat. For more than an hour she had watched – hoping for some sign of Lucian – as the luxury liner sank lower into the sea.

In a newspaper interview, Mrs. J.J. Brown, of Denver, said “There was a great sweep of water which went over us all.” She later was the subject of the movie “The Unsinkable Molly Brown.” She adds that “A great wave rose once and then fell and we knew that the steamer was gone. We could see as plainly as if it had been day,” said Mrs. Brown.

According to several accounts, Mrs. Brown and Lady Astor, wife of John Jacob Astor, were in Eloise’s lifeboat.

When the ship disappeared, it claimed 1,523 lives. Among them were millionaires John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim, Charles M. Hays, president of the Grand Trunk Railroad, Archie Butt, military aide to President Taft, and Henry Harris, a Broadway producer.

Lucian P. Smith also went down with the Titanic. Only three weeks before, he and his bride had been sightseeing in Egypt. Lucian had climbed to the top of a pyramid and, later, the couple rode a camel into the desert.

The 1978 newspaper article states that Eloise wrote home to her parents about their adventures in far-off lands. The article reports that: “In a letter now belonging to Mr. and Mrs. T.E. DeVilbiss, of 1111 11th St. In Huntington, she said: ‘Lucian is getting so anxious to get home and drive the car and fool around on the farm….We leave here Sunday….By boat to Brindisi (Italy), by rail to Nice and Monte Carlo, then to Paris and via Cherbourg either on the Lusitania or the new Titanic….I will love so much to tell my Sunday School class when I get home.'”

A local history states that Eloise spent her earliest years in Huntington, but much of her girlhood was spent in Washington, D.C. where her father was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Her mother was Belle Vinson, of the prominent and wealthy Vinson family of Wayne County. The history states that by the time of her debut in Huntington and Washington in January 1912, her dazzling beauty had caught the eye of a West Virginia University student named Lucian P. Smith. He had seen a photograph of her that a classmate from Wayne County had, says the history. It adds that Lucian came to Huntington with his classmate to meet the beautiful young woman. Soon after her debut, their engagement was announced.

Around dawn, after being adrift on the sea for hours, Eloise was rescued by the Cunard liner Carpathia, which steamed frantically 58 miles through the North Atlantic’s iceberg-choked water to help.

A week after her ordeal, nearly a thousand city residents jammed the C&O depot when Eloise arrived with her parents in Huntington by train. The 1978 newspaper article states that the crowd was so large that five policemen escorted her automobile from the station to her grandmother’s home in the Westmoreland part of town. In the weeks following the sinking and her rescue, Eloise gave interviews to New York and Washington newspapers as well as to the Huntington Herald-Dispatch recounting her experiences.

An article in the Richmond, Va. Newspaper of April 15, 1997 states that “Eloise failed to mention to reporters, if she knew it herself, that she was two months pregnant.”

On Sunday, May 12, 1912, in the Central Christian Church at Fifth Avenue and 12th Street, the same church where she had been married three months earlier, Eloise led an overflow crowd in a tearful memorial service for Lucian Smith. Among the hymns played at the service was “Nearer My God To Thee,” which scores of survivors, Eloise included, said was played by the Titanic’s orchestra during the ship’s final hours.

At almost the same time as the memorial service for Lucian Smith, congressional hearings began in Washington, D.C. to investigate the Titanic disaster.

Eloise Smith was one of the survivors who testified at the hearings and became something of a celebrity in the process. Because of the mourning clothes she wore, the press and Washington’s society dubbed her “the white widow,” states the 1978 newspaper article.

Later in the year after the sinking, a Huntington newspaper article reported that “Mrs. Smith was one of three Titanic brides to whom posthumous heirs were born.” She had a son, Lucian P. Smith, Jr., who was born on November 29, 1912.

The Richmond article quotes Taylor Vinson, a Washington lawyer who is a relative of Eloise Smith’s, who states “‘We used to say that Eloise was probably the only woman in the world who in just a year’s time made her debut, got engaged, married, survived the Titanic, became a widow and then a mother.'”

This might have been the end of Eloise Smith’s story of survival in one of history’s greatest maritime disasters. However, several years later there was a new chapter in her story, this time one involving romance and adventure on the high seas.

In October 1914, newspapers were filled with dispatches about the First World War then raging in Europe. That month war news was interrupted with a surprising new development in the Titanic saga. Mrs. Eloise Smith, 21, “widow of a hero of the Titanic,” had married another survivor of that catastrophe in a secret New York wedding. His name was Robert W. Daniel, then 29, president of his own banking company in New York.

Their romance, which began aboard the Carpathia on that tumultuous night, came to fruition on August 18, 1914 in “a secret wedding ceremony in New York’s Church of the Transfiguration.” The marriage was kept secret for two months because Daniel had to attend to pressing business matters in London.

At the time of the wedding announcement, Lucian, Jr. was nearing his second birthday.

Eloise’s new husband had lived to tell a remarkable tale of survival of his own. Daniel, a Richmond native, somehow managed to get free of the doomed vessel, swim in 30-degree water wearing little more than his underwear, find a lifeboat and eventually make it aboard the rescue ship Carpathia around dawn.

An article quotes from the statement of the Carpathia’s “ship’s surgeon” who reported four men who were pulled aboard, “one of whom apparently was Daniel.”

The lifeboat that he boarded, Daniel said, was the one containing Eloise Smith, states the article. It adds that Daniel said: “‘Her husband was lost and she seemed inconsolable.'”

There are conflicting reports about his rescue. In some accounts, Daniel makes no mention of being picked up by Lifeboat 6; nor does Eloise, in her narratives, mention seeing Daniel in her boat. However, the Virginian was saved from a watery grave. It came in the nick of time for him to be taken aboard the Carpathia.

The Richmond article reports that “Aboard the rescue ship, it seemed more than blankets and hot food warmed the newly acquainted Daniel and the attractive young woman from West Virginia.” The article quotes from a Huntington newspaper story that states: “Mr. Daniel was provided with a suit of clothes which fitted him the worst in the world and it is said that he was a ludicrous spectacle when he went to Mrs. Smith and presented himself, offering his good offices, and excusing the offer on the grounds that she was the only Southern woman on board.”

The Richmond newspaper of April 18, 1912 in banner headlines blared: “Robert Daniel Lands From Carpathia Half Dead and Incoherent.” The article adds that “The newspaper reported that Daniel left the ship carrying in his arms Mrs. Smith, handing the nearly faint woman to her congressman father.”

After recovering from his near death experience, Robert Daniel returned to his business activities.

The Richmond article explains that Daniel was “the son of a prominent lawyer, whose distinguished family” included “Edmund Randolph, the nation’s first attorney general, and a Civil War-era U.S. Supreme Court justice.”

At 27, Daniel was a successful international banker, frequently crossing the Atlantic on business, says the article. It adds that “He made his home at the Southern Club of Philadelphia.”

Several accounts state that Daniel was transporting a prized French bulldog with him to the U.S. when the Titanic when down.

At the time the ship sank, he was dressed only in his woolen sleepwear,” states the Richmond story, adding “his grandfather’s watch was hung around his neck for safekeeping.”

A Huntington newspaper article states that after Daniel’s marriage to Eloise, “the couple spent their honeymoon in England, sailing across the Atlantic just south of where the Titanic went down two years before.”

Bill McKelway, a staff reporter for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, states that Robert and Eloise Daniel lived in the lovely Rosemont section of Philadelphia.

Eloise and Daniel were divorced in 1923, nine years after their marriage.

In 1923, she married Capt. Lewis H. Cort, a member of a wealthy and prominent Huntington family, who was a World War I veteran.

An article in the Huntington newspaper of February 24, 1924 reports that Eloise “was drugged and robbed of $10,000 jewelry” while the Corts were asleep in their winter home in San Diego, California.

Capt. Cort died in 1927, at age 36, of his war-related injuries.

Eloise married her fourth husband, C.S. Wright, a state auditor of West Virginia, in 1929 and they lived in Charleston. The marriage ended in divorce several years later.

Following her divorce, Eloise resumed using her married name of Smith, the name of her only child, and she made her home in Huntington at the family residence at 1140 5th Avenue. She also “spent time in Uniontown, Pa. and in Florida,” states a local history. It adds that “she was active in politics and was a leader in Republican Party affairs.”

With her bright mind and gifted speaking ability, she toured West Virginia in several campaigns. Because she was a Titanic survivor whose husband had died when the liner sank, and as the daughter of a revered U.S. Congressman, Eloise was in great demand as a public speaker. She also campaigned for women’s right to vote prior to the enactment of the 19th Amendment in 1920. At one time, she held a position with the pension bureau in Washington.

A historical account reports that “It was said that a few months before her death, she had been gathering information and had considered writing a book on the sinking of the Titanic.”

But it was not to be. She died in early May 1940 after a few weeks illness in a Cincinnati sanitarium. When she was taken there, her condition was serious but not critical. Her death was attributed to a heart attack. She was 46. Survivors included her son, Lucian, her sister Tudelle VanSant, and a niece and nephew.

“Lucian Smith, Jr. was well known in Huntington,” states the local history, adding that his two daughters live in Florida.

Funeral services for Eloise Hughes Smith were held in Huntington on May 6, 1940. Burial was in Spring Hill Cemetery.

In the Richmond article, a niece, Jeanne Shasberger, who lives in Texas, said that Eloise “lived out her last ten years in the family home in Huntington. She was a wonderful, gracious person and always beautiful.”

Mrs. Cathy Gay, who lived in Florida and is one of Lucian Smith, Jr.’s daughters, told the Richmond paper: “No one in the family ever talked much about the Titanic. We dearly loved our father, but he would never talk about what happened.'”

On April 8, 1966, almost 54 years to the day Lucian Smith perished when the Titanic sank, his son and his family made headlines in another disaster on the high seas. The family was aboard the Viking Princess cruise ship when it caught fire in the Caribbean.

Gay adds that she nearly cries when she reads or hears about her grandmother and grandfather’s parting on the Titanic.

“‘It’s such a tragic love story when you think about the life they had ahead of them that was lost. It’s so sad. Our grandmother loved and missed her beloved, heroic Lucian until the day she died. My sister Betsy and I think that she never completely recovered emotionally from Lucian’s death or from witnessing the tragic deaths of the other 1,522 people on that ship. We believe she died at the age of 46 of a broken heart.'”