Huntington is revered as a quiet and secure community. But lurking in its past is a dark side with true stories of sensational crimes.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 30 | WINTER 1998

There is a wonder and fascination that crime has always elicited. Whether the offense makes front page headlines and the six o’clock news or is buried inside the newspaper in the “Police Blotter,” we are curious to know about it. This interest in wrongdoing usually is intensified when the crime, especially if it is sensational, takes place in the community in which we live.

As a medium-sized Ohio River city that once was the western terminus of the C&O Railway, Huntington has the reputation of being a sedate community with wide avenues, many churches and beautiful parks. Despite its conservative tradition, Huntington has had its share of sensational crimes during the city’s more than 125 year history. In fact, one of the most notorious acts of lawbreaking took place when Huntington was only four years old. This was the daring daylight robbery of the little Bank of Huntington by four members of the James-Younger Gang on September 6, 1875. In addition to this infamous bank heist, there are other criminal cases that stand out in the annals of the Jewel City’s history. Local historical accounts report an 1892 train robbery that left one man dead, several murders in the early 1900s, and the 1925 robbery of the Bank of Guyandotte.

Then in the summer of 1927 there began a 10 year period that had four sensational murder cases. When it came to crime, Huntington’s age of innocence had ended.

On Sunday, July 17, 1927, Bertha Long, of west Huntington, was to be married. Instead, early that morning she was shot dead by a jilted suitor. Also killed was a man who was with Miss Long at the time. The murderer later killed himself by placing a gun to his head.

With inch-high, front page headlines, The Herald-Dispatch for Monday morning, July 18, 1927, blared: “Scorned Rival Kills Woman, Fires On Man, Ends Own Life.”

The newspaper account reports that in an apparent love triangle of sorts, Bertha Long, 42, and John Turner, 50, of 1647 13th Avenue, were fatally shot by William Circle, 63, of 506 Piedmont Road.

The Saturday night before the shootings, Bertha Long and her fiance, Arthur McCreary, had been in downtown Huntington until late on the eve of their wedding. McCreary left Miss Long at the corner near her home at 2035 Adams Avenue and went to catch a streetcar. John Turner was waiting for her to return.

Turner had only recently met Miss Long and early that Sunday morning was sitting in his parked car waiting for her. Unknown to either of them, lurking behind a hedge and within Long’s front yard, “William Circle, armed with an automatic pistol, was waiting to end two lives,” reports a newspaper article.

Long paused when Turner confronted her. Then, Circle emerged from behind a hedge and thinking that his former sweetheart was about to enter Turner’s car, shouted at her. As she turned he fired two shots, one passing through her neck and the other penetrating her heart. Death was instantaneous. Aiming his gun at Turner, Circle then shot him three times, one bullet piercing his lung. Turner later died, but not before he had told police the identity of his assailant.

When police arrived at Circle’s residence to arrest him, they found the suspect laying dead on his front porch with a bullet through his head.

Long had been twice divorced and she and Circle had become acquainted three years before the shooting incident. A year before her murder, she had broken off their relationship. He had accused her of being a “gold digger” and had sent her letters threatening to kill her “unless she broke off with her recent companions and resumed her engagement to him,” says a story. Another article reports that Circle was accused by Long’s elderly parents of having entered their home some months before the murder/suicide and “menacing” their daughter with a knife, slashing and tearing her dress.

John Turner, the second victim of Circle’s pistol, was married and had a married daughter.

An article reports that Mrs. Turner thought that her husband was at work when he was shot three times early Sunday morning. Turner died the Monday night following the shooting incident.

A front page article states: “Bertha Long lay in her casket Sunday at her home…wearing her bridal dress.” The next day, as her parents mourned, Long was buried in Spring Hill Cemetery. The following day, her slayer, William Circle, also was buried in Spring Hill.

With these two burials in the same graveyard, one of Huntington’s strangest love triangles came to an end.

Shortly after midnight on August 8, 1929, Mrs. Elizabeth Wilson, age 36, wife of Burt Wilson, manager of the Guyan Creamery on Bridge Street in Guyandotte, shot and killed their 17-year-old daughter, Madeline, and then killed herself at their home in the affluent Park Hills section of the city.

An article reports that the daughter had apparently been shot at close range with a .32 caliber revolver as she slept. Mrs. Wilson then turned the handgun on herself, firing a bullet through her right temple.

That spring Madeline Wilson had graduated from Huntington High School. When her body was discovered, “she lay as if asleep in bed.” The body of her mother was “huddled at the side of the bed, the right side of her face pressed into the carpet,” states the account, adding that, “The gun was found gripped in Mrs. Wilson’s hands.”

The bodies of mother and daughter were discovered in the daughter’s bedroom by Mr. Wilson and a neighbor whom he had called after hearing the shots and was unable to open the bedroom door. Together, they had broken down the locked door and then called the police. An apparent suicide note was found in the house.

Mr. Wilson told police that his wife had been in ill health for many months and had often been unable to sleep. He theorized that shortly after they had gone to bed, Mrs. Wilson got up and got the gun they kept in their bedroom Wilson said that he was asleep and didn’t hear when his wife got out of bed. Evidence showed that in her wandering, Mrs. Wilson had gone into another bedroom and laid down for awhile on the bed. A short time later, she entered her daughter’s room, located across the hall from the parents’ bedroom. She then used the gun in the fatal shootings.

An article states that “a nervous breakdown” suffered by Mrs. Wilson was held to be the cause of the murder/suicide. The story adds that “she was in a fit of despondency as a result of ill health.”

As tragic as this murder/suicide involving family members was, it was followed several years later by a similar case.

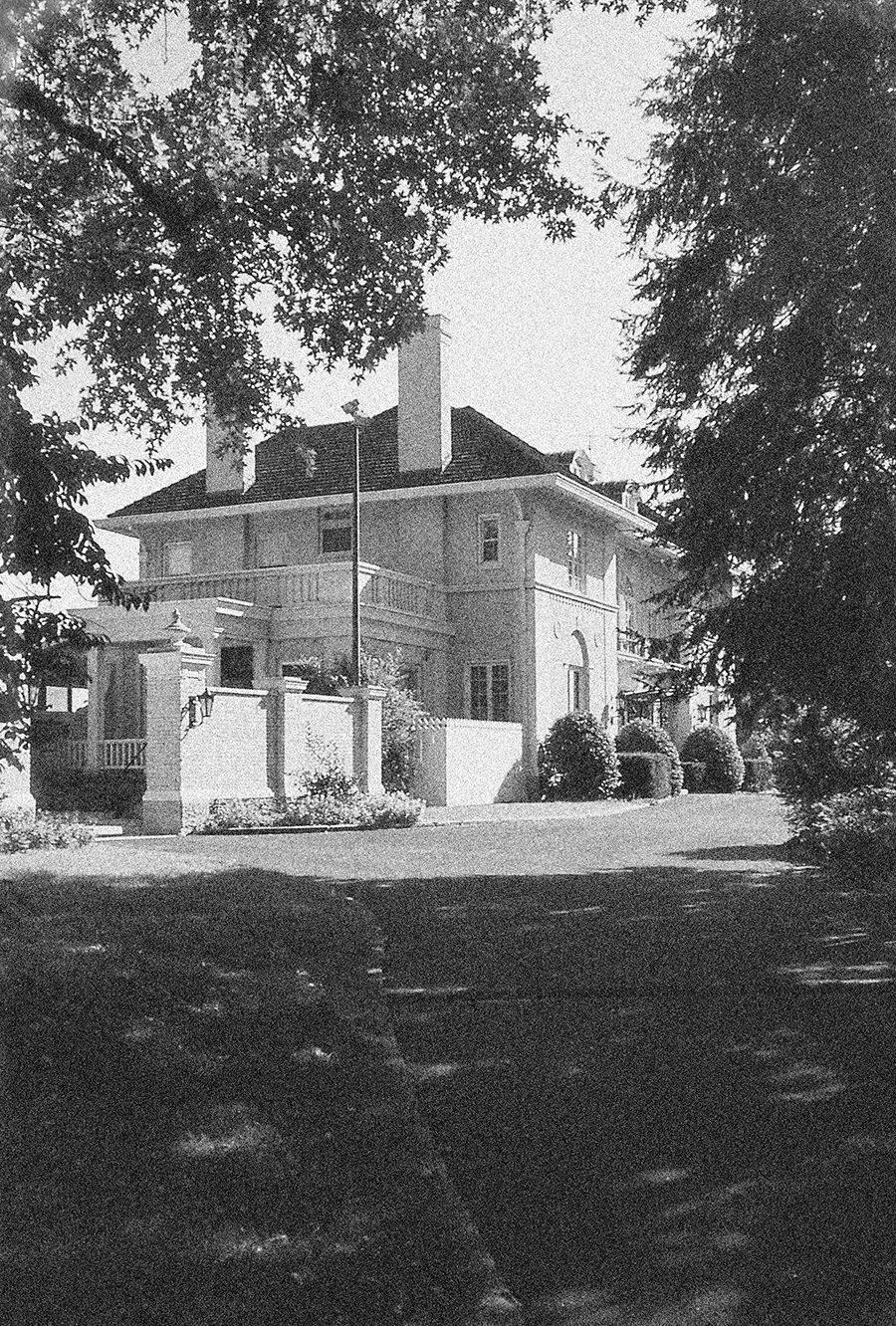

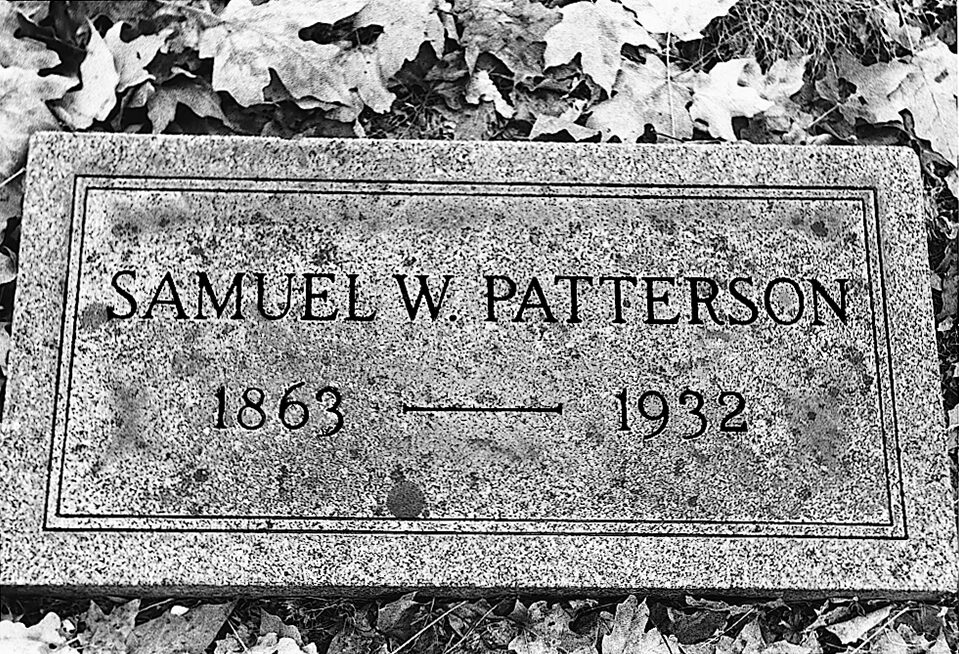

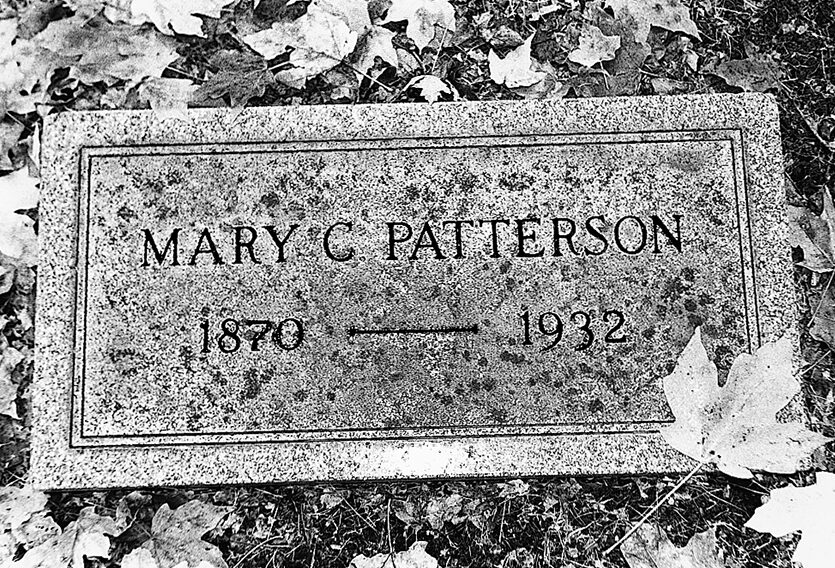

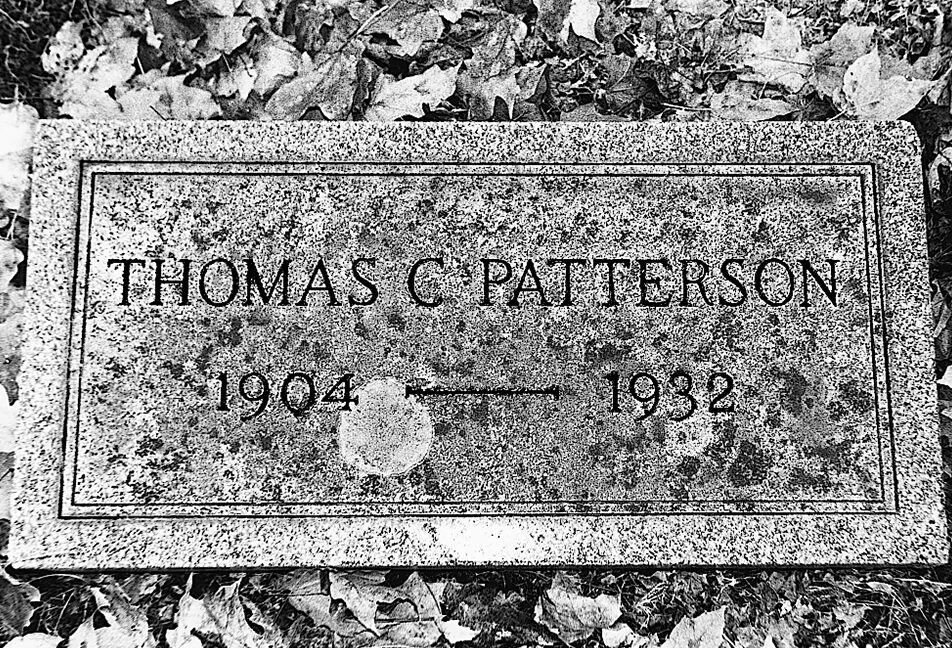

Tuesday morning, October 25, 1932, a few weeks before the presidential election that would send FDR to the White House in the depths of the Depression, Huntington residents awoke to read front page headlines about the murders of coal executive S.W. Patterson and his wife at the hands of their 27-year-old son, Thomas C. Patterson, who then took his own life. The annihilation of this prominent Huntington family occurred at about 11 p.m. Sunday, “in the palatial Patterson residence on Staunton Road,” in the Highlawn section of town. Evidence at the scene of the double murder/suicide showed that Mrs. Patterson had been shot twice in the head as she listened to a radio program in the living room. Mr. Patterson was killed as he sat reading in his study at the other end of the hall. He was shot once in the head and there was a gash in his forehead, presumably from the blow of a hatchet that was later found in his son’s room.

After the murders of his parents, the son, Thomas, locked himself in his bedroom where he slashed his wrists with a large butcher knife and bled to death. An article reports that a note found in his bathroom read: “`I have been murdered by a ghost – a devil. I wish to be cremated. Homicidal maniac. I’m sorry.’ The note was signed by the young man’s initials – T.C.P.,” says the story.

The bathroom was described as “a shambles” with blood-smeared walls where the younger Patterson had tried to write on the wall with his own blood and with hatchet marks where he had hacked the wall. The bathtub and basin also were smeared with blood.

Inside the son’s room and bathroom were found a Colt revolver, two hatchets and a large butcher knife.

An article states that Thomas Patterson was “a writer and poet” who had graduated from Yale University in 1926 and had returned to Huntington to live. After his graduation, Patterson had pursued a literary career. It adds that Patterson had had a slim volume of poetry privately published and he had completed a biography of Edgar Allan Poe that was in the hands of a publisher.

The official investigation of the double murder/suicide case revealed that the younger Patterson had suffered from a mental condition for several years and had been under the care of a Baltimore psychiatrist who had recommended that he be institutionalized.

The Pattersons had moved to Huntington from Williamson, W.Va. in 1923. S.W. Patterson was in business with his brother, Col. G.S. Patterson, of Huntington, in the Sycamore Coal Company.

An article reports that the inability of servants to enter the Patterson home on Monday morning led to the gruesome discovery of the bodies by Col. Patterson and his wife.

Following a joint funeral service on October 26, 1932, the S.W. Patterson family were buried in three identical gray caskets in Woodmere Cemetery.

Almost exactly four years after the Patterson double murder/suicide case, Huntington was rocked by news of the murder of one of the city’s most socially prominent women in her home on “Millionaires’ Row,” on October 17, 1936.

Mrs. Juliette B. Enslow, age 63 and a wealthy widow, was found dead in her bedroom on the second floor of the Enslow mansion at 1307 Third Avenue at 8:30 a.m., Saturday, October 17.

By her marriage, Juliette Buffington Enslow was a member of two of Huntington’s “first families.” Her father was Peter Cline Buffington, the city’s first mayor, and she was the granddaughter of William Buffington, Cabell County’s first surveyor. Her great-grandfather, Thomas Buffington, was an early settler in the county.

After the death of her first husband, Charles Baldwin, of Athens, Georgia, Juliette married Frank B. Enslow. Regarded as one of the most influential men in West Virginia, Frank Bliss Enslow became a notable figure in business and civic affairs during Huntington’s early decades. A lawyer by profession, Enslow was a director and, later, president of the Huntington National Bank. Prior to his death in 1917, he spent most of his career engaged in West Virginia’s oil and gas development. He also owned extensive properties in Huntington.

Enslow’s many business interests made him an extremely wealthy man in the era before income taxes. During the 1890s he used some of his wealth to build one of the city’s most elegant homes.

With 27 rooms, marble fireplaces, Tiffany chandeliers, and stained glass windows, the Enlsow home was a center of Huntington social life in the early 1900s. Parties frequently were given in the mansion for the city’s affluent citizens.

Frank Enslow’s first wife, Julia, was a niece of Juliette Buffington and they had one son, Frank Enslow, Jr. before Julia died in 1897. He then married Juliette in 1901 and they had a daughter, Dorothy.

Mrs. Enslow had a son from her first marriage, Charles B. Baldwin, who was 41 at the time of her death.

At some time between 10:30 Friday night and 8:30 Saturday morning, October 17, Mrs. Enslow was “stabbed in the head with a finely pointed instrument, beat about the face and body and possibly strangled with a towel found loosely knotted about her throat,” states a newspaper account. The time of death was placed between 2 and 4 a.m.

After an investigation, “valuable diamond rings and a diamond-studded wristwatch that Mrs. Enslow usually wore to bed at night,” were missing. The wristwatch later was found in a drawer in her room.

In addition to the wealthy widow, the mansion was occupied by her son, Charles Baldwin, and Lizzie E. Bricker, the housekeeper and companion. There also was a staff of servants. An article states that “on the evening of Friday, Oct. 16, Baldwin and three friends had played contract bridge in the Enslow drawing room.”

After a billfold belonging to Mrs. Enslow was found on the driveway by the chauffeur when he came to work early Saturday morning, the housekeeper rushed up to her employer’s suite of rooms where she discovered her body. She then called the police.

An article describes the brutal nature of the crime: “Bruises about the face and mouth (were)…taken as an indication that (Mrs. Enslow) had been choked. Five wounds, inflicted by a sharp instrument, thought to have been an ice pick, were found on her forehead, and there were four similar wounds on one of her hands,” says the story.

There was an absence of fingerprints or marks on the window sill of the Enslow mansion or on the wooden posts supporting the veranda to indicate that anyone had entered or left the home by way of the veranda.

Police soon ruled out burglary as the motive and worked on the assumption that it had been an “inside job.”

To support this theory, there was the fact that the billfold found by the chauffeur was dry, although it had rained the preceding evening, indicating that this crucial piece of evidence had been planted.

Mrs. Juliette B. Enslow’s funeral was held at her home with the pastor of the Trinity Episcopal Church officiating. Burial was in Spring Hill Cemetery.

On October 27, 1936, 10 days after her murder, Enslow’s son, Charles B. Baldwin, “a former practicing lawyer,” was arraigned on a charge of homicide. Court records show that on February 18, 1937, Baldwin was formally indicted by a grand jury for the Enslow murder. After a jury trial in common pleas court, he was found “not guilty” of the murder charge on March 25, 1937. This sensational murder case remained dormant until almost three years later.

On February 22, 1940, a new development in the Enslow case was reported by The Herald-Dispatch in front page headlines. This was the discovery of one of the two valuable diamond rings that had disappeared in connection with the murder. The ring was found by a city street department employee in a “catch basin” in the alley behind the Enslow home and a short distance east of the rear entrance to the property.

Many Huntingtonians were skeptical that the diamond ring had remained in the sewer lines for four years and had not been washed away by the 1937 flood. The ring was described as a large diamond solitaire in a platinum setting with a black onyx mounting.

Despite the discovery of the missing gem, there is no indications that this baffling case was reopened by the police. The Enlsow mansion later was sold and for many years, it was the site of the Steele Funeral Home. The building now is gone, the victim of fire.

More than 60 years later, mystery still surrounds the brutal bedroom murder of Mrs. Juliette B. Enslow.