A candid conversation with the C.E.O. of the region’s largest company regarding people, profits and the future.

HQ 31 | SPRING 1998

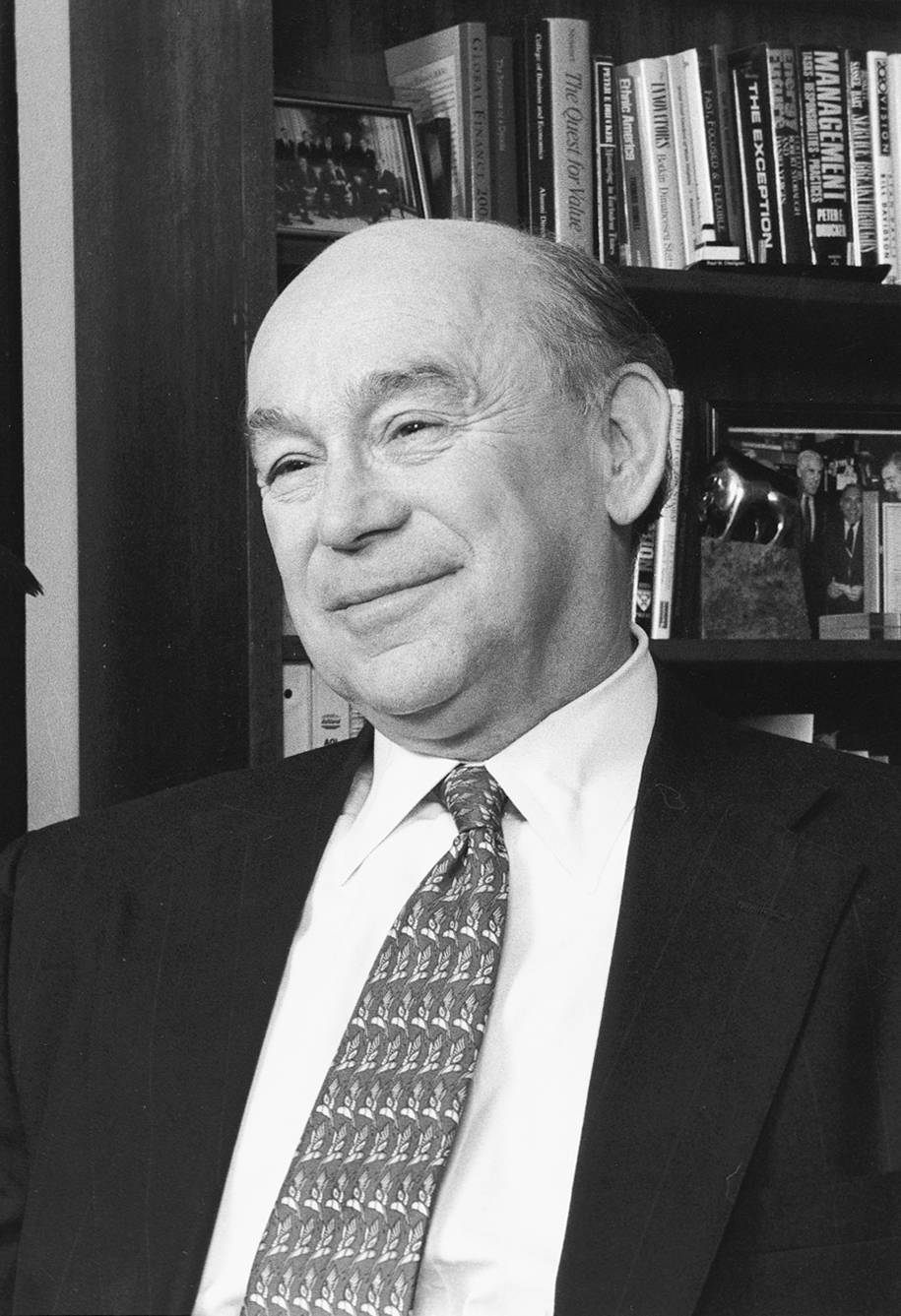

Paul W. Chellgren lives by a very simple philosophy: work hard and play hard. As only the fifth chairman and chief executive officer of Ashland Incorporated, a Fortune 500 company and the Tri-State’s largest employer, Chellgren balances a grueling work schedule with an intense dedication to exercise and competitive running. A typical day for the 55-year-old power broker might include high-level meetings in the morning, flights on the company jet to oversee operations in Lexington, Louisville, Columbus or Atlanta, a late afternoon workout in the company weight room where he can bench press upwards of 250 pounds, more hours logged at the office through the early evening and finally, some valuable down time with his wife and three children at night.

Chellgren first joined the company in the early 1970s where he took summer jobs sweeping floors and cleaning bathrooms. He then earned his B.S. from the University of Kentucky, a M.B.A. from Harvard University and a D.D.E. from Oxford University, where he was a standout rugby player. He worked in London and at the Pentagon before returning to Ashland as an executive assistant. The ambitious, young executive then began his ascent of the company ladder culminating with his election as chief executive officer on October 1, 1996, and chairman of the board on January 30, 1997. His leadership was tested immediately when Providence Capital, a New York investment firm, proposed nominating three directors to Ashland’s board. The power play by Providence Capital sent a clear message that Wall Street had not been pleased with the company’s past performance. Chellgren spent his first weeks on the job meeting with investors and announced plans aimed at improving profitability and shareholder returns. A landmark deal between Ashland Petroleum and Marathon Oil was completed in January and created the nation’s fourth largest oil refinery. The newly formed company was named Marathon Ashland Petroleum LLC with Marathon owning 62 percent of the new entity and Ashland owning 38 percent. Providence Capital ultimately withdrew its nominations to Ashland’s board. Chellgren’s strategy had paid off. The quarter ending December 31, 1997, saw Ashland post a 44 percent increase in earnings. However, the deal and the resulting profits have not come without a price. Nearly 150 local Ashland employees have lost their jobs and another 150 have been transferred.

Chellgren sat down with Huntington Quarterly Editor John H. Houvouras on a cool January morning at his office in the Ashland Inc. building. The two discussed a number of topics including work ethic, mentors, the environment, the Tri-State, sports, movies, greed and how to take a knock and how to give one, whether in business or in life.

HQ: What does a typical week entail for Paul Chellgren?

CHELLGREN: It includes a lot of travel. I travel almost every day including weekends. Frequently, they are day trips. This week was a good example. Monday we were in St. Louis, Tuesday in Lexington, on Wednesday I was in Findlay, Ohio. Yesterday, I happened to be here and today I happen to be here. Two days in a row of not traveling is a bit unusual. We’re going out for meetings with our people, meetings with our joint venture partners, board meetings, customers and suppliers. Increasingly, since I’ve become chairman, I’m involved with the governance of more organizations.

HQ: What kind of hours do you put in?

CHELLGREN: Well, they’re long days. Sometimes I won’t get home until 11 or 12 o’clock at night after traveling. We start work at 8 o’clock in the morning.

HQ: And your wife hasn’t left you?

CHELLGREN: [Smiles] No, no. She’s put up with it since the very beginning. I’ve traveled all my business career.

HQ: Since joining Ashland in 1974, what have been some of the highs and lows you’ve seen in the company?

CHELLGREN: You know, that’s an interesting question. In some ways, you’d think that they (the highs and lows) would be discreet, but they’re not. The highs and lows have occurred simultaneously. An example is the situation right now. There is an enormous high and exhilaration about finally accomplishing this joint venture with Marathon Oil – the scale of the project, the positives, the bright future we have. And at the same time, we have some lows. We’re going through some social costs, terminations, some people transferring, some real impact on our local community and that’s clearly a low. Looking back, certainly some of the lows were things such as the management transition we went through in 1981. Another low was the Belzberg issue in 1986. Another low was the whole Kenova litigation era – a very awkward and difficult time at so many levels of the corporation and for the community as well. There were some other lows. Disappointments in certain business performance. The highs have dramatically outweighed the lows. The highs would be accomplishing certain plans, acquisitions, joint ventures. Fun, exciting things. Also seeing people grow and seeing the organization grow. That, in some ways, is the greatest part of being the manager of a large, complex enterprise.

“My job is terribly important. You’re responsible for people’s lives, for pensioners, for the stakeholders in this enterprise. And that’s a very real burden.”

HQ: What are some of the reasons you were able to climb the company ladder so successfully?

CHELLGREN: Perhaps I’m not the best person to ask. [Laughs] Perhaps you should ask some of the people who were judging my performance along the way. But clearly hard work, sacrifice, getting involved with the organization, understanding it at the most fundamental level. I think some people don’t understand the basic mission of an institution. And if you really aspire to be at the highest level of that institution, it helps to understand it and try to be involved in the basic mission. I think some people are comfortable in being on the peripheral side of things and they may do very well. But if you aspire to the most senior level you need to be very much involved in the basic, fundamental mission. In our case, it’s providing the goods and services line. Operating profit centers. That’s what I’ve always aspired to do, run operations. So, you need to get involved in the guts, the heart of what really drives an enterprise. That’s true with any enterprise.

HQ: How does a young man from Ashland make his way to Harvard and Oxford?

CHELLGREN: Well, you fill out application forms and mail them in and then they accept you or they don’t. [Smiles]

HQ: Was working for the Pentagon as exciting as it sounds?

CHELLGREN: Yes. It was an extraordinary time at the Office of the Secretary of Defense in the Pentagon. I joined in the summer of 1968. At the time, McNamara was leaving and Clark Clifford was coming in. And, of course, there was the election that year. The year 1968, in Washington, was a year that could hardly be believed. The Martin Luther King assassination, the Bobby Kennedy assassination, protests at the Pentagon, the Vietnam War era…it was an extraordinary time. I was there when the Administration changed. Nixon came in in January of 1969, appointed his own political appointees at the Office of the Secretary and Military Services. If you’ve ever read David Halberstam’s book, “The Best and the Brightest,” that was the era of young people, many of them, frankly, with Harvard connections. There were some of the finest, most talented people in the country there at the Pentagon at that time and it was interesting to observe and participate in that. Some of the people from that era continue to be my very closest, personal friends.

HQ: Who are some of the people you have most respected and admired in your life?

CHELLGREN: Certainly the ones I’ve had personal contact with, people who have been personal mentors. A few special teachers, my debating coach in college, my adviser at Harvard Business School. The man I worked for at Office of the Secretary of Defense, Robert C. Moot, had an extraordinary ability in a very non-threatening way to effect change in one of the biggest enterprises the world has ever seen. Some of the bosses I’ve had, especially at Ashland: Orin Adkins, my first boss here, had a big influence on me. Ed Von Doersten, president of the chemical company. And especially John Hall, who I worked for for 15 years. He has been like an older brother to me. His influence on my career has been very strong. Obviously my father. He would be prominent in terms of influence when I was younger and even still today. We talk often not only about our family but business judgment issues as well.

HQ: Ashland has often come under fire for its lack of concern for the environment. How do you answer your critics?

CHELLGREN: There are always critics and we’re in businesses that have environmental issues and exposures which you work very hard to minimize, but they are something you need to manage everyday. I know here in the Tri-State we’ve had some particular criticism, but from an overall corporate point of view much of that criticism is unfair and unbalanced. People don’t understand the totality of this company. I think people, unfortunately, tend to focus on one physical facility – the Cattletsburg refinery. That is not the totality of Ashland Incorporated. This is an enterprise of large scale with hundreds of physical facilities, tens of thousands of employees, many different lines of business. And if you look at our overall record in this area, I think we stack up pretty well. That’s not to say we haven’t made mistakes. There’s no doubt that in the early 1980s, when we were starting up the RCC unit and the MRS unit at the Cattletsburg refinery there were some problems that, in retrospect, should not have occurred. There were some engineering problems, there were some operating problems. There were some calcium carbonate releases and those were unfortunate. We also weren’t as sensitive to the implications of those releases as we should have been.

HQ: Do you think the world will still rely on fossil fuels by the middle of the 21st Century?

CHELLGREN: That’s a little over 50 years from now and I think the clear answer is yes. I think the world will rely on fossil fuels in many forms – coal, natural gas, liquid petroleum fuels, plastics and on and on. To some extent it’s a question of what the alternatives are. What are we going to rely on? Almost 60 percent of America’s electricity is produced by coal. Coal-fired power plants can last half a century or longer. Are we going to be building nuclear power plants in this country again? I don’t believe so. I think the last nuclear plant ordered in this country was before Three Mile Island. Now that’s not to say there aren’t going to be enormous advances particularly in ways to fuel transportation. Hybrid vehicles, more natural gas for fleets, some fuel cells, much more advanced batteries, electrical vehicles. But again, people say, ‘Well, the electric car is non-polluting’ and I sometimes ask them, ‘Where does the electricity come from?’ [Smiles] So I think the answer is clearly yes – we will rely on fossil fuels, but the mix of energy sources are going to be more complex because of the advances in technology today.

HQ: Will solar energy make it into that mix and, if so, by when?

CHELLGREN: There is some solar now. It will play a bigger role in some areas but solar will be used to generate electricity. But again to produce the materials – solar collection panels and the like – it takes energy to produce the materials to collect and store and transport it as well. There are no simple solutions. There’s very little opportunity for more hydro and hydro plays a significant role in this country. The nuclear plants are actually starting to go offline, and will do so at an increasing rate.

HQ: You have lived in this area for most of your life. What do you see as the region’s greatest strengths and weaknesses?

CHELLGREN: This region has enormous strengths including the stability and quality of the workforce, the fundamental values of the people, the comfortable lifestyle. So you are dealing with an area that has a lot of advantages. It has many challenges and shortcomings as well that are reflected in the fact that as an SMSA (Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area) over the last 10 to 20 to 30 years, it’s been stable or shrinking in comparison with other more rapidly growing metropolitan areas. What are the reasons for that? There are issues of transportation such as airport access, there are issues of wage rates, there are issues of education, there are issues of affordable housing, there are issues of buildable land, issues of entrepreneurial activity. But we’ve been well served by having our headquarters here for nearly 75 years. The Tri-State has been a good place for people to grow up, live, work and flourish.

HQ: What are the five most important things in your life?

CHELLGREN: Clearly family, that is my wife and three children, my bothers, sisters and my parents – we’re all quite close. Last night, I was here working until after 10 o’clock and happened to talk to two of my three sisters about one thing or another. My job is terribly important. You’re responsible for people’s lives, for pensioners, for the stakeholders in this enterprise. And that’s a very real burden. Another important thing in my life is exercise. Community activities, or a sense of service or giving back, are very important. That’s something this company has always encouraged employees to do and will continue to encourage people to do if I have anything to do with it.

HQ: What are your favorite books of all time?

CHELLGREN: I read a lot of history. Biographies of historical figures, the history of the great societies and cultures – the Egyptian culture and the Greek culture, the Roman culture. A lot of European history. I spent time in England, love England and have close ties there. I love to read about English historical figures, kings and political figures. I also read a lot about art. Books on art and art history.

HQ: What are your favorite films of all time?

CHELLGREN: In some ways Dr. Zhivago. Your readers will remember Omar Shariff and Julie Christie. The whole Godfather series was great. The Star Wars trilogy was great fun and would certainly be on my short list.

HQ: Of all the sports you’ve tried in your life, what do you enjoy the most?

CHELLGREN: I’ve played a lot of sports and really like to exercise. I didn’t play any high school athletics but I played a lot of intramurals in college and then I went to graduate school and I started playing rugby. After I started rugby, I began lifting weights to get bigger and stronger. I played a lot of rugby in England and then returned to the states and played for a lot of teams here. I’ve played rugby with first-class clubs for 15 years. I really enjoyed it. It’s a great team sport, a very rough sport. You’ve got to be able to take a knock, and give one, but that’s sort of what life is like. [Smiles] In the business world, if you can’t take a knock and hopefully give one back better, you’ve got trouble. I stopped playing rugby when I was about 37 years old. When your teammates are calling you “sir,” and you have a mortgage and children, you worry about getting hurt and not healing. [Laughs] I still run competitively. In fact this past year I had 10 races – 5Ks, 10Ks. I like to do that and really enjoy it. I’ve played around with weights for a long time and do it reasonably seriously. Another sport I love, but don’t do nearly enough, is skiing.

HQ: Why do so many successful business people come out of a sports background?

CHELLGREN: I think the answer can be found at two levels. First, team sports build a sense of teamwork and leadership. And much of what you do in a corporation or institution is leading a team. The same kind of skills that make you a captain of a sports team are the same kind of leadership skills, coalescing skills, sense of responsibility, understanding group dynamics, that are necessary in running an organization. Second, whether it is a team sport or an individual sport, it is question of preparation, competition, striving for excellence, making sacrifices and pushing the edge of performance. You can’t just go through the motions if you want to win. And that’s what much of life is about – trying to beat the competition and win.

HQ: Is there a professional athlete you look up to?

CHELLGREN: Of course the Super Bowl is this weekend and a guy I’ve got to know casually is John Elway. He has a number of car dealerships that use Valvoline. I’m a great admirer of John. Brett Favre of the Packers is an extraordinary athlete. I don’t know him personally, but when he takes the field you just sense that he is a winner, he makes things happen. Joe Montana was extraordinary. Those are individuals that can lift themselves and their team to a new level by the force of their own ability. That’s admirable.

HQ: Just 30 days after you were named chairman, Ashland Inc. came under fire by Providence Capital which cited the company’s poor stock performance. Providence then nominated a new slate of directors. Looking back on that situation, what did you learn?

CHELLGREN: Well, there were a lot of things to learn. Point One: Providence, in a sense, is representative of the world we live in. Regarding the governance of public companies, shareholders are much more active, much less patient of underperformance, much more testing of individuals. They were certainly testing me as a new C.E.O. That was one of the reasons we were a target on their hit list. There were also some performance issues, some shareholders not pleased with our returns and there were some changes occurring in the industry that some people felt we were not responsive to. In terms of what we learned, it was quite clear that we had to have more of a sense of urgency in some of our activities. Point Two: I think it is clear that we need to be more proactive in a number of areas in terms of developing and implementing our strategy. Point Three: I think it is clear that we need to be more proactive in one-on-one communications with major institutional shareholders as well as some of our traditional audiences which would include buy-side analysts. But we also need to be talking to sell-side analysts and portfolio managers. Those were the three lessons we learned.

HQ: If Ashland’s stock yielded a 20 percent return annually for five years, but stockholders demanded 40 percent, would you be willing to layoff workers, downsize, merge, consolidate, etc. to make it happen?

CHELLGREN: Well, the first thing you have to understand is how fair and how good is your relative performance compared to your peers? Is 40 percent an unfair target? You must be able to honestly say that the returns you are giving are competitive. Then, you have a challenge to manage expectations and aspirations. So the first thing you do is understand the performance of your organization compared with relative peer groups, bench marks, industry averages and the like. We’re not a high tech company. We’re not Intel. But you are what you are. Now that begs the question of changing your portfolio mix and your strategy over time, and that’s a broader, longer-term issue. In the short run, you play the hand you’re dealt. However, I will be honest and say that if you perform that analysis and conclude that there is a chronic underperformance, then it is quite clear that either I, as a chief executive, or if I don’t do it some new chief executive [Smiles], must mak! e the hard decisions to bring the institution up to a competitive level. It’s a tough, hard world out there and if anyone thinks you operate in a vacuum, they don’t understand the reality of business these days. When John Hall became chief executive officer we had less than 10 percent of our stock owned by institutional investors. It’s now more than 65 percent and it’s growing every month. And these institutional investors have changed. They don’t have the patience they used to have five or 10 or 15 years ago. So, if you don’t understand the reality of that as the C.E.O. of a public company, you’re whistling in the dark.

HQ: Wall Street really controls the economy.

CHELLGREN: That’s who owns corporate America and that’s how it works. If people don’t believe that, then read the Wall Street Journal every day.

HQ: With the Marathon merger, the petroleum headquarters have been moved to Findlay, Ohio. With SuperAmerica’s headquarters in Lexington, Ashland Chemical’s headquarters in Columbus and A.P.A.C.’s headquarters in Atlanta, what’s keeping Ashland Inc. from moving its headquarters to one of those bigger cities?

CHELLGREN: This is a question that has been asked of this company for years. We have no current plans to move. There are a lot of benefits in being here. We have an enormous investment in people, physical facilities, systems and we’re not unhappy where we are. But, again there are no guarantees and one can never say never.

HQ: What does the Marathon merger mean to local employees. There have already been 300 workers laid off. How many layoffs are we looking at before it’s all over.

CHELLGREN: The numbers we’ve talked about are 125-150 job eliminations and 125-150 jobs to be transferred to Findlay, Ohio. And we’re starting off at a base of about 3,000 people here in the Tri-State. So, in a sense it’s about 10 percent of that. We are finding that some people whose jobs have been transferred are choosing not to go. There are a lot of individual reasons – they are near retirement, they have working spouses, they are not the primary wage earner and various other reasons. But at least an offer has been given. We’re also trying to create opportunities in other places within the Ashland family both in Lexington and Columbus, areas which are growing in employment. But, as of now, that’s what we see as the scope of the change. My impression is that the fear was that the job losses could be significantly greater than that and since we actually began to announce the numbers that some people were comforted. Although the reality is that people a! re now moving. On the street I live, a third of the houses have “for sale” signs. But having said that, this goes back to the “highs” and the “lows” issue we discussed earlier. In a sense, the C.E.O. is charged with keeping this enterprise competitive for the next 74 years. And this business was going through such change that we were either on the defense or the offense. We were looking at shrinking and a long, drawn out expense reduction scenario. And that was going to be slow and painful and I’m not sure at the end of the day if we would have had a competitive enterprise that could survive for decades to come. I’m convinced the Marathon/Ashland Petroleum joint venture is sound and that we will be competitive and this enterprise will flourish. So, the jobs that are left should be more secure. My wife is a gardener and says, ‘Sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind. You have to prune so what’s left will be healthier.’

HQ: The quarter ending December 31, 1997 saw Ashland post a 44 percent increase in earnings over the same period last year. What were some of the things the company did right?

CHELLGREN: Well, we did a lot of things right. It was a very solid quarter across the board. Almost all our lines of business did as well or better than last year. We were able to harvest the benefits of a number of improvements and growth. Ashland Chemical was making acquisitions, APAC was making acquisitions. SuperAmerica and Ashland Petroleum had the largest increase in profitability and that was driven by cost reduction. Crude oil, fortunately, dropped in price as the quarter progressed. It jumped up a lot in October when Sadaam Hussein stopped allowing the U.N. weapons inspectors there. Our corporate expense was lower because we sold our exploration company last summer. Our coal company began to capture some of the benefits of the merger. It was just a good, sound quarter.

HQ: So, we can assume that Providence Capital was happy with the quarter?

CHELLGREN: We haven’t heard much from Providence since the flurry of last fall and winter.

HQ: What is your strategic vision for Ashland in the 21st century?

CHELLGREN: It’s a high performance company that is generating top quartile total returns to its shareholders. It’s a company that is focused and in a relatively few lines of business. Right now, we’re three wholly-owned and two partially-owned companies all in related fields. We’re in industrial, marketing, transaction-intensive businesses with high market shares. Every one of these companies is number one or number two in their relevant markets. I think our business portfolio will be similar to what it is today, although broader. And I hope we will continue to be perceived as a good place to work, a fun place to work, and a responsible community citizen.