Huntington is revered as a quiet and secure community. But lurking in its past is a dark side with true stories of sensational crimes.

By Joseph Palatina

HQ 33 | AUTUMN 1998

When Mrs. J.E. (Ruby) Miller pulled into her driveway shortly before 11 a.m. on May 27, 1957, she didn’t expect to find someone burglarizing her fashionable home in Huntington’s southeast hills. Hearing suspicious noises coming from inside a bedroom, she armed herself with a shotgun and proceeded to investigate the source of the sounds, thus setting into motion a chain of events that would lead to her murder.

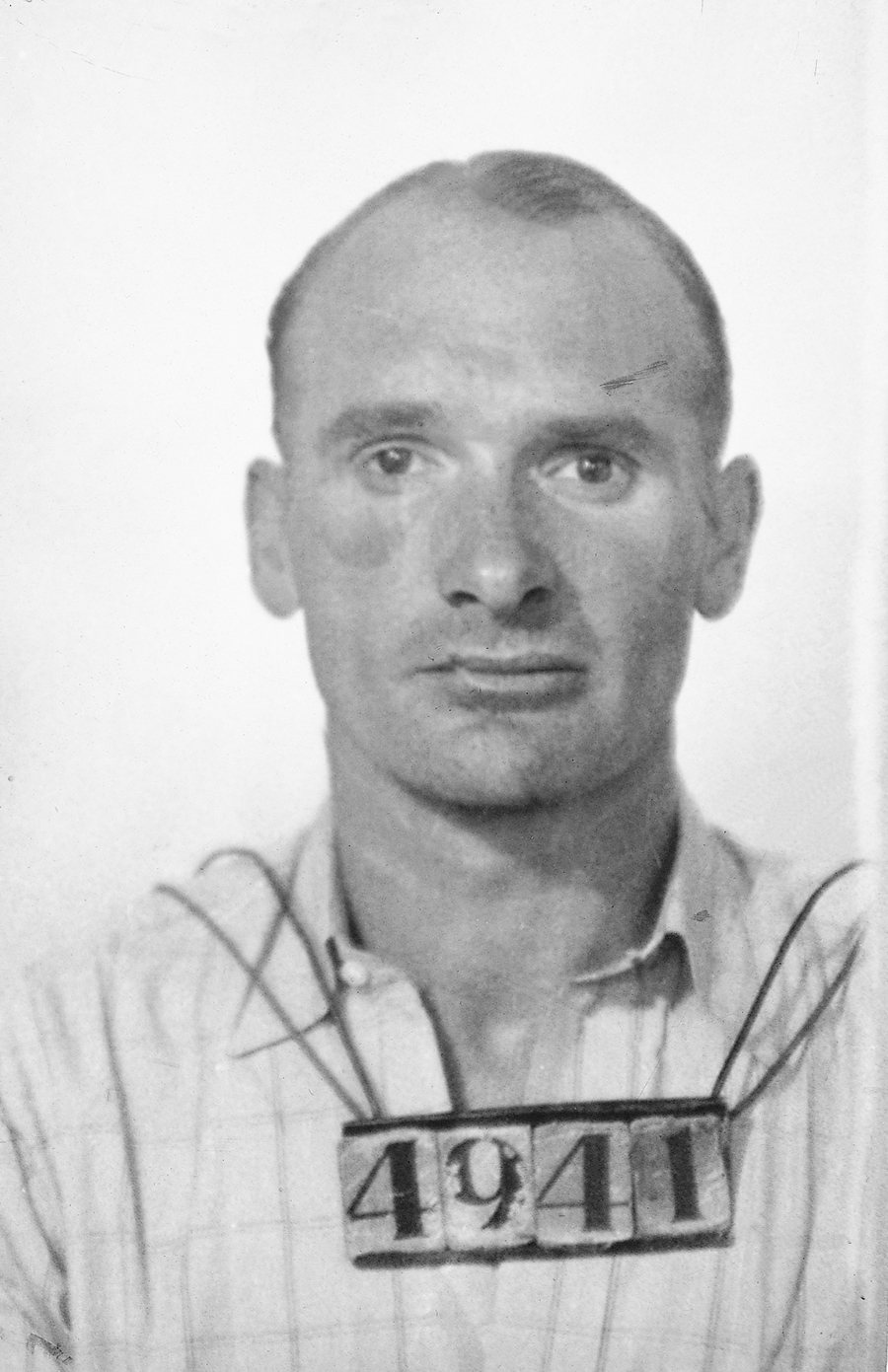

Front page headlines of May 28, 1957 state that a handyman and ex-convict named Elmer David Bruner had confessed to the May 27 bludgeoning-style murder of 58 year old Ruby Miller, wife of a prominent local contractor, who lived at 2021 Washington Boulevard. The article adds that Bruner, “a Huntington odd jobs man,” was a 39 year old convict who had been sentenced to prison three times previously.

Bruner admitted to breaking into the Miller home after cutting a screen in a window. He was ransacking a bedroom when he heard someone enter the house.Bruner told law enforcement officials that he opened the bedroom door and was confronted by Miller holding a shotgun. In his statement he said that “he wrestled the gun from her and ‘picked up something and began hitting her with it.'”

An article states that Miller was “brutally beaten with the claw end of a hammer.” It adds that her body, “the skull crushed by more than a dozen blows and blood splattered on the bed and wall, was found in a guest bedroom of her home. A blood-stained hammer lay nearby.”

Bruner’s confession came after more than four hours of questioning by police detectives. The ex-convict had been sought in connection with an armed robbery and two burglaries.

An article reports that at the time Bruner was apprehended following a telephone tip, police were unaware of the Miller murder. It adds that when he was arrested, he had the keys to a car stolen from the Miller home.

Brunerwas indicted for the murder of Ruby Miller and brought to trial the week of June 28, 1957. Bruner was one of six children of blind parents and had reached only the fifth grade in school.

After a trial before packed courtroom crowds, “an all-male jury” found Bruner, who consistently maintained his innocence despite confessing to the crime, guilty of murder in the first degree without a recommendation for mercy, making the death penalty mandatory, states an article. He was sentenced to the electric chair at the West Virginia Penitentiary on August 2, 1957. The West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals upheld his conviction. During the next several years, Bruner exhausted a series of appeals including an appeal for clemency from the governor. The final date for his execution was set for March 27, 1959. An article reports that “This was Good Friday so Gov. Underwood moved it to April 3, 1959.”

Bruner has the distinction of being the last person to be executed in West Virginia before the state abolished the death penalty in 1965.

Less than eight months after the murder of Mrs. Ruby Miller, Huntington was rocked by news of †† a particularly brutal crime of violence. On a bitterly cold Saturday night, January 4, 1958, Mrs. Inez Booth, age 51, was found riddled with stab wounds and near death in Rotary Park, a remote 95-acre park in Huntington’s southeast hills. She died shortly thereafter.

That night Mrs. Booth, wife of Melvin Booth, a grocer in the Guyandotte section of Huntington and a former city councilman, was forced from her Collis Avenue home at knife point and into a car. She was driven to Rotary Park where she was raped, slashed on the throat, abdomen and right leg and left for dead.

According to a news story, Mrs. Booth named her assailant to a police sergeant who found her at about 11:30 p.m., in shock and mutilated, lying on the ground behind a residence at 12 Glendale Avenue, on a hillside below Rotary Park.

Below an embankment police found a pool of blood where the victim had lain before she dragged herself to the Withrow home on Glendale Avenue. The police said it appeared the victim had been thrown over the steep embankment behind the Withrow home and left for dead.

Mrs. Booth again named her attacker in the presence of police officers, doctors and nurses just before she died in a Huntington hospital. Charged with the rape and murder of Inez Booth was Larry Paul Fudge, a 25 year old paroled convict who had been released just three weeks earlier from a federal prison after five years of a 15-year sentence for extortion.

Fudge, who was divorced and the father of a young child, was a former Huntington East High honor student. In 1952, he had been arrested for an extortion plot against a 17 year old girl and her family.

The Booths were, at the time of the extortion crime, neighbors of the Fudges and Mr. Booth “was a co-signer of the $25,000 bond which was required in the extortion case.” In fact, Larry Fudge had grown up with the Booth’s children and three weeks prior to the murder of Mrs. Booth, Fudge had visited the Booth home.

Fudge was described as a “model prisoner” during his stay at the Lewisburg, Pa. federal prison. Since his return to Huntington, he had been employed at a television sales and repair shop and had been given permission to buy a car.

Police in their reconstruction of the crime showed that Mrs. Booth had been abducted at her home in mid-evening while she was reading. Mr. Booth told officers that he “returned home from his store about 10:30 p.m. and found his wife’s reading glasses and an open book on a table in the house,” states an article.

Before she died, Mrs. Booth told authorities that she was forced to leave her home at knife point after she answered a knock at the door. She was then forced into a car and was driven to “a wooded place” where the assault and knifing took place.

The crime scene was remote from any homes in the area, explains an article, adding that the temperature was seven degrees that night and it would have been unlikely that anyone would have heard an outside disturbance. Part of the attack occurred inside Fudge’s car.

Less than an hour after Mrs. Booth was found, Larry Fudge was in custody, arrested at his parents’ home in the Altizer section of Huntington. Police took a blood-stained “two-bladed knife from Fudge at the time of his arrest,” according to the article.

It adds that on a vacant lot near Fudge’s home, a police search discovered a woman’s garter belt and a stocking believed to be the victim’s.

Justice was swift and certain for Larry Fudge. According to Cabell County Circuit Court records, in February 1958, an indictment of first degree murder was returned by the grand jury against Larry Fudge. This was due primarily to the “deathbed statement” given by Mrs. Booth. Fudge pled guilty to murder in the first degree “without any recommendation (for mercy) by the Prosecuting Attorney’s office.” His conviction date was March 12, 1958 and on March 28, he was sentenced by Judge Daniel of the Common Pleas Court to “death by means of the electric chair on July 1, 1958.” The sentence was to be carried out at the West Virginia Penitentiary at Moundsville.

As the execution date drew near, an Associated Press story published in the Huntington newspaper states: “As he (Fudge) left death row for a new cell in the shadow of the chair, the personable 26 year old slayer said goodbye to another condemned man from Huntington, Elmer Dave Bruner. Fudge ordered steak again for his noon meal.

“A prison quartet out in the yard began to sing religious songs. They were age-old songs to comfort, but no one knows whether Fudge could hear them from his windowless cell,” says the story.

The AP article states that Fudge “was transferred from death row to an almost hygienically clean room near the death house at 9 a.m. yesterday, just 12 hours before his date with the electric chair.”

Court records report that on Tuesday, July 1, 1958, “at 9 p.m. Eastern Standard Time,” Fudge was electrocuted and pronounced dead.

Larry Fudge was the first Cabell County resident to die in the electric chair since that form of capital punishment was made legal by the Legislature in 1949.

As daybreak approached, a long, hot summer night shift spent waiting on customers was nearing an end for Bernie Estep, night counterman at the Hub Cafe, located in the 1000 block of Fourth Avenue. Then suddenly, the quiet of the pre-dawn hours was shattered by gunshots and a woman’s scream coming from an apartment across the street over the Palace Theater. Estep called the police. It was Tuesday morning, July 28, 1959.

Tenants of the apartment building told police officers that they had heard shots, but were unable to determine where they originated.

When police returned to the sidewalk, they saw Mrs. Dora Keck Schweitzer standing on the fire escape outside her apartment. She told officers that the shots came from “up the street.” An hour and 20 minutes later, police again saw Mrs. Schweitzer, this time in front of the Palace Theater. She told them: “My husband has been murdered.”

The distraught woman said that two men had forced their way into the apartment, robbed her husband of $3,000 and a diamond ring, and then killed him. She stated that one of the men was inside holding a gun on her.

Shortly before 6 a.m., police found the body of 73 year old William Schweitzer in a pool of blood in the tiny apartment. He was kneeling beside the bed in the bedroom/living room. A small hand ax was found by his right hand and an open knife was under his left hand.

The front page newspaper account reports that numerous lacerations were found on Schweitzer’s head and that his body was so mutilated that it was impossible to determine how many times he had been shot. One bullet was found lodged in the wall and another was under the bed, states the article, adding that the slugs came from a five-shot .32 caliber pistol.

In the article, Dora Schweitzer was described as “a former hotel maid” who admitted shooting and hacking her elderly husband to death just 22 days after their wedding because she claimed he tried to kill her during an argument in their efficiency apartment at 1040 1/2 Fourth Avenue.

Mrs. Schweitzer, 50, said she killed her husband because he had attacked her with a knife. It was reported that Mrs. Schweitzer had “numerous cuts on her arms.” The argument arose after Schweitzer accused her of dating another man.

A Huntington pathologist told the newspaper that Schweitzer’s death was caused by a bullet from a .32 caliber pistol that entered his back and severed the spine. A second bullet struck him near the right eye. The victim had also been brutally attacked with an ax, causing a fractured skull.

The couple were married on July 6, 1959 at Harts in Dora Schweitzer’s native Lincoln County. William Schweitzer, who was a native of Germany, was a retired railroad machinist who moved to Huntington from Wisconsin and drew a pension.

At the time of the murder, Dora Schweitzer was out on bond on a larceny charge in connection with the theft of $500 from a local man, states a news story.

After questioning by police, Mrs. Schweitzer stated that she couldn’t remember using the ax in the commission of the murder of her husband and said that she must have “blacked out.” The accused woman waived a preliminary hearing before a magistrate. She was then ordered held without bond for grand jury action and committed to the county jail.

An article says that “her new husband (Schweitzer) posted bond for her release on the larceny charge.”

Records at the Cabell County Circuit Clerk’s office show that Dora Keck Schweitzer pled guilty to second degree murder and was sentenced from five to 18 years at the West Virginia Prison for Women at Pence Springs.

On April 29, 1965, Mrs. Dorothy S. Christian, a 32 year old United Fuel Gas Co. telephone operator, was found murdered. Her lifeless body was discovered lying on the rear seat of her locked automobile that was parked in an alley near Marshall University.

A newspaper article states that Mrs. Christian “was killed by someone who wrapped a bow on the victim’s blouse around her neck and strangled her by exerting ‘a powerful force’ in applying a garrote.” The article of clothing used in the crime was found 30 feet from the victim’s car. Her “clothing was found in disarray,” says the article.

Mrs. Christian, who was married and the mother of one child, had been employed by the gas company for 12 years. Her husband also worked for the utility.

A report states that “it was believed the woman was approached by her assailant at 12th Street and 6th Avenue, where she generally parked her car. He then apparently forced his way into her vehicle and ordered her to drive to the nearest secluded spot…it was dark at the time.”

Mrs. Christian was last seen at 6:20 a.m. in the 1100 block of 6th Avenue. Then minutes later, her car was spotted in the 1500 block of 5 1/2 alley, more than three blocks from where she normally parked when she went to work.

Specifically, Mrs. Christian’s car was “parked near a double garage at 542 15th Street,” states a news story, adding that fingerprints were found on the car.

After an intensive police investigation failed to turn up any leads, the Huntington Publishing Co., then the publisher of The Herald-Dispatch and the Advertiser, offered a $2,500 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Dorothy Christian’s killer.

An article reports that the publishing company received “a near deluge of calls following the announcement of the reward,” and tips were received and checked out by the police.

On July 23, 1965, the reward was increased to $3,000 and an article reports that “the murder probe was at a standstill.”

An article published the following year reports that there were no substantive leads in the case. More than 30 years later, the strangulation murder of Mrs. Dorothy S. Christian remains an unsolved crime.

Editor’s Note: The Huntington Quarterly had intended to publish the story of the mysterious death of Huntington Patrolman Clemmie Curtis in this issue. However, out of respect for his family and their request for privacy, we have decided to cancel the article.