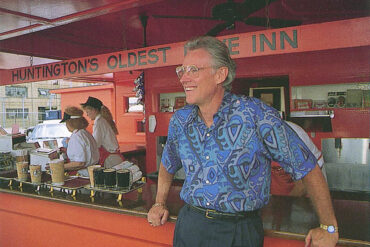

Philanthropist Joan Edwards has found a home in Huntington and is transforming the region with her generosity.

By Jack Houvouras

HQ 39 | SUMMER 2000

She isn’t what most people expect. She isn’t frail or tired or stuck in a rocking chair. Instead, she is vibrant, outspoken and attractive. Her age? It doesn’t matter. She says she still feels like she’s 21 years old most days and she has the energy to prove it.

At any given function, you will find her immersed in a blitzkrieg of conversation. At a recent charity reception, for example, she stood in the middle of a crowded room surrounded by cameras and hot lights. She held reporters, politicians and business leaders entranced with a story about one of George Washington’s relatives who once owned Audley – the Edwards’ horse farm in northern Virginia. She’s hard to miss with her striking white hair and easy smile. Onlookers just watch and listen as she reels off story after story. Charming, dynamic and graceful, her enthusiasm elevates the spirit of nearly everyone in the room.

Most people in the Huntington community know Joan C. Edwards from her philanthropic work. She first came into the spotlight when her husband of 54 years, James F. Edwards, passed away in 1991. In accordance with his will, Joan graciously handed out generous contributions to the community totaling nearly $20 million. Over the last decade, she has continued to give back to the Huntington area with her own money. The gifts Joan and Jimmy have left now total over $40 million. But why? Why has Huntington been the recipient of such unprecedented generosity? Why does Joan Edwards, a woman from New Orleans who only lived in Huntington with her husband for a few short years, care so much about this region? To answer that question, you must first understand her life.

She was born in London, England, and at the age of four moved with her family to New Orleans, La. From an early age, she could be heard singing around the house. By the time she was 11 years old, she had already caught the ear of a local manager at WWL Radio who asked her to sing on one of his shows. By the time she was 13, the radio station had moved to the Roosevelt Hotel and Edwards, now a veteran performer, was singing with a full orchestra. At 17, the fiery, independent Edwards locked horns with her mother regarding her future.

“Mother really wanted me to go to college,” said Edwards with a charming New Orleans drawl. “But, I wanted to join a girls’ orchestra that was going on tour. ‘Joan, I don’t know if I can allow that,’ she told me.”

Fortunately for Edwards, a friend of the family was serving as a chaperone for the group and, as was usually the case, Joan got her way. She then set out to see the country. She was with the group for a short time before leaving to sing the “sugar Blues” with Clyde McCoy and his Kentucky band. While with McCoy, she also made a few movie shorts. From there it was off to Chicago, New York and several other cities along the way. By the time she was 18, she had already seen most of the country.

“I was never homesick,” said Edwards. “And I wasn’t smart enough to be scared. But you know, times were different then. I had 12 big brothers from the orchestra looking out for me. I would go into a bar and ask for a glass of milk. And, if someone had made a pass at me, I would never have known it.”

Eventually, fate found her in Pittsburgh singing at the William Penn Hotel. In the crowd one evening was a young man from Huntington, W.Va., who was working at a division of his father’s company – the National Mattress Company (Namaco). He asked to meet the singer backstage. His name was Jimmy Edwards.

“After we met, he became a frequent visitor of the hotel. I would look out into the audience at lunch, and he was there. At dinner, he was there. Needless to say, we started dating.”

Seven months later, Jimmy Edwards asked Joan to marry him. She responded by saying they should probably wait several months.

“Why?” he demanded. “let’s just do it.”

But Joan insisted. “I can’t marry you until you meet my mother and father and I meet your parents,” she countered. “that’s just the way I was raised.”

The two were married at a small ceremony in Pittsburgh. Joan inherited three children from her husband’s first marriage. They lived in Pittsburgh for a short time before Jimmy’s imposing father summoned the newlyweds to return to Huntington.

The family moved into their new home at the bottom of Fifth Street Hill while Jimmy and his father were absorbed in work at the mattress company.

“That was a very difficult time,” Joan recalled. “Jimmy and his father were so much alike. They were always arguing and I was always stuck in the middle, trying to smooth things out. But they were also very close. Everything was “my dad, my dad” and “my son, my son.” I mean, they were close.”

After returning to Huntington, Jimmy cleared off some land above their home and built a barn. He then had horses shipped down from Pittsburgh and hired a groom from England to oversee his makeshift farm.

“He had always loved horses,” Joan recalled. “In Pittsburgh, the children had ponies and showed.”

What began as a hobby for the businessman escalated over the years into a small obsession. Every Sunday, Joan could find her husband sifting through newspapers looking for the latest news on horseracing. “Finally one day I said to him, “Jimmy, you’ve provided us with a wonderful home. The children have all they want. I have all I want. If you want a racehorse, please go buy one. I think you deserve it.”

Edwards took his wife’s advice and purchased his first racehorse. But, as Joan would soon learn, the animals multiplied like rabbits. What began as a couple of racehorses culminated with Edwards buying a racetrack. He began by purchasing Fairmont Park in southern Illinois. Using his business savvy and his wife’s flair for decorating, he turned the downtrodden track around. Next, he purchased Waterford Park in Chester, W.Va. One success led to another, and he then bought Scarborough in Portland, Maine. He eventually sold the tracks to the Ogden Corporation and obtained Suffolk Downs in Boston, where he finished his racetrack career.

In his hey day, Jimmy Edwards had more than 250 racehorses at his beloved Berryville, Va. farm. At one point, he owned four highly-profitable racetracks. This success, coupled with the success of the National Mattress Company, provided him with a large fortune. But, as Joan likes to say, “money is only good for two things – spending on women and betting on horses.”

The couple, under the guidance of trainer John Dunlop, who also trained horses for the Duke of Norfolk, raced horses throughout the United States, Canada, England and Ireland. They also kept the leading stable at Nice, in the south of France. Their horses won many large races including one at the prestigious Royal Ascot meet in England.

In the United States, they were pioneers in the training of horses. Their sandpath at Audley, used for training horses to run in muddy conditions, was copied by the Duke of Norfolk. They also were among the first to provide their horses with a therapeutic swimming pool and sauna.

The Edwards’ colorful career in the racetrack business found them running with the likes of captains of industry, British royalty and presidential hopefuls. The horseracing game was often glamorous, always exciting, and it introduced Joan to the world of business. Her husband, who went away to school and summer camps during most his childhood, didn’t like to be alone and would often have his wife sit in on meetings.

“He never asked me if I’d like to go somewhere, he’d just say we’re going.”

In the years that saw the couple revamp several major racetracks, Joan became an integral part of their success. She learned to work with contractors, oversee work crews and stand toe-to-toe with men.

“Jimmy had an expression: “Never stand still.” He was a tireless worker. I think one of his greatest strengths is that he could charm a snake and be just as tough. He was my friend, my husband and my companion.”

In 1991, Jimmy Edwards passed away. He was 81. Shortly after his death, his wife of 54 years called a press conference and announced that as part of his will, she was presenting $1million to the Marshall University School of Medicine; $1 million to the Huntington Museum of Art; $2 million to the Episcopal Church; $16 million to Cabell Huntington Hospital for construction of an adult cancer center and other significant contributions to organizations including the Cammack Children’s Center and the Stella Fuller Settlement.

Nearly a year after those presentations were made, Marshall University announced that Joan Edwards had decided to donate another $1 million, this time to the Fine and Performing Arts Center. And, a year later, the university announced that Joan wanted to do more for the university and had pledged $2 million to assist the school’s most pressing needs. University officials elected to apply the gift to the athletic department. The school then named the Marshall University Stadium field after the late James F. Edwards.

Since his death in 1991, Joan has continued her husband’s efforts. Most recently, Mrs. Edwards announced that she will leave a bequest of $16 million to the Marshall University School of Medicine for the building and support of a children’s cancer center. Additionally, Edwards will give $2 million for preliminary planning, development and design. The facility, to be named Children’s Pavilion for the treatment of cancer, will be built in front of and contiguous with Cabell Huntington Hospital on the hospital’s health science campus.

To honor Edwards’ generosity, Marshall President Dan Angel announced that the medical school henceforth will be named the Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine at Marshall University. Approximately one third of the 123 medical schools in the country are named after benefactors or distinguished alumni. Of those, Marshall’s will be the only one named after a woman. The news came as a surprise to Edwards.

“I am flattered,” she said after the announcement. “I am overwhelmed that they would do this. I have goosebumps. I wish that I could do more. It has been a joy to give back to this community.”

Angel thanked Edwards for the work she has done for the university and for students. “Joan has contributed to every aspect of the university and proved that she is a supporter of higher education. She cares about students and her contributions will ensure that students will have the opportunity to be successful in the future.”

Joan explains why she plans to donate so much to cancer treatment. “I”ve lost a husband, a sister and a son to cancer. I want to help the children who now must go elsewhere for treatment. In some small way if we know that we’ve left something that will save life or pain for people, it would be wonderful.”

In the Children’s Pavilion, Edwards would like there to be a play area filled with toys and named for her son, Charlie, who died of throat cancer while in his forties. She would also like to see a small walled-in garden where the children receiving treatment can plant their own flowers. She playfully requests that there be a Mynah bird in the garden that learns the children’s names.

Much of Joan’s generosity following her husband’s death has been fueled by her commitment to the region.

“When I first moved to Huntington, it was a nice river town. But over the years, I have seen stores close, I have seen young people leave,” she says softly. “It’s very distressing to me. I hate to see the young people leaving. That’s the reason I was so interested in giving money to Marshall.”

The Edwards’ generosity to Huntington has been delphic in its foresight. By giving to the arts, athletics, academics and health care, the Edwards family has forever impacted each facet of life in Huntington.

Dr. Charles McKown, dean of the School of Medicine and close friend of Edwards, recognizes the importance of her work.

“The Edwards family may have done more for Huntington than the Mellons did for Pittsburgh or the DuPonts did for Wilmington, Delaware. What Joan has done is support the infrastructure of this community that will make the quality of life better for years to come. Huntington does claim her, and God knows they should.”

Marshall is the only school that receives contributions from Edwards. “When I decide to do something, I do it. I like things to move. I’ll say one thing about Marshall University – when you tell them what you want, it’s almost done before you finish your sentence.”

Today, Edwards travels extensively. She recently returned from a tour of southeast Asia that included stops in Cambodia, Vietnam, Bangkok and Burma. But despite her wealth, Edwards remains self-effacing and doesn’t forget her humble beginnings.

“My father was a CPA,” she says. “We never had anything like this. I am still overwhelmed.”

In her spare time, Edwards enjoys gardening and cooking, and golfs twice a week. She says she likes to golf late in the afternoon because that’s when the men are gone.

“They’re stalling on the green, gambling and writing down scores. I push them along,” she says sternly.

“I’m glad I’m here,” she quips, “life is green. I hope to live a little longer and drink from the fountain of youth. I hope I’ve done some good things.”

It was in Huntington that Edwards found the roots and the home she didn’t have as a child. “You might say I was an orphan,” she says. “My formal schooling was in New Orleans, but my roots weren’t second or third generation deep. Jimmy had family here and he wanted to leave something behind. I want to continue what he started.”