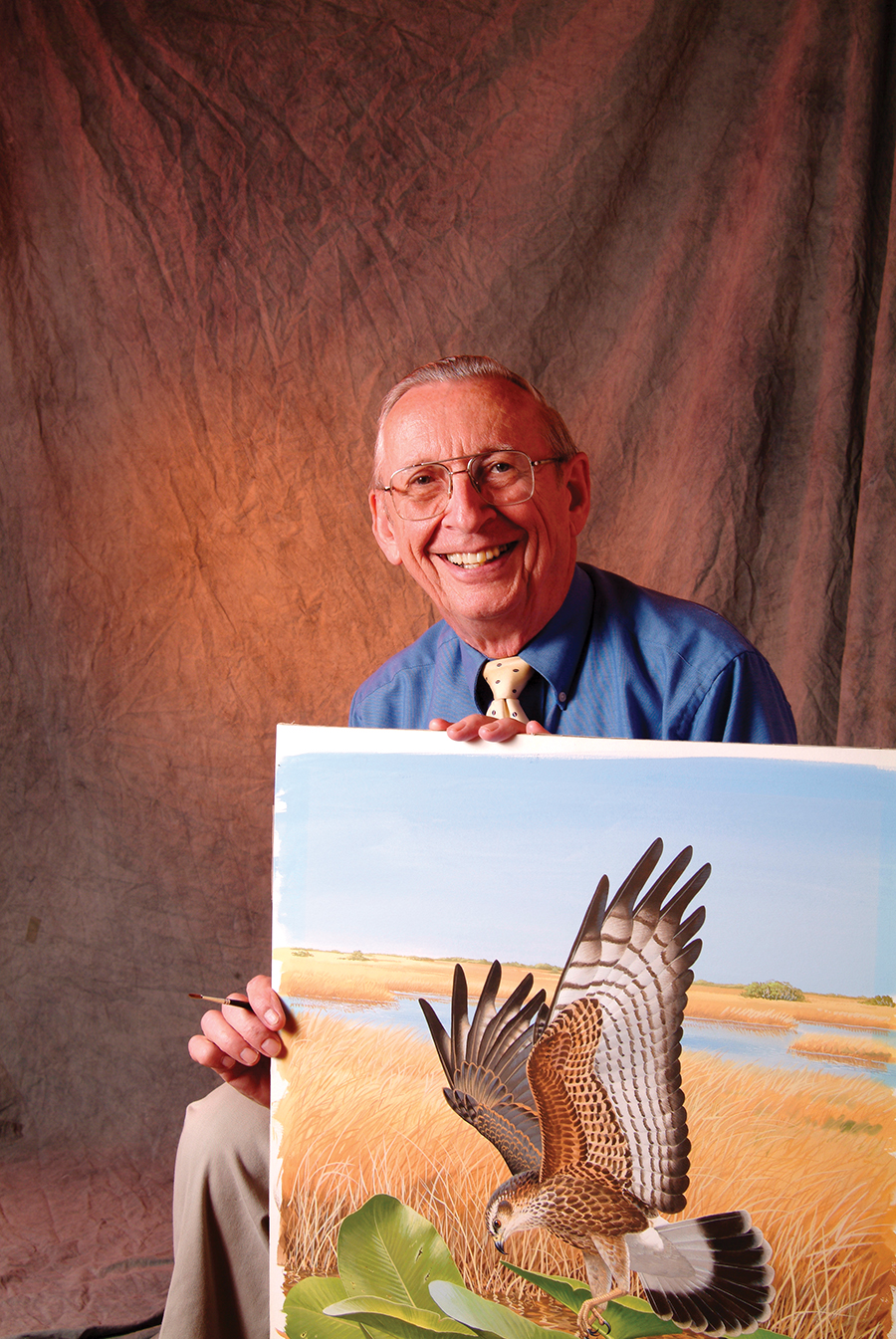

Meet Huntington resident Chuck Ripper who is renowned throughout the country for his work as a gifted wildlife artist

By Susan Hahn

HQ 48 | SUMMER 2003

Lucky is the person who knows what they want to do in life, and has the talent to create the opportunities to achieve that goal. Huntington resident Chuck Ripper, acclaimed as one of the leading nature and wildlife artists in the country, is one of those people and he has done so without much local fanfare.

Although his prolific body of work includes illustrations or paintings for books, magazines, catalogs, museums, stamps, universities and even candy bars, Ripper seldom is recognized in town unless he is attending an art show or some other event for artists.

“People come up to me and say, ‘I know you paint birds but what do you do for a living?’” Ripper says laughing. He tells them he makes his living as a commercial artist. “Most people don’t realize that I do this stuff because somebody commissions it and it’s going to be reproduced and that makes it commercial,” Ripper explains. “The client decides the subject, what season, the proportions and the deadline. For example, the United States Postal Service has a policy if you do artwork for postage stamps, the art can’t be more than five times the size of the stamp. They found over the years if you make the painting too large and then reduce it down to postage size, it melts together like yesterday’s spaghetti.”

In many instances, Ripper retains ownership of the original artwork and many of his paintings have appeared in more than one publication. Recently Ripper received in the mail the 2003 L.L. Bean spring hunting catalog with one of his paintings of a Beagle lying on a porch with a rabbit sneaking out from under the porch. It is a whimsical scene that was so popular in 1967 when it first graced the cover of a L.L. Bean catalog that the company ended up reprinting the cover to send to people who requested a copy. During that period Ripper painted a total of seven covers for L.L. Bean.

“They had obviously resurrected the cover but they had only bought onetime reproduction rights back then,” Ripper says recalling the conversation he had with a company representative. “He said, ‘Golly, everybody you worked with is either dead or retired. We didn’t know.’ I wasn’t mad at them and they settled up nicely.”

The painting was originally produced for Pennsylvania Game News and also graced the cover of Fur-Fish-Game magazine after the first L.L. Bean cover.

Ripper painted another rabbit, also one of his favorite paintings, for Audubon magazine. After the painting appeared in the magazine, he sold it to a manufacturing company headquartered in Pittsburgh for their new expanded facilities in Ashland, Kentucky. During the late 1980s another company purchased the company and the painting was given to a retiring executive.

While Ripper knows where the Audubon painting is, there are many paintings he has sold that he has lost track of. “Sometimes these things just disappear into a closet or a yard sale and you never know where they go,” Ripper says.

No matter what the composition of the original artwork is, most commissions lead to other jobs. Ripper tells the story of how he came to work on one of Roger Tory Peterson’s field guides. Peterson was a noted artist specializing in birds, and he created the first field guide and became the respected editor of a series of popular field guides.

“I did a lot of work for the National Wildlife Federation including 575 conservation stamps. Peterson was the art director for the stamp program so he was familiar with my work. He asked me if I would do the illustrations for a book he was planning and I said, ‘Look, I’m a bird man and I know dang well you aren’t going to ask me to do a bird book because that is what you do.’ He wanted me to do a book on wildflowers. I said I’m not a botanist. He said, ‘Botanists are forever counting the hairs on things and would never get it done. You’re a commercial artist and the book is for the laymen and you can look at it from the layman’s standpoint.’ He was very persuasive. Since the book is half art and half text, I actually am a co-author.”

Ripper produced 1,492 illustrations of flowers for the “Field Guide to Pacific States Wildflowers,” part of the Peterson’s Field Guide Series. Ripper notes, “as the old country musician sings, ‘I’ve paid my dues.’”

Ripper is known for his attention to detail and the research he does for each assignment. Once when he received a commission to do a painting of a rare orchid, his search for information about the orchid was coming up short. Finally he got ahold of someone who directed him to someone in Huntington who was an expert on orchids. Some would call that luck, others would call it perseverance, a trait that Ripper has in abundance.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania the day before the stock market crashed in 1929, art was in Ripper’s genes and he was bent on being an artist from an early age. His mother taught art in elementary school. His father worked as a blacksmith making ornamental ironwork for carriages and painted landscapes in his spare time.

Ripper points out that his father didn’t lose any money in the stock market crash because he didn’t have any, a familiar refrain from that generation. During the Depression his father couldn’t find full-time employment so he turned to painting landscapes to make ends meet.

“It kept him sane,” Ripper says. “He sold his oil paintings for $2.50 up to $10.00. People still wanted a little something for the wife or for some occasion.”

Growing up in the little town of Evans City, about 20 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, Ripper spent most of his free time out in the woods and he still is an avid fisherman and outdoorsman. The young Ripper would tag along when his father ventured out in the surrounding areas to paint, and he learned a couple of lessons that have stayed with him throughout his life. He developed a lifelong interest in and respect for the majesty of nature, and that respect has earned him accolades for his conservatism. Since painting became a way to make ends meet during the Depression, there was an element of expediency to his father’s work. “He didn’t noodle around on his paintings,” he says. “You can spend half your life on one painting and you don’t learn anything, but if you do 25 paintings you are going to get better. I was a witness to that.”

While his father’s preferred medium was oil, Ripper doesn’t particularly care for oil. “I’m somewhat impatient at times,” he says. “Oil takes a while to dry and being a commercial artist up against deadlines, wet oil paintings are a disaster waiting to happen. Opaque watercolors are what rang my bell and that’s what I stayed with.”

Ripper uses oil every once in a while if he doesn’t have a deadline, and he occasionally uses acrylics.

By the time he was in high school, Ripper focused in on both his interests: art and nature and wildlife. He began taking classes at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh on Saturdays, continuing all through his high school years.

After graduation Ripper enrolled in the institute’s two-year commercial art program. Some of his relatives thought he should consider a four-year program, but Ripper wanted to focus on art and not be bothered taking subjects that didn’t really interest him. “At the Art Institute it was seven hours a day, five days a week,” he says. “I rode the B&O train back and forth everyday and brown-bagged my lunch. Otherwise it wouldn’t have happened.”

Before Ripper graduated from the Art Institute, one of his drawings was published in Nature Magazine, which led to his first commission. During his last week of school at the end of May 1949, he received a letter from William Morrow in New York saying they had a manuscript for a children’s book and asked him to send some samples of his work. Addison Webb, the author of the children’s book “Song of the Seasons,” had seen his drawing in Nature Magazine.

“I got on the bus and went to New York and ended up getting the commission to do the book,” Ripper says. “Since I had just graduated, I jumped right in and did the 61 drawings for the book from June to October.” He had illustrated his first book before his 20th birthday.

When he completed his first commission, Ripper returned to Pittsburgh and started looking for a job. “I figured if I was going to make a living at this art thing, it was going to have to be advertising art because nobody was doing wildlife full-time then,” Ripper says. “I figured I’d paint the critters on the side and do commercial art during the day. But then the first book I did was a nature book which kind of threw me a curve.”

One day he stopped by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, one of his favorite places, and started talking to one of the staff artists who knew his father from the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh association. One thing led to another and he was offered a commission to do a pen and ink drawing for the museum’s annual report.

“The drawing was of a skull of the famous tyrannosaurus rex,” Ripper says. After he submitted the drawing, he was offered a job as a staff illustrator at the museum.

“Things were going gangbusters at the museum,” Ripper says. “Then the Korean War got going full swing and the day after my 21st birthday, I got a notice to report for a physical,” Ripper says. When he was called up, he ended up using his expertise in drawing, working as a topographic draftsman for the Army’s Corps of Engineers.

During his stint in the army, Ripper was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood about 120 miles southwest of St. Louis, Missouri. He met his future wife, Virginia Ogle, at the USO club where she was serving as a hostess.

“We got to playing Ping-Pong and she whipped me something awful, and I thought I was pretty good,” Ripper says. “She was also an artist. And, her father was a sportsman, hunter and fisherman so things kind of clicked.”

After he was discharged from the military in 1953, he couldn’t find a job in Pittsburgh so he took a job as the art director with Standard Printing in Huntington. He and Virginia married that August and moved into a little apartment that he categorized as not much bigger than his current home studio.

In 1959 they moved into their present house in West Huntington and his studio is filled wall-to-wall with art that he has created throughout the years.

There is one painting of a fly fisherman casting for trout on the Cheat River in Shaver Fork that could be a self-portrait of the artist. He lets viewers draw their own conclusion. The gallery actually spills into the entire house with artwork created by various family artists in just about every nook and cranny. The bookshelves in his studio are full of a myriad of magazines and books, some of which he wrote and illustrated, and others that are for reference. “We planned on staying in Huntington for two or three years,” Ripper chuckles. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary this year.

After moving to Huntington, he wrote and illustrated a book about every year and a half in addition to working at the printing company. “That was the beginning of my moonlighting.” Ripper illustrated and wrote 11 children’s book on wildlife including bats, hawks, the weasel family, ground birds, trout, woodchucks and their kin, and diving birds.

“The book business opened a lot of doors,” Ripper notes. Other commissions were coming his way. While Ripper had learned a lot working at Standard Printing, he left in June of 1965 because the business was going bankrupt. “I thought this wildlife business was already the tail wagging the dog at that time,” Ripper says. “I was already doing stuff for the National Wildlife Federation and the children’s books and I thought if I am going to do this, now is the time.” He made some inquiries of clients to determine if staying in Huntington would hurt his chances of getting assignments. He was told that it didn’t matter and he chose Huntington as his adopted home. By then he and Virginia had three daughters, Elisabeth and twins Janet and Joy. Eventually all three graduated from Marshall University with degrees in art.

“There was a stage when I did a lot of freelance work,” Ripper says. “You just let me bid against a guy in New York and I’ll eat him up because his overhead is killing him.”

The commissions kept coming. Ripper’s paintings have been used on more than 100 magazine covers including L.L. Bean, Fur-Fish-Game, Virginia Wildlife, Southern Outdoors, North Carolina Wildlife, Pennsylvania Game News and Oklahoma Outdoors. His paintings have been shown in 15 museums and galleries. Ripper illustrated 25 books for publishers including the National Audubon Society, National Geographic Society, Readers Digest Books, Houghton Mifflin, Alfred Knopf, Museum of Natural History (Denver) and William Morrow.

In 1977 Ripper submitted a painting of a wild turkey named “Winter Morning” to the National Wild Turkey Federation stamp competition and he won first place. The organization issued a limited edition print and stamp of the painting. He completed eight plates of birds for a National Geographic book on “North American Birds.” Ripper also completed 53 of the 400 paintings in a book on “North American Birds” published by Reader’s Digest.

In 1980 and 1981, a series of Ripper designed stamps titled Corral Reefs and Wildlife Habitats were issued to popular acclaim for the United States Postal Service (USPS). In 1987 Ripper produced 50 stamps for the USPS depicting North American Wildlife. In another set, Ripper designed five stamps with different hummingbirds hovering over flowers that were issued in 1992. He has designed 80 stamps in all for the USPS.

In 1980 and 1981, a series of Ripper designed stamps titled Corral Reefs and Wildlife Habitats were issued to popular acclaim for the United States Postal Service (USPS). In 1987 Ripper produced 50 stamps for the USPS depicting North American Wildlife. In another set, Ripper designed five stamps with different hummingbirds hovering over flowers that were issued in 1992. He has designed 80 stamps in all for the USPS.

In 2001, a private company that issues stamps primarily for collectors produced a set of four Ripper stamps depicting life in the corral reefs for the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

Locally Ripper has had two one-man shows at the Huntington Museum of Art, he participates in area art shows and has done paintings for Spring Valley High School and Vinson High School. He painted a Bobcat for the Ironton campus of Ohio University and he was commissioned to do a painting of a herd of buffalo for Marshall in the 1970s. Ripper was the first alumnus to be honored by the Art Institute of Pittsburgh. He is included on the “Wall of Fame” at the Big Sandy Super Store Arena and he won the Silver Medal Award for Conservation Work by the National Association of Garden Clubs. He received an award from the West Virginia Library Association for writing and illustrating children’s books.

“There are a lot of things you can’t plan for,” Ripper says reflecting on his career. “Ninety percent of the time, the jobs I go after I don’t get, and then things just fall out of the woodwork.”

More recently Ripper was asked to do a four-page spread for National Wildlife magazine on butterflies, caterpillars and a host plant.

After it was published in the magazine, Ripper got a call from someone at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History explaining that they were building a butterfly garden where they have caterpillars, host plants and butterflies flying around.

“They had me do a series of 18 illustrations that were made into signs as a result of seeing the spread in National Wildlife magazine,” he recalls.

As a result of the signs in the museum, the catalog mail order company Earth Sun Moon has commissioned several butterfly designs as well as birds and flowers in a patriotic red, white and blue flag design for its T-shirts and sweatshirts.

“So everything interlocks as you see – that’s the way it goes,” Ripper says.

He plans to continue to work as long as he is physically able, quoting Hugh Downs saying: “‘I’m retired but not quitting. I can be more selective as to what I want to do.’ If it is something I want to do, I will do it.”