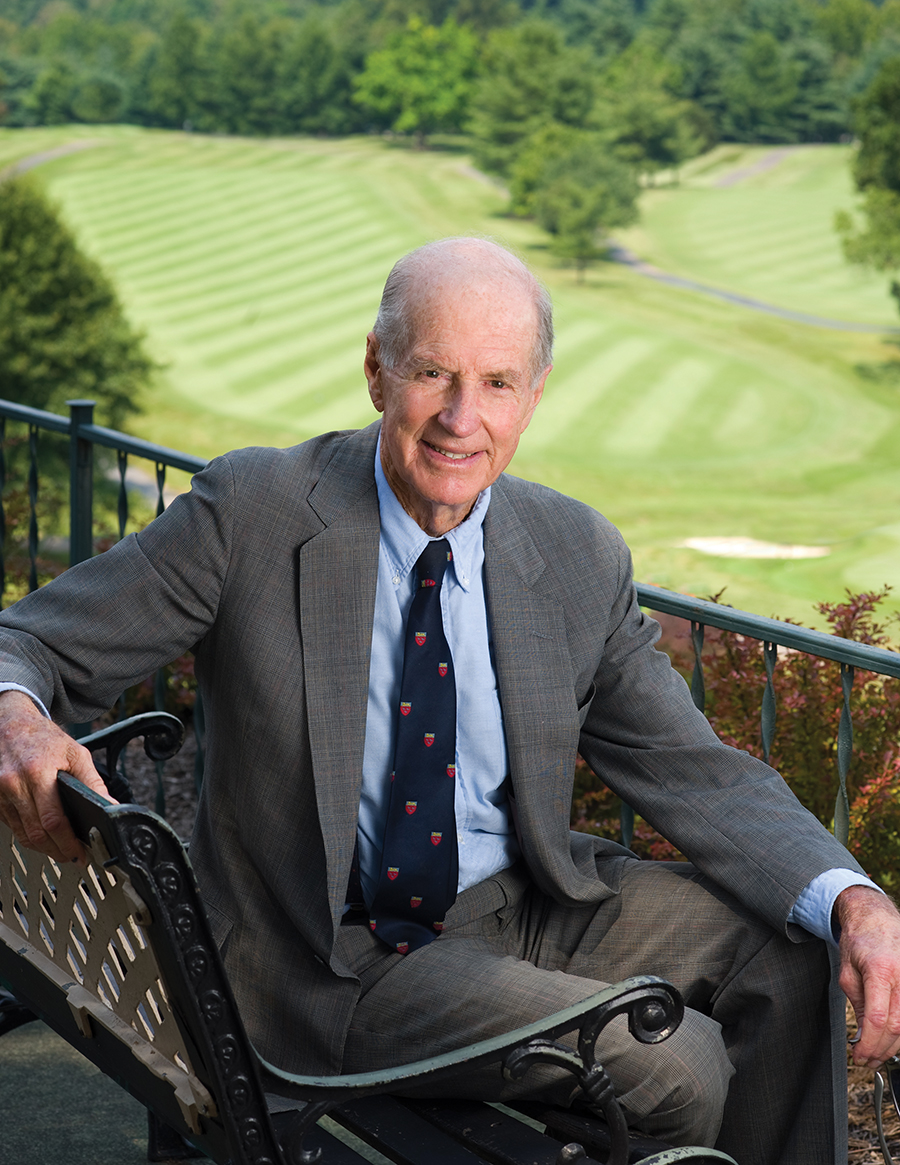

The life of golf’s last great amateur has been defined by achievements both on and off the course.

By Jack Houvouras

HQ 70 | SUMMER 2010

September 16, 1964. It’s nearly 8 p.m. and the sun is slowly descending behind the trees that surround the practice range at Guyan Golf & Country Club. Nearly everyone has left the course, but one lone figure continues to hit a shag bag of old golf balls. His tall, athletic frame casts a long shadow across the ground where his yellow lab Randy finds comfort from the late summer heat.

Bill Campbell is getting in one final practice session before the coming U.S. Amateur Golf Championship in Cleveland, Ohio. His swing is long and fluid, beginning slowly and then gaining momentum. The sound of his one-iron hitting the ball makes a distinctive “click” as it rushes skyward and lands some 220 yards away. He holds his finish and stands motionless for just a moment, his body in perfect balance. He continues to hit shot after shot with precision and consistency, each ball landing in nearly the identical spot. Finally, as darkness sets in, he grabs his clubs, collects all the shag balls and slips away with Randy by his side. Maybe this will be his year.

Much of Campbell’s life has been defined by golf. From his championships on the course to his countless contributions to the game, golf has played a significant role in shaping his legend as a sportsman. But there is far more to the man than the many titles he has garnered over his prolific career. Like his elegant golf swing, his life has been a study in balance.

Other than comedy icon Soupy Sales, perhaps no other name associated with Huntington is more widely recognized around the world than Bill Campbell. If you go to Google.com and search for “Bill Campbell + Golf” you will find some 646,000 hits.

He was born William Cammack Campbell in Huntington on May 5, 1923, at his parents’ home at 1030 13th Avenue. He was first introduced to the game of golf by his father at the age of 3.

“My mother, father, brother and I began a tradition of playing Sunday afternoons at Guyan,” says Campbell, a polite, soft-spoken man with a charming sense of humor. “We started as a foursome, but at some point my older brother would drop off to check out the girls at the pool, and I would drop off to check on him, and my mom would quit to check on us both. My father usually finished alone. But eventually I got hooked on the game.”

A child prodigy, his game flourished even though he never took a lesson. At 15, he became the second youngest competitor at the U.S. Amateur Championship. The youngest, at age 14, was one of Campbell’s heroes – the great Bobby Jones. At the prestigious tournament Campbell drew the attention of another golf legend, PGA pro Sam Snead, who took him under his wing and guided him through his formative golfing years. The two men remained close friends for 65 years until Snead’s death in 2002. Campbell was even asked to eulogize his old friend at the funeral.

After four years at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, he enrolled at Princeton University in New Jersey. The cold winters up north were not exactly conducive to his golf game, but Campbell was beginning to learn that there was more to life than golf. Receiving a quality education was more important to the young man than enrolling at a school in a warmer locale simply to play golf.

His studies were interrupted when he served in the U.S. Army during World War II. He entered as a private and came out as a captain, after serving in the artillery division in France and Germany and being awarded a Bronze Star for Valor.

He ultimately returned to Princeton where he received his degree in history in 1947. A career as a professional golfer never appealed to Campbell so the decision about his future was an easy one. He chose to follow in the footsteps of his idol Bobby Jones, the greatest player of his generation, and the only man to win the Grand Slam of golf and remain an amateur.

“I never wanted the life of a professional golfer,” Campbell explains while sitting amongst mounds of boxes and papers in his disheveled office in downtown Huntington. “I knew that wasn’t what I wanted. It’s so concentric. That’s a hard life. Instead, I’ve enjoyed a variety of pursuits. If you look around these walls, you will see I have many interests, not just golf.”

He also decided to return to Huntington and enter the family business. As such, Campbell became the fourth generation of his family to work for the venerable John Hancock Life Insurance Company. Over the years his agency would be one of the biggest producers in the nation for John Hancock; Campbell became the first lifetime member of John Hancock’s Most Prestigious Sales Leaders – a testament to his success and longevity in the world of business.

When he wasn’t working at his unassuming office on 11th Street, Campbell continued to play competitive golf. But the game he loved so much never came before work.

“I didn’t play weekday golf,” Campbell says. “In planning my career I wanted business and golf to be separate. I may play weekday golf when I’m away from Huntington, but when I’m here I generally haven’t done it.”

Despite his strong work ethic, he still managed to make his mark on the amateur golf record books. He captured championships in West Virginia, the United States and around the world. But the title that eluded him was the one he coveted most – the U.S. Amateur Championship.

Campbell threw his hat into the political ring in 1948 when he was appointed to the West Virginia House of Delegates after a local member resigned. During his three years there, he successfully sponsored a variety of bills, two of the most historic being the creation of Huntington’s Tri-State Airport and the introduction of voting machines in West Virginia. He then faced a string of political defeats, including a 1952 bid for the Congressional primary, which interfered with an invitation to play in the 1952 Masters. “Those were two of the worst decisions I ever made,” Campbell recalls. He eventually switched from the Democratic to the Republican party but lost a bid for the 1970 State Senate by just 179 votes. He never again actively sought political office.

Undeterred by his political defeats, Campbell continued to stay involved in public service by lending his time and talent to countless civic causes. Like his parents and grandparents before him, he served on numerous boards over the years in an attempt to move Huntington and the state of West Virginia forward. His father, Rolla D. Campbell, was a respected attorney and civic leader, while his mother, the former Ruth Cammack, was an accomplished pianist and hard-charging activist who cleaned up the county jail and took on the state’s mental health institutions almost singlehandedly. Drive around Huntington and you will see evidence of his family’s positive impact – Cammack Elementary School, the Campbell Woods law firm, the Cammack Children’s Center. Some of Bill Campbell’s civic contributions include roles as president of the Chamber of Commerce, president of the YMCA, membership in the Marshall University Foundation and a long-standing relationship with the Huntington Museum of Art.

“I chose my ancestors well,” Campbell says with a smile. “We have a history in Huntington of dedicated, civic-minded people. In fact, people are one of our state’s greatest resources. West Virginians are independent, forthright, industrious, honest, reliable and productive people.”

In 1954, at age 31 and seemingly a confirmed bachelor, he married the beautiful Joan Dourif, a widow with four young children. Overnight he left behind his single, carefree life to become a husband and father. In the following years the couple would have two children of their own. He handled it all with apparent ease. “Joan did all the heavy lifting,” he says admiringly.

A self-professed adrenaline junkie, Campbell is always on the go. Much of that drive stems from his personality as well as a lifelong commitment to fitness. He doesn’t drink or smoke, though he would gamble on the golf course – up to a $1 Nassau. He was a jogger and swimmer until age 70 when he switched to walking. In his younger days he was always trying out new exercise gizmos. All of this might explain how he won the long drive contest at the 1951 Masters with a 328-yard bomb. (Keep in mind that this was long before graphite shafts, titanium heads and today’s high-tech golf ball.) Even today at age 87 he can be found after hours at Huntington Physical Therapy, working on his strength and balance.

Both Campbell and his father shared a passion for aviation and received their pilot licenses in the same year. The pair often would fly together. Whether it was a weekend jaunt to Bill’s Greenbrier County farm or a carefree exploration of the West Virginia mountains, the father and son co-pilots shared numerous memories in the open skies.

If you ask any of Bill Campbell’s peers to describe him, they will undoubtedly refer to the qualities that distinguish him as a gentleman. They will also point out his unwavering character and dedication to the game of golf. As just one example, former United States Golf Association Executive Director Frank Hannigan likes to tell the following story:

I was talking with Jack Nicklaus about the USGA’s amateur status rules, including a prohibition against accepting free balls or clubs from equipment manufacturers. Nicklaus, who had turned professional by this time, was telling me the rule should be changed. He asserted that the prohibition was unenforceable.

“Name one top amateur who doesn’t take anything from the manufacturers,” Nicklaus said.

“Bill Campbell,” I replied.

Nicklaus paused for a moment. “Okay. You can have Campbell,” he said. “Name another one.”

Bill Campbell has always been one of a kind. He played amateur golf in the purest sense – as an honest, gentlemanly pursuit. He understood that golf is a game of honor, one that requires the competitors to keep their own score and call penalties on themselves. As Campbell says, “There is no other sport like it in the world.”

Unlike some of today’s professional golfers, he did not shout profanities or throw a club after a bad shot. He was gracious in victory and defeat, a sportsman in the truest sense of the word.

Off the course, Campbell is always the perfect gentleman as well, opening doors for others and standing when a woman enters the room. He takes the time to introduce a friend or guest to everyone around him, always has a kind or encouraging word for his friends and strives to find the best in others. These are just some of the reasons why people throughout the golf world refer to him as “the gentleman golfer.”

“He’s the consummate gentleman,” said Will Nicholson, a Denver banker and past president of the USGA.

“A Simon-pure amateur,” noted the late C. McDonald England of Huntington. “Some people say the only one left in the world.”

“He is warm, markedly courteous, sensitive to others and intelligent,” said former captain of the Royal & Ancient Club of St. Andrews Joseph Dey. “His service to the game has been unstinting.”

Ask Campbell what being a gentleman stands for and he gives the following answer: “Courtesy, caring, forgiving. Being interested in things bigger than yourself.”

Curiously, however, it was Campbell who counseled an unsure Jack Nicklaus to turn professional after the 21 year old captured his second straight U.S. Amateur Championship.

“Some of my friends at the USGA thought I was crazy,” Campbell recalls. “They recognized Jack could have been the greatest amateur of all time. But I wanted Jack to compete with the best players in the world, and at that time they were on the PGA Tour. And I wanted Jack to be in charge of his own life. I recognized he was a phenomenal talent and could do great things for the game of golf.”

The only negative thing people can find to say about Campbell is that he’s overly thrifty. His friends call him the “Frugal Scot” because he prefers old clothes, old cars and old golf balls. Amateur great and longtime friend Billy Joe Patton enjoyed saying that Bill Campbell was the only man ever to walk to the first tee at the Masters and ask where the ball washer was.

Bill Campbell arrived at the 1964 U.S. Amateur held at the Canterbury Golf Club in Cleveland, Ohio, feeling good about his game. Through the numerous rounds of the tournament he was playing well and catching some lucky breaks. “Maybe this will be my year,” he told his wife in confidence. But at age 41, time was running out for one of the world’s most accomplished amateurs. There was an array of young, talented golfers coming up the ranks he would have to contend with in coming years. But in a strange twist of irony, Campbell fought his way to the championship round only to be pitted against an old rival from West Virginia – Ed Tutwiler. The two had faced off numerous times in the West Virginia State Amateur Championship finals with Tutwiler, now 44, having won six of their seven encounters. “He had my number,” Campbell admits.

The two veterans put on a show for all the youngsters in the gallery as they battled back and forth over 36 holes, neither man giving an inch. Arriving at the 35th hole, a 215-yard par 3, the match was tied. Campbell’s usually reliable one-iron landed on the berm short of the green. Tutwiler, in turn, missed the green by 75 feet.

Tutwiler then pitched his ball to 15 feet short of the flag stick before two putting for bogey. Meanwhile, Campbell proceeded to chip up to three feet and roll in his par putt. For the first time in the match Campbell was now one up. When both players halved the 36th and final hole, the one title that Campbell had most desired – the National Amateur Champion of the United States – was finally his. It would prove to be his greatest victory in a long and storied amateur career, one that would open doors of opportunity for the rest of his life.

By the time he retired from competitive golf, Bill Campbell had amassed one of the greatest amateur résumés in history. It can easily be argued that he is the second greatest amateur golfer of all time, with Bobby Jones being the first. Over the course of seven decades he won 33 championships, including 15 West Virginia State Amateur titles, three West Virginia Opens, four North-South Amateur Championships, one U.S. Amateur Championship, one Mexican National Amateur Championship, two World Amateur Championships and back-to-back U.S. Senior Amateur titles. He was undefeated in singles matches in eight Walker Cup appearances for the United States and represented the U.S. in five America’s Cup team matches and three World Amateur team championships, one as a player and two as team captain.

He qualified for 37 U.S. Amateurs, 11 British Amateurs, 18 Masters and 15 U.S. Opens. All the more impressive is the longevity of his career. He is the only man to win both a USGA Amateur Championship and consecutive USGA Senior Amateur Championships.

For his countless contributions to the game of golf, he was elected president of the USGA in 1982 and 1983. Under his tenure, he tackled several important issues including overseeing the construction of a $10 million testing facility to study the technological advancements to golf clubs and golf balls and how they were impacting the game. He successfully pushed for the development of new turf grasses that were drought-resistant. But his most far-reaching and historic accomplishment was helping to merge the rules of the USGA and R&A.

In 1987 the Scotsman returned to his ancestor’s homeland when he became the second American to be named captain of the Royal & Ancient Club of St. Andrews, Scotland. In doing so, he became the first man in history to head golf’s two governing bodies. At first he commuted from the United States before deciding to rent a cottage in Scotland that dated back to 1480.

“Scotland was our Brigadoon,” he recalls fondly. “The experience had a profound impact on us. The people of Scotland are so friendly and genuine. Scotland and West Virginia are not very far apart.”

Campbell has been honored with numerous awards over the span of his career, including induction into the PGA Hall of Fame and the USGA’s highest honor – the Bob Jones Award for Distinguished Sportsmanship in Golf. Yet one of his proudest moments came more recently when he and the late professional golfer Julius Boros were named the 2003 Honorees of the Memorial Tournament in Dublin, Ohio – known by players on the PGA Tour as “Jack’s Tournament.” At the ceremony honoring the men, Jack Nicklaus made the following remarks:

“Just as Julius Boros impacted my life and career, so did Bill Campbell. Bill is one of the most decorated and distinguished amateur players in our game’s history, as well as one of its most respected administrators and statesmen. Bill’s place in my memories was secured early on when he took a keen interest in my career, beginning when I qualified as a 15-year-old for the 1955 U.S. Amateur. Bill Campbell helped me at a young age, and his support has continued ever since. Bill, thank you for what you’ve given me in friendship and guidance, and what you continue to give back to the game you so love.”

American writer Orison Swett Marden once noted, “Work, love and play are the great balance wheels of man’s being.” If that is true, then Campbell’s life has been one of ideal symmetry. Not merely a renowned sportsman, he is equally accomplished in his roles as husband, father, business executive, citizen, pilot, leader and ambassador.

Today, at age 87, his mind is still razor-sharp. While he can recall facts and dates from his past with ease, his gait is a bit slower and more measured. Even so, it hasn’t stopped him from traveling across the world for numerous obligations. But in the end he always returns to Huntington, his hometown, where he has worked in that messy office for the last 64 years. Over time his brother, uncles, aunts, cousins, children and grandchildren have all moved away. Even his wife prefers to spend most of her time at their homes in Hobe Sound, Fla. and Lewisburg, W.Va.

“Joan did it all for decades in Huntington, but with an empty nest she was entitled to a change in scenery,” Campbell explains. “She is an exceptional woman with deep literary interests.” Yet Campbell spends as much time as possible in Huntington – as much a fixture in the city as the river that runs through it.

“I’m here because to me it’s home,” Campbell says with that deep, soft voice. “I like to feel like I’m carrying on my family’s heritage. I like the friendliness of Huntington. I like the way people rally around you if you have troubles. It’s unusual. Most of the world moves at too fast a pace. I think those of us who live in Huntington have worked hard, but we still take time to be friends.”

Despite all the accolades and praise, he has remained modest, never forgetting his roots. In 1949 the West Virginia Open was set to come to Spring Valley Country Club in Huntington when tournament organizers approached Campbell with concerns that his longtime friend, Slammin’ Sammy Snead, was skipping the event. Campbell caught up with Snead at a golf tournament in New York and told him, “Do you know what they’re saying about you back home?”

“No, what?” Snead inquired.

“They’re saying that it’s gone to your head and you’ve forgotten where you came from,” Campbell said.

“Where is that tournament?” Snead barked. “You tell them I’ll be there.”

True to his word Snead played in the event, which he won.

Campbell has been the embodiment of amateur golf and what it means to be a gentleman. While the game of golf has changed and evolved over the years, Campbell has not. He still plays for the simple joy of the game – not the money.

“Golf is a game of misses and how you react to them. That applies also to life,” he explains. “We know that bad bounces and bad breaks occur in golf and in life. You don’t always get what you deserve. But we always hold out the hope that from a bad place, we might make a great recovery. Mistakes happen, and people are imperfect; but they can always try. The beauty of the game is that when you are through with a round, it’s gone, and tomorrow is a new day.”

History will most likely look back at him as golf’s last great amateur, the end point of a lineage that included the likes of Bobby Jones, Francis Ouimet, Chick Evans and Billy Joe Patton. But while Bill Campbell may mark the end of one era, hopefully the lessons gleaned from his distinguished life will carry on.