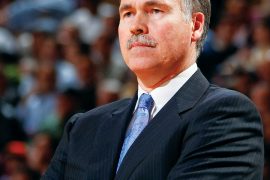

Possessing both vision and charisma, Greenbrier owner Jim Justice is a one-man marketing machine for all things good in West Virginia.

Interview by Jack Houvouras

HQ 72 | WINTER 2010

A mere 18 months ago only a handful of people had ever heard of Jim Justice, the highly successful businessman who made his fortune in coal, agriculture and literally dozens of other companies. But all of that changed on May 7, 2009, when he bought The Greenbrier resort out of bankruptcy for a mere $20.1 million. The big businessman, who stands 6 feet 7 inches tall, outmaneuvered Marriott Hotel Services Inc. to land the famed resort. Since then his notoriety has soared as the media began to learn more about the 59-year-old West Virginia native. Raised in Beckley, Justice earned both his B.A. and M.B.A. from Marshall University, where he was captain of the golf team. After graduation he entered the family business – coal. But Justice was determined to make his own mark, and, soon after joining the company, he initiated a foray into the agriculture business. He was extremely successful acquiring wheat, corn and soybean farms in four different states. Today, Justice Farms is the largest grain producer on the east coast. Upon the death of his father in 1993, Justice took control of the coal side of the business and under his leadership oversaw a tremendous expansion of the company before selling a portion of it in 2009 to a Russian company for $436 million. Today, Justice employs some 3,500 people at 48 different companies including cotton gins, Christmas tree farms, turf grass operations, golf courses, timber enhancement and land projects.

After buying The Greenbrier, Justice went to work immediately making several bold moves. He began by rehiring hundreds of furloughed workers and inking a new contract with the union. He opened an upscale steakhouse that he named Prime 44 West after his good friend and NBA legend Jerry West. Next, Justice announced plans to build an $85 million underground casino, and a mere 10 months later it was up and running. In addition to gambling, the Monte Carlo-style casino features high-end shops, a lounge and three world-class restaurants. While the casino was under construction, Justice brokered a six-year deal that would bring the first-ever PGA TOUR golf tournament to West Virginia. The Greenbrier Classic debuted on the Old White Course in July to rave reviews from players, fans and PGA officials. All of Justice’s decisions seem to be paying off. When he took over The Greenbrier the resort was averaging an occupancy rate of 30 percent. Today the resort is averaging 85 percent. Next on his list of goals is to restore the coveted Forbes (formerly Mobil) five star rating that the resort lost in 2000.

More than just a highly successful businessman, those who know him best describe him as a devoted family man. He and his wife Cathy have two children, Jay and Jill. Jay works in the family business and Jill is in her third year of medical school at Virginia Tech. Justice is also known for being profoundly generous with both his time and money. As just one example, he dresses up as Santa Claus every year and delivers $30,000 worth of gifts to the children of McDowell County in the state’s poorest region. He has coached basketball for the last 25-plus years, recording more than 750 wins. We sat down with Justice in his office at The Greenbrier to find out more about the multi-talented businessman who is quickly becoming West Virginia’s greatest natural resource.

How many hours of sleep do you get a night?

None (laughs). It would be easier to ask how many hours of sleep I get a week. But I probably get around four hours a night. It is what it is.

You own coal mines, corn, wheat, and soybean farms, a hunting and fishing preserve, Christmas tree farms, cotton gins, turf grass operations, golf courses, timber enhancement and land projects, Glade Springs Resort and, of course, The Greenbrier. Where do you find the energy to do it all?

Well, you know, I love what I do. And I think that’s the key to everything. If you’ve got a real passion for what you’re doing and you really enjoy it, you’ll be good at it. And if you don’t have that real passion, you should just go out and find a job. But you can still have passion in your work, and that passion will make your work fun. When you work as much as we work, you better be having fun at it. And I do have fun.

What are some of the highlights from your two years as captain of the Marshall University golf team?

Keeping [then-coach] Joe Feaganes out of trouble was surely a chore (laughs). I developed lifelong friendships with many of the guys that were on the team. There’s a lot of really good memories there. I loved Marshall and the camaraderie of the team.

You don’t see many 6-foot-7-inch golfers. Did you hit the ball a long way back then?

Long enough that a lot of times I couldn’t find it. I mean, I hit it a long way sometimes. To be perfectly frank, I played better golf when I was 16 than I did when I was in college. I was always real thin – it doesn’t look that way now – but I could really chip and putt. I really was great around the greens, and that’s where you score. When I got to college I started lifting weights and getting stronger, and I could hit the ball a mile; but I just seemed to fade away from either practicing enough or being confident enough in my short game.

What is your lowest round ever?

I’ve shot two 61s and one 62, but those were on little courses here and there around West Virginia, not competitively. I would say the best competitive round I ever had in a tournament was probably a 66. But that was a long time ago.

You were at Marshall University from 1970 to 1976, earning your bachelor’s and master’s degrees there. What was the sentiment on campus after the plane crash?

There aren’t many moments in your life where you know exactly where you were and what you were doing when you heard the news, but I do. I was on the third floor of South Hall (now Holderby Hall) in my dorm room. It was 10 p.m. when we heard about the crash. It was drizzling rain outside. I knew a lot of the players and the people that were on the plane. Gene Morehouse was a really close friend of my family. It was bad. It was a tough time.

What did you think of the movie We Are Marshall?

I loved it. I thought it was great, I really did. I thought it captured a lot of those moments of truth and the rebirth of the university.

Who was your favorite professor at Marshall?

Dr. Robert Alexander. At the time he was the dean of the business school. I’ll never forget when I first transferred to Marshall, I had him for Principles in Management. He walked into class, opened his grade book and said, “The last class we had here made 22 As, 18 Bs and one C.” And I’m thinking, “This is going to be a piece-of-cake class. This is just what I wanted.” And then all of a sudden he peered out over his glasses and said, “If you can’t make an A or B in my class I don’t feel like I’ve done my job – but you better buckle up, because I’m getting ready to work your ass off.” That was the way he was. He worked you hard, but he was a really good teacher. I carry that with me today.

Do you have a favorite memory from your time at Marshall?

Well, Marshall is where my wife Cathy and I fell in love. Actually, she’s the reason why I ended up at Marshall. We started dating one summer while I was attending the University of Tennessee. She was at Marshall, and I started thinking, “Maybe I’ll transfer. This will be neat. I’ll be closer to home, I’ll be dating this girl and I’ll be able to hunt and fish more.”

What were some of your favorite hangouts in Huntington?

Other than the Varsity, I went to Wiggins restaurant more than any other place there. Another thing is that I love to hunt and fish, and I love the outdoors. The great thing about Huntington is that it never gets too cold. You’re right on the river, and in the middle of winter I would be duck hunting or quail hunting somewhere all the time. In fact, I had a bird dog that I kept with me in my apartment. Her name was Lady, and she was my best buddy.

If you were running Marshall as a business, what would you focus on?

Well, I know this may not be the most popular answer, but (pauses) I think in today’s world, from a business standpoint, it’s imperative that you have a terrific sports program. It really is your public relations appeal. Obviously the importance of academics is paramount and that’s really why you go to school – to get an education. But athletics are really important from a marketing standpoint. When you have strong athletic teams, you’re in the limelight all the time and you have the ability to attract students from across the country. For good or for bad, that’s a major factor when someone chooses a school. I really, truly believe that Huntington is a wonderful location for the university. To me, it’s our state’s premier city. So, with that being said, Marshall has all the appeal. But again, we need the national exposure that a winning football or basketball program can bring.

Were you at the MU vs. WVU game this year?

I was not, but I watched every minute of it on TV. The overtime loss was tragic. It was absolutely tragic. There aren’t many sporting games that upset me so much that I carry them with me for days, but that sure did. That was just terrible. But I’m a supporter of WVU, too. I really am, because I want all of our universities to succeed. I want the whole state of West Virginia to succeed.

What’s more challenging, running a coal company or coaching teenage girls?

I always tell my teens this: “You know, I can run one of 48 different businesses and make mistakes, and those mistakes turn into failures. And when that happens, you can regroup. But I’m not going to stand in front of 2,000 people and watch us lose a game and screw up.” So from that standpoint, it’s tougher coaching basketball because everybody sees you fail. I really take coaching seriously, and I put a lot into it. But as far as the challenge of teenage girls, our kids are good. They don’t get into trouble – at least not with me.

What do you love most about West Virginia?

Its people. I love the people. We are all the things I want to be myself. We’re humble and we’re loving and we’re appreciative of others. A lot of people just take you for granted, but West Virginians are genuinely an appreciative people. And a lot of people will give you a big smile and not mean any part of it, but we’re the real deal. The people of West Virginia are good, but they’ve been beat down. My biggest objective is to help the people of West Virginia be proud of their state. And I want the world to see how good we really are. To me, that is worth everything.

Many people in the state did not know your name before you purchased The Greenbrier. But you seem to be a natural promoter and creative thinker. Are these traits you have always possessed or have you had to learn them over the last two years?

Oh no, I’ve been that way forever. I’m no different now than I was 20 years ago. What you see today is the same person you’ll see tomorrow.

Was buying The Greenbrier a business or sentimental decision?

It was both. If you look at being able to buy The Greenbrier for $20 million – I mean, come on. The golf courses here alone are worth $20 million. But what I also bought was somebody else’s nightmare because it was losing money like crazy. When you get your arms around it, all of a sudden you’ve got a whole new dinosaur, and it’s whipping you for $3 million a month and you can’t seem to turn it around. You’ve got to be a big boy to be able to do that. The challenge of turning it around is one of the great reasons that I bought it. The other side is that I grew up in really humble beginnings. My grandmother and grandfather on my mom’s side never had indoor plumbing. My dad was the only child in a little coal camp house. We couldn’t afford to come here when I was a young kid, but it was always instilled in me that The Greenbrier was our state’s treasure, our national treasure. When you believe that, coupled with the fact that you’re coaching girls on a basketball team whose parents and aunts and uncles work over here, and they’re having all kinds of trouble, you’ve sure got a sentimental reason for buying it.

How will you turn a profit at The Greenbrier?

Well, we’re doing it. We did it first and foremost with a lot of hard work. You see, everybody said to me, “How are you going to run this? You’ve never been in the hospitality business before.” But to me, it’s just not difficult at all. I know how to appreciate and be kind to people. My MBA specialization was marketing and advertising. It was just a matter of infusing all kinds of energy back into this place, and we did that with Jerry West’s restaurant, the Italian restaurant, the casino, the golf tournament and everything else. And we’ve created a real positive buzz. We’ve gone from occupancy levels of 30 percent to occupancy levels of 85 percent. We’re doing things that some people think would’ve never been possible. We’ve got it headed in the right direction.

Why is the new casino such an important aspect of The Greenbrier?

I don’t know if the casino will ever make money. In fact, it’s lost money every month that we’ve had it. But it is a tilt factor for whether or not somebody’s going to come here. If you are making a choice between coming here and going to another nice place that doesn’t have a casino, even if you only want to go to the casino for two hours one night, it kind of tilts your decision our way.

You are still in the coal business. In what direction do you see the industry going, in light of the American people’s ongoing concerns about the environment?

As I said earlier, I love to hunt and fish and to be outdoors. I am genuinely a true lover of nature and our environment. But I can tell you that it is absolutely impossible for us to think we can do without coal. Fifty percent of America’s electricity comes from coal. Really and truly, we do have to solve the environmental challenges. But for us to come up with some idealistic belief that today we can stop using coal, or today we can drastically reduce our use of coal, all we’re going to do is blow our legs off from an economic standpoint. China would own us. Their economy is growing like crazy. Here, we’ve got people out of jobs, and we keep doing things that are just playing into their hands. They’re owning more and more of our debt, and it’s just frivolous to think that while China builds one new coal-fired power plant every week, we’re going to completely change the world on some belief that we can step forward and be the leader in all climate change. We absolutely need to be addressing climate change and environmental concerns, and wean our way off of the fossil fuels in time, but we can’t even think of doing that today. Naturally, we have to move away from our dependence on foreign oil. I truly believe there are real possibilities in clean coal technologies.

What made a coal man decide to get into the agriculture business?

Well, my dad and I were best buddies. We worked side by side. He was my best man in my wedding. Gosh, I miss him more than good sense. But you know, he loved to be able to run his side. So, he ran the coal side and I began building up the agricultural side. We helped each other, but for 20 years I was a farmer. (Laughs) And I got pretty good at it, too. Also, if you were to pick two industries in the 1970s that were industries you felt could make a difference – agriculture and energy were two very good choices.

What are three things your father taught you that have made you a better person?

When I was 18, my dad gave me a job to do and things went badly. He summoned me to his office and I recall standing in front of his desk in silence. I remember looking at him. He had played football at Purdue and his arms were as big as my legs. I then said to him, “Dad, there wasn’t anything I could do.” All of a sudden the entire desk exploded and he jumped from his chair, grabbed me by the shirt and said, “There’s always something you can do, and you better damn well always remember that.” That was my dad. He believed if something was really tough, it’d take a couple of days, and if it was impossible it would take another day. That’s what he believed. Also, my dad would never, ever say anything bad about somebody else. He would belabor the fact that if you don’t have anything nice to say you shouldn’t say it. And he had this saying: “Don’t expect more than you can inspect. If you tackle a job and aren’t there inspecting it, don’t expect it to be good.”

I noticed that you were smiling in all the photos from The Greenbrier Casino’s grand opening, but you looked especially happy in the photos with Jessica Simpson. Can you explain that?

(Laughs) I don’t know if we ought to go in a lot of detail about that. I’ll just say that Jessica Simpson was great and really, really pretty. It was a very exciting evening.

Is The Greenbrier the biggest gamble of your life?

(Pauses) No, I don’t think so. I don’t think so at all. We’ve bought properties when we didn’t have a lot of excess cash, and there have surely been agricultural ventures or coal ventures or timber ventures that, to be perfectly honest, were a lot riskier than owning The Greenbrier. Don’t get me wrong, if you don’t run it right it will bite you, but that’s the same with everything we do.

You seem very confident.

No, I’m not really very confident at all. I’m simple. The first thing in my life is the good Lord, second is my family, then my employees and finally the kids I coach. That’s what I focus on every day. There’s nothing real fancy about me. I’m surely not confident; I think people who are really confident are just setting themselves up to get whipped. Right as soon as you think you’re the toughest guy on the block, you’re gonna get it. You touched on the very thing that people really don’t know about me, and that is that every day, with every decision, I sit back and say, “Who are you kidding? Do you really know what you’re doing here? Is this really going to work out?” I’m the guy who’s double-checking, quadruple-checking and doubting myself all the time, but I don’t let the world see it. I really believe that those who don’t doubt themselves are going get themselves in a lot of trouble.