This year marks the 65th anniversary of Gen. Chuck Yeager’s breaking the sound barrier. We sat down with the living legend to get his thoughts on making history, modern aviation, his scholarship program at Marshall and the challenge of slowing down for a man who as lived life at full throttle.

Interview by Jack Houvouras

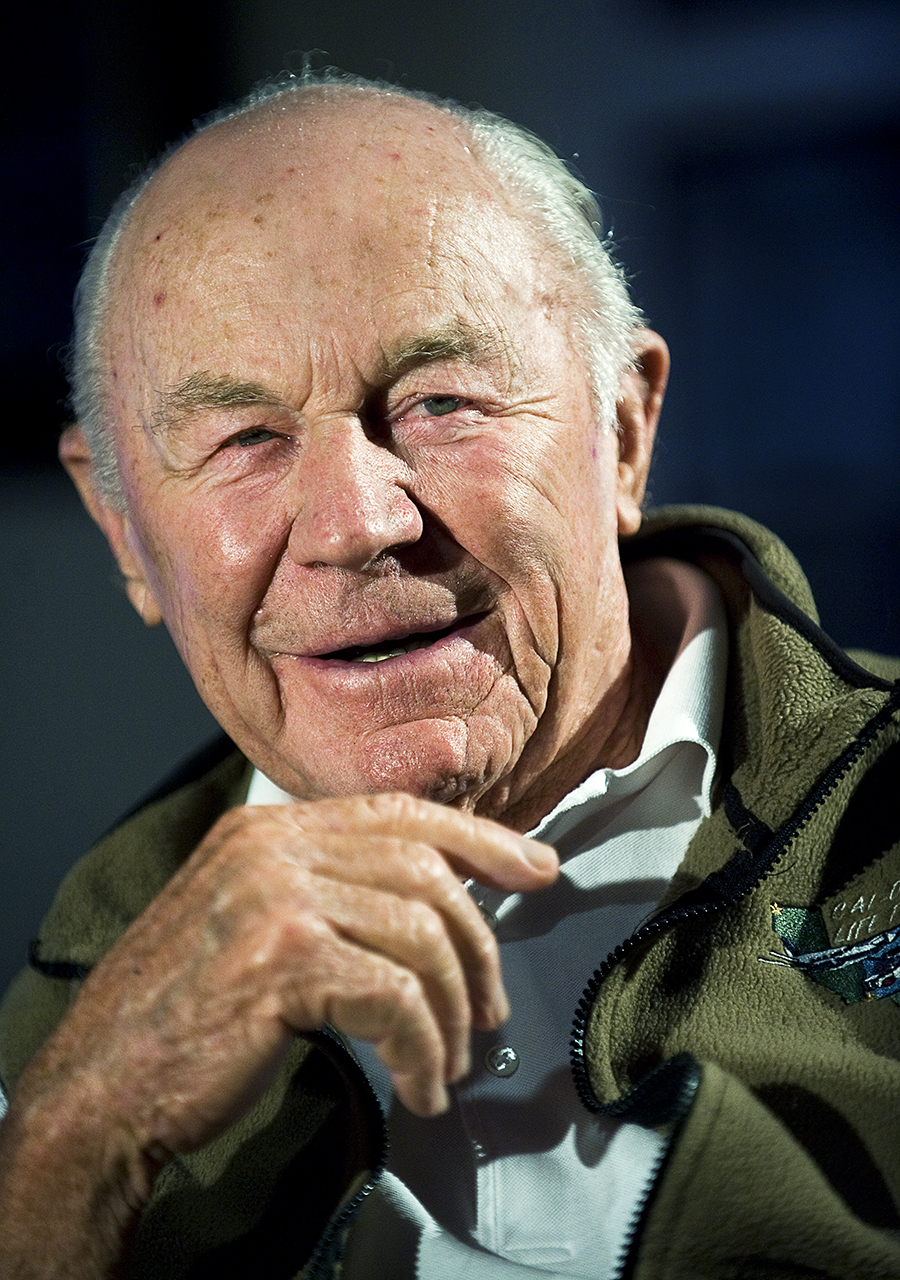

HQ 77 | SPRING 2012

Having just turned 89, Brig. Gen. Chuck Yeager shows few signs of slowing down, but that shouldn’t come as a surprise to the aviation icon once known as the first fastest man alive. The Hamlin, W.Va., native earned that title on Oct. 14, 1947, when he did the unthinkable and broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1, which he named Glamorous Glennis after his first wife. Yeager’s feat ushered in America’s race for space and forever changed the world of aviation.

But Yeager’s life’s work includes far more than smashing through that brick wall in the sky. Before he became the best test pilot in the business, he was the best dogfighter in the military, cruising the skies over Germany and France in his P-51 Mustang, shooting down scores of enemy planes during World War II. While most pilots dream of becoming an “ace” during times of war, Yeager accomplished that feat in just one day, shooting down five German planes and becoming the nation’s first “ace in a day.” While the United States military turned out scores of great pilots, not one was as gifted as the kid from West Virginia.

“When Yeager attacked, he was ferocious,” noted fellow fighter pilot Bud Anderson. “Yeager was the best. Period. No one matched his skill or courage or, I might add, his capacity to raise hell and have fun.”

As just one example of his capacity to raise hell, Yeager decided to drop in on his hometown of Hamlin during a military flight back east. At approximately 7 a.m., he hit full throttle and dived toward Main Street at 500 mph before pulling up, doing some slow rolls and buzzing the treetops. An elderly lady was so frightened that she had to be taken to the hospital.

Yeager went on to become the greatest test pilot in the game, flying experimental aircraft for the United States Air Force and breaking numerous speed and altitude world records. It was Yeager and his brethren who did the leg work for what would later become NASA.

Yeager was already a household name when writer Tom Wolfe released The Right Stuff, a book about America’s test pilots and the Mercury Astronaut Program. Wolfe’s book and later the movie by the same name would make Yeager a bona fide star. As Wolfe saw it, Yeager was the measuring stick by which all pilots, and later astronauts, were judged. He was the best of the best.

Yeager had such an impact on aviation that he actually began to change the way pilots spoke. It was his coolness under pressure combined with his distinctive West Virginia drawl that transformed the dialect of an entire generation of pilots.

“That voice,” Wolfe writes, “started drifting down from on high. At first the tower at Edwards (Air Force Base) began to notice that all of a sudden there were an awful lot of test pilots up there with West Virginia drawls. Military pilots and then, soon, airline pilots…began to talk in that poker-hollow West Virginia drawl. It was the drawl of the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff: Chuck Yeager.”

From a lowly private in the Air Force to brigadier general, from the best fighter pilot in World War II to the man who broke the sound barrier, today Chuck Yeager is considered the greatest pilot who ever lived. For these reasons and more, many consider him to be the most accomplished man in the history of West Virginia. We caught up with the living legend recently to see how retirement and his marriage to Victoria D’Angelo (his first wife Glennis died in 1990) were treating this good ol’ boy from Hamlin. As you will see, he’s still raising hell and having fun.

Are you still flying these days?

You bet. I broke the sound barrier in an F-16 on October 14 of last year, and I was down at Edwards just last month flying M-16s. I also still fly light stuff every once in a while.

During World War II, you flew P-51 Mustangs in combat. Do you still get a chance to fly the P-51 every once in a while?

I haven’t been in the 51 for about a year. I just haven’t had the opportunity. They’re getting few and far between, and the guys who have them are hanging on to them pretty close.

What have been your favorite planes to fly over the years?

I’ve flown 360 types of models of mostly military airplanes in my career, so I obviously can’t answer a question like that. There’s the X-1, of course. But in World War II, I enjoyed flying the P-51 because at that time it was the best fighter we had. Then in Korea I flew F-100s, B-57s, F-102s and F-86s, and I really enjoyed flying those. In Vietnam I flew F-4s for more than 100 missions. I was in Pakistan for two years, flying with the Pakistan Air Force, and I flew French fighters and Russian fighters there because those were the planes flown by the Pakistanis.

Do you ever get nervous when you fly in a commercial airplane?

No, I don’t worry that I’ll arrive at the scene of the accident first, if that’s what you mean. (Laughs) There’s nothing safer than the commercial airlines. Those pilots are well trained, and all they do is fly one airplane day in and day out.

You were in your hometown of Hamlin in December visiting some lifelong friends. How has Hamlin changed since your childhood?

Well, the population may have increased by 10 percent or so since I left in 1941 (Laughs), but the town really hasn’t changed a hell of a lot. In the old days, the industrial part of the town focused on natural gas drilling, and there was a lot of farming – and that hasn’t changed. The high school has gotten much bigger, but it seems like the kids don’t go out and play much. They don’t seem to get much exercise anymore.

How did you become associated with Marshall University and its most prestigious scholarship program, the Society of Yeager Scholars?

Well, that was Glennis’s idea. She helped put it together in 1986. We visited Marshall University and talked to them about forming the Yeager Scholars program, which would be a scholarship based upon private donations. I was very adamant that there would be no political influence in appointing Yeager Scholars. I told them, “If I ever see that happen, I’ll walk away from it.” And they’ve kept it pretty honest. The kids are interviewed by a board of teachers, and they only pick the best. They also only pick the number of kids that the foundation can support; it’s usually around 11 or 12 students. The kids get four years of education and get to study at Oxford University in England. And when they graduate, they’re very highly thought of. They’re really sharp.

Do you interact much with the students who are chosen?

I visited the Capitol a month ago to talk to the new class of Yeager Scholars; I always try to talk to each new class. But I think the people who ask the most questions and who are the most interested in talking to me are their parents and grandparents. (Laughs) They’re more my age, you know.

What advice do you give the Yeager Scholars when you speak to them?

It’s pretty simple. I don’t give anyone advice; I just give the same message: “Those who do it on their own are the best. You can’t just hope that success will be handed to you on a silver platter.”

This year marks the 65th anniversary of your breaking the sound barrier. What is your favorite memory from that day?

Well, I was just doing my duty. You know, I’ve flown hundreds of aircraft for the United States Air Force, as well as other air forces all over the world, but looking back on the X-1, it was probably the biggest breakthrough that has ever occurred in aviation. When I got the X-1 above Mach 1, I knew that was the moment we had opened up the universe. From then on we could get into space.

Sixty-five years after breaking the sound barrier, how do you view today’s advances in aviation? Where do you see aviation in the future?

You can’t really predict that. Aviation responds to demands. If you have a war, technology advances very fast. If there’s no war, technology stays pretty stable. When we got the Bell X-1 above Mach 1, it took the British and the French and the Soviet Union five years to catch up with us on the supersonic technology we uncovered. That really impressed me. But then the X-1 was just the first; after that, there was the X-2, then the X-3. From there, we got into space.

How’s your exceptional 20/10 vision these days?

It’s still pretty good. These days, I go between 20/15 and 20/20, and obviously I don’t wear glasses for reading or anything like that. I’m lucky because it’s primarily hereditary. I remember my mom lived to be around 90 years old, and she’d still pick up a newspaper and read it without glasses.

Would you say your eyesight is what made you such a good hunter and a great dogfighter?

Yes, because during World War II there was no radar. To pick up the enemies back then, everything depended on your eyesight and visual acuity. When I was flying I could spot the enemy from 25 or 30 miles away. That’s a lot farther than the other guys could see, so it made it easy to maneuver my squadron. I’d angle my squadron so we’d come in out of the sun, and the enemies wouldn’t see us until we were on top of them. Today, of course, everything is done with radar. Technology has advanced so much and communication is so good that everyone knows everything that’s going on.

You turned 89 years old in February. How did you celebrate the big day?

I didn’t want to celebrate, but Victoria made me. (Laughs) I did get to introduce the Oak Ridge Boys in Laughlin, Nev. The Oak RidgeBoysarereallygood friends. About 50 years ago, I was down in North Carolina for a reunion with a fighter group, and this guy came over and invited us to the Oak Ridge Boys’ show.

I asked how much it would cost, and the guy said it was free for us. So I said we’d love to come over and see the program; I knew they were a really good quartet. Well, they put us on the front row and dedicated the show to us. Afterward, they invited us backstage, where we met all the guys in the band. Since then, I’ve probably introduced them 25 or 30 times at concerts all over the United States. Whenever we’re in the same area, I make an effort to go introduce them. They are really patriotic, and they’re wonderful, wonderful people. They’re my kind of music.

Do you still make your annual two-week trek to the High Sierras every June to fish for the elusive golden trout?

No. Victoria and I went up there four or five years ago and it took us three days to get where I used to go. I finally said, “I’m getting too damn old for this.” Now I go up to Alaska and fish. There’s nothing in the world like the salmon fishing in Alaska. It’s just wonderful fishing. In May, you get the kings, then in July, you get the reds. In August and September you get the silvers, and then the rivers freeze over. It’s good fishing, and it’s the same every year.

Do you still hunt?

Yes. But I’m a meat hunter, not a trophy hunter. I don’t collect horns or shoot big game or anything like that. It’s like back home in West Virginia, when I was kid, we’d shoot squirrels and rabbits, but it was for the table. I come back to West Virginia to hunt in December, when the governor hosts his annual one-shot doe hunt. The governor opens up the season for does only, and each hunter is allowed to shoot one doe. I think last year we killed around 170. All the does are sent over to the meat processing guys who donate their time for free; those guys dress and package the meat and then give it to the poor. It’s a really wonderful program, and I’ve participated in that for the last four years.

Where are some of the best places in the world you have hunted?

Probably Germany and Pakistan. The hunting in Germany is the same today as it was 1,000 years ago. Everything there is protected and controlled; they manage their forests and their game really well. The traditions haven’t changed. You read a lot about the big game hunting in Africa, but that really wasn’t my favorite place. I went down there about three months ago, and some of the guys from the South African Air Force took me out to harvest the game that wasn’t good enough to sell to the trophy hunters. It was interesting, but it was so easy. It’s nothing like here in the U.S., where you have to stalk game.

What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever had to stalk and hunt?

Elk are probably the toughest here in the United States. They’re very smart, and they live in very rough country.

Tom Brokaw wrote a book in 1998 that describes the people who lived through the Depression and went on to fight in World War II as “The Greatest Generation.” Do you think that’s true?

Well, naming the greatest generation is kind of like naming “the greatest pilot.” There are pilots all over the world who may be great, but they’ve never been able to demonstrate it because they have never had the opportunity to prove their skills in combat. Most guys are named heroes in times of war, when they receive various awards. You’re rarely given the chance to demonstrate your greatness or superiority except in war. Sure, you can do research flying like I did for nine years at Edwards, but I also fought in four wars, survived those four wars – and did very well in those four wars. So, to be the greatest at anything you have to be given the opportunity to demonstrate your capabilities under the most trying circumstances, and my generation certainly did that.

What would you say is one quality all great pilots possess?

Experience. I’ll tell you this: I flew with the Pakistan Air Force for three years, during the war with India, and I’d say the Pakistani pilots are the best I’ve ever flown with in my life. And it’s because they’ve got a lot of experience. That’s what makes a good pilot. The pilot with the most experience is the best. And if he’s gotten that experience in wars, he obviously has to be damn good, or else he’d be dead.

In the movie The Right Stuff, it is implied that you were never a candidate for NASA’s astronaut program because you did not have a college degree. Is that true?

Yes, that’s true. But I also didn’t want to be “spam in a can,” as my generation used to say. That was a phrase we all used in the Air Force back when NASA was forming; we’d say we didn’t want to come out smelling like that ham they sent up in space first. (Laughs) We’d either say that or we’d say, “I don’t want to sweep monkey crap out of my seat before I sit down.” But here’s something you may not know: back in 1960, the Air Force was responsible for space. We oversaw the space program, and NASA didn’t exist. My job was commandant of the astronaut school, which was attended by military test pilots. We had a budget, a miniature space station program and vehicles designed that we would send into space and maneuver. I ran the school from 1960 to 1966. In 1965, ol’ LBJ (President Lyndon Baines Johnson), along with a lot of other political types, said that if the U.S. could keep our military out of space, it would keep the Russian military from building weapons in space. It was a dumb idea, but it was the feeling of the U.S. at the time. So they formed NACA – the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics – and later called it NASA – the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. And in 1965, they transferred all the responsibility of space training to NASA. As commandant I felt very bad about that decision; I thought we managed the program a hell of a lot better than the bureaucracy of NASA has done over the years. NASA wastes a hell of a lot of money. From the school I was commandant of, 26 of our graduates went into space as NASA astronauts – and that’s something the military was responsible for entirely. But the bureaucrats got involved, and it’s been a mess ever since.

You were an adviser during the filming of The Right Stuff and even made a cameo appearance in the movie as a bartender at “Pancho’s Place.” What did you think of that experience?

It was fun. I did all the flying. The director, Philip Kaufman, did a pretty good job, and we had a pretty good cast. The special effects were also exciting. I’ve played in two or three movies, and it’s interesting to watch how these guys put stuff on film. What The Right Stuff did was show you how much the Air Force did for NASA to keep it going. There were guys who were killing themselves doing research for the NASA program.

You have traveled around the world through your work in the military and years later through speaking engagements. What are your favorite places on earth?

I’d say my favorite trip was my first trip to Germany; I was there for a three-year period as a commander. I hunted and got to be friendly with the jägermeisters, the hunting guys. Germany’s forests and game really impressed me, and of course the Alps are beautiful. I fished a lot in New Zealand, and it was beautiful, too. And I spent three years in Pakistan – a very interesting country. But you know, every place I’ve been has its own beauty.

You once said that the hills of West Virginia were the prettiest things you had ever seen until you flew over the High Sierra Nevadas in California.

Yes. And the reason for that is because the High Sierras are 400 miles long and 80 miles wide, with mountains that go up to 14,400 feet. It’s a national park, so there are no roads and no buildings, and it’s wild. It’s controlled, too; they don’t allow vehicles, and the only way you can get through it is with a backpack. It is really a beautiful part of the country. I used to go every year around June, right when the snow melted.

Is that why you ended up retiring in the foothills of the High Sierras?

Yeah, but by the time I retired I was too old to do anything that adventurous. (Laughs)

You have always been a proud West Virginian and a great ambassador for the state. What makes West Virginia so special?

It’s where I was born, so it’s special to me. It’s a beautiful state, and the people there were raised right.

Tell us about the General Chuck Yeager Foundation you recently founded.

The founder of USA Today, Al Neuharth, started a program called the Free Spirit Award. He took a million dollars and divided it up four ways and gave it to four people with “free spirits.” To him, those four had “the right stuff,” and I was one of them because of what I did breaking the sound barrier. Victoria and I decided to start a foundation, which we would use to help support Marshall University and the Yeager Scholars. We also support Disability Resources Incorporated down in Abilene, Texas, which helps kids with Down syndrome.

Your wife Glennis passed away in 1990, and in 2003 you married Victoria D’Angelo. How has she impacted your life?

Victoria is as smart as a tack. She fills in the voids that I have, especially in the business world. You know, I spent my life in aviation, so when it comes to other things, I’m lacking a little bit. She really can handle just about anything that comes up. That’s the way she’s managed our lives. And she’s a hell of a shot with a rifle. She’s shot quite a few elk, and she’s good with a shotgun, too, for pheasants and quail and things like that. She loves to fish, so she goes to Alaska with me. She fishes for salmon with the fly rod, and she’s damn good. And she’s a good pilot. You know, very few people fly formation, where you’re just 10 feet from another airplane.

I taught her to fly formation, and she does it well. She also flies the way good pilots are supposed to fly. You’re supposed to use a checklist, and you’re supposed to follow certain rules. These are things most pilots don’t do all the time, but by God, she’s meticulous about doing it.

You do a lot of traveling for a “senior citizen.” Last year you traveled to France, Spain, South Africa, Nevada, New York City, Alaska, Mexico, California, Hawaii and the Middle East. Do you ever think about slowing down?

Well, I’ve slowed down a hell of a lot. You have to slow down when you get old. I just turned 89 – that’s damn old. I don’t go to the High Sierras anymore. And when I go out hunting, I don’t run across the hills; I drag my feet. (Laughs) You can’t do all the things you did 50 years ago, obviously.

In your autobiography Yeager, you wrote, “I’ve had a full life and enjoyed just about every damned minute of it because that’s how I lived.” Is that still true?

Hell, yeah. I’m still enjoying every minute.

What role did the Air Force play in making you the man you are today?

As a kid I was taught to honor my flag and my country, and that’s the way I’ve lived my life. But let’s put it this way: what I am, I owe to the Air Force. They took an 18-year-old kid out of the hills of West Virginia with a high school education, and they taught me everything I needed to know.

I also had the opportunity to take advantage of what they offered. But yes, that’s what I’d say – what I am, I owe to the Air Force.

How would you like to be remembered by future generations of Americans?

I just want to be remembered for living. Hell, everybody has to die. You just live your life, and if you’re at the right place at the right time, you accomplish something, and people remember you for it. Breaking the sound barrier will probably be how most people remember me. But I’m just lucky. If I hadn’t been flying that airplane, and if I hadn’t become a pilot, I probably wouldn’t be remembered for anything. I was given the right opportunity, and I took advantage of the duty that was given to me.