A look back at Marshall’s forgotten All-American

By Keith Morehouse

HQ 81 | SPRING 2013

The setting inside Herb Colker’s office at West Virginia Electric contradicts what you’d think his workplace might look like. At 92 years old, he still comes to work six days a week. Colker’s brother and uncle founded the company back in the 1930s, and it was as the country was digging out from the Great Depression that Herb Colker came to Huntington to begin his career. It was pure happenstance that he would take interest in Marshall basketball and, in particular, the talents of a meteoric guard by the name of Jules Rivlin.

“I watched him and saw the fast break and it was wonderful,” Colker remembered. “He was one of the early one-hand shooters. Cam (coach Cam Henderson) was a great coach and ‘Riv’ just soaked it up. He was one of most likeable people you’ll ever meet, and he really, really knew basketball.”

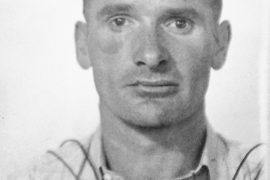

Rivlin is recognized by many longtime Marshall hoops junkies as the man who coached Hal Greer, but Rivlin’s story deserves far more scrutiny. Behind those grainy black and white pictures is a fascinating tale of a man who could run like the wind.

Julius Rivlin was born in Pennsylvania but grew up in Wheeling, W.Va. He was a star athlete at Triadelphia High School and named All-State in basketball in 1935. He was the top scorer at the state track meet when he won the 100-yard dash in a blazing 10.2 seconds and won the 220-yard dash with a time of 22.8. The University of Pittsburgh offered him a scholarship to run track, but he wasn’t quite ready to put his basketball away. He knew the only way he could continue his athletic career in college was if someone else paid for it.

“In a hundred million years Rivlin couldn’t have gone to college,” Colker said. “There wasn’t a dime in the family.”

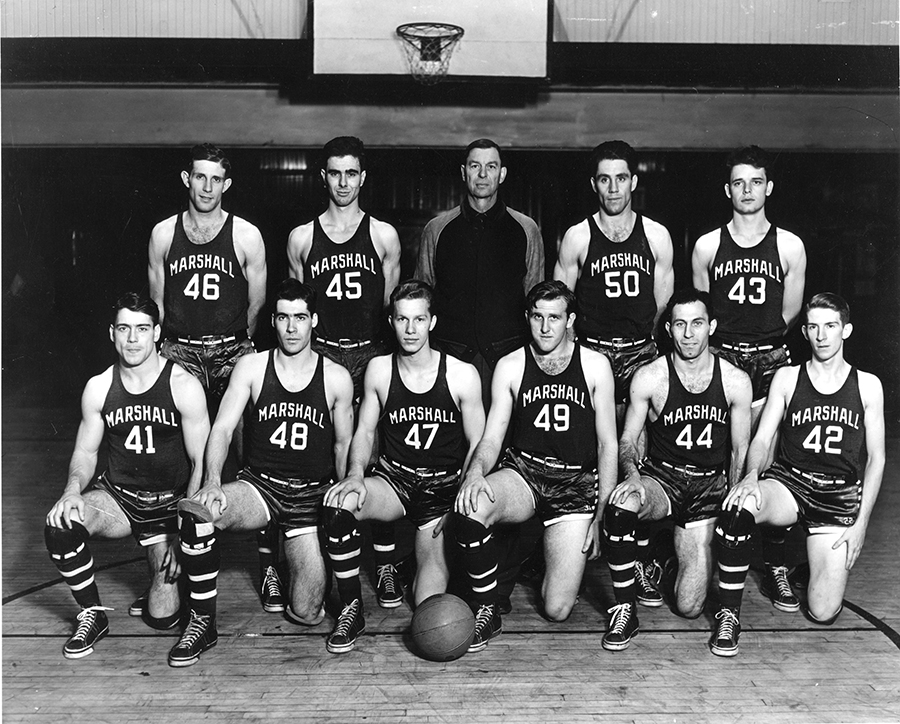

Rivlin looked south to Huntington where a third- year coach at Marshall by the name of Cam Henderson had put together a 23-8 record in the 1936-37 season. Henderson had just begun to fine-tune a style of offense that was predicated on having a speedy ball handler who could lead “the fast break.” Rivlin flourished in Henderson’s system, scoring 1,093 points in his career. In 1938 he finished second in the nation in scoring. Rivlin’s teams finished a three-year run winning 75 games and losing only 13. In 1940, he would become Cam Henderson’s first All-American when he was named to the Associated Press Little All-American Team.

One of Rivlin’s teammates on that 1940 team was Jim Treacy. When Rivlin returned to Marshall as head coach, Treacy’s son Bill played for him. Bill Treacy recalls the story his dad told him about Rivlin’s last home game. Coach Henderson was substituting Jim Treacy for Rivlin one last time.

“He went in for Rivlin,” Bill Treacy said with the hint of a smile in his voice. “He later told me, ‘I got a tremendous ovation.’” Knowing, of course, that the ovation was for Rivlin coming out, not for Treacy going in.

After he left Marshall, Rivlin was drafted by the Akron Wingfoots of the old National Basketball League, the precursor to the NBA. During the 1940s, Rivlin was something of a basketball vagabond, playing on service teams and then back in the NBL with the Toledo Jeeps.

In the mid ’50s, Rivlin was minding his store, the Jules Rivlin Sports Shop, when the opportunity to succeed Cam Henderson presented itself. Rivlin’s respect for Henderson was apparent in an interview with former Herald-Dispatch reporter and nationally syndicated sports writer, Lou Sahadi.

“The only two things Cam required of his players were discipline and respect,” Rivlin told Sahadi. “I never saw someone so prompt in his actions. We all had a quiet, sort of fearful respect for his coaching ability.”

Rivlin inherited a talented squad in 1955-56. His team won the Mid-American Conference championship and went to the NCAA tournament, seamlessly using the system Henderson had taught him.

“He was one of the first guys who told me how to run the fast break,” Hal Greer remembered on a visit to Huntington last year. “Push the ball out in front of you, stop at the foul line, shoot the ball or give it left or right.”

Rivlin was all about opportunity for his players. His friendship with Syracuse Nationals coach Paul Seymour was instrumental in helping to get Greer picked by the Nationals in the NBA draft. Former player Sonny Allen credits Rivlin with teaching him more than just basketball.

“Without Jules I probably wouldn’t have gone to college,” Allen said. Allen was an ultra-successful college coach in his own right who won 424 games at three schools. “At the time he kind of let you play. It was a players’ game; now I think coaches have way too much influence.”

“We had a distinct advantage over many teams,” NCAA record-holding rebounder Charlie Slack recalls. “We were so well conditioned. We didn’t have many set plays. If I wanted to improve my stats in the box score, I had to chase it and go get it.”

Rivlin won 100 games at Marshall. His coaching career ended in 1963, and he died in Los Angeles in 2002. Gone, and unfortunately forgotten by some.

Above Herb Colker’s desk are pictures of his wife and kids, daily reminders of a life well lived. He’s a man who understands what giving back is all about. He wants people to remember Jules Rivlin. So isn’t it fitting that a man, who built a prosperous life selling light bulbs, would come up with a great idea? He endowed a $25,000 scholarship in Rivlin’s name.

To him, that lifelong friendship with “Riv” turned out to be priceless.