An autobiography about the journey of Huntington icon Red Dawson sheds new light on the former coach’s survivor’s guilt, anger and healing in the years following the Marshall plane crash.

By Carter Taylor Seaton

HQ 95 | AUTUMN 2016

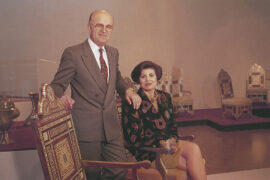

Today, the hair color that gave William “Red” Dawson his nickname has faded to a snowy white. His persona has mellowed as well. Perhaps time has done both. But one thing is for certain – the making of the movie We Are Marshall played a huge role in his transformation from troubled former Marshall assistant football coach to artist, public speaker and, most recently, book author. According to Red, the experience of writing his autobiography, A Coach in Progress, (released in November 2015) with ghostwriter Patrick Garbin, completed the catharsis.

Red Dawson was one of three Marshall football coaches who were not aboard the DC-9 chartered plane that crashed on its return flight from the East Carolina University game on Nov. 14, 1970, killing all 75 aboard including players, fans, coaches and Marshall officials. He missed the flight when he decided to drive back to Huntington and do some recruiting along the way.

“My life went to hell in a handbasket on Nov. 14, 1970,” Red says. “The period after the crash was the worst time of my life.”

When Marshall decided to rebuild the decimated football program, he returned and served as acting head coach until the university hired Jack Lengyel in the spring of 1971. Despite rumors to the contrary, Red, who was just 27 at the time, truly wanted the head coaching position. But after the disappointment of being passed over for the position, he agreed to stay on as an assistant.

Contrary to what was portrayed in the film We Are Marshall, the former Florida State University football standout spent two seasons coaching the Young Thundering Herd before resigning in 1972. Why the discrepancy? So traumatic were the times following the plane crash that for 44 years Red had no memory of that second season – it was as if it never happened. For years he swore he’d stayed only one year after the crash. It was only after doing research for his book in 2015 that he discovered the truth.

And not many people know that it was Red Dawson who was the inspiration for the We Are Marshall motion picture. The script had been written by 26-year-old Jamie Linden, a 2001 Florida State University alumnus who had read an article about Dawson and the 30th anniversary of the crash in the school newspaper. He had been obsessed with the story ever since, and turned it into a screenplay that Warner Bros. bought in March 2004.

After leaving coaching, Red went to work as a trainee for Wilson Construction, which meant he was “a shovel man and a laborer.” After a number of years, he decided to leave and start his own construction business. After a successful 35-year career in that industry, Red has semi-retired, although he’s not the type to just sit still. While he grants that he may have given up his dream of a coaching career too soon, he’s satisfied that he was successful in another field.

“I quit coaching football. I don’t regret it. The doors weren’t opening,” he recalls. “I thought maybe I could get another job somewhere and it just didn’t work out. We had to change course and we did. I’m proud of it.”

• • • •

A longtime friendship with coaching legend Bobby Bowden is one serendipitous relationship that brought Red to Huntington. Growing up in Valdosta, Georgia, the “country boy” played football well enough at Valdosta High School to be offered a full scholarship to both Florida State University (FSU) and Western Carolina.

“I chose FSU because of my fondness for FSU coach Perry Moss,” writes Red in his autobiography. But by the time Red arrived Moss had moved on to coach professionally in Canada for the Canadian Football League.

Two years later, Bobby Bowden arrived at FSU to coach the receivers and the two became good friends. He’s the man who hung the “good ol’ country boy” moniker on Red. After he graduated from FSU as an All-American as both a tight end and defensive end, the Los Angeles Rams and the Boston Patriots drafted him. He signed with the Patriots, but was cut late in his first season.

Moss then reached out to Red and invited him to come play for the Orlando Panthers, and “maybe coach a bit as a part-time assistant,” Red recalls. The following year, 1968, Moss accepted the head-coaching job at Marshall, and Red followed him. Ironically, Bowden had been offered that job but turned it down. “I was almost on the plane with the Marshall team,” Bowden has said.

• • • •

In the aftermath of the 1970 plane crash, Red suffered from what is known today as survivor’s guilt.

“If the diagnosis includes routinely having wished I had been on the plane with my friends, and experiencing nightmares that are absolutely hell – so bad that when I wake up from one I dare not go back to sleep to avoid returning to the same nightmare – for decades, then, yes, I guess I did indeed suffer from survivor’s guilt.”

Marshall assistant football coach Red Dawson, top center, speaks with mourners on Nov. 15, 1970, during a memorial service at the Veterans Memorial Field House honoring the 75 people killed in a plane crash the night before at the Huntington Tri-State Airport.

No counseling was offered, so he struggled by himself. He absented himself from Marshall football entirely. He didn’t attend games and didn’t even watch football on television. He says he was angry with everyone associated with Marshall. Although many thought that included Lengyel, Red now says, “I simply was jealous of him.”

The year after the crash, Marshall erected a memorial fountain in the center of campus to honor those who had perished. Red attended the dedication ceremony, but it was the last time he participated in the annual memorial service for 35 years. During those years, he went to campus, but didn’t appear at the ceremony, which was then held at night. Instead, he hid behind an enormous sycamore tree that afforded him a view, but kept him out of the public eye. Each year, he put a notch on the tree to mark his attendance.

“I wasn’t trying to hide from paying respect to those who perished, but rather I simply didn’t want to talk to anyone, and didn’t want anyone talking to me,” he writes in his book.

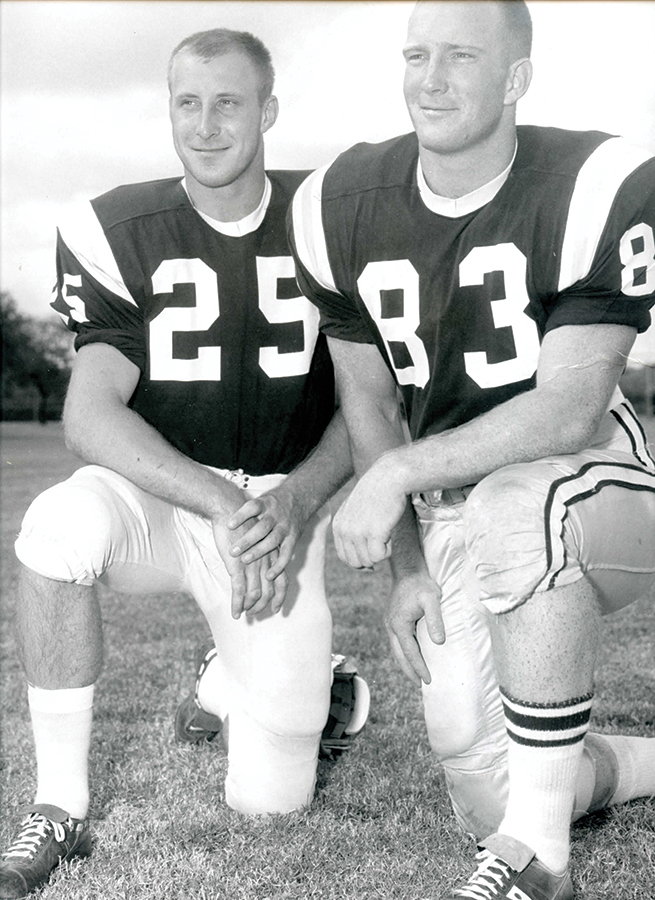

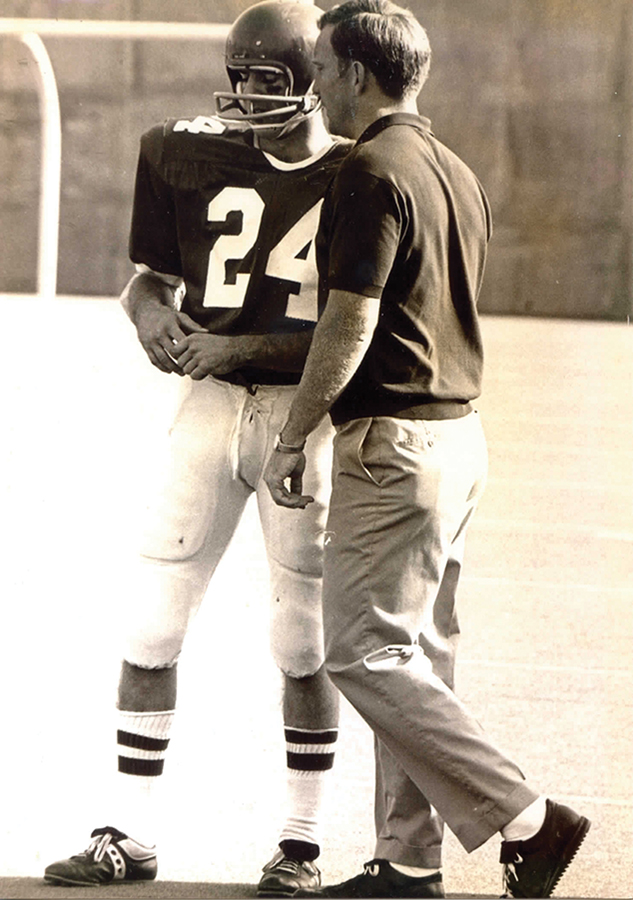

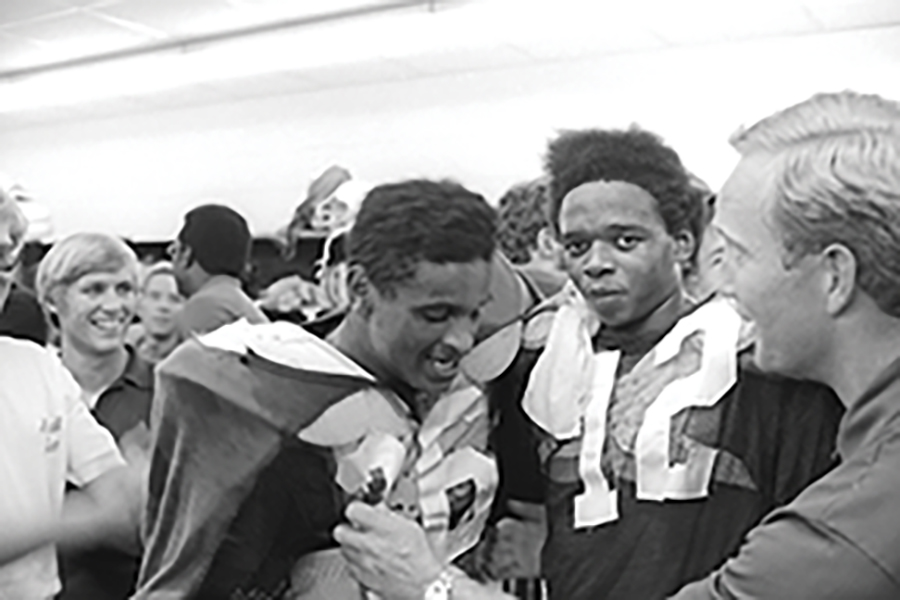

Terry Gardner, left, and Reggie Oliver celebrate after the Young Thundering Herd’s 15-13 victory over Xavier in 1971. Gardner caught a screen pass from Oliver and raced to the end zone for the winning score on the final play of the game. Coach Red Dawson is at right. The Young Thundering Herd of Marshall University (dark jerseys) beat Xavier University (white jerseys) 15-13 on Sept. 25, 1971, at Fairfield Stadium. It was the first win since the Nov. 14, 1970, plane crash that killed 75 Marshall University football players, coaches and fans upon returning to Huntington from East Carolina University, where the team had just suffered a heartbreaking 17-14 loss.

Sometime in the early 1980s, Red began to thaw a little. His friend Joe Feaganes, former Marshall golf coach, invited him to tailgate when Marshall still played at Fairfield Stadium. Red was reluctant to go, but when Feaganes told him that tailgating involved standing around, drinking beer, but not going into the stadium, Red was in. For years, that was as close as he came to an actual football game.

“I then got Red playing in Marshall’s Herd Golf Day,” Feaganes explains. “It’s a fundraiser for the golf program. It was another step closer to Marshall football.”

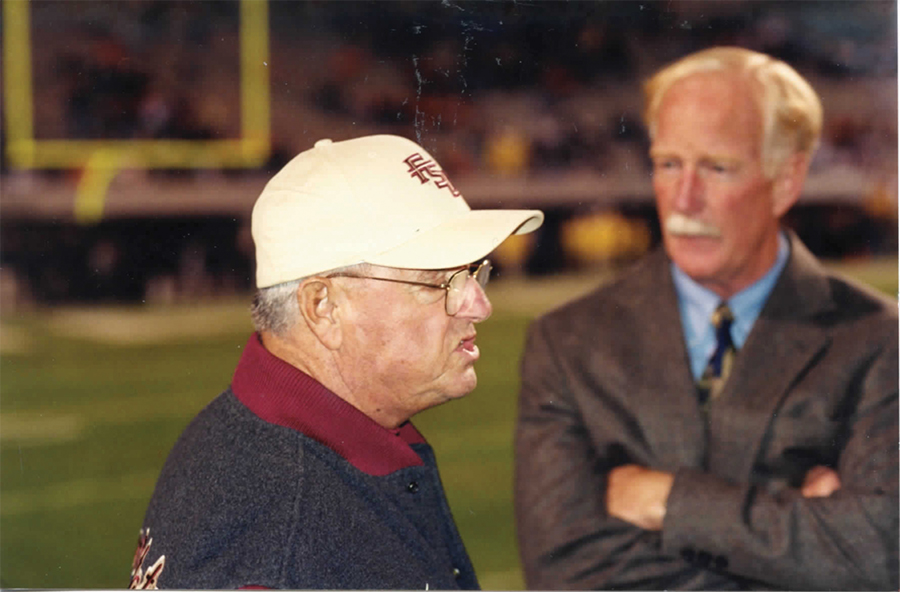

Then in the 1990s, Marshall reached out to him. Those were the days of Jim Donnan, and later Bobby Pruett. Red knew of Donnan before he became Marshall’s head coach in 1990. Donnan also had known Red’s brother Rhett when he played at FSU. Nevertheless, when Donnan invited Red to join him for coffee or attend an event, he either turned down the new coach outright or had some excuse as to why he couldn’t come. When Bobby Pruett stepped in as head coach in 1996, the welcome mat stayed out. According to Red, “Bobby was difficult to say no to when he asked me to associate with the team.” Both coaches had made him feel welcome and comfortable around the program again.

In 1997 when Marshall opened its season on the road against West Virginia University, Red was there. “I was Coach Pruett’s guest on the sidelines as an honorary coach. What an honor! Never did I think I would be yelling along the Marshall sidelines again,” he says. Later, Marshall even assigned him a prime tailgating spot near the 50-yard line on the West Lot of the Joan C. Edwards Stadium.

As Marshall’s football successes mounted, folks began talking about a movie about the program’s rise from the tragedy. Red got several of those calls, and politely turned them down when they asked for his help. But, in 2006, when Hollywood came to town, Red agreed to be a consultant for the Warner Bros.’ movie, We Are Marshall.

“Although I was convinced that consulting on the movie would conjure up old nightmares, which by then had become only an occasional occurrence, I felt I needed to do it for the sake of those who perished in the tragedy – to honor them.”

While many feared Hollywood would not treat the story of the tragedy with the proper respect, the director Joseph McGinty Nichol, McG as he is called, said he always planned to do just that.

“My goal was just to tell an honest story that was an accurate reflection of the emotion of the time, and how that story can inspire us all,” he said. When the two met, Red knew McG’s vision would allay everyone’s concerns.

Red was soon immersed in the movie’s production. Matthew Fox, who played Red in the film, invited him to fly out to Hawaii where Fox was on location, in order to get to know him. The two had much in common and became good friends. McG also cast Red in a role in the movie. He says his directions were to “just look serious.” McG, however, says Red did more than that.

“In Hollywood we have a saying: ‘Lit from within.’ Red has that special quality of being lit from within. When the camera goes on him, he just goes for it.”

Former Marshall University assistant coach Red Dawson speaks Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2006, during Marshall University’s 36th memorial service for the 75 people who died in the 1970 plane crash. Dawson, who contributed to the rebuilding of Marshall’s football team, spoke at the ceremony for the first time in its 36-year history.

Part of Red’s consulting contract also required him to do some public relations work. While he worried the nightmares would return if he talked about the tragedy, surprisingly, they didn’t. Instead, there were fewer. The more he talked about it, the more manageable the survivor’s guilt became.

In 2006, with the movie about to be released, Red agreed to give the memorial fountain ceremony’s keynote address. Despite having difficulty getting through it and embarrassed at showing his emotions, Red says, “The experience wasn’t bad at all.” Now, at the ceremony each November, he is in attendance.

Red says the movie also led him to write his book, A Coach in Progress, released in November 2015. He met his co-writer, Garbin, through longtime friend, Rosie Alexander, who lives in Athens, Georgia. Garbin knew of Red and asked if he’d tell his story to him. Red agreed, and now admits doing so was tremendously cathartic. “I never had another nightmare because of it,” he says.

While Red and the tragedy will be inextricably linked forever, there’s another Red Dawson that only his close friends know. As a young boy, he loved to draw, mostly birds, he says. Now he paints using acrylics and oils. He could make a whole new career as an artist if he chose. He’s got a good eye for the art of others, as well. After meeting sculptor Stan Mullins in Athens, Red worked with Marshall’s Athletic Director Mike Hamrick on a project that culminated in the 2015 placing of Mullins’ three bison at the Chris Cline Athletic Complex on Third Avenue. A small replica of one of the bison also stands in Red’s front yard.

He’s also a pretty fair singer. For years, he and his friend Fred Sammons entertained at parties of friends. Called the “Fred & Red Show,” the duo sang old country music with Fred on guitar and Red harmonizing.

And he’s a deeply religious man.

“After the crash, I was mad at God,” he admits. “In time, I got my mind right and determined that ‘The Old Master,’ as I call Him, doesn’t interfere with things that cause a tragedy.”

Perhaps it’s his spirituality that caused him to befriend Patrick Kelty, a senior at Marshall who is on the autism disorder spectrum. Kelty knew who Red was from watching We Are Marshall and he wanted to meet him. After introducing himself one day at Marshall’s Harless Dining Hall, where Red often ate with his friends, the two became buddies. Now Patrick, who is also one of the flower bearers at the fountain ceremony each year, tailgates with Red.

No longer troubled or angry, Red says he wants his legacy to be broader than just the story of the tragedy.

“I hope folks will one day say that I was a good ol’ boy that everybody liked,” Red says.

If recent comments are any indication, he’ll have his wish.

McG says, “I have so much respect for the man. He’s the sort of individual that I really admire. He is a man of character and depth. He certainly touched my life forever.”

In Red’s book, Bobby Bowden said in his foreword, “Red is as good an example of a ‘good ol’ southern country boy’ as any I know.”

And finally, Patrick Kelty says, “He’s a good guy, one that many people would want to get to know.”