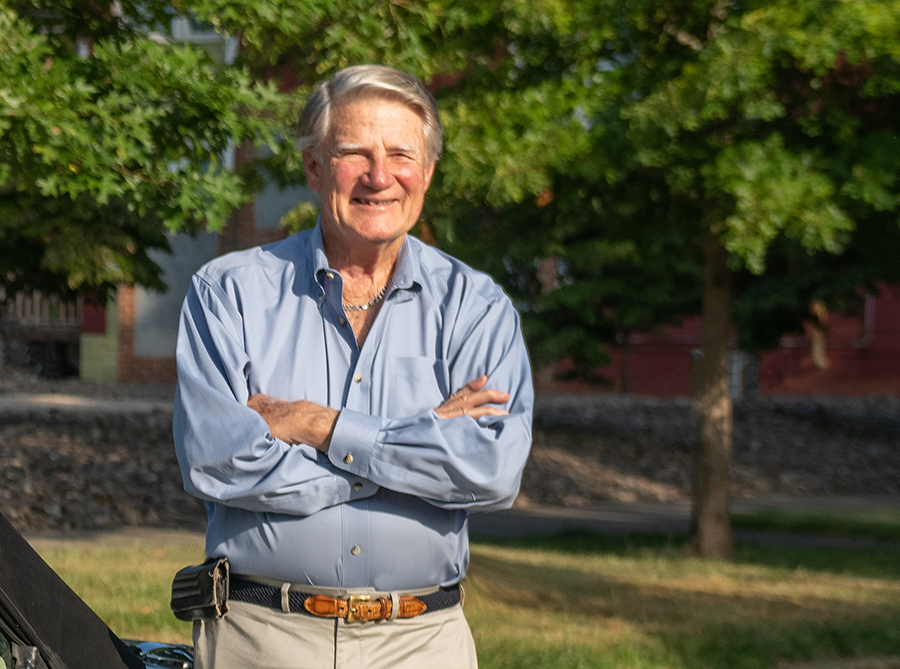

He may be modest and fly under the radar, but this Huntington businessman can be counted among the city’s greatest philanthropists and civil leaders.

By Carter Seaton

HQ 109 | SPRING 2020

Don’t let Sterling Hall’s quiet humor and modesty fool you. Behind that disarming smile is a canny businessman who began his career as a teenager and now, in retirement, spends much of his time broadly distributing the rewards of his success.

Born in Huntington to a well-known entrepreneurial family — his great-grandfather James A. Diddle founded Huntington Boiler Works (which would later become Huntington Steel) in 1904, and his grandfather Sterling Diddle founded Guaranty Bank in 1939 — Hall entered the family business early. At 16, he convinced the school board to let him work in the steel plant, where he not only learned the business from the ground up, but got to know the workers as well.

“The greatest asset we have at Huntington Steel or at any business is the people who work with you,” he explained. “A good businessman knows that.”

Hall attended Miller Elementary and Cammack Junior High until some teenage mischief prompted his father, Bob, to send him to Kentucky Military School for the next four years. After high school he enrolled at Duke University but a year later chose to return to Huntington and finish his degree in business at Marshall College.

“I felt it was important to return to the city and get to know not only the community, but the people I would be working with,” he said.

While at Marshall, Hall lived with his maternal grandparents. His grandfather and namesake, Sterling Diddle, soon became the guiding influence in his life. To say that Sterling admired his grandfather would be a vast understatement.

“I was very fortunate to have learned so much from him about business, banking and how important decisions are made,” Hall explained. “But even more importantly, he taught me about life and what it means to be a gentleman.”

After graduating from Marshall, Hall went to work full time at Huntington Steel. At the time, his father Robert and uncle John Adrian were running the plant, and the company’s primary focus was steel production and warehousing steel. But when Hall got involved in the business, he changed its direction to include the fabrication of steel beams and columns.

“Sterling Hall liked to be on the cutting edge,” said Roy Maynor, a former manager at Huntington Steel. “If there was a piece of equipment that made our work easier and faster, he did not hesitate about purchasing it to give us an advantage over our competition.”

Hall said he learned an important lesson about investing for the future from his shrewd grandfather.

“I remember this time when I was considering purchasing a used burning machine for work we didn’t even do at the time,” said Hall. “I asked my grandfather his advice, and he told me, ‘You buy a piece of equipment and then you will find work for it.’ He was right — because I bought it, and it wasn’t long before we were running it two shifts a day at the plant. My grandfather was a very smart man.”

Today, many local building projects bear the Huntington Steel stamp, including Marshall’s Arthur Weisberg Family Applied Engineering Complex and the Stephen J. Kopp Hall for the School of Pharmacy. While the plant is located at 100 Third Avenue in Huntington, Hall also opened branches in Chesapeake, Ohio, Morgantown, WestVirginia, and Pikeville, Kentucky, as well as a warehouse in Logan, West Virginia. He later took on a business partner and opened a steel fabrication plant in Charleston, West Virginia.

Although he retired in 1994, the company is still family-owned. His son-in-law, Mike Emerson, is the current CEO, and Hall’s two grandsons, Alex and Dan, have been learning the business their entire lives and hope to continue the family tradition.

Looking back, Hall’s employees said he was greatly respected.

“He was the best boss I ever had,” said Maynor. “When he hired me, he told me the job description and what he expected of me. He did not micromanage. It seemed like he was a coworker. You would never know he was the owner of the company.”

Phil Eaton, a former fabrication division manager at Huntington Steel, agreed.

“He was a fair boss who treated his employees like he expected to be treated, and that included sharing the profits with them,” Eaton said. “I also admired the balance in his life. He was not an ‘all work, no play’ kind of guy. He was a pilot, world traveler, snow skier and avid boater who, at one time, lived on a boat on the Ohio River.”

The steel business wasn’t the only place Hall followed in the footsteps of his grandfather. Sterling Diddle was the president and chairman of the board of the Guaranty National Bank and he put his grandson on the board right out of college.

“I gathered a wealth of knowledge just sitting in that board room while keeping my ears open and my mouth shut and listening to my grandfather and older gentlemen on the board.”

He must have learned a great deal; because when his grandfather’s health began to fail, Hall became co-chairman of the board. Following his grandfather’s death, Hall took his place as chairman.

“His passing was a tragedy in my life, but I feel he prepared me well for my future,” Hall said.

Years later, Hall oversaw the merger of Guaranty with the Charleston-based National Bank of Commerce, and eventually the banks became a part of Huntington Bankshares headquartered in Columbus, Ohio.

Banking didn’t leave him, however. In 1998, he and several other Huntington business leaders launched a new Guaranty Bank and Trust. A decade later the bank merged with First Sentry Bank, now part of Wesbanco headquartered in Wheeling, West Virginia. By then, Hall was ready to retire and today divides his time between his homes in Huntington and Beaufort, South Carolina.

But retirement hasn’t slowed his involvement in or passion for the Huntington region. He may not be a regular at Rotary meetings these days, but dozens of nonprofit organizations still feel his presence. One of the most visible signs of his philanthropy is the fountain at Ritter Park’s entrance. In 1999, Hall and several other family members donated the funds to build the fountain, which they dedicated to Sterling Diddle. Twenty years later, Hall helped the park board fund the total renovation of that fountain, adding computer programming to control its jet sprays and LED lighting.

According to realtor Francis McGuire, who has been Hall’s friend for over 35 years, the city will long benefit from the more than 250 trees he has purchased and planted around town. Every year he has each tree fertilized and mulched.

Following the 2012 shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, that took the lives of 26 people, including 20 children, Hall contacted the park board with an idea. He wanted to build a park on the site of the former Miller Elementary School in remembrance of the Sandy Hook victims. There, he planted 26 trees — one tree for each victim — and erected a stone structure that lists the names of those who contributed to the formation of the park.

When Hall learned about a local African-American cemetery that had been neglected for years, he joined other volunteers, rolled up his sleeves and started clearing brush himself. Realizing it was a task that required more than a few dedicated volunteers, he began seeking assistance from various civic groups.

With the help of Huntington City Council member Carol Polan and numerous volunteers, work continues on Bethel Memorial Park Cemetery. Today, more than 800 graves that were overrun by brush and trees are gradually being reclaimed and listed in a comprehensive grave registry organized by the Westmoreland chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution.

Through the years, Hall has served on many nonprofit boards. He and Phil Cline spearheaded the campaign to build the modern addition to the Huntington YMCA. He has been a supporter of the Huntington Cabell Wayne Animal Shelter and Little Victories Animal Rescue, a no-kill shelter in Ona, West Virginia. Whether it has been buying sports uniforms for underprivileged youth or sponsoring exhibits at the Huntington Museum of Art, Hall continues to give back each and every year. The list of charities that benefit from his generosity is simply too long to list. Hall said he feels a need to give back to the community that has allowed him to grow and prosper.

“I take my IRA funds each year and give it all away,” he said matter-of-factly. “I typically give to 15 different charities.”

Sterling Hall loves his hometown and it shows. Despite suggestions that he be put on the Huntington Wall of Fame, he has always demurred. And while most civic leaders say that he certainly deserves it, he doesn’t agree. He’s modest that way, remember?