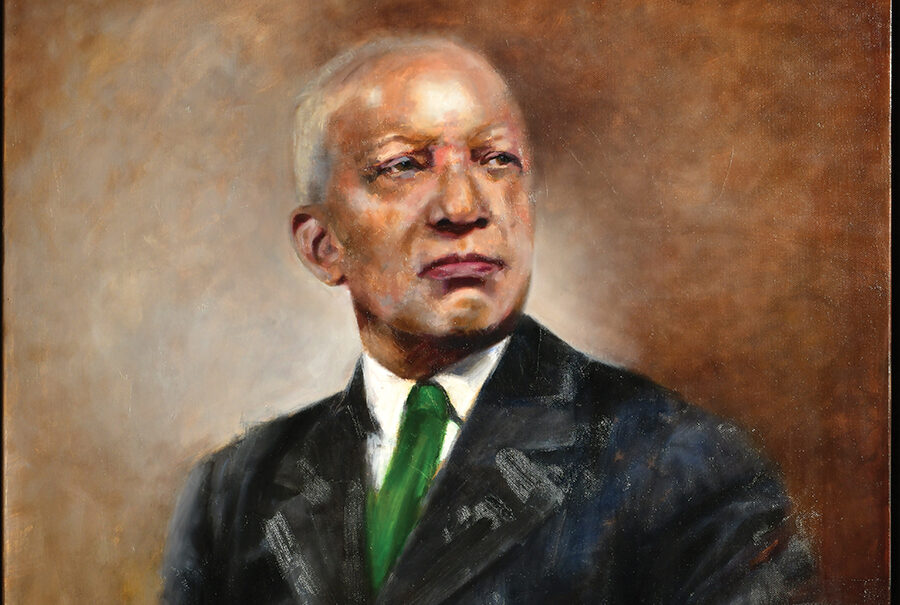

Huntington’s own Carter G. Woodson founded Black History Month and is acknowledged as the Father of Black History. This is his inspiring story.

By Sara Leuchter Wilkins

HQ 112 | WINTER 2021

The city of Huntington, West Virginia, was barely two decades old when the young Black man who was to become one of its most accomplished citizens first laid eyes on his new home. He had ventured in from the coal fields of Fayette County to join his family, who moved to Huntington from rural western Virginia, lured by the promise of economic opportunity and rumors of a school for Black students.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson, now universally acknowledged as the “Father of Black History,” rose from humble beginnings on a rural farm in Virginia to international prominence as a noted educator, author, editor and scholar. He authored more than 12 books on the history of Blacks in the United States including The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, The Mis-Education of the Negro and The Negro in Our History.

In addition, Woodson founded the Black history movement in 1915 when he created the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), followed by his founding The Journal of Negro History and The Negro History Bulletin.

In addition, Woodson founded the Black history movement in 1915 when he created the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), followed by his founding The Journal of Negro History and The Negro History Bulletin.

In 1926, Woodson began the process necessary to publicly recognize the contributions of Black Americans to U.S. and world history. He selected February as the time for an annual celebration because it was the month both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass were born. What Woodson began as “Negro History Week” is now celebrated as “Black History Month.”

Subsequently, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) awarded Woodson the Spingarn Medal, then considered the highest award an African American could receive. Since his death, more than 30 schools, libraries and parks across America have been named in his honor. Today, Woodson’s papers are housed in Washington, D.C.’s Library of Congress and his home in that city has been designated a national historic site.

. . . .

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on Dec. 19, 1875, in New Canton, Virginia, surrounded by poverty. His parents, both former slaves, were married in 1867 and had nine children. Woodson worked the family’s six-acre farm and never forgot the harshness of his childhood. Sometimes, when hungry, he ate the persimmons in the woods. Other times, he said, he ate “the sour grass that grew early in spring out of the providence of God.”

From early childhood, Woodson was enthralled by tales of relatives and their first-hand accounts of slavery and the Civil War. These stories and many others whetted Woodson’s appetite to learn more about the past.

Woodson’s family remained in Virginia through the early 1870s. Within a few years, however, they learned of a new city on the Ohio River called Huntington, in the state of West Virginia, where wages were said to be generous. The young couple packed their belongings and joined a group trekking through the mountains to the Ohio River.

Meanwhile, Woodson and his brother Robert had taken jobs working in the coal mines in Nuttallberg, West Virginia. It was during this period that Woodson encountered numerous illiterate Black coal miners which greatly troubled him. He would later state that his years in West Virginia marked a turning point in his career.

In the fall of 1895, Woodson left the mines and moved to Huntington. The city must have seemed a booming metropolis, with more than 10,000 citizens, new buildings, paved roads and street lights on nearly every corner. Most importantly for Woodson, the city was home to Douglass School, a six-room building for Black students located on the corner of Eighth Avenue and 16th Street. (It would later be renamed Douglass High School and move to 10th Avenue and Bruce Street.)

Woodson, just months shy of his 20th birthday, entered Douglass without much formal education and graduated in one year. He furthered his studies at Berea College in Kentucky before accepting a teaching position in the small town of Winona in Fayette County, West Virginia.

In 1900, Woodson triumphantly returned to Huntington to assume the duties of teacher and principal at Douglass. When his sister Bessie graduated from Douglass in 1901, Woodson proudly signed her diploma. In 1903, he accepted a teaching job in the Philippines, where he would note Filipinos being insufficiently taught much like Black students were being miseducated in America. He would later utilize these observations to develop his Black history program.

In 1907, he returned to the United States intent on furthering his education. He earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Chicago. Then Woodson enrolled at Harvard University and pursued a doctorate in history, which he earned in 1912, becoming only the second Black man in the school’s history to receive such an honor — the first was W.E.B. DuBois.

Woodson finally had the credentials to start pursuing his cause — returning Blacks to American and world histories and improving race relations. He eventually settled in Washington, D.C., intent on dispelling the prevailing thought that Blacks had no history worth appreciating.

“When I arrived in Washington, D.C., and began my research, the people there laughed at me, especially my ‘hayseed’ clothes,” Woodson wrote. “When I, in my poverty, had the ‘audacity’ to write a book on the Negro, the ‘scholarly’ people of Washington laughed at it.”

After founding the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, he authored at least a dozen books between 1915 and 1950. Woodson became a powerful force in Black culture, known for his scientific approach to documenting history. He believed Black History should be studied throughout the year and used his idea for Negro History Week as a starting point. The cornerstone for the millions of people who celebrate Black History Month in February every year is the book The Mis-Education of the Negro, first published in 1933. Woodson’s ideas continue to be espoused through sales of the book. Always in vogue, it remains on many bestseller lists; and many regard it as a manifesto.

In 1976, Gerald Ford became the first U.S. president to recognize Black History Month. In 2016, President Barack Obama made his last proclamation in honor of Woodson’s pioneering initiative, now recognized as one of America’s oldest organized celebrations of history.

Many visitors to Huntington are often surprised to learn of Woodson’s footprints. Dr. Kevin Yingling, a professor in the Marshall University School of Medicine and former dean of the School of Pharmacy, recalled with astonishment the time a friend (a professor of history at the University of South Carolina) was visiting Huntington and spotted the statue of Woodson on Hal Greer Boulevard. “I was driving down the street with my friend and his children when he suddenly yelled, ‘Stop the car!’ He told his children, ‘That’s Carter G. Woodson! Do you know who Carter G. Woodson is?’” Yingling explained. “I parked the car and then looked on as my friend stood beneath the statue extolling who Carter G. Woodson was and all the things he had accomplished. He was so excited that he saw the statue and that his kids got that little piece of history.”

Many visitors to Huntington are often surprised to learn of Woodson’s footprints. Dr. Kevin Yingling, a professor in the Marshall University School of Medicine and former dean of the School of Pharmacy, recalled with astonishment the time a friend (a professor of history at the University of South Carolina) was visiting Huntington and spotted the statue of Woodson on Hal Greer Boulevard. “I was driving down the street with my friend and his children when he suddenly yelled, ‘Stop the car!’ He told his children, ‘That’s Carter G. Woodson! Do you know who Carter G. Woodson is?’” Yingling explained. “I parked the car and then looked on as my friend stood beneath the statue extolling who Carter G. Woodson was and all the things he had accomplished. He was so excited that he saw the statue and that his kids got that little piece of history.”

If visitors are surprised the Father of Black History’s early years go through Huntington, it is also a surprise to many residents. Community knowledge of Woodson’s accomplishments have been long dormant. The U.S. Postal Service issued a postage stamp honoring Woodson in 1984, generating local interest in Woodson and prompting creation of a committee raising awareness, decades following his death. The committee transitioned into the Carter G. Woodson Memorial Foundation and raised funds for the erection of the statue, which was dedicated on Sept. 29, 1995, near the site of the original Douglass School.

Even though Woodson was inducted into the Greater Huntington Wall of Fame in 1991, Huntington Mayor Steve Williams admits the city is still playing catch-up; he has been leading the charge, declaring, “Carter G. Woodson changed the world.” Williams proposes using Woodson’s story to inform the world about Huntington’s connections to Black History Month.

In his later years, Woodson continued to write, lecture and edit. He lived to see a Black man become a full professor at Harvard University and a Black student graduate from the United States Naval Academy.

Woodson died April 3, 1950, at his home in Washington, D.C., at the age of 74. He left his Washington and Huntington homes and just about everything else he owned to his cause, the face of which was the association. He left behind a great legacy not just for Blacks, but for all Americans. His indefatigable spirit and thirst for knowledge has enriched the lives of generations, and will continue to do so for untold generations to come.