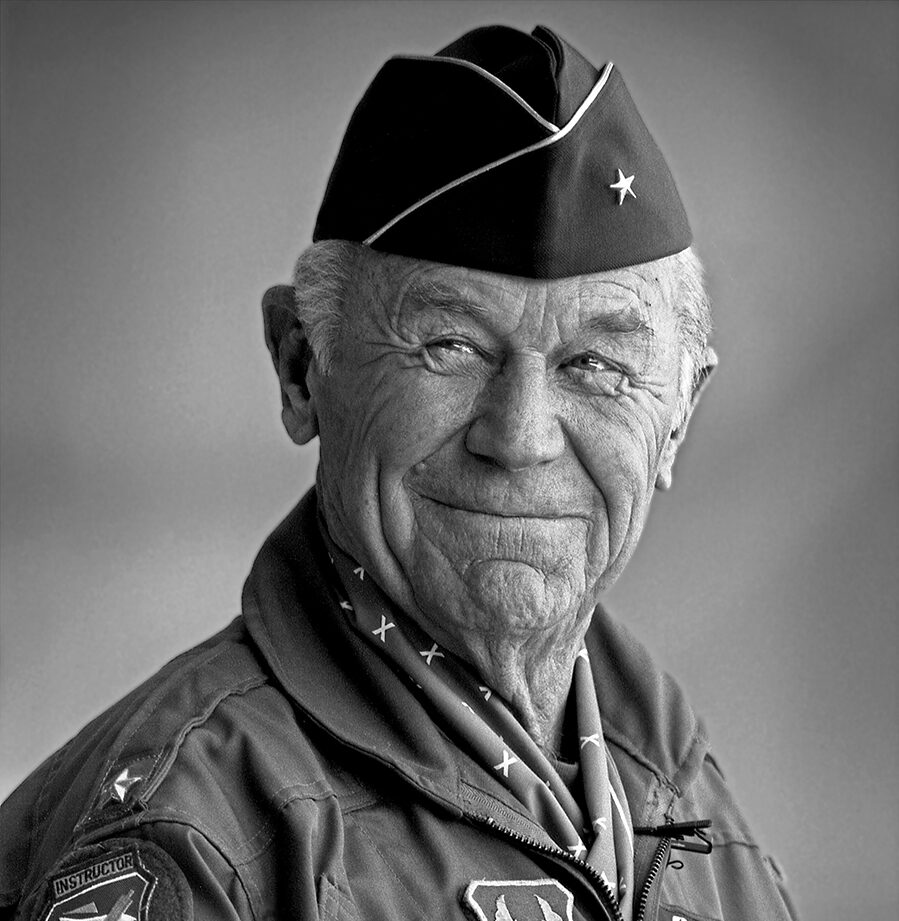

He did more than smash that brick wall in the sky. Chuck Yeager lived life to the fullest and along the way became the greatest pilot in history.

By Jack Houvouras

HQ 112 | WINTER 2021

A pair of tattered, torn, mud-stained boots charged through the dense backwoods of Hamlin, West Virginia. The morning fog hadn’t even considered rising at this early hour; but that didn’t deter a young schoolboy, just 8 years old, from weaving his way through hills and streams, his rifle in hand, en route to a small patch of hickory trees where he knew squirrels would be feeding. He knew because of the wisdom passed down by his father, and because of his own fascination with the outdoors — his playground — where he was a student of all that nature afforded. The youngster slowed; and his short, thin frame emerged from the fog clad in dungarees, a ragged red flannel shirt and a ball cap. His tan brow furrowed, he raised his rifle as his steel-blue eyes homed in on a small target some 75 yards away. A crackling shot rang out, and suddenly a small, headless gray object fell from the trees.

Little Charles Yeager smiled, knowing that none of his friends could have pulled off that shot and, more importantly, knowing that tonight’s dinner would offer more than just cornbread and buttermilk. By now the school bell was ringing as Yeager headed home. He knew he was in for an ass-chewing from the principal, but he didn’t care. This was where he truly longed to be — exploring the mysteries of nature, at one with his knowledge and skill, proving to himself that he was good at something, possibly even the best. He was proud of his feat, confident in his ability and alive with the awareness that he was, in the truest sense, rich.

Chuck Yeager didn’t grow up rich, at least monetarily, in Hamlin. The small town was a proud, hardworking community so deep in the “hollers” of Appalachia that, as the old saying goes, you had to “pump in sunshine.” But it was here that Yeager spent his youth, quite contentedly, in poverty. His father worked as a driller in the gas fields of West Virginia while his mother took care of the home and their five children. Despite spending six days a week on the road working, Yeager’s father always found time on Sundays to teach his children to fish, hunt and survive, often with style, in the harshest of environments. Early on, young Charles, as he was called by the townsfolk, took an interest in his dad’s work, absorbing every piece of knowledge he could about the machines his dad operated. He also shared his father’s love of cars and studied every detail of the old man’s Chevy truck. It was this upbringing in the charming yet rural setting of Hamlin that laid the groundwork for the future success of the greatest pilot who ever lived.

Following a lackluster trek through high school, Yeager enlisted as an airplane mechanic with the United States Air Force in the midst of World War II. He hoped his new path would take him to faraway places that might hold the same magic as the West Virginia woods behind his home. He helped service planes before a newly formed “Flying Sergeants” program gave him the opportunity to attend flight training. Believe it or not, his first few flights were inauspicious, finding the typically resilient Yeager puking his brains out. But he quickly overcame his airsickness and began to set himself apart as the best flier in the class. He possessed an innate competitiveness that drove him to excel, to be the best at every endeavor he undertook. It wasn’t long before he was buzzing trees, flying just atop the deck and performing slow rolls in the open skies over Nevada. He had found a new place to explore — and its boundaries were nearly endless.

“You’re whipping through a desert canyon at three hundred miles an hour, your belly just barely scraping the rocks and sagebrush, your hand on the throttle of a P-39 fighter,” he wrote in his No. 1 bestselling autobiography, Yeager. “It’s a crystal-clear morning on the desert … and the joy of flying makes you so damned happy that you want to shout for joy. You feel so lucky, so blessed to be a fighter pilot.”

Yeager flew incessantly throughout training, getting his hands on every airplane on base. When he wasn’t flying, he was studying every aspect of each plane, down to the last nut and bolt. And when he wasn’t near planes, he was either waxing poetic about them at the local watering hole or dreaming about them in his bunk.

During a military flight back east, he decided to visit Hamlin. He followed the Ohio River into Huntington, then banked south for his hometown. At approximately 7 a.m., he hit full throttle and dove on Main Street at 500 mph before pulling up, doing some slow rolls and buzzing the treetops. The townsfolk weren’t amused. An elderly lady was so frightened that she had to be taken to the hospital, and a farmer was left fuming because his entire crop of corn had been blown down.

Yeager’s training then took him to California. While there, he and a buddy stopped into a local gymnasium to arrange a USO dance. Inside a small office he found a “very pretty brunette” seated behind the desk. Glennis Dickhouse, an 18-year-old high school graduate from Oroville, California, who some said resembled actress Vivien Leigh, looked annoyed when the brash, young fighter pilot asked her to arrange a dance that evening for 30 men.

“You expect me to whip up a dance and find 30 girls on three hours’ notice?” Glennis exclaimed. Yeager fired back, “No, you’ll only need to come up with 29, because I want to take you.”

There was instant chemistry between the two, even though Glennis found Yeager’s West Virginia accent unfathomable.

“I barely understood every third word he spoke,” she wrote in Yeager. “But … I sensed that he was a very strong and determined person, a poor boy who had started with nothing and would show the world what he was really made of. That was the kind of man that I hoped one day

to marry.”

After a whirlwind romance, Yeager received his orders to report overseas. He corresponded with Glennis frequently and began enclosing his paychecks. “Here,” he would write, “bank this for us.”

Yeager arrived in England with the 363rd Fighter Squadron and began flying his P-51 Mustang, which he named Glamorous Glen, over the dangerous skies of France and Germany. But, after only eight missions and the day after scoring his first kill, the 21-year-old was shot down over German-occupied France. He was flying at the tail end of a group of P-51 Mustangs that were escorting B-24s on a bombing run. As the “tail-end Charlie,” he was in a very vulnerable position. German fighters typically attacked from above and behind, and it was the tail-end Charlie that got hammered first. As his plane plummeted to the ground, Yeager punched out.

Wounded with a gash on his forehead and a hole in his leg caused by shrapnel fragments, Yeager was alone and on the run. He called upon all the knowledge and skills that he had acquired in the rugged hills of West Virginia to survive. After hiding out for several days in a farmer’s barn, he slowly climbed his way over the snow-covered French Pyrenees, narrowly avoiding death from the elements on one occasion and gunfire from a German patrol on another, before finally making his way into Spain where freedom awaited.

What also awaited Yeager was a trip back home. A “no more combat” rule for evaders was being enforced to protect the French underground. If Yeager were shot down again, he might be tortured into divulging escape routes.

But Yeager would have nothing to do with rules. “I was raised to finish what I started, not slink off after flying only eight missions,” he wrote in Yeager. “Screw the regulations. I was brassy and pushed my way up the chain of command at group headquarters arguing my case.”

In the first of a long line of bold feats, Yeager was granted a meeting with Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. “General,” he said, “I don’t want to leave my buddies after only eight missions. It just isn’t right. I have a lot of fighting left to do.”

Eisenhower ultimately granted his request, and the war was back on. Yeager attacked each day with renewed passion and verve. When an intelligence officer would warn of heavy flak and possible vicious fighter opposition on a given day, Yeager would think to himself, “I hope

he’s right.”

By now Yeager was flying Glamorous Glen II in search of German fighters and more kills. On Oct. 12, 1944, he found both. While escorting a box of B-24s over Holland, he noticed specks 50 miles ahead; his exceptional 20/10 vision would serve him well on this particular day. Yeager charged to the lead and closed in on a group of German Me-109s.

“I came in behind their tail-end Charlie and was about to begin hammering him, when he suddenly broke left and ran into his wingman,” he wrote in Yeager. “I blew up a 109 from six hundred yards — my third victory — when I turned around and saw another angling in behind me. Man, I pulled back on my throttle so damned hard I nearly stalled, rolled up and over, came in behind and under him, kicking right rudder and simultaneously firing. I was underneath the guy, less than fifty feet, and I opened up that 109 as if it were a can of Spam. That made four. A moment later, I waxed a guy’s fanny in a steep dive.”

Yeager had just scored five victories, making him one of the few fighter pilots in history to become an “ace in a day.” The front-page headline in Stars and Stripes declared: FIVE KILLS VINDICATE IKE’S DECISION. The Yeager legend had begun.

“He flew like a demon and was always taking calculated risks that are the essence of his personality,” noted his close friend and squadron leader Bud Anderson in Yeager. “We all like to buzz, but Chuck buzzed a few feet lower than the rest of us. And when Yeager attacked, he was ferocious. Yeager was the best. Period. No one matched his skill or courage or, I might add, his capacity to raise hell and have fun.”

Throughout his career, Yeager attributed much of his success to luck. During one of his missions in World War II, he stumbled upon three German jet fighters. “I could barely believe my good luck,” he wrote in his autobiography. But instead of fearing their 150-mph speed advantage over his Mustang, he dove after them and became one of the first pilots to down a German jet.

Another example of his unique attitude toward combat took place in the skies over East Germany and Poland. His squadron was mistaken for a group of unescorted bombers, and the Germans scrambled every plane on the ground for an attack.

“God Almighty!” squadron leader Bud Anderson exclaimed. “There must be 150 of them.”

Yeager’s reaction? “We couldn’t believe our luck. We plowed right into the rear of this enormous gaggle of German fighters. There were 16 of us and over 200 of them, but then more Mustangs from our group caught up and joined in. Christ, there were airplanes going every which way. A dogfight runs by its own clock, and I have no idea how long I was spinning and looping in the sky. I wound up 2,000 feet from the deck with four kills. … [T]he ground was littered with burning wreckage. It was an awesome sight. That day was a fighter pilot’s dream. In the midst of a wild sky, I knew that dogfighting was what I was born to do.”

As hard as Yeager and his buddies flew, they partied with even greater zeal. They drank until either a fight broke out or someone passed out. The topic of choice most evenings was, what else, flying: “You fought wide open, full-throttle. You were a confident hunter and your trigger finger never shook. When the enemy’s plane blew up, it was a pleasing, beautiful sight. There was no joy in killing someone, but there was real satisfaction when you outflew a guy and destroyed his machine. The excitement of those dogfights never diminished. For me, combat remains the ultimate flying experience,” he explained in Yeager.

His tour of duty in World War II came to an end in 1945, and Yeager returned to the States unsure of his future. He knew he wanted to marry Glennis; beyond that, he was at a loss. In typical Yeager fashion, he showed up at Glennis’s door just after landing in California and announced, “Pack your bags. I’m taking you home to meet my folks.”

“What for?” Glennis asked.

“What do you think?” he responded.

The two arrived in Hamlin to a warm reception by the family and town. Glennis then drove to Huntington with Yeager, his mother and his sister, where they bought rings and a wedding dress. They were married at home in the family parlor and honeymooned that evening in Huntington.

As newlyweds, Glennis lived with the Yeagers in Hamlin while Chuck was assigned to Wright-Patterson Field in Dayton, Ohio, so he could fly home on weekends. His decision to stay as close as possible to his new wife turned out to be a true stroke of luck. From 1945 to 1946, Wright-Patterson was the place to be for a tenacious fighter pilot. The hangars on base were overflowing with planes, and Yeager flew every one of them. What’s more, prop planes were being phased out and a new era of jet fighters was emerging. Yeager, who was accepted as a test pilot despite his lack of education, was licking his chops. He flew eight hours a day and never missed an opportunity to take on another hotshot test pilot in a dogfight.

“I went through the entire stable of test pilots and waxed every fanny,” he wrote.

When he wasn’t flying at Wright, Yeager was performing around the country in air shows, further honing his skills. But fate would soon move him to the next great flying locale — the drab California desert, home of Muroc.

By the spring of 1947, Chuck Yeager’s name appeared on a short list of test pilots under consideration for the highly secretive X-1 project. The X-1 was a Bell aircraft shaped like a bullet with razor-thin wings and four powerful rocket chambers. Because of its eerie design and bold color, it was dubbed the “Orange Beast.” Despite lacking a college degree, Yeager was selected as the pilot to steer the experimental aircraft past Mach 1 and the elusive sound barrier.

“We had several other outstanding pilots to choose from,” noted project head Gen. Albert G. Boyd in Yeager. “But none of them could quite match his skill in a cockpit or his coolness under pressure.”

In the quiet desert, Yeager was working with an impressive team of scientists and engineers from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the predecessor to NASA. The single most important member of the X-1 team was Yeager’s flight engineer, Jack Ridley. Ridley was an excellent pilot in his own right, a standout graduate of Caltech and the only man to ever whip Yeager in a dogfight.

“Without Jack Ridley,” Yeager wrote, “the X-1 probably would never have succeeded.”

Yeager’s first few rides in the X-1 saw him push the plane from .8 to .9 Mach; but when he neared the sound barrier, the aircraft began buffeting and its controls froze. Scientists from around the world had warned that the sound barrier was a brick wall in the sky which could not be penetrated. They predicted the aircraft would shake violently and ultimately disintegrate. With Yeager’s latest flight, it appeared they were right.

But Ridley was undeterred. He sat at a desk and scratched down obscure equations. His calculations yielded a possible solution: a flying tail. It was a long shot, but Yeager and Ridley were confident the modification would work.

The evening before Yeager tested the adjustment made to the X-1, he went horseback riding in the desert with Glennis. They decided to race back to the stables, and Yeager was in the lead. Despite his exceptional vision, he never saw the closed gate in the darkness and was thrown from his horse, cracking two ribs.

Nonetheless, he reported to the hangar the next day, his ribs taped, sure that he could fly the X-1 but unsure if he could lock its heavy cockpit door. He confessed his problem to Ridley, who grabbed a broomstick, sawed off about a 10-inch piece and handed it to Yeager to use as a lever to lock the door with his good side. The date was Oct. 14, 1947.

Yeager climbed into the X-1 and was dropped from the belly of a B-29 bomber. He fired all four rocket chambers and was slammed to the back of his seat. The aircraft climbed to 42,000 feet, and his speed indicated .94 Mach. He had passed through the heavy buffeting and was still flying smoothly, like a bat out of hell. The speed indicator began to fluctuate at .965 Mach and suddenly jumped off the scale. A thunderous boom was heard on the desert floor below, and many of the brethren assumed Yeager had finally “bought the farm.” Instead, they had heard the first sonic boom in history as Yeager smashed through the brick wall in the sky.

“Hey, Ridley, that Machmeter is acting screwy,” Yeager said cooly. “It just went off the scale on me.”

“Son, you is imagining things,” Ridley replied.

“Must be. I’m still wearing my ears and nothing else fell off, neither,” Yeager joked.

On the ground, Glennis was waiting. Yeager hitched a ride back to base on a fire truck and collapsed in the car with her. “I’m beat,” he said. “Let’s go home.” But as soon as Glennis turned the ignition, two of Yeager’s buddies ran up to the car and began patting him on the back, whooping and hollering. “That’s how I found out that Chuck had broken the sound barrier,” Glennis recalled.

That historic flight transcended not only the race for space, but Chuck Yeager’s life as well. It took a year for the Air Force to release the news to the public; but when it did, the hillbilly from West Virginia became a household name. He was on the cover of TIME magazine, befriended by the most powerful men and women in America and asked to speak to groups across the country.

Yeager’s fabled ride on the Orange Beast ushered in a new era in aviation. Muroc, which had been renamed Edwards Air Force Base, was transformed from a small blip on the map to the ultimate destination for the hottest test pilots in the game.

“There were … other pilots,” wrote Tom Wolfe in his bestseller The Right Stuff, “with enough Pilot Ego to believe that they were actually better than this drawlin’ hot dog. But no one would contest the fact that as of that time, the 1950s, Chuck Yeager was at the top of the pyramid, number one among all the True Brothers.”

Yeager found himself swept up in the Golden Age of Flying and loving every minute. “In less than five years, a whole new Air Force was dumped in our laps for flight testing, including most of the prototypes of today’s supersonic aircraft,” Yeager wrote. “From first light to last light, seven days a week, the desert sky over the Mojave thundered.”

At Edwards, Yeager received all of the top assignments. In 1953, the Air Force was looking to set a new world speed record and called on him for the project. Bell delivered a new aircraft, the X-1A, designed to fly at twice the speed of sound.

On Dec. 12, 1953, Yeager strapped into the X-1A, fired the engines and began his climb. But there was a problem — he was blinded by the sun and couldn’t see his controls, and consequently his angle of ascent was too steep. He reached 80,000 feet (the outer limits of the atmosphere) at 2.4 Mach, setting a new record, but he was moving too high and too fast and his plane rebelled. The X-1A began rolling and spinning toward the desert floor.

“I was crashing around in that cockpit, slamming violently from side to side, front to back, battered to the point where I was too stunned to think,” Yeager recalled in his autobiography. “Terrifying.”

He radioed Ridley. “I don’t know whether or not I can get back. I gotta save myself. I don’t know if I’ve torn up this thing or not, but Christ …” he sobbed.

But he somehow managed to regain control of the X-1A at 5,000 feet. “You won’t have to run a structural demonstration on this damned thing,” he joked. He had cheated death once again.

“I don’t know of another pilot who could have walked away from that one,” noted Gen. Albert G. Boyd, First Commander, USAF Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base. “The gyrations were so severe that there was an indentation on the canopy where he struck it with his head. He bent the control stick. Chuck knew he was going to die. No pilot could listen to the tape of Yeager’s last ride in the X-1A without getting goosebumps. One moment, we’re listening to a pilot in dire circumstances … . In less than a minute, he’s back in control and cracking a joke. It’s the most dramatic and impressive thing I’ve ever heard.”

The Yeager legend grew. He was asked to fly around the world to test other aircraft, reel off more speeches and receive awards from several presidents, including Truman, Eisenhower and Ford. His career then took him from a seven-year stint in the desert, where his wife and four children lived in a one-bedroom house without a neighbor in sight, to Germany, where Yeager served as squadron commander for a wing of fighter pilots. The one-time young hotshot was now the “Old Man,” but his flying skills were still sharp — as many of the young pilots under his command learned the hard way.

“There was a helluva line of eager young pilots anxious to jump our new squadron commander and see what he was made of,” recalled Emmett Hatch, one of the men in his wing. “Testing Yeager turned out to be a massacre. He waxed everybody, and with such ease that it was shameful.”

By 1963, Yeager was back at Edwards and eyeing another record — this time, the altitude mark of 113,890 feet held by the Russians. On the afternoon of December 12 (10 years to the day that he nearly died breaking the world speed record in the X-1A), with Glennis and his mother looking on, he took off in a Lockheed NF-104 and began climbing toward the heavens. He exceeded Mach 2 and reached an altitude of 104,000 feet when the nose of his aircraft pitched, then fell flat and began spinning violently. Suddenly, the airplane lost its hydraulic pressure; Yeager knew he was in trouble. The NF-104 made 14 flat spins before finally punching a hole in the desert floor. Yeager managed to eject after 13. While falling from the sky, he was slammed in the face by the tube end of his seat which was still burning. The rubber seal around his helmet lit up, and the pure oxygen environment around his head ignited. The inside of his helmet was a combination of fire and smoke as he struggled to breathe. He somehow managed to rip off his helmet but in the process badly burned his hand. His left eye was burned and covered with layers of baked blood. When he hit the ground, a civilian ran toward him, saw his face and turned away in disgust. Yeager’s face was charred. He asked the young man for a knife and said, “I’ve gotta do something about my hand. I can’t stand it anymore.” He then cut off his glove, but part of two fingers peeled away with it. The young man became sick.

Yeager spent the next month in a hospital. His left eye was saved because the layers of baked blood had shielded it from the fire inside his helmet. However, his face and neck were badly burned, and the only way to prevent permanent scarring was to scrape away the scabs every four days — an extremely painful procedure.

In 1966, Yeager was assigned as the commander of the 405th Fighter Wing in the Philippines. He oversaw five squadrons involved in the Vietnam War and took part in 127 combat missions. He had served his country in virtually every capacity, from a lowly junior maintenance officer to combat ace to research test pilot. He, Glennis and their children had endured the worst possible housing conditions, low pay and, oftentimes, isolation from friends and family. But Yeager had persevered and worked his way through the ranks without ever complaining. In fact, he simply loved his work. In 1968, after 25 years in the Air Force, Yeager was promoted to the rank of general.

In 1975, he finally decided to call it quits. Those in attendance at his retirement ceremonies included fighter pilots and millionaires, test pilots and generals — as well as a few drunks. “It was a typical Yeager crowd,” Bud Anderson noted.

But retirement wouldn’t slow Yeager down. He continued to work for the Air Force and private companies as a high-priced consultant, joking that he earned as much as $1 per year for the privilege of flying all the newest jets. Yeager and Glennis bought a home in Grass Valley, California, just at the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas, where they ran Yeager Inc., a business to handle all of Yeager’s requests for speaking engagements, appearances, you name it. In many ways, Yeager was as busy as ever now that he had been thrust into the “hero business.” With the release of Tom Wolfe’s bestseller The Right Stuff, the movie of the same title, Yeager’s autobiography and his popular ACDelco commercials, he was one of the most sought-after men in America.

As time passed, his legend continued to grow, especially among the “fraternity.” In fact, Yeager had such an impact on aviation that he actually began to change the way other pilots spoke. It was his coolness under pressure combined with his distinctive West Virginia drawl that transformed the dialect of an entire generation of pilots.

“That voice,” Tom Wolfe wrote in The Right Stuff, “started drifting down from on high. At first the tower at Edwards began to notice that all of a sudden there were an awful lot of test pilots up there with West Virginia drawls. And pretty soon there were an awful lot of fighter pilots up there with West Virginia drawls. … Military pilots and then, soon, airline pilots … began to talk in that poker-hollow West Virginia drawl … . It was the drawl of the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff: Chuck Yeager.”

Airline pilots throughout the country began mimicking his style. Whenever passengers boarded a plane, they would hear that homey, cool, everything is A-OK, hillbilly voice lulling from the cockpit: “It might get a bit choppy up there today, folks, but it’s nothin’ to worry yourselves about. Those air pockets are just little ol’ bumps in the road.” And perhaps that says it all. Only Chuck Yeager could make a West Virginia accent enviable.

In the early 1980s, Yeager walked into the living room of his Grass Valley home and saw a pile of medals, trophies, letters and pictures that spanned the length of his career. “Hey, honey, what’s goin’ on here?” he asked Glennis. “Are we moving, or what?”

“No, you’re giving it away — to Marshall University,” she replied. Glennis had been working with Marshall to establish a Yeager Scholars program designed to lure the finest students from around the country to Huntington. “Only The Best” was the program’s motto. The university was also interested in a collection of memorabilia for permanent safekeeping.

On Oct. 14, 1987, Huntington and Marshall University honored Yeager on the 40th anniversary of his breaking the sound barrier. That day, he was also honored in his hometown of Hamlin with the unveiling of a life-size statue that stood in front of the local high school. Yeager thrilled all those in attendance by performing a flyby in an F-4. He swept down over the streets in a thunderous charge and displayed his signature slow roll. In Hamlin, the entire city turned out to hear their hometown hero give a speech. Children were let out from school and crowded close to the podium, eager to hear Yeager’s words.

“There was one particular boy right in front who was looking up with absolute adoration,” Bud Anderson wrote in Press On!, the popular follow-up to Yeager’s autobiography. “He appeared to be about nine and I noticed that a couple of times he even started the applause in response to Chuck’s remarks. Later, Chuck told me that this one boy grabbed his leg and asked Chuck to hold him. Chuck picked the kid up and as he was giving him a big hug, the boy pressed his head on Chuck’s shoulder, clinging like a limpet. Chuck is not one to ever show much emotion or enthusiasm for these kinds of affairs. But he was truly moved by this outpouring of admiration from the people of his hometown.”

Although Yeager will always be inexorably linked with breaking the sound barrier, his life yielded far more. From his humble beginnings in Hamlin through his highly active retirement, he was wealthy beyond most men’s dreams. Along every step of the way, he appreciated what life afforded him. Whether it was the joy of traipsing through the woods of West Virginia, the thrill of air combat in World War II, the challenge of research flying, hunting and fishing around the world or his relationships with his wife — Glennis for 45 years until her death in 1990, and later Victoria whom he married in 2003 — children and friends, he embraced life.

“I’ve had a full life and enjoyed just about every damned minute of it because that’s how I lived,” he wrote in his autobiography. “My beginnings back in West Virginia tell who I am to this day. My accomplishments as a pilot tell more about luck, happenstance and a person’s destiny. But the guy who broke the sound barrier was the kid who swam the Mud River … or shot the head off a squirrel before school.”

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Yeager’s legacy is that he was someone who men and women, young and old, aspired to be. Although his legend looms larger than life, he never forgot his roots or relented in his pursuit of being the best. And everyone, at some point in his or her life, has longed to be the best at something. Everyone has dreamt of living life to the fullest. Chuck Yeager, the hillbilly from West Virginia who flew like a demon and never backed down from a challenge, epitomized that hunger in all of us and defined what it truly means to be rich.