Founded 150 years ago on the banks of the Ohio River, Huntington has a proud past and exciting future.

By James E. Casto

HQ 113 | SPRING 2021

Collis P. Huntington was a dreamer. Not a head-in-the-clouds type of dreamer, mind you, but a man who always had both his big feet solidly planted on the ground.

When Congress called for construction of a great transcontinental railroad, Huntington didn’t just dream about that historic project; he made sure his railroad, the Central Pacific, was awarded the contract to construct the western half of the line. On May 10, 1869, a golden spike was driven at Promontory, Utah, linking the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific, which had built the line’s eastern half.

With the continent spanned, Huntington immediately threw himself into another project — a new railroad connecting the Tidewater section of eastern Virginia with the Ohio River, thus speeding the journey of passengers and cargo.

In 1869, Huntington sent a message to Oneonta, New York, asking his brother-in-law Delos W. Emmons to accompany him on an exploring trip westward across the then-new state of West Virginia. Their journey would take them along the route proposed for the new tracks of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. Left all but bankrupt in the wake of the damages it had suffered during the Civil War, the C&O desperately needed capital to rebuild and expand. The railroad’s board of directors turned to Huntington for help. He agreed to supply the money that was required — and, in the process, installed himself as the C&O’s president.

It was on this trip that Huntington first glimpsed an attractive tract of land along the Ohio River and envisioned there the city that now carries his name. The site he selected was a stretch of farmland just downstream from the mouth of the Guyandotte River, not far upstream from where the Big Sandy River flows into the Ohio and the three states of West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio meet.

At Huntington’s direction, Emmons purchased 21 farms totaling 5,000 acres and hired Rufus Cook, a Boston civil engineer, to design a town plan, one that featured a perfect geometric grid of intersecting avenues and streets, each consecutively numbered so that any address would be easy to find.

On Feb. 27, 1871, the West Virginia Legislature approved an act incorporating the City of Huntington. On December 31 of that year, Peter Cline Buffington was elected the new city’s first mayor.

Organized in 1872, the First Congregational Church is said to be the city’s oldest church. Huntington today is home to more than 150 congregations, representing virtually every faith. That includes seven congregations located in a six-block stretch of downtown Fifth Avenue and may be why some people dub Huntington the “City of Churches.”

On Sept. 6, 1875, armed bandits robbed the Bank of Huntington and made a successful escape by horseback. Local legend says the robbers were members of the infamous Jesse James gang.

The young community grew rapidly and by the early 1890s had a population of more than 10,000. In 1887, after considerable controversy, the seat of Cabell County was moved from Barboursville to Huntington.

In selecting a site for his new city, Huntington chose well. The community prospered as a gateway to the coalfields of southern West Virginia. Coal flowed from the mines to market via Huntington, and manufactured goods traveled the other direction, a two-way traffic flow that spawned jobs in the river city. In addition to its role as a transportation hub and a center of retail and wholesale trade, Huntington also attracted manufacturers who produced a broad array of products, including rail cars, steel, glass, china, brick, stoves, furniture and even church pews.

Black laborers played a major role in constructing the C&O, and many stayed in Huntington to help build some of the city’s first buildings. In the 1870s, the Rev. Nelson Barnett walked from Buckingham County, Virginia, to Huntington. Arriving, he found a booming town that clearly needed workers. He returned to Virginia and brought back a wagonload of men to work for the C&O. Most of their names are lost to history, but we know that one was James Woodson, the father of Carter G. Woodson.

A graduate of Douglass High, Huntington’s former Black high school, the younger Woodson went on to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard University. He is nationally recognized as the Father of Black History, yet he long went virtually unremembered and acknowledged in Huntington. Fortunately, that has changed dramatically. Today a handsome statue of the famed Black educator stands at the Carter G. Woodson Memorial Apartments. In a sense, it’s a statue that honors not just one man but the many Black citizens who helped build Huntington into the community we know today.

In 1909, the citizens of Central City voted to be annexed into Huntington. Two years later, voters in Guyandotte did the same.

Today, the city of Huntington is known for its broad, tree-lined streets; for beautiful Ritter Park, fashioned in 1913 from land originally intended for use as a city incinerator; for the grand Keith-Albee Theater, which has welcomed audiences since 1928; for the impressive Cabell County Courthouse, dedicated in 1901; and, of course, for Marshall University.

Older than the city itself, Marshall was established in 1837 in a log church on the hill where Old Main now stands. Marshall has grown steadily over the years, especially since it became a university in 1961. Today, Marshall’s many students are enrolled in a broad range of academic programs. Its Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, which admitted its first class in 1978, has helped make the city a regional health care center. And Marshall’s sports teams are a source of community-wide pride.

On Nov. 14, 1970, a chartered jetliner crashed at Tri-State Airport, killing all 75 aboard — members of the Marshall football team, five coaches and athletic officials, the plane’s crew members and a number of the community’s leading citizens who were traveling with the team. Decades later, the emotional wounds of the plane crash remain. Some scars never heal.

In April 2006, filming began in Huntington for We Are Marshall, a major motion picture depicting the plane crash and the remarkable comeback of Marshall football that followed. Members of the MU community and townspeople got a chance to serve as extras in the film, which premiered later that year at the Keith-Albee.

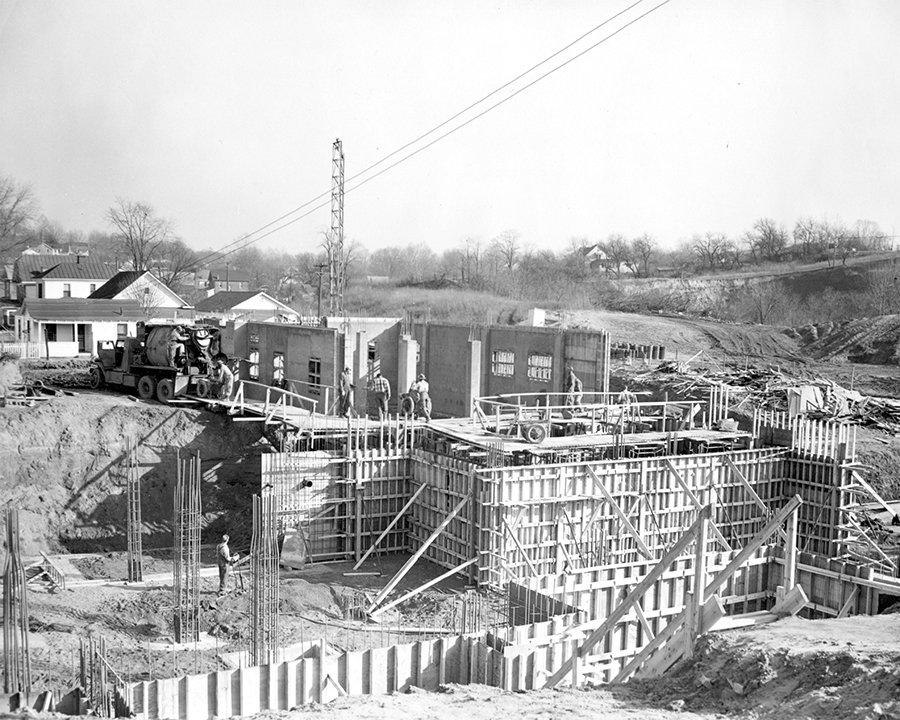

Flooding was a continuing problem in Huntington for many years. Major floods occurred in 1884 and 1913, but the worst occurred on Jan. 28, 1937, when the river inundated much of the city. The river crested at a record 69.45 feet, more than 19 feet above flood stage. Following the disaster, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed an 11-mile floodwall to protect the city from future floods. Unfortunately, the floodwall also meant the Ohio was now hidden from view, prompting the city to forget its historic ties with the river. That was corrected in 1984, with the opening of the David W. Harris Riverfront Park.

Over the years Huntington continued to grow and prosper. That prosperity came to an abrupt end, however, in October of 1929, when the stock market crashed. Hundreds of people in Huntington soon found themselves without jobs as factories closed and businesses failed. Of the 11 banks operating in Huntington during the 1920s, only two survived as the Great Depression deepened.

It took the outbreak of World War II to put Huntington, like the rest of America, back to work. The city’s factories shifted to war production and worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week. With so many men away in uniform, women workers made their way onto the factory floors for the first time.

With the war’s end, the 1950s proved a decade of remarkable growth and achievement for Huntington — the city’s zenith, some would argue. The decade saw the construction of Tri-State Airport, the Huntington Museum of Art, Cabell Huntington Hospital and the Veterans Memorial Field House.

Sadly, in the following decades Huntington saw many factories close, businesses slump and jobs disappear. Part of the decline stemmed from sweeping cutbacks in coal mine employment as automation took hold in the surrounding coalfields. Some saw the decision to route Interstate 64 around Huntington as a tragic mistake, and the later building of the Huntington Mall in Barboursville dealt a body blow to many downtown businesses.

The city’s economic woes were reflected in a dramatic population decline. Huntington lost nearly 35,000 residents from 1950 to 2000, leaving a population of 51,475. In the 2020 Census, the city’s population was 45,110, an 8.3% decline from 10 years before. Some residents simply moved to growing suburban areas outside the city, but many left the region, seeking better opportunities elsewhere.

The Huntington of the 1950s is gone and isn’t coming back. But it would be a serious error to argue that the city’s best days are behind it. There’s much that today’s Huntington can be proud of and encouraged by — the dramatic growth of Marshall University, the city’s rise as a major medical center, the new schools that have been built and of course the construction of Pullman Square, the retail/restaurant/entertainment complex that’s breathed new life into the downtown.

Like many other communities, Huntington has been hit hard by the opiod crisis. But working together, the city, the university and the medical community have created a number of truly revolutionary programs that are recording impressive success — generating a decline in overdoses, an increase in referrals to treatment and a reduction in drug-related crime.

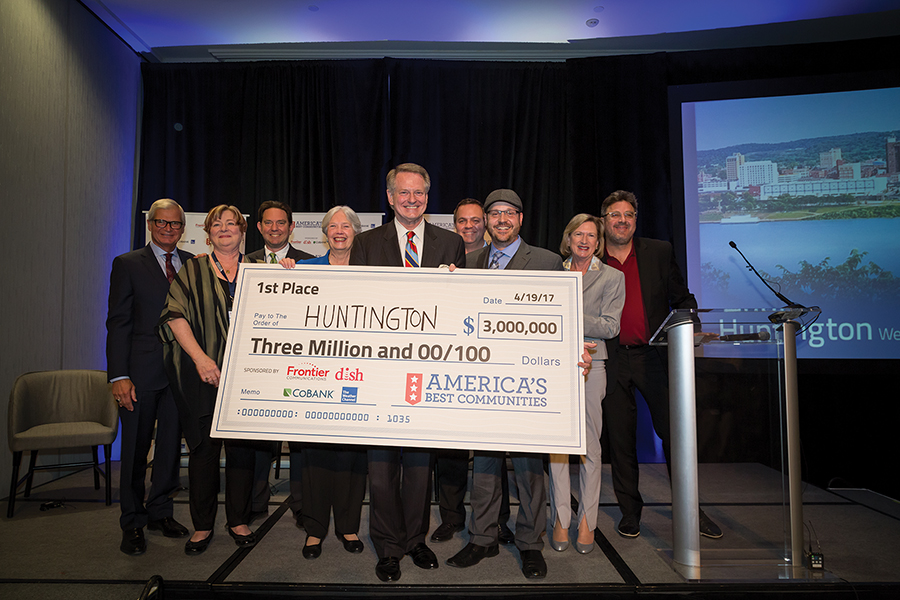

In 2017, Huntington bested more than 350 other towns to claim the title of “America’s Best Community” when it was named the $3 million grand prize winner in a nationwide competition.

Huntington garnered the prize after spending three years crafting an ambitious redevelopment plan for the city, the Huntington Innovation Project. The project is broken into four parts, three of which are devoted to specific neighborhoods — the West End, Fairfield and Highlawn. The fourth part is aimed at helping bring high-speed broadband to the Huntington region.

In 1869, Collis P. Huntington stood on the banks of the Ohio, looked out over a tract of vacant river bottomland and envisioned there a busy city, one teeming with stores and factories, schools and homes. Today, as Huntington celebrates its 150th birthday, the rail tycoon’s dream is a city with a proud past and an exciting future.