The story of how fate interceded to bring five talented football players from Druid High School in Alabama to Marshall.

By Jack Houvouras & Keith Morehouse

HQ 116 | WINTER 2022

The year was 1970, and there were five young men on the roster of the Marshall University Thundering Herd football team who all had something in common. In addition to being exceptional athletes, all five came to Huntington by way of Druid High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Druid was the only high school for Black students in grades 8-12 in Tuscaloosa in the 1960s, and it was a legendary reservoir for high school football talent.

Considering the fact that Druid was located in the same town as the University of Alabama, one might wonder why these talented athletes didn’t play football for the Crimson Tide. Well, that was a different time in America, especially in the Deep South. The country was just emerging from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and not everyone embraced the social changes. Those black and white pictures of water hoses and police dogs are searing images of a virulent time in the South. As a result, the University of Alabama did not recruit any Black players at the time. Historians and biographers have often wondered — was it Bear Bryant who wasn’t ready for Black football players, or was it the state of Alabama?

For Joe Hood, Larry Sanders, Robert VanHorn, Freddie Wilson and Reggie Oliver, they would have to travel north to play college football. The story of how they found their way from Tuscaloosa to Huntington is a forgotten piece of Thundering Herd history.

As a junior in high school, Joe Hood was considered one of the best high school players in all of Alabama. The remarkably fast and elusive running back led the Druid High School Dragons to a 10-0 record and was creating quite a buzz across the state. In fact, during the spring of Hood’s senior year, Bear Bryant wanted to see him. Paul William “Bear” Bryant, that is. The legendary coach of the Alabama Crimson Tide and winner of six national championships knew a good football player when he saw one. Problem was, segregation was still a way of life in Alabama.

“Joe showed up for the meeting, but it never happened,” recalled his brother Jerome Brown. “Bear Bryant had changed his mind and refused to see him. Joe was upset. He said, ‘Bear Bryant doesn’t have to worry about me ever playing for him.’”

Enter Marshall University. The Herd already had a Tuscaloosa connection on its football roster. Druid’s Larry Sanders had come to Huntington in 1968. The 6-foot-2, 190-pound defensive back led the team with five interceptions in 1969. Sports Information Director Gene Morehouse wrote this of Sanders in the 1970 media guide: “Sanders has the size, strength, and ruggedness to be an outstanding professional prospect once his collegiate career is over.”

When Bryant stood up Hood, Marshall pounced. The Herd’s running back coach at the time was Mickey Jackson. A star running back himself at Marshall who scored 16 touchdowns in 1964, by 1970 he had become the university’s first African American coach. He was licking his chops at the chance to work with Hood.

“He was unbelievable,” Jackson said. “I could not wait to coach him. He was the first large back over 6 feet tall and 200 pounds. He had speed, coordination and toughness.”

Red Dawson, another assistant coach at Marshall at the time, knew all about Druid as well. He learned about the high school from none other than Bear Bryant himself. Dawson met the famous coach when Bryant was recruiting his younger brother Rhett, who went on to play at Florida State. As such, Dawson saw Druid as a pipeline to broaden the football program’s recruiting horizons. He scouted more outstanding players at Druid High including Freddie Wilson, a sure-handed tight end who was a particularly good blocker. He also eyed Robert VanHorn, who he thought had all the makings of a solid defensive lineman.

“I called him (Bear Bryant) up and told him I wanted to come to Tuscaloosa and see those players,” Dawson recalled. “Coach Bryant told me, ‘If I could have recruited those boys I would have done so already.’”

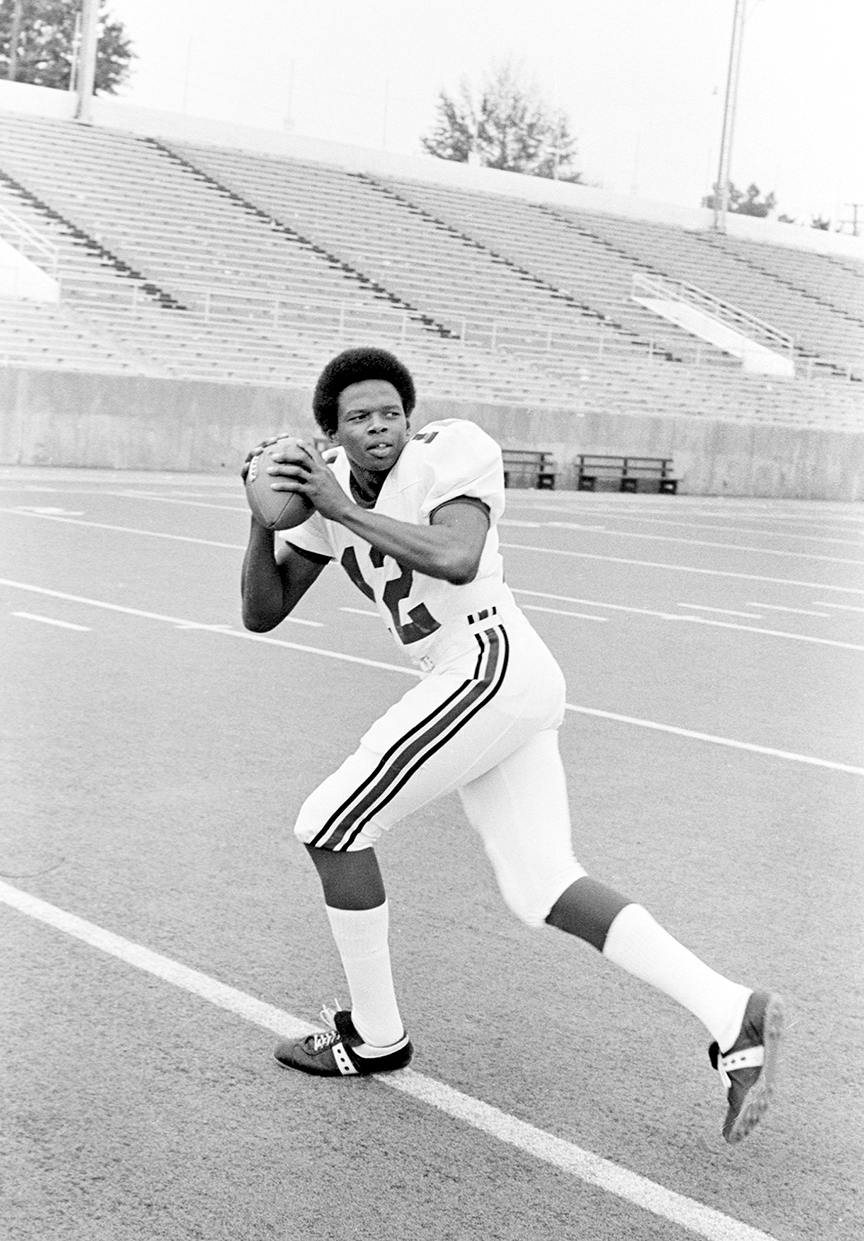

There was one more Druid star football player who came to Marshall — Reggie Oliver was a star quarterback and another Dawson signee.

“Well, Joe, Freddy, Larry and Robert were all at Marshall and I thought, ‘If it’s good enough for them it’s good enough for me,’” said Oliver.

“I think those were five of the classiest football players that we got from Tuscaloosa,” Dawson recalled recently. “I’m not patting myself on the back for recruiting them, but they liked it here.”

With the addition of these gifted athletes, the future of the Thundering Herd football program looked bright in 1970. But fate did not smile on four of the five Tuscaloosa boys. On Nov. 14, 1970, while returning from a game against East Carolina, the plane carrying the football team crashed in fog and rain just short of the Tri-State Airport runway. All 75 souls on board were lost in an instant. To this day the tragedy is the worst in the history of collegiate athletics.

Members of the Young Thundering Herd attend practice on Sept. 12, 1971.

However, Dawson, Jackson and fellow assistant Carl Kokor were not on the plane because they had plans to drive back following the game and do some recruiting along the way. The three men have been forced to live with the aftershocks all these years later.

The four funerals were held simultaneously at Druid High in Tuscaloosa one week after the crash.

“Reverend Charles Smith came down to do the eulogy,” Brown recalled, before pausing for a moment while searching for words. “I was listening so intently to find something that he was saying that would give me some relief. He said, ‘You know, the Lord doesn’t make any mistakes. He has a rose garden up in heaven, and he picked only the best to go into his garden.’”

Oliver missed the flight because he was just a freshman. In 1970 freshman athletes were not permitted to play varsity sports. As a result, they did not travel with the team to away games. In the days after the crash the 18-year-old was tasked with identifying the remains of his teammates.

Oliver lost part of his soul that day. As he told The New York Times in 2000, “Not a day goes by when I don’t think of the plane crash. I remind myself: ‘Live life to the fullest. Nothing is promised.’”

Actor Arlen Escarpeta, right, listens as former Marshall quarterback Reggie Oliver speaks about the Young Thundering Herd on Saturday, June 10, 2006, during the filming of “We Are Marshall” at Herndon Stadium at Morris Brown College in Atlanta. The movie depicts the fight to maintain Marshall’s football program following the 1970 plane crash that claimed 75 lives including Marshall football players, coaches, community members and flight crew. Escarpeta portrays Oliver in the movie.

Following the plane crash Oliver was given the opportunity to leave Marshall, but he chose to come back and play for the Young Thundering Herd in 1971. Coaches Dawson, Jackson and Kokor also decided to return as assistant coaches. That year, with the weight of the world on his shoulders, Oliver emerged as the heart and soul of a team comprising mostly freshmen. Then, on Sept. 25, 1971, with the final seconds ticking off the clock, Oliver threw the most important pass in Marshall football history — a 13-yard screen to running back Terry Gardner who scampered into the endzone as time expired, giving the Herd a 15-13 upset win over Xavier in its first home game after the plane crash. For obvious reasons, that victory is considered the greatest in school history.

Oliver was Marshall’s starting quarterback for the next three seasons, setting several school passing records along the way. He was inducted into the Marshall Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984.

At a Memorial Fountain ceremony in 2018, Oliver told a rapt audience, “Don’t forget them. Don’t let them think that we went from Nov. 14 to winning bowl games and getting rings and living large. Remember those people who put the first bricks in the foundation.”

On Nov. 13, 2021, a retired newspaper reporter from Tuscaloosa penned a column about his memories of the night of the plane crash. Stan Voit was just 20 years old when the news of the plane crash rattled out of the Associated Press Teletype machine in the offices of The Tuscaloosa News. It was then Voit’s job to write the news article for the next day’s edition.

“I always thought that having four players from one high school to die in that crash should have gotten more national attention, but it never did,” Voit wrote in 2021. “I have retired after a long career in the newspaper business, but no story I ever did meant more than the one I pieced together that night in 1970. I can never see any reference to Marshall without thinking of those four lost souls.”

On Aug. 14, 2018, Reggie Oliver fell and hit his head at his home in Huntsville, Alabama. He was admitted to the hospital where he died a week later. He was 66. He was then buried at Cedar Oak Memorial Park in Tuscaloosa where he rejoined teammates Joe Hood, Larry Sanders, Freddie Wilson and Robert VanHorn.

In 2020, a city block located at the intersection of Huntington’s 14th Street and Charleston Avenue was designated Honorary Reggie Oliver Square. Huntington Mayor Steve Williams said the site was chosen for a reason.

“The one significant place for Reggie in his time here in Huntington was at Fairfield Stadium, and this entire area is where Fairfield Stadium was,” Williams said. “Reggie Oliver meant everything to those of us who came to know him and love him. He loved Marshall University and he loved Huntington, West Virginia, and we’re here to pay him honor.”

“When you talk about the essence of the greatest comeback story in the history of sports, you talk about Reggie Oliver,” said Mike Hamrick, Marshall University’s athletic director at the time. “I’ve never been around a person who loved and cared about this university and this community more than Reggie Oliver.”

Epilogue: In 1970 Bear Bryant invited the University of Southern California to play his Alabama team in Tuscaloosa. The USC squad, which featured several Black players, soundly defeated the Crimson Tide 42-21. The following year Alabama began recruiting African American athletes. That historic game and its social ramifications are the subject of a 2020 documentary film titled Against the Tide.

In 1979, Druid High School merged with the all-white school Central High.