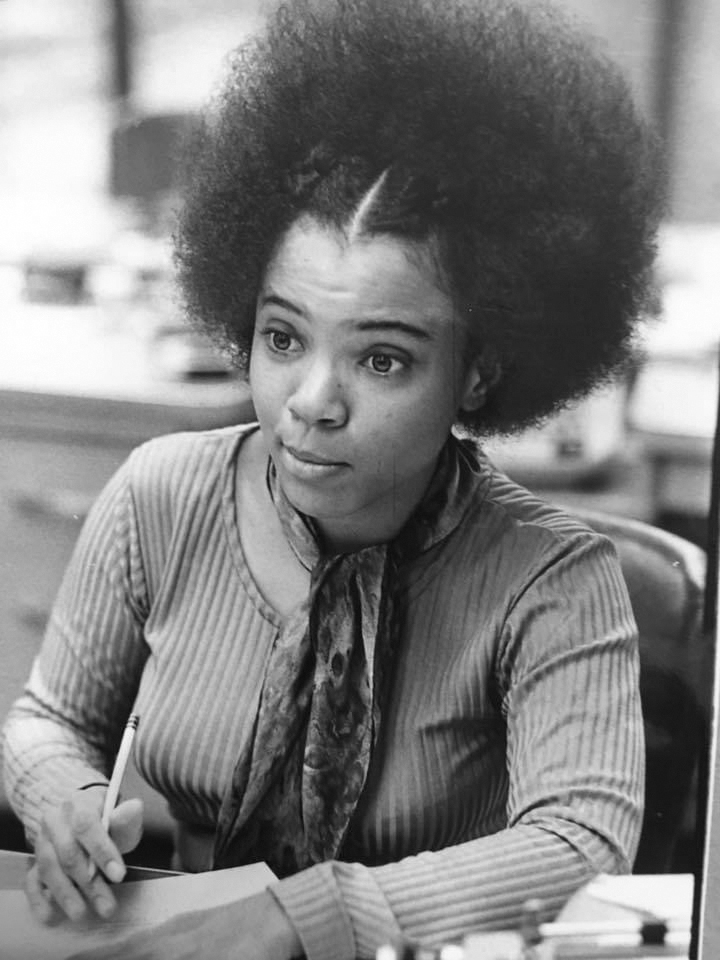

Meet Angela P. Dodson, a Marshall alumna and the first Black female senior editor of The New York Times, whose journalism career is newsworthy itself.

By Katherine Pyles

HQ 120 | WINTER 2023

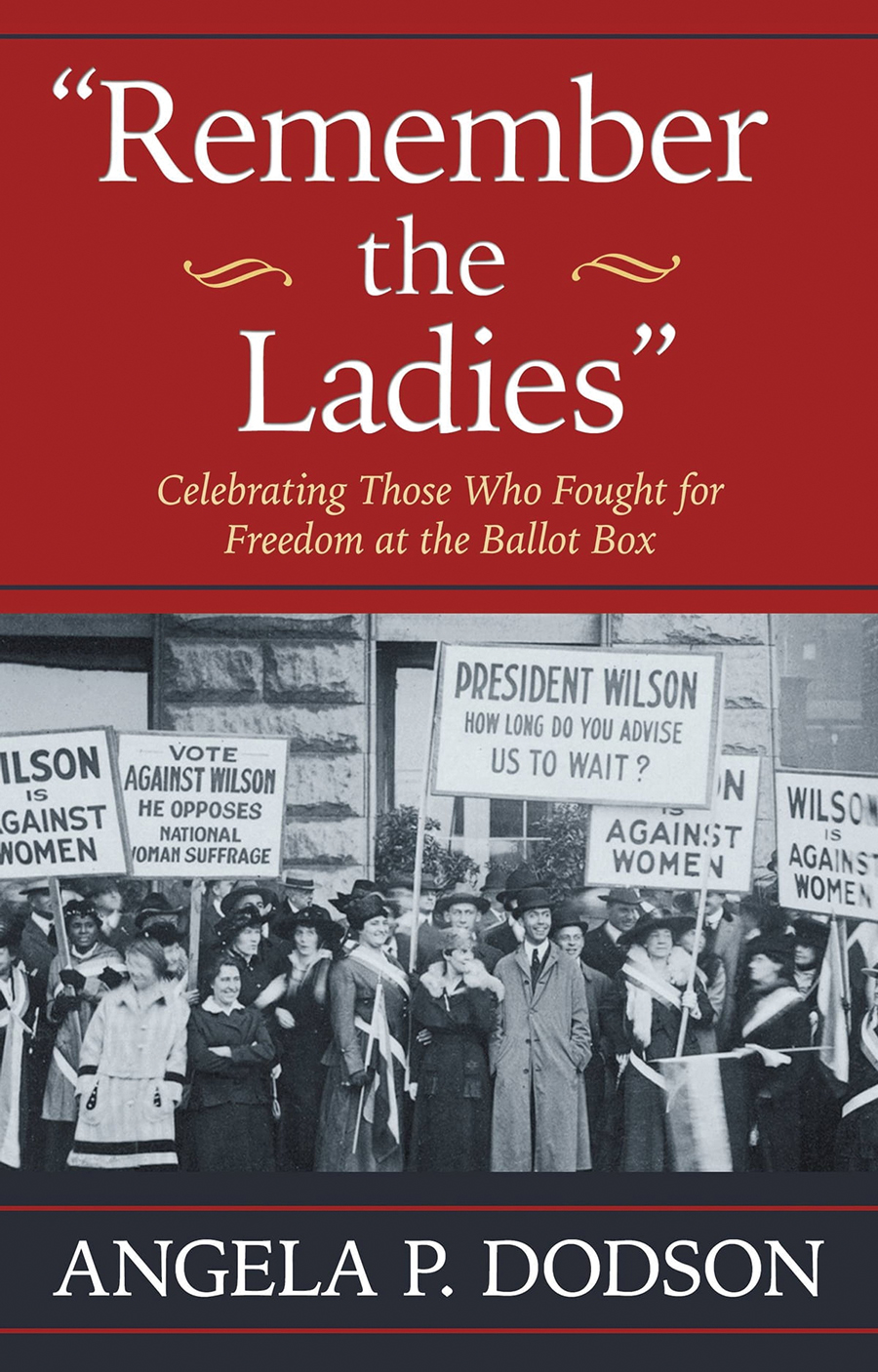

Even if you don’t know the name Angela P. Dodson, you probably know her work. If you’re a longtime reader of The New York Times, you’re likely acquainted with her editorial eye: Dodson joined the newspaper as a copy editor in 1983, then worked as the Style editor before becoming senior editor for administration in 1992 — the first Black female senior editor in NYT history. If you’ve studied the women’s suffrage movement, perhaps you’ve read her book Remember the Ladies: Celebrating Those Who Fought for Freedom at the Ballot Box. And if you lived in Huntington during the Watergate scandal, you might remember her coverage of the aftermath in The Huntington Advertiser, where she was the paper’s first Black reporter.

She’s led a storied career, covering historic moments while simultaneously making history herself. But for the Beckley native, Marshall alumna and adoptive mother of four, the story of her career is simply one of “unexpected blessings.”

“A lot of it happened by accident,” she said.

Dodson knew from an early age that she wanted to be a writer.

“I’ve loved writing since I first learned to read,” she said. “I told my parents when I was 11 that I wanted to be a journalist. I don’t even know where I learned the word, but that’s what I wanted to be.”

Dodson’s family left West Virginia for Pennsylvania for several years, then returned to the Mountain State when Dodson was a teenager because her father had gotten a job with the Federal Aviation Administration. Heavily recruited by schools like Brown and Michigan State, Dodson chose to attend Marshall.

“My older brother went to Marshall the year before I did, and I had cousins who went there, beginning in the 1960s,” explained Dodson, who lived just outside of Charleston during high school and college. “I loved Huntington as soon as I saw it.”

At least a dozen members of the Dodson-Hairston family have attended or graduated from Marshall. In 2018, Dodson and her family established the Dodson, Dotson and Hairston Family Scholarship to benefit Marshall students from southern West Virginia.

“I might never have known some of my Dotson cousins had we not all met at Marshall and realized we were related,” Dodson said. “Our great-grandfathers were brothers who moved to West Virginia from Virginia, and somewhere along the way the name spelling got changed for one of them.”

At Marshall, Dodson was one of the first four members initiated into the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. in 1972 and helped found the university’s chapter of the sorority — an international organization founded by Black women at Howard University in 1908. Founding members of the Marshall chapter celebrated their 50th anniversary last year during homecoming.

Her junior year, Dodson’s professor and mentor Dr. Ralph J. Turner selected her for a summer internship at The Charleston Gazette. When classes resumed that fall, Dodson planned to focus only on her studies; but another local paper, The Huntington Advertiser, had its sights set on the J-School’s rising star.

“I had heard they were looking to hire ‘a Black journalist,’” she recalled. “I was reluctant to go in for an interview if they were just looking for any Black journalist they could find. But what I didn’t know was that [editor] Don Hatfield had been reading me for some time in [Marshall’s student paper] The Parthenon. Ralph convinced me to go, and Don hired me on the spot.”

The Advertiser was an afternoon paper, so Dodson worked in the mornings and attended classes in the afternoons. As for being the paper’s first Black reporter, Dodson said prejudice was a non-issue in the Advertiser’s newsroom.

“The staff at the Advertiser was very small, and we were very close,” Dodson said. “A bunch of us just went to lunch during Marshall’s homecoming. There was no competition — there were just the six or seven of us trying to get the paper out every day.”

Dodson continued to work at the Advertiser after graduating in 1973. In 1974, her colleagues helped her land a job at Gannett News Service in Washington, D.C. Dodson interviewed for the position just days before President Nixon’s resignation.

“By the time I got back from the tryout, Nixon had resigned,” she recalled. “I helped cover the resignation from Huntington, then moved to Washington later that fall.”

Dodson worked for Gannett for several years, taking a weekend editor position while she worked toward her master’s degree at American University. Next, she went to work for one of Gannett’s newspapers in Rochester, the Times Union, and later returned to D.C. to work for the Washington Star before accepting a job in Louisville at the Courier-Journal. She had been pursued by the paper since her early years at Gannett, and editors approached her again. This time, she accepted.

“I think someone there knew my boyfriend lived in Louisville,” she surmised.

She left the U.S. capital for the Bluegrass State in 1980.

There, Dodson married fellow journalist Michael I. Days, whom she had met in Rochester. She was approached by The New York Times soon after. Dodson had been teaching editing in a program for minority journalists, and two of her colleagues who were from the Times recommended her for a copy editing position.

In the interview, she was told the process typically takes months and not to be discouraged if she didn’t hear back after a tryout. “No one passes this thing,” she remembered hearing. But less than two weeks after her tryout, Dodson was offered the job.

“We had just bought a house, and I was on the verge of turning it down,” she admitted. “My husband finally said, ‘Angela, no one turns down The New York Times.’”

The couple relocated to New Jersey in 1983. Her husband was hired at the Wall Street Journal’s Philadelphia bureau before joining the Philadelphia Daily News, where he was executive editor for 10 years. The pair commuted in opposite directions for almost two decades.

At a time when diversity in journalism was immensely lacking and at a publication where competition was intense, there was an element of culture shock when Dodson started at the Times.

“I always say New York City is the place valedictorians go to kill each other off,” she said, laughing. “It’s a competitive atmosphere, and everyone’s vying for something. I wasn’t that kind of person. I just went in every day and did my job.”

Even so, Dodson’s editorial talent and work ethic led to promotion after promotion. She was among few minority journalists at the Times, and the opportunity to be a “historic first” among Black journalists lay just on the horizon for her — a realization that didn’t sink in until she was promoted to Style editor in 1991.

“When I got the promotion and walked back to my department, the staff gave me a standing ovation. My office basically filled up with flowers,” Dodson recalled.

Two years later, Dodson was promoted again, making her the first Black woman to be a senior editor at the Times, helping to recruit and hire staff. While many of her colleagues were supportive, she said, there remained an “undercurrent” of prejudice and classism.

“Earlier in my career there, I was editing a story and the reporter argued with me, saying, ‘If you had ever covered the Senate, you’d know …’ I had covered the Senate, of course,” she said. “Another time I had hired a woman as a copy editor who was Black, and a reporter disagreed with her editing. He said to her, ‘Well, I went to Yale.’ And she said, ‘I did, too.’ There was an assumption among some that you couldn’t possibly be better or smarter or more qualified than your white colleagues — or that you couldn’t be right, and they be wrong — as if the Times would hire incompetent people as editors.”

Dodson left the Times in 1995, going on to hold other prestigious editorial positions for publications like Essence Magazine and Diverse: Issues in Higher Education, as well as hosting a radio program about Black Catholics. In the early 2000s, she worked as a writer and editor for Black Issues Book Review, the first large circulation magazine dedicated to books written by Black authors, and was executive editor of the publication for four years.

She got into book writing “accidentally,” she said with a smile, after her former manager at Black Issues Book Review asked if she’d be interested in doing some editing and ghostwriting for her at a major publishing house.

Today, Dodson takes on a wide range of projects, from ghostwriting memoirs for athletes to writing religious meditations. She is the CEO and founder of Editorsoncall, a company that connects clients with freelance writers, editors, graphic designers and photographers. She has worked with organizations like the National Black Writers Conference, the National Association of Black Journalists, the American Press Institute and the American Society of Newspaper Editors, often serving as a mentor to young Black journalists.

“When I was entering the profession, there weren’t many people I could go to for advice,” she said. “Mentoring is very important to me — just seeing young people come into the field and helping them the best I can.”

In her spare time, Dodson enjoys collecting art and antiques, cooking, reading and collaborating with her husband on writing endeavors. Their sons, four brothers they adopted in 1991, are grown now; and Dodson and Days have been promoted to grandparents. One of their sons, Adrian, passed away in 2022.

Grateful for the mentorship she received in Huntington and at Marshall, Dodson returns often to the place she got her start. She has addressed journalism classes, served on the board for the Society of Yeager Scholars for several years and spoken at various events. While on a book tour in 2019, she spoke to the Huntington League of Women Voters and for an assembly at Huntington High School. In 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, she did a virtual talk for the Dr. Carter G. Woodson Lyceum.

She continues to be a source of support for minority journalists making their way in a still-difficult profession.

“Minority journalists are getting ahead and getting jobs and becoming top editors, but it’s not easy for them,” she said. “The things I hear from journalists today are like déjà vu in a lot of ways. I have a lot of people that I’ve brought under my wing — people looking for advice or comfort or both.”

Reflecting on the future of journalism, she said it’s young journalists who give her hope.

“I am concerned that the field has segmented into camps of left-wing or right-wing opinion journalism, especially in broadcasting, contributing to a vast divide in our nation,” she noted. “Anchors no longer just read the news like Walter Cronkite. They yell their opinions at you. On the other hand, I am optimistic because our young journalists seem well-prepared and multitalented. They are not only making existing media exciting and informative, but they are also creating new media outlets, nationally and locally, that meet the needs of diverse audiences.”