Huntington’s own Harold Hawkins was a country music star whose career was cut short in the plane crash that also claimed the life of Patsy Cline.

By Carter Seaton

HQ 123 | AUTUMN 2023

Over the years, West Virginia has produced its share of musical phenoms: Hazel Dickens, Bill Withers, Kathy Mattea, Michael W. Smith and Brad Paisley, to name a few. But the only one born in Huntington has likely slipped from memory since his untimely death in 1963 — Harold “Hawkshaw” Hawkins.

Little Harold Franklin was born in 1921 to Alex and Icie Graham Hawkins and grew up in the West End of Huntington. His father retired from Kerr Glass Company in Altizer. Harold earned the nickname “Hawkshaw” after helping a neighbor find two missing fishing rods. The man borrowed the name from the title character of the comic strip Hawkshaw the Detective, and it stuck throughout Hawkins’ life.

Young Hawkshaw became interested in music and traded five trapped rabbits for his first guitar. He taught himself to play and soon began performing on WCMI-AM radio in Ashland, Kentucky. At age 16 he won a talent competition and earned a job on WSAZ-AM with his band — Hawkshaw and Sherlock with Clarence Jack. The bigger city of Charleston, West Virginia, beckoned in the late 1930s, and they moved to play on WCHS-AM.

In 1940, at age 19, he married 16-year-old Reva Mason Barbour from Huntington and began traveling the country with a musical revue the following year. In 1943, Hawkins joined the U.S. Army, where he served as an engineer stationed near Paris, Texas, during World War II. Still, with music in his blood, he and some buddies performed at local clubs. He was promoted to staff sergeant and fought in the Battle of the Bulge while stationed in France. He was awarded four battle stars during his 15 months of combat service, which also included a stint in Manila where he performed on local radio.

By 1945 Hawkins was a regular on the Wheeling Jamboree in northern West Virginia. This led to his first recording contract with King Records in Cincinnati, Ohio, which he signed in 1946. It almost didn’t happen, however. His demo recording was so poorly made that label founder Syd Nathan nearly threw it away without listening to it. Nevertheless, Nathan agreed to produce four of Hawkins’ songs. Two became Top 10 country hits, and another, The Sunny Side of the Mountain, became his signature tune, although it was only a minor hit for Hawkins. He stayed with King Records until 1953, but his career was well underway by then.

ABC Radio and Television’s Ozark Jubilee picked Hawkins up as a regular performer in 1954. It was there, at the home of the Jubilee in Springfield, Missouri, that he met Jean Shepherd, who would become his second wife. Although Hawkins and his first wife Reva had adopted 4-year-old Susan Marlene in 1951, they divorced in 1958. Hawkins married Jean, a fellow musician, in a public ceremony during a concert performance.

After a few years with Columbia and RCA Records, Hawkins returned to King after joining the Grand Ole Opry in 1955. Hawkins must have been an imposing onstage presence with his 6-foot-5-inch lean stature, oversized white cowboy hat, dark hair and lopsided smile. He tended to dress more conservatively than many of the others on stage, which set him apart as well. According to Ken Burns in his Country Music documentary, Hawkins was considered charismatic and outgoing. Those qualities earned him the additional nickname “Eleven Yards of Personality.”

It’s perhaps those very traits that inadvertently led to his untimely death. When beloved Kansas City disc jockey Cactus Jack Call died in an automobile accident, Hawkins was one of the first in the Opry family to volunteer to perform at a benefit for the man’s family. Before he left for the benefit, he took a demo of a recent recording — Lonesome 7-7203 — to a friendly disc jockey with the admonition to “play the hell out of it.” He signed the note, “Hawk.”

Hawkins flew to Kansas City via commercial airline, performed the benefit on March 3, 1963, at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall and prepared to return home. When another of the performers, Billy Walker, received an urgent phone call and had to return immediately to Nashville, Hawkins gave up his seat and agreed to fly home with Patsy Cline and Cowboy Copas on a private plane. Cline’s manager, Randy Hughes, was the pilot.

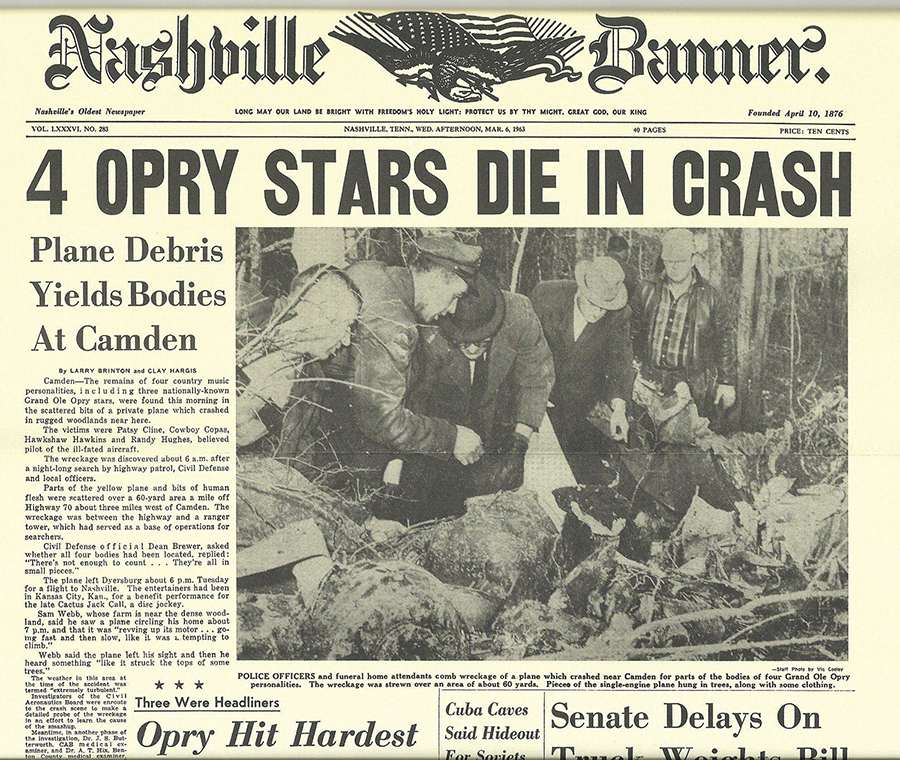

The rest of the story is history. Cline’s plane ran into bad weather and Hughes, untrained on instrument flight rules, was unable to keep it from crashing in a forest near Camden, Tennessee, 90 miles from Nashville. No one survived the March 5 accident. Hawkins’ boots, his jeweled belt and the neck of his guitar helped identify him as one of the victims. His wife Jean (who was pregnant with their second child), their son Donnie and Hawkins’ daughter Susan Marlene were left to mourn the loss, along with Hawkins’ fans worldwide.

Lonesome 7-7203 did not appear on the charts for the two weeks after Hawkins’ death, then it spent 25 weeks there, four of them at No. 1. It was an accomplishment he never enjoyed while he was alive.