The most significant news events in the region from the last 152 years, as selected by our readers.

By James E. Casto & Joseph Platania

HQ 123 | AUTUMN 2023

In today’s world the news cycle runs on a continuous loop 24 hours a day. Our televisions inform us of breaking news alerts, weather warnings, the latest sports scores and more. The internet provides endless options to stay abreast of current events, from social media to blogs to podcasts. Even our telephones can be programmed to chime when a major news story breaks.

There was a time when Huntingtonians only received their news from three sources: newspaper, radio and television. If residents wanted to know about an approaching storm, the latest Marshall football score or a local fire, most had to rely on the evening news or the next edition of the newspaper.

Looking back at the 152 years since Huntington was founded, we decided to ask our readers what news stories stand out most in their minds. The following is their list presented in chronological order. Some news is good, some bad and some tragic. Nevertheless, these are some of the stories that have defined this region since 1871.

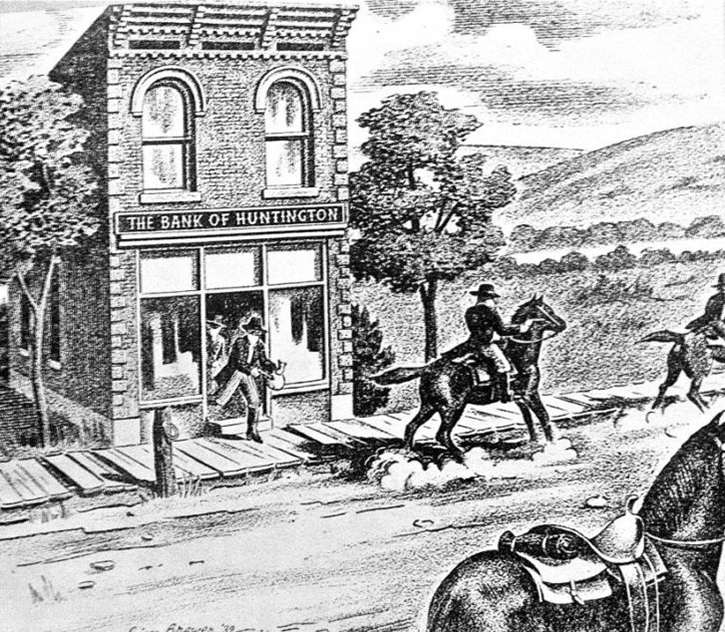

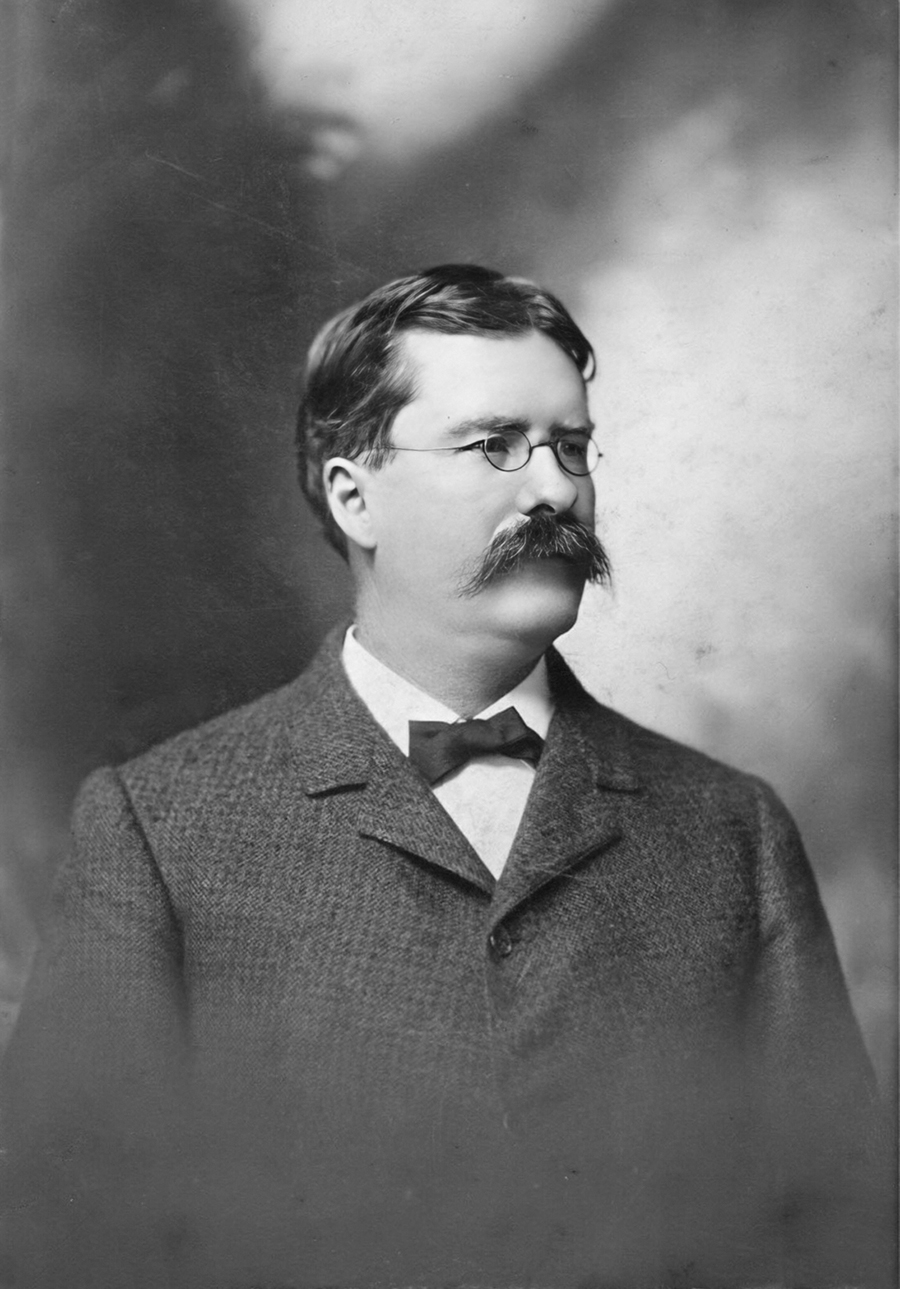

Armed Bandits Rob the Bank of Huntington

On Sept. 6, 1875, four well-armed men rode into Huntington and committed the most famous robbery in the city’s history. The original newspaper account reported that two men, with revolvers drawn, entered the Bank of Huntington while two others remained outside. Both of the inside men jumped over the counter and confronted cashier Robert T. Oney. With four revolvers drawn on him, Oney was defenseless, yet he stubbornly refused to comply with their demands. The robbers then swore they would blow his brains out unless he did as they ordered. This time he complied and handed the men two packages of money. From the newspaper’s account, the gunmen apparently liked the cashier’s spirit. They asked Oney if any of the money was his. He replied that he had about $7 in the bank. They said, “Well, we don’t want this little scrape to cost you anything,” and counted out $7 and gave it to him.

The robbers then mounted their horses, fired their pistols into the air and rode west down Third Avenue in a cloud of dust. They turned their horses south and rode full speed away from town toward Four Pole, a meandering creek that runs at the foot of the hills south of Huntington. The robbers’ escape route led them up what is now McCoy Road where the Huntington Museum of Art is located, and then down to the Wayne County line. They headed for the town of Wayne and then turned west toward the Big Sandy River.

They carried with them almost $20,000 of the bank’s money stuffed into cloth sacks. Although the men didn’t leave their calling cards, an initial investigation showed that the daring daylight robbery exhibited several characteristics of Jesse James and his gang, who were terrorizing the Midwest at the time. However, later research indicated that Jesse James was not in Huntington that day. Instead, it was most likely his brother Frank and the infamous outlaw Cole Younger, two longtime members of the James-Younger Gang.

Huntington’s First Bridge

When Collis P. Huntington founded the city of Huntington in 1871, he foresaw the day his namesake town would need a bridge across the Ohio River. He even bought a plot of Ohio land for the purpose. But the city would be more than 50 years old before its first Ohio River bridge was constructed.

The bridge was built by a group of a dozen Huntington businessmen organized by timber tycoon C.L. Ritter. In April 1925, they chose a site just west of the city’s downtown at Sixth Street and began construction. The span was opened to traffic on May 23, 1926, with an estimated 10,000 visitors on hand for the dedication ceremonies.

The bridge was privately owned until 1940 when the builders sold it to Cabell County for $2 million. By 1952, deferred maintenance had caught up with the bridge; and the county, unable to finance the badly needed repairs, was happy to turn the bridge over to the state.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, drivers waiting to cross the two-lane span clogged the city’s downtown streets at the evening rush hour. The Ohio side saw a similar traffic snarl in the mornings.

Finally, in 1968, Huntington got a second Ohio River crossing, at West 17th Street. And in 1986, after decades of controversy and delay, the East Huntington bridge was completed and opened.

In mid-1993, the Sixth Street bridge was closed to traffic to allow for construction of an adjacent four-lane bridge (the city’s first). The new bridge was completed in 1994. The following year, a series of carefully placed explosives blasted the Sixth Street bridge into history.

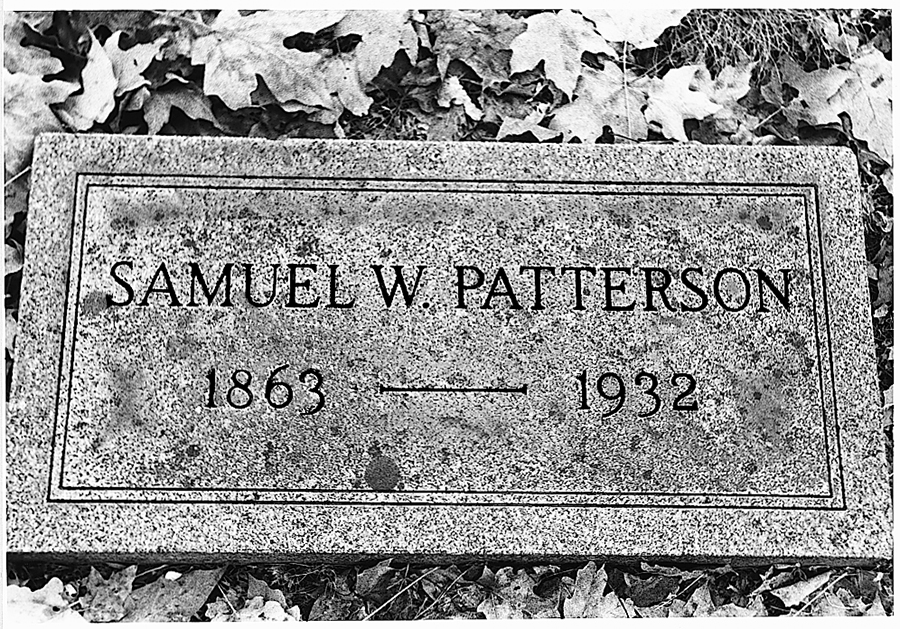

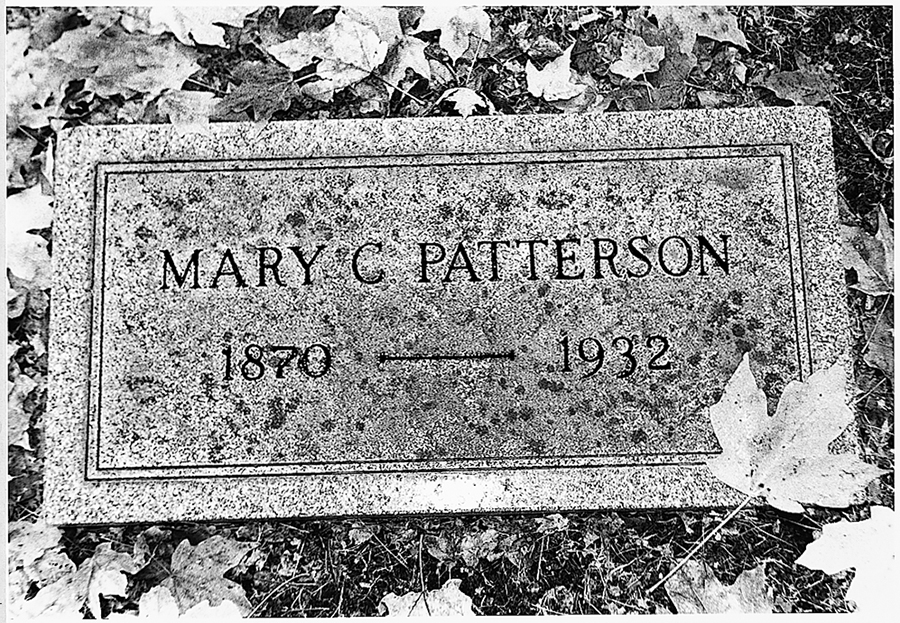

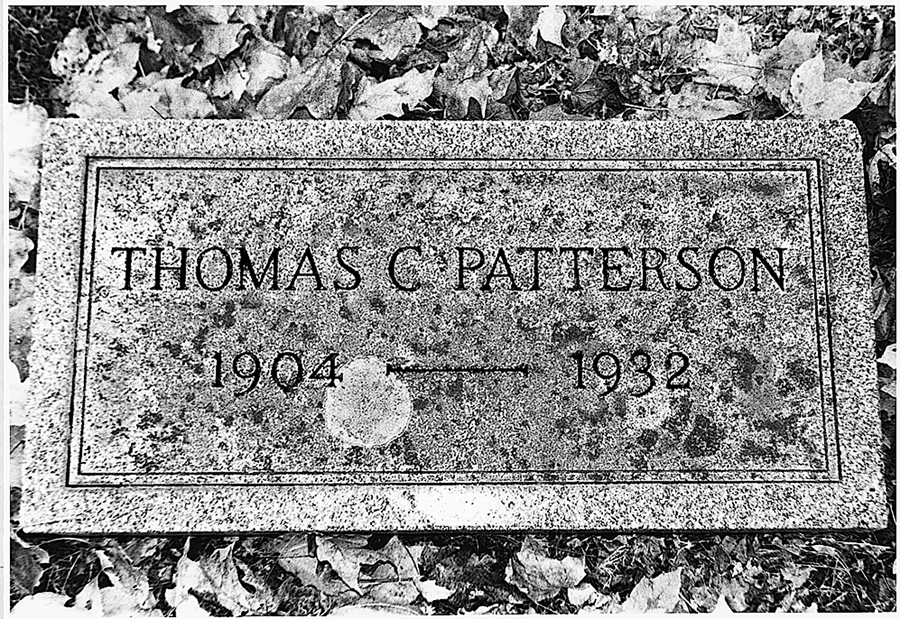

The Staunton Road Murder-Suicide

On Oct. 25, 1932, Huntington residents awoke to read front-page headlines about the murders of coal executive S.W. Patterson and his wife Mary at the hands of their 27-year-old son, Thomas C. Patterson, who then took his own life. The tragic ending of this prominent Huntington family occurred in the palatial Patterson residence on Staunton Road. Evidence at the scene of the double murder-suicide showed that Mrs. Patterson had been shot twice in the head as she listened to a radio program in the living room. Mr. Patterson was killed as he sat reading in his study at the other end of the hall. He was shot once in the head and there was a gash in his forehead, presumably from the blow of a hatchet that was later found in his son’s room.

After the murders of his parents, the son, Thomas, locked himself in his bedroom where he slashed his wrists with a large butcher knife and bled to death. An article reported that a note found in his bathroom read: “I have been murdered by a ghost — a devil. I wish to be cremated. Homicidal maniac. I’m sorry.” The article stated the note “was signed by the young man’s initials — T.C.P.” The bathroom was described as “a shambles,” with blood-smeared walls where the younger Patterson had tried to write on the walls with his own blood.

A news article stated that Thomas Patterson was “a writer and poet” who had graduated from Yale University in 1926. After his graduation, Patterson had pursued a literary career.

The official investigation revealed that the younger Patterson had been suffering from a mental condition for several years and had been under the care of a Baltimore psychiatrist who had recommended that he be institutionalized.

The Unsolved Murder Mystery

On Oct. 17, 1936, Huntington was rocked by news of the murder of one of the city’s most socially prominent women in her home on “Millionaires’ Row.” Juliette B. Enslow, age 63, the wealthy widow of notable Huntington businessman Frank Bliss Enslow, was found dead in her bedroom on the second floor of the Enslow mansion at 1307 Third Ave. With 27 rooms, marble fireplaces, Tiffany chandeliers and stained-glass windows, the Enslow home was a center of Huntington social life in the early 1900s. Parties frequently were given in the mansion for the city’s affluent citizens.

At some point between 2 and 4 a.m., Mrs. Enslow was “stabbed in the head with a finely pointed instrument, beat about the face and body and possibly strangled with a towel found loosely knotted about her throat,” stated a newspaper account. An investigation showed that valuable diamond rings were missing.

In addition to the wealthy widow, the mansion was occupied by her son, Charles Baldwin, and Lizzie E. Bricker, her housekeeper and companion. There also was a staff of servants.

Police soon ruled out burglary as the motive and worked on the assumption that it had been an “inside job.” Ten days after her murder, Enslow’s son Charles was arraigned on a charge of homicide. After a jury trial in common pleas court, he was found not guilty. Three years later, a new development in the case was reported by The Herald-Dispatch: the discovery of one of the two valuable diamond rings in a “catch basin” in the alley behind the Enslow home. Despite the discovery of the missing gem, there is no indication that this baffling case was reopened by the police. More than 86 years later, mystery still surrounds the brutal bedroom murder.

The 1937 Flood Devastates Huntington

Like other Ohio River communities, early Huntington was regularly visited by damaging floods. Every few years, the Ohio would surge out of its banks and inundate the growing town. When the water receded, folks would clean up the mess and get back to work. The 1913 flood was the worst ever — until 1937.

January of that year was unusually warm. Winter’s rapidly melting snow cover combined with 19 straight days of heavy rain to create just the right conditions for an historic Ohio River flood that inundated thousands of homes, businesses, factories and farms in a half-dozen states.

At 11 a.m. on Jan. 27, 1937, the Ohio reached a depth of 69.45 feet at Huntington. That was more than 19 feet above the official flood stage and 3 feet higher than the 1913 flood. The raging water flooded most of the city’s downtown and drove thousands of residents from their homes. People in rowboats made their way along downtown’s Fourth Avenue. Relief centers, set up in undamaged churches and schools, struggled to feed as many as 9,000 people a day. When the river receded, five people were dead and the city was a soggy ruin.

Could a new flood as damaging as 1937’s strike the Ohio Valley again? Experts say that’s highly unlikely but not impossible. If that happened, however, Huntington would be safe and dry behind the massive floodwall that has protected it for 80 years.

The Huntington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which built the floodwall, estimates that since its completion in 1943 the wall has prevented more than $250 million in flood damages to Huntington homes and businesses.

A State Hospital Fire Claims 17 Lives

It was Thanksgiving Eve in 1952. Most of the community was in a festive mood, already relaxing and looking forward to the next day’s holiday.

Then, shortly after 7 p.m., the bells started ringing at the Huntington Fire Department’s old Alarm Headquarters on Ninth Street. The automated alarm system indicated a fire at the Huntington State Hospital on Norway Avenue. No one knew it in those first hectic minutes, but the alarm triggered what would be one of the most horrific chapters in the city’s history.

The death toll in the fire at the State Hospital remains Huntington’s worst ever. Fourteen women and girls died that night. Three more patients died from their injuries in the following days.

Firefighters who raced to the scene found an old brick ward building in flames. A fire had erupted in the basement boiler room and quickly spread. Women and children housed in the three-story structure frantically screamed for help as firefighters used hammers, chisels and anything else they could find to batter away at the building’s heavy wire-mesh window screens.

Fortunately, 40 children were rescued from the burning building. Some had been tied to their beds, and firefighters had to untie them before carrying them to safety.

Ironically, a new building was under construction on the night of the fatal fire, and a hospital official told reporters the patients in the building that burned were scheduled to be transferred to the new building within a few weeks.

Marshall Becomes a University

Take a determined college president and an enthusiastic group of supporters, add a bit of political wheeling and dealing, and what’s the result? A piece of state legislation that transformed Marshall College into Marshall University and dramatically altered the school’s future.

In a sense, Marshall’s history can be divided into two parts — everything before 1961 and everything since. It was in 1961 that the West Virginia Legislature approved a measure making a reality of Marshall’s long-cherished dream of becoming a university. Moving up to university status laid the foundation for the spectacular growth that has unfolded at MU in the decades since.

That historic victory was a team effort. But while the team had many players, it had only one coach — President Stewart H. Smith, who literally worked night and day to win over reluctant state lawmakers and convince them that Marshall merited the elevated status it was seeking.

In 1960, the state Board of Education, acting on a request from Smith, recommended that the Legislature designate Marshall a university. That touched off a battle royale between Marshall’s backers and supporters of West Virginia University, who were determined to preserve its status as the state’s only university. The progress of the necessary legislation through the Legislature was an up-and-down proposition, but ultimately the bill was successful.

When news of the Legislature’s final approval of the Marshall bill reached Huntington, it set off a series of impromptu campus celebrations which saw students shouting with glee and waving copies of an EXTRA! that was published by The Parthenon, the campus newspaper. The newspaper’s huge headline: “We are now Marshall U.”

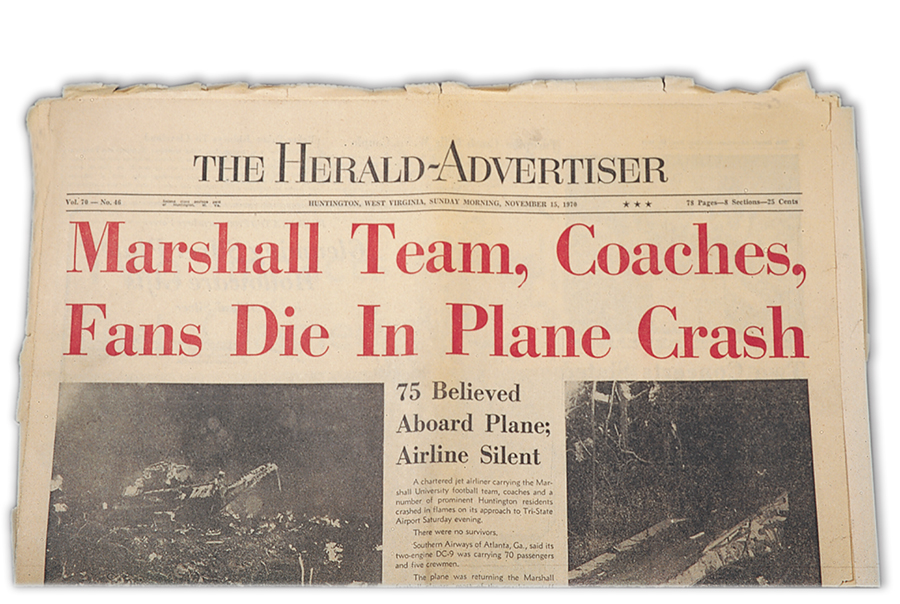

The Marshall Plane Crash

On Nov. 14, 1970, a chartered jet airliner carrying most of the Marshall University football team crashed into a hillside while approaching Huntington’s Tri-State Airport. The team was returning from that day’s game, a 17-14 loss to East Carolina University.

The plane crash claimed the lives of all 75 people aboard — 37 members of the football team, their coaches, the plane’s crew members and two dozen prominent community members who had traveled to North Carolina to cheer on the Thundering Herd. The tragedy deeply shook Marshall and Huntington. Decades later, the emotional wounds from the tragedy remain. Some scars never heal.

More than 7,000 mourners attended a memorial service at the Veterans Memorial Field House on the evening after the crash. Six players whose bodies could not be individually identified were buried at Spring Hill Cemetery.

In the wake of the disaster, a new student union, then under construction, was completed and named the Memorial Student Center. Adjacent to the center stands a 13-foot-tall bronze and copper fountain. Its 150 welded pipes reach toward the sky, while water sprays upward from the center and pours down into a pool.

Noted sculptor Harry Bertoia said his intent in designing the piece was to “commemorate the living, rather than death, on the waters of life, rising, receding and surging so as to express upward growth, immortality and eternity.”

Each year on November 14 a memorial ceremony is held at the fountain to commemorate the never-to-be-forgotten plane crash.

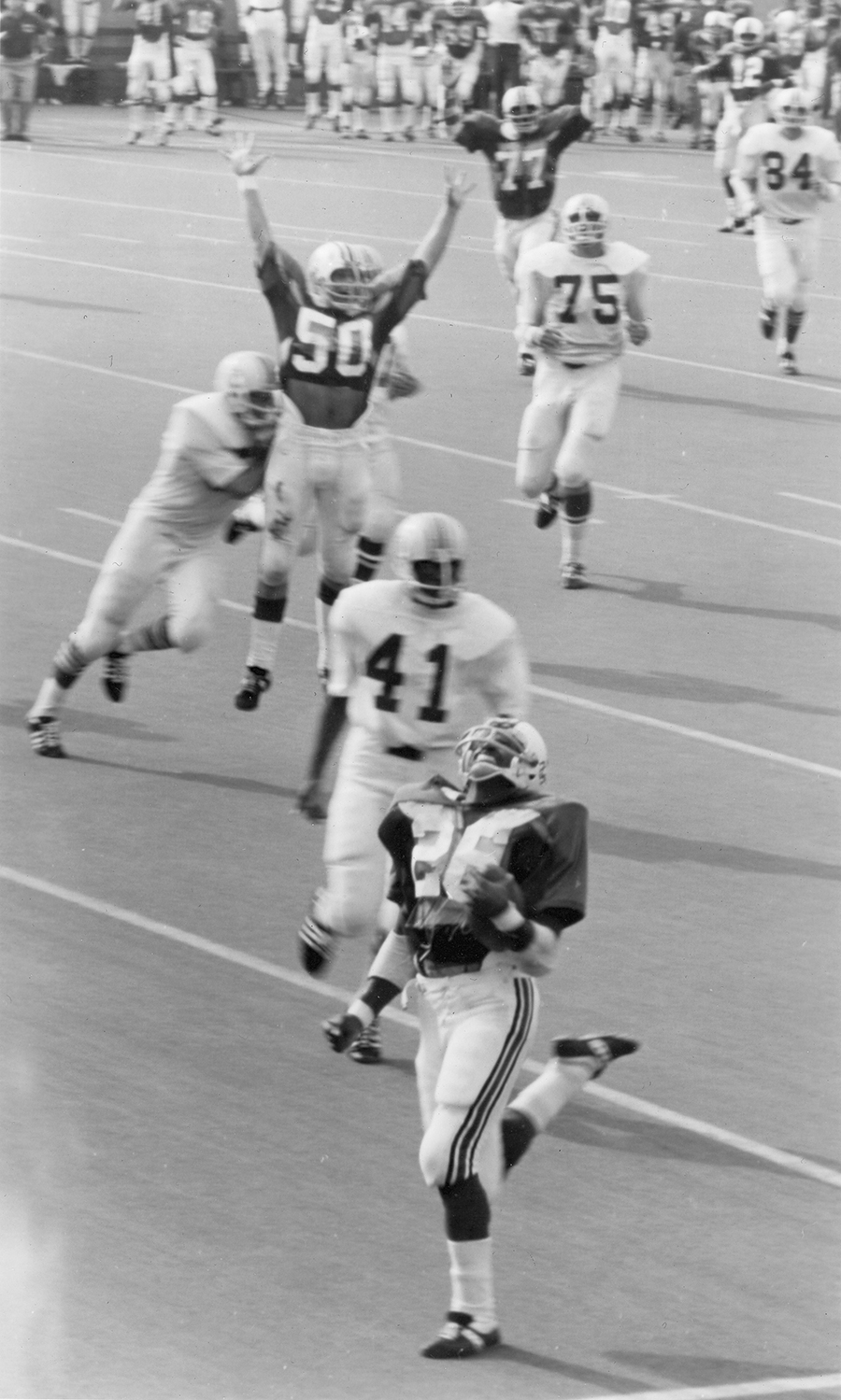

Young Thundering Herd Upsets Xavier

Following the Marshall plane crash tragedy, many wondered if the university would ever field a football team again. However, school officials, inspired by the students’ desire to see the program rise from the ashes, opted to forge ahead for the 1971 season. The task wouldn’t be easy: at the time, the NCAA prohibited freshmen from playing varsity sports. Marshall successfully lobbied the NCAA for a special exemption and began recruiting a team made up almost entirely of 18-year-olds.

Not much was expected from the “Young Thundering Herd,” as they were called, in 1971. However, in their first home game since the plane crash just 11 months earlier, the team upset heavily favored Xavier 15-13 with a touchdown pass from Reggie Oliver to Terry Gardner as time literally expired on the game clock. Fans stormed the field and celebrated well after the game ended. The shocking Sept. 25, 1971, win is now considered the greatest victory in school history and the subject of the 2007 movie We Are Marshall.

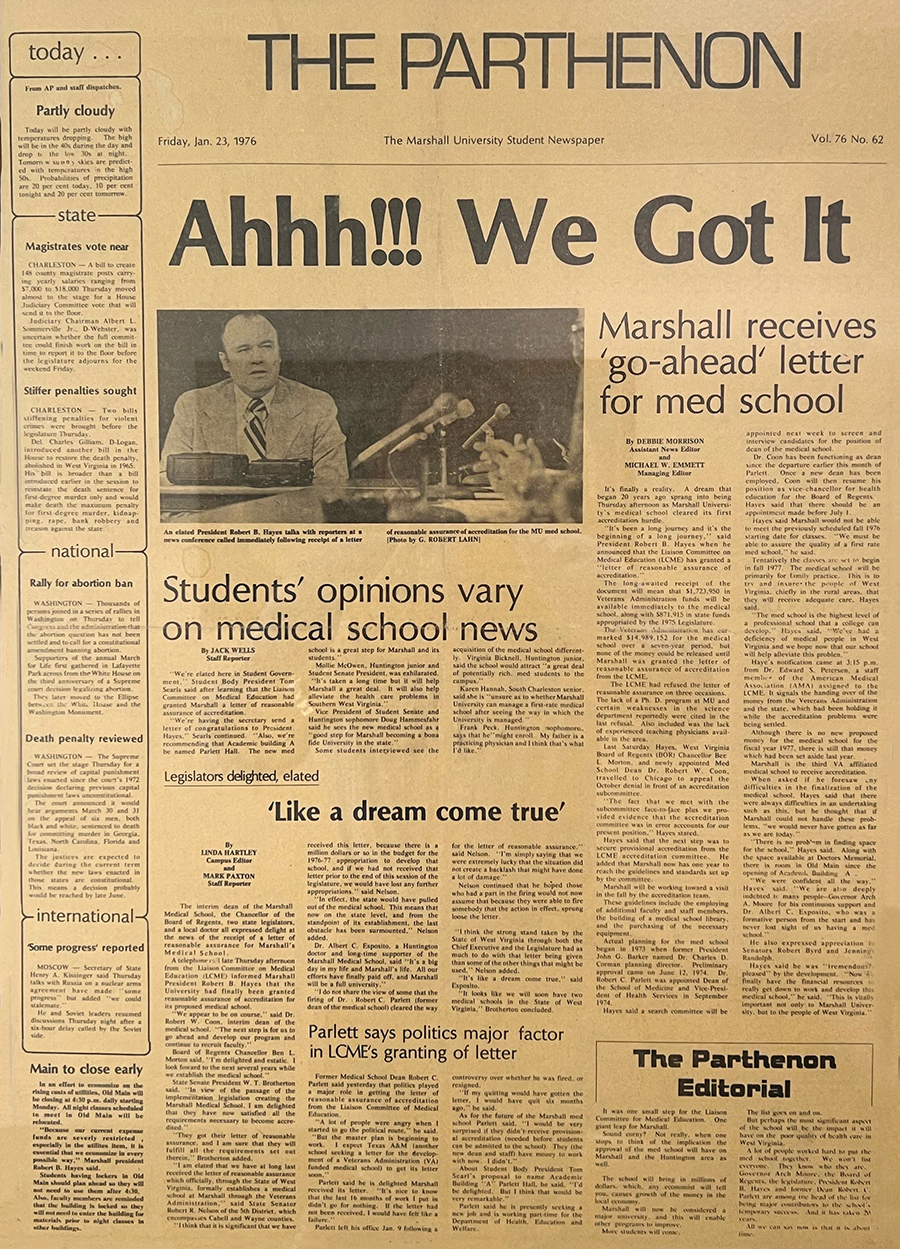

The Med School Dream Comes True

Despite stubborn opposition from Morgantown and Charleston, the longtime dream of a Marshall medical school became a reality in the 1970s. Supporters of the medical school at West Virginia University insisted WVU should remain the state’s only med school. Meanwhile, political and business leaders in Charleston argued that if there was to be a second med school, it should be located there, not at Marshall.

Dr. Albert C. Esposito (1912-1995), an ophthalmologist, practiced in Huntington for 48 years, from 1946 until he retired in 1994. Today, he is widely looked on as the “Father of the Marshall School of Medicine.” He served two terms in the West Virginia House of Delegates, where he repeatedly voiced his support for a med school at Marshall. When Dr. Robert C. Hayes became Marshall’s president in 1974, he and Esposito worked hand in hand to make that dream a reality.

The federal government provided $16 million in startup funding for the school, which in 1978 admitted its first class of 20 men and women. Generous contributions from the private sector supplemented the federal funding. The school’s early donors included Ashland Oil, the Gannett Foundation, the Benedum Foundation and Huntington Alloys.

The late Joan C. Edwards was an especially generous benefactor to the school and so it was named in her honor. Today, the Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine specializes in rural health issues as it strives to recruit students from rural West Virginia and place graduates in clinical practice in the state’s rural areas.