Just who is John Drinko and why is the West Virginia native and Marshall alumnus so interested in his alma mater?

By John H. Houvouras

HQ 10 | WINTER 1992

The story of John Deaver Drinko is one that, most likely, you have never heard. It is a story of one of Marshall University’s most accomplished alumnus and his rise to the top of his profession.

He comes from a distinguished lineage of attorneys in a historic law practice … men like Newton D. Baker (1871- 1937), who Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes called, “the outstanding lawyer of his generation;” and Drinko’s mentor, Joseph C. Hostetler (1886-1958), both giants in their day. When you enter the prestigious law offices of Baker & Hostetler in downtown Cleveland, Ohio, three portraits hang on the wall: Newton Baker’s, Joseph Hostetler’s and John Drinko’s. No others. Just these three.

He is a man who, upon his ascent to power at Baker & Hostetler in the 1960s and ’70s, nearly singlehandedly took a practice with 64 attorneys in one office and built it into the nation’s 16th largest law firm, now with more than 500 attorneys in eight cities across the United States. Their clients include, among numerous others, CBS Television, Major League Baseball, Time Warner Inc., Scripps Howard and Elvis Presley Enterprises Inc.

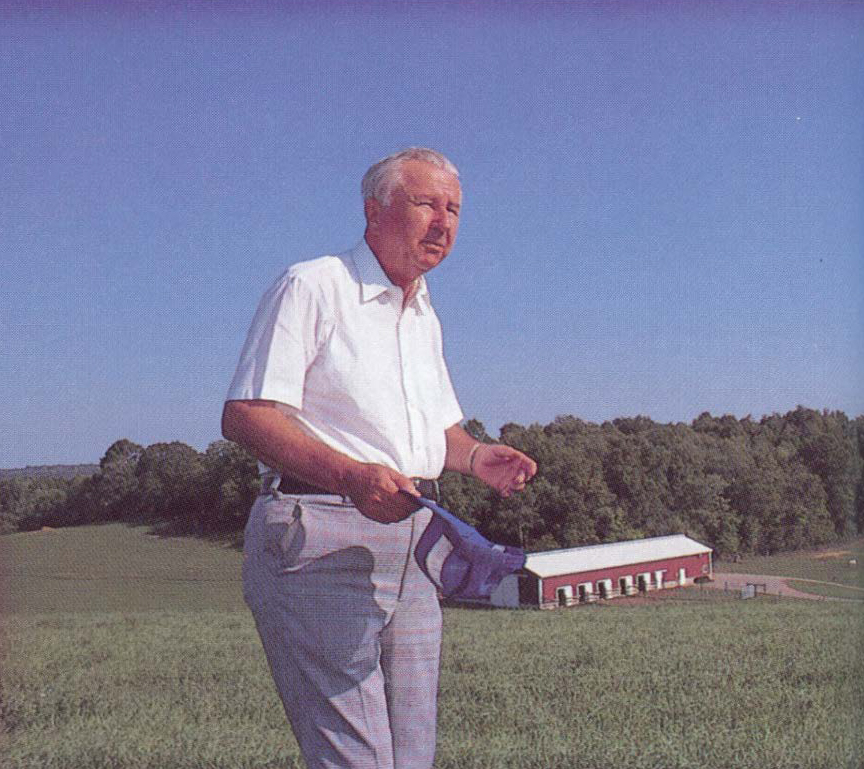

But Drinko is more than a brilliant attorney. He is a farmer, family man, philanthropist, world traveler, entrepreneur, and student of life. But perhaps most importantly to John Drinko, he is a graduate of Marshall College and a native West Virginian.

He has come a long way from his humble beginnings in St. Mary’s, W.Va., where town meetings were held to discuss the possibility of changing his Hungarian name at an early age. Apparently, the folks in St. Mary’s thought the young man might have a better chance of making it in the world with a less ethnic-sounding name like Smith or Jones. But young Drinko would have none of it. He told them all to go to hell.

Today an accomplished multimillionaire, Drinko continues to take pride in his name, his alma mater and his past. When asked to fund the first academic chair at Marshall University in 1981, Drinko reached for his wallet and wrote a check for a cool $1 million. But it isn’t his money or power that most impresses. Instead, it is a number of distinctive characteristics, all complex, that answer the puzzling question: Just who is John Drinko?

• • •

He was born and raised in St. Mary’s, W.Va., a community of 2,500 people, during the Great Depression. Rumor has it that by the age of 5, he already was reading Latin and Shakespeare. A self-proclaimed born speed reader, he professes to have read Gone With The Wind for the first time in one afternoon. And although these claims may not seem plausible, if you ask anyone who knows Drinko, they will tell you that there’s no reason to doubt his word. According to his peers, he is a genius.

“His mind has such depth and perception,” notes Paul White, a partner at Baker & Hostetler. “He has an intellectual capacity that cannot be measured.”

His father walked out on him and his mother when he was just a boy – a subject Drinko refuses to discuss. This made financial matters even worse for the two and it cast the youngster into the role of man of the house very early in life. Despite the fact that there was poverty everywhere, young Drinko always found a way to hustle a buck. He sold anything he could get his hands on, including blackberries, peaches, shirts, socks and his favorite, real silk hosiery.

“I got to measure women’s legs,” says Drinko. “It wasn’t all bad.” By the age of 12, he was driving a truck. But there were good times as well. As Drinko says, “The most wonderful part of your life is when you don’t have a damn thing. What do you have to lose?”

In school, he was advanced to higher classes because of his gifted abilities. “I was a precocious little S.O.B.,” Drinko recalls. Legend confirms that indeed he was. When his mother remarried to a man who Drinko deemed unsuitable, the teenager took it upon himself to throw him out of the house.

In high school, he excelled not only in the classroom but on the playing field as well. He was regarded as an excellent football and basketball player. Still making money to help support his mother and half sister Frances, he hustled pool, fought barefisted for money at carnivals and wrestled bears. As Drinko contends, “I never lost.”

When it came time to graduate from high school, Drinko learned that the majority of his class was unable to afford class rings. And with that, he formed a committee and set out to raise enough money to purchase the rings by selling hot dogs, popcorn or whatever it took. “Nobody in my class is going to graduate from high school without a class ring,” he asserted. And not a single one did.

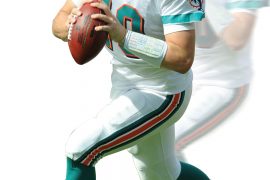

Upon graduation from high school, Drinko left home and arrived on campus at then Marshall College wearing a burlap shirt that his mother had made. He immediately went to work at a local A&P grocery store and continued what would be a lifelong responsibility of sending money home to his mother and Frances. He played football for the Thundering Herd and later basketball for the legendary Cam Henderson. Those who remember his play recall that on the court he was a classic “take-out” artist. During one game, Drinko fouled an opponent pretty good – good enough in fact that the player had to be helped off the court. As Drinko returned to the bench, angry fans shouted at him along the way, but when he passed Cam Henderson, the old man said, “That’s the way to go, son.”

In his spare time, Drinko continued to hustle money and, when he could, attended dances at the old Vanity Fair in downtown Huntington. In those days, the whites danced upstairs on the balcony and the Blacks danced downstairs. Rumor has it that Drinko was one of the first in town to break the racial barrier when he went downstairs and asked a young black girl to dance. “I never was concerned with the color of someone’s skin,” says Drinko. “I was pretty good on my feet and I wanted to go a round with the best dancer in town. As it turned out, the best dancer at the time was Black. Obviously that wasn’t going to stop me.”

In the classroom, Drinko grew to become friends with his professors. Most likely, there was mutual respect. “Looking back,” says Drinko, “I had some of the greatest teachers in the world.”

Drinko graduated from Marshall in 1941 with honors and was offered scholarships to such schools as Harvard and Yale but he opted to stay in the area. He was still concerned about his mother and half-sister.

“I knew how to make money in this part of the country and I had an obligation to provide for my family.”

Drinko enrolled at Ohio State Law School, and because of his speed-reading ability, breezed through his homework. That left his evenings open. He joined a poker club and quickly learned the art of gambling. It was, in his own words, one of the better lessons in life.

“I don’t gamble,” Drinko insists. “I only put my money on sure things.” Those familiar with his business dealings agree. They describe his judgment in money matters as phenomenal and innovative – one of the many reasons for the wealth he has amassed over the years.

At Ohio State, he went on to finish at the top of his class and upon graduation, accepted a fellowship at a law firm in Houston, Texas. Early into the fellowship, the firm sent the greenhorn Drinko on an errand to see its top client – the ornery millionaire Jesse Jones who, according to Drinko, owned nearly all of Houston. Young Drinko was greeted by Jones with a barrage of insults and profanity obviously intended to test the young man’s character. After Drinko had heard enough, he told Jones to “go to hell,” and stormed out of the office. By the time he made it back to the law firm, Jones had already called ahead and instructed the senior partner to “Hire that kid!”

However, Drinko chose to return to Ohio so he could look after his family. Joseph Hostetler of Baker & Hostetler notoriety in Cleveland hired Drinko in 1945 and took an immediate liking to the young man. And although he had to compete with what he called the “Harvard and Yale fancy boys from the country clubs,” Drinko rose to the top of the firm. He concentrated his talents on corporate and business law, including financing, mergers and acquisitions, planning and sales. Hostetler soon came to revere Drinko as his most trusted colleague and, in time, groomed the West Virginia native and Marshall College graduate as his successor.

• • •

As John Drinko arrived at work early one morning in 1945, a young lady who also worked in the office building noticed him walking through the lobby. Her name was Libby Gibson.

“When I saw this young man, I felt kind of funny,” she remembers. “I already had a boyfriend in the service, and I thought to myself, ‘You shouldn’t be feeling this way.”‘

Libby worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company as a bookkeeper, and one of the perks at the company was receiving free tickets to various social events throughout the city. As fate would have it, her roommate worked in Drinko’s office and Libby often found herself at Baker & Hostetler handing out some of the extra tickets she was unable to use. One afternoon, Drinko asked to meet the young lady who was giving all the tickets away.

“When I first met him I didn’t like his attitude,” recalls Libby. “He was too self-assured and aloof. He also mentioned that he didn’t believe lawyers should date the secretaries that worked in the building, even though he knew I wasn’t a secretary.”

However, Libby’s roommate later arranged a date between the two and a platonic friendship was born. The couple often went out but a romantic spark was never ignited. Early on, Drinko informed Libby that he had no intentions of getting serious as he had a mother and halfsister to take care of. In time, however, things would change.

“Little by little,” Libby remembers, “the web kept tightening and it wasn’t long before we were both caught.”

“I married way above myself,” Drinko recalled years later. Gibson was from a fine family in Pennsylvania – not bad for a good ol’ boy from West Virginia.

• • •

In the years that followed his marriage, Drinko pressed on in his work as the premier young attorney at Baker & Hostetler. His seven-day work week, according to his wife, began at 7 a.m. and ended at midnight. He took breaks only in the evenings to have dinner in town with his new bride. But once he had his first child, Libby convinced him to take Sundays off.

In addition to his law practice, Drinko founded the Cleveland Institute of Electronics in his spare time. What began as a small mail-order school would later grow into a profitable venture that would ultimately add to his fortune.

In 1968, the management committee at Baker & Hostetler appointed John Drinko chairman of a subcommittee to study how to strengthen the management and internal procedures of the firm. His recommendations were quickly adopted and, in 1969, he was elected to the management committee where he quickly became the dominant force. He was then elected managing partner of the firm and soon thereafter, seized an opportunity that would set in motion a period of unprecedented growth in the firm’s history. In the early 1970s, Drinko completed the first merger of a local law firm. It would be the beginning of his visionary plan to make Baker & Hostetler one of the first national law firms.

Today, because of Drinko’s foresight, Baker & Hostetler has offices in Cleveland, Columbus, Washington, Denver, Los Angeles, Long Beach, Houston and Orlando. The firm has grown from 64 attorneys in the Cleveland office to 500 attorneys and 1,100 support staff in eight cities. It is the nation’s 16th largest law firm.

Perhaps a great determinant of Drinko’s success, combined with his obvious intellectual capacity, is his innate curiosity. He is the kind of man who takes a sincere interest in virtually every subject he encounters. Whether it is business, politics, science, or the arts, John Drinko is determined to learn as much about a given subject as he can. By 6:30 a.m. each day, he has read every major newspaper in America and by nightfall, he has finished yet another book.

“He is a practicing scholar,” notes Dr. Ned Boehm, vice president for institutional advancement at Marshall University. “I’ve met people who were brilliant in certain arenas, but John is brilliant in all of them.”

• • •

By now, Drinko had four children, two boys and two girls, and while they were all still relatively young, he made the decision that the family would undertake a project to see the United States. And, over the course of a five-year period, during his vacation time, they did just that. The ever-meticulous Drinko broke the country down into sections, and when he had vacation time, the family set out on a new adventure. Whether by railroad or the family station wagon, they blanketed the country and, in subsequent years, made the same journey through Europe.

With those missions completed, Drinko awoke one Sunday morning to find an ad in the newspaper for a 31-foot, 4-bed camper. He told Libby, “Let’s go look at it after church.” By the end of the week, he had purchased the monster vehicle, had it prepped, and was on his way with the family in tow to Alaska.

Deep into the arctic wilderness, the camper broke down at a gas station. It would take hours to fix. The gas station owner, who was married to an Eskimo woman, took an immediate liking to Drinko in the hours that passed. Ever curious, Drinko delved into the gentleman’s interests and background. The two discussed their respective adventures in life and, before the day was done, the man was trying to talk Drinko into leaving his family for a few days to embark upon a trek across a frozen river in a part of North America few white men had ever seen. But Drinko obviously declined. Months later, he received a telegram at his office from the man in Alaska.

“The river is frozen.” Stop. “Now is the perfect time to go.” Stop.

Drinko telegrammed back.

“Can’t.” Stop. “Still married to white woman.” Stop.

• • •

On Nov. 14, 1970, the plane carrying the Marshall University football team crashed upon its descent into Huntington’s Tri-State Airport. All 75 players, coaches, and fans were killed. When John Drinko heard the news, he chartered the first plane out of Cleveland and left for Huntington. He immediately volunteered his time and began fundraising efforts on behalf of the university. He used his contacts to secure nearly $130,000 in contributions and before he returned to Cleveland, had penned a personal check to the university for an undisclosed amount that one university official said was “at least” in the five figure range. It is said that anonymous checks were also mailed to the university on a regular basis for several months following the disaster. Officials believe they were from Drinko.

“What is remarkable about John is that his generosity is beyond belief,” notes Boehm. “He is compassionate and he truly cares.”

Boehm has come to know Drinko well in recent years in his role as Drinko’ s friend and contact in Huntington.

“What is important to John, in my opinion, is his belief in God, his wife, his family, his career, his community, and his past. He has a fierce, intense loyalty to his past and has never forgotten any one person along the way.

“When John was just a boy, his mother taught him that it was important to say thank you and express the proper gratitude to those who have helped you in life. And I think that sums up his life. John has spent his entire life saying thank you. What drives him to give is not a desire for recognition, but, instead, to do what his mother taught him.”

Yet another example of Drinko’s abilities and dedication to others involved close personal friend and client, Edward J. Mellen. Mellen’s wife was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and suffered with the disease for 35 years before she passed away. Before Mellen himself died years later, he appointed Drinko executor of his large estate and asked him to use the money to help fight the crippling disease.

Drinko in turn set out to find the best doctor in the world to head up the newly formed Mellen Center at the Cleveland Clinic. He found in Dr. John P. Conomy a man who had devoted most of his life to the study of MS and asked him to head the center. Today, that center is a testament to Mellen, Conomy and Drinko.

“If it weren’t for John Drinko, this place wouldn’t be here,” Conomy asserts. “There are 64 centers like this around the world, and this is the best.”

More than 250,000 people in the United States are afflicted with the neurological disease. Conomy and Drinko determined medical treatment isn’t enough. More needs to be done for these people including treating their emotional struggles to cope with the disease, helping them come to terms with their loss of independence, providing financial assistance, and expanding the frontiers of rehabilitation and research. Conomy’s ultimate goal is to eradicate the disease just as polio was in the 1940s.

“If it weren’t for the John Drinkos of the world, we couldn’t take care of these people,” Conomy added.

More recently, Drinko’s concern for his close friend and colleague, Jim Chapman, was demonstrated when Chapman was diagnosed with cancer.

“John had the best doctors he could find calling on me,” recalled Chapman. “He had them checking up on me every day. That’s just the kind of man he is.”

When Drinko learned that a young man from West Virginia was being admitted to the Cleveland Clinic for treatment last year, he walked over to the medical records library, pulled the patient’s file, and wrote on the outside: “Take special care of this young man.” It was simply signed “Drinko.”

• • •

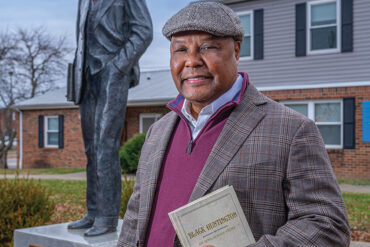

What little recognition John Drinko has received in the Huntington community stems primarily from The Drinko Chair at Marshall University, which he and his wife, Libby, established in the 1980s with a $1 million gift. It was Dr. Bernard Queen at The Marshall University Foundation who came across Drinko’s name while doing some research of graduates who had made it big. Queen’s goal was to establish a series of academic chairs at Marshall and he chose Drinko as his first target.

“I called Mr. Drinko and told him who I was and that I would like to meet with him,” Queen recalls. “He said, ‘Come on up.”‘

Queen and his wife were treated by the Drinkos to a first-class weekend at their farm in Coshocton, Ohio, where he raises prize-winning Charolais cattle. Queen didn’t bring up the subject of money all weekend. However, on Sunday morning, Drinko decided he wanted to drive into town to pick up a newspaper and asked Queen to come along for the ride.

“I remember we were driving along the rural countryside when John turned to me and said, ‘Queen, what do you want?’

“I told him that I needed someone to take the lead and establish a chair at Marshall. He, in turn, said, ‘How much will you need?’ I looked up at him and said, ‘Just for openers, we’re going to need $250,000.’

“He didn’t say a word,” Queen recalls, “and drove on for about five minutes. Then, he turned to me and said, ‘I don’t see any reason why we can’t do that. Libby and I will take care of it.’”

The additional $750,000 soon followed in lump contributions. It was the single largest private contribution in the history of the university. Drinko understood that the chair needed to be properly funded, and to this day he continues to take an active role in the selection and operation of the chair named in his honor. As Queen points out, Drinko was the pioneering force that started the academic chairs at Marshall University.

“John Drinko is the kind of man who, when he sees a need, is there,” says Queen. “The Marshall plane crash tragedy is a perfect example. He’s the kindest, most unique and I guess the most brilliant man I’ve ever met.”

• • •

If ever there was an advocate for the power of education, it would have to be John Drinko. He is not only a living example of that fact, but a zealous supporter of the growing movement as well. In addition to his chair at Marshall University, Drinko has been the driving force behind establishing six professionals chairs at four Ohio law schools as well as the Baker & Hostetler Law Library and Building Fund at The Ohio State College of Law. Finally, he established a scholarship at Marshall University for graduates of St. Mary’s High School in St. Mary’s, W.Va. One scholar is selected each year and receives a full scholarship and all the benefits that come with being associated with the Drinko name. As Boehm points out, it is Drinko’s way of showing the kids the other side of the mountain.

“He truly believes that you can better the world through education,” notes wife Libby. “He truly does.”

• • •

When John Drinko proposed to Libby Gibson in the late 1940s, he said to her, “I don’t know if I’ll ever amount to anything. I don’t know if I’ll be rich or poor. But I can promise you one thing: There will never be a dull moment.” Today, with their four children grown, the two have traveled the world visiting nearly every continent on the globe. “Sometimes,” says Libby, “I pray for a dull moment.”

Some years ago, Drinko made the trip back to St. Mary’s to see his home and tend to his family’s graves. Even today, he still feels that responsibility to his family, especially to his now-deceased mother, and pays a local man to maintain the family cemetery plots.

While in St. Mary’s that day, Drinko made his way to the street corner to say hello to some of the locals. In St. Mary’s, the men who sit around the street corner are considered to be the town sages, a Who’s Who Committee of sorts, and Drinko made a point of stopping by to let them look him over.

“So, Deaver,” one of the old-timers said while chewing on a wad of tobacco, “are ya doin’ well?” Drinko went on to tell them that he was an attorney in Cleveland and was doing fine.

“Ya in any big clubs up there?” one of the men asked. Drinko replied that he had just been accepted into the prestigious Union Club.

“What’s the matter, Deaver?” another man griped. “Can’t you afford the Elks?”

• • •

John Drinko is a man undeniably linked to his past and keenly poised for the future. Perhaps his greatest gift to Marshall University is not the money he has generously contributed over the years, but instead, his undying loyalty to his roots. When a prominent Ohio politician recently joked that the only good thing to come out of West Virginia was an empty bus, Drinko phoned the politician and informed him that he was terminating all future funding to the man’s political party. And to this day, Drinko’s contributions, considered to have been quite substantial, have been withheld.

In 1983, Dr. Bernard Queen nominated Drinko to receive an honorary doctorate at Marshall University. ThenPresident Bob Hayes and the university committee readily agreed. Queen then asked the Drinkos to dinner in Huntington at a local restaurant, and after the meal, handed the Marshall alumnus a letter indicating that he had been selected to receive the award. As Drinko looked over the letter, a tear ran down his face.

• • •

The story of John Deaver Drinko is one that, most likely, you will never forget. His rise to the top is a testament not only to the man, but to his heritage as well. For perhaps there is no better example of what this state and Marshall University can produce than the fiercely proud attorney from St. Mary’s, W.Va.