By Benita Heath

HQ 41 | WINTER/SPRING 2001

The early morning sun was rising as John Hankins focused his formidable knowledge on a pretty mundane item: light bulbs. Or rather the lack thereof and how the architects of a bygone era had resolved this quandary, quite cleverly in his estimation. The lawyer who has dazzled Huntington with his extensive restoration projects knows inventiveness when he sees it.

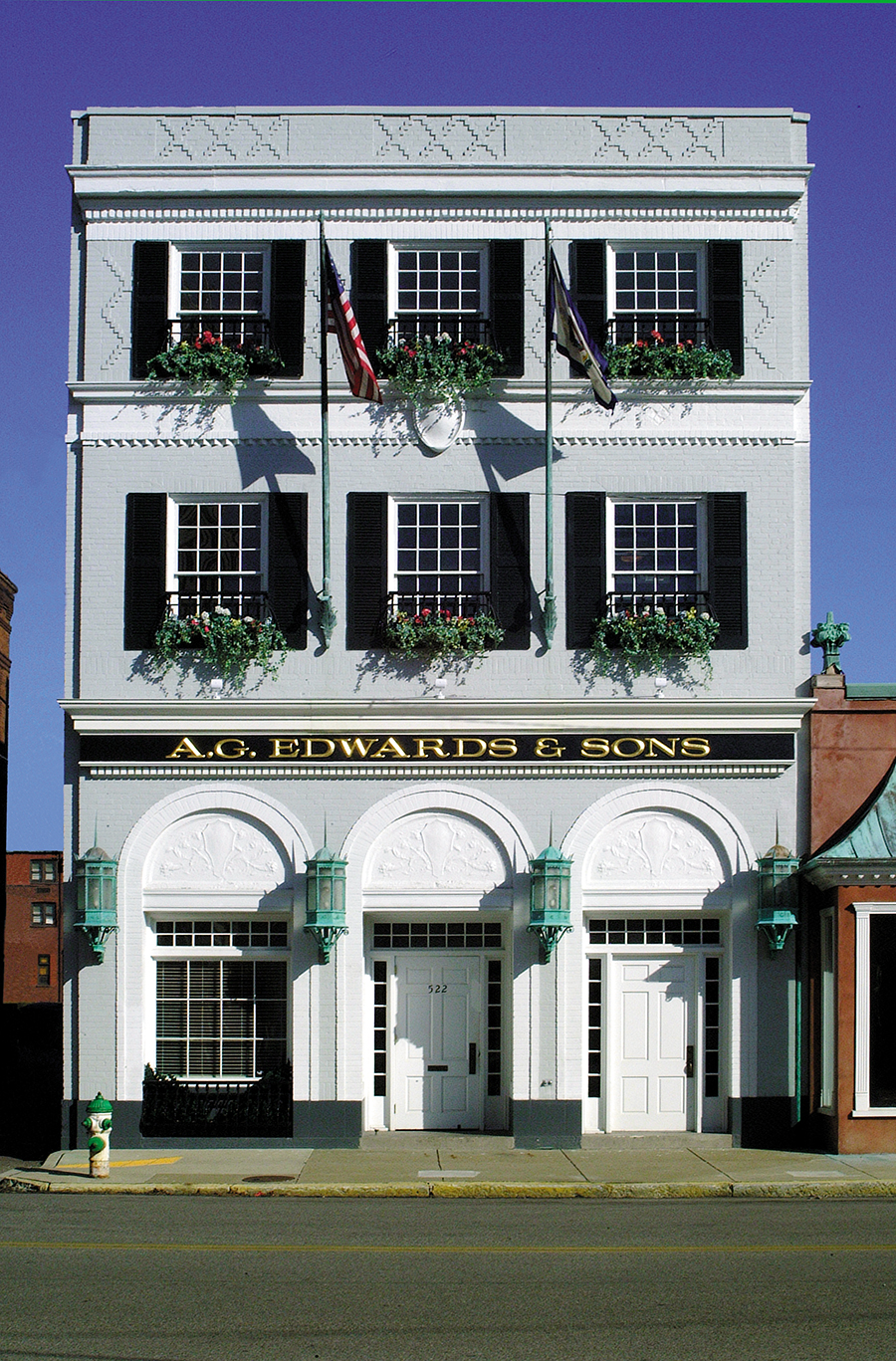

Hankins was standing in the conference room of the A.G. Edwards firm, located in the former Huntington Chamber of Commerce building, on Ninth Street, just across from another Hankins restoration project … the Guaranty Bank and Trust Co. The slightly rectangular room, about the size of dining room in one of the mansions along Ritter Park, features two intricate windows, atypical in design for an office, but quite practical as Hankins was expertly explaining that day.

The windows resemble a Byzantine triptych in shape with a collection of smaller transom windows above in a double-decker design providing a vital office benefit.

“In 1920 they didn’t have good lighting. Just a light bulb hanging down, so light was very important,” explained Hankins as he reached up to shutter the larger windows.

“You see light could come through the transom window and they could still have privacy.”

As he finished his lecture, he seemed rather pleased with this example of Roaring 20s ingenuity. Perhaps he saw a kindred spirit. After all, ingenuity has been the guiding force in Hankins’ numerous projects.

Continuing the informal tour of his latest project, Hankins moved on to the lobby where he pointed to three arched windows that seemed to stretch up the north wall almost to the sky.

“Two of these had been covered up when we started work,” he said.

But not any more. Hankins had the drywall ripped off. Now all three windows vault to the heavens bringing in sunlight just the way the building’s architects, Meanor and Handloser, had intended when that prominent Huntington firm designed the building in the early 1920s.

The Jackson City Building and Loan commissioned the structure in the glory days of post-World War I Huntington. But quiz longtime Huntingtonians and no one can recall just what the Jackson Loan was. The clue for most people is that building was home to the Chamber of Commerce.

A check in court records shows Jackson owned the building from 1921 to 1934, when Huntington Realty Co. took over. Then in 1946, the Huntington Regional Chamber of Commerce bought the building which it occupied until 1997. That year it was bought by Phoenix Park, Hankins’ holding company that does building restorations.

By whatever name the building was called, Hankins liked what he saw.

“The exterior had a fabulous look. I call it New Orleans French Quarter style,” he said. “And the interior had literally 20-foot high ceilings. And the big banking room had marble but had been modified by someone.

“It was a very poor adaptation of the space and made about half the space unusable.”

Maybe this building didn’t sound like the typical fix up. But a daunting prospect? Never. It was the kind of challenge Hankins obviously relished as he set his work crews to the task.

Originally, the building featured a lobby that stretched to the ceiling. Impressive, but not practical for today.

“We designed a mezzanine treatment for that space that is pretty neat,” he said. “We tripled the amount of space by adding that mezzanine and by taking in the basement. It was a typical dingy, dirty, terrible-looking basement. We converted it to a pretty highly desirable space, incorporating a lot of architectural antiques and a lot of handwork that our woodworking staff built.”

If the railings going up the back wall seem reminiscent, they are. To create the staircase up to the mezzanine, Hankins reached into his treasure trove of warehouses where he stashes his historic finds.

“I call these Richmond, Va., Neoclassical,” he said with a grin when asked about the architectural style of the carved wood balusters, which at one time graced the front porches of houses circa 1900 in that James River city.

Hankins approached the interior of the one-time bank with the touch of an artist respectful of the past. He kept or enhanced the Classical Greek features throughout. Column supports with capitals and plaster supports or brackets shaped in the acanthus leaf catch the eye immediately upon entering the lobby as does the tobacco leaf molding, a common motif in Southern architecture.

However, Hankins took his cue for the interior from the mood of the building’s exterior design and chose to paint the inside in white and Indian ivory.

“That’s in keeping with New Orleans,” he said. “The way it looked with the wonderful huge arched windows, we elected to go with the light paint. When you go in, you see how bright, airy and light it looks.”

The creamy walls reminiscent of a cup of cafe au lait make an agreeable contrast to the massive bronze chandeliers suspended from the lobby ceiling. Light shimmers through tum of the century opalescent glass bowls accented with red stained glass.

Throughout the building, including the newly remodeled basement, are 1870s tin ceilings that Hankins put in as part of his own personal touches.

“This is our version of recessed tin ceilings,” he said.

And a part of the Hankins’ touch is that the ceilings, rough and mottled in texture, look as if they could use a good scraping. The impression is deliberate. “I want the age to show so we just painted over it,” he said.

But while connoisseurs delight in things old, antiquities can be a drawback to a working business so Hankins ripped out the original coal furnace turning that basement space into a home for a modern-day computer.

“We had to take out the furnace with sledge hammers and cut it into pieces,” he said. “We take a building back to a shell and replace everything.”

Lighting treatments appear in a variety of styles in this restoration. A delicate bronze ceiling fixture in the vestibule is original to the building while a small bronze chandelier was added. Hankins found the piece in the dining room of a 1915 home on 27th Street and Third Avenue just before it was torn down.

But among Hankins’ greatest delights are the four verdigris bronze lanterns and matching flagpoles that grace the outside.

“I managed to buy these six architectural gems years ago,” Hankins said. “The four bronze classical lanterns came from New York from a tum of the century building as well as the two bronze flagpoles. They came from a picker. A picker goes through the country and searches out stuff like this. He will find a building being tom down and try to buy items as cheaply as he can, then sell with a markup to people like me.”

The end result is a building that is both functional and aesthetically appealing.

“It serves us well. It is pleasing to the eye for our clients. We get really nice comments from them,” says A.G. Edwards Branch Manager Garry McClure.

The restoration has created a building that looks as if it got washed down with buckets from the Fountain of Youth. But its revival has less mysterious origins, coming from a native son’s quest to restore the past glories of his hometown.

• • •

As Hankins continues his Midas touch on the buildings of our region, the Huntington Quarterly will follow along as the Summer Issue features yet another of his many gems.