Marshall’s University’s School of Journalism is regarded as one of the best in the country

By Bill Bellanger

HQ 6 | WINTER 1991

The squeaky swing on the front porch of the little green and white frame house wheezed above the low voices of its occupants. Lover’s tryst? Hardly. But then could it be a conference site for college student and professor? The answer is yes, because “then” was the late 1920s. The little house was the first home of Marshall College’s journalism department, 17th Street and 5th Avenue.

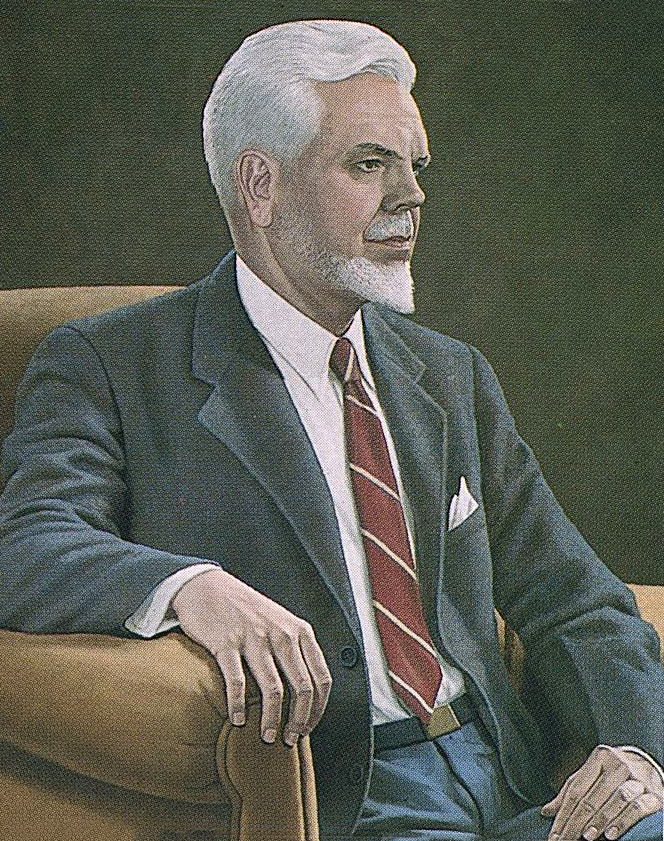

When the swing was squeaking it meant Prof. W. Page Pitt, head of the department, was delivering advice or a scolding to a student, who kept the swing moving to counter nervousness. In that small house the only place for privacy was the swing outdoors on the porch.

Today the little house is long gone. The department has become a school named for the man who established journalism as an academic subject at the college that later became a university.

In that small frame house 60 years ago, the front room served as office with two desks taking up most of the space not occupied by the wooden mantel and a file cabinet.

The mantel of early 1900 decor had a small ray heater, where a burning log should have been. Above it was a bare shelf, used for elbow-leaning. A mirror and overhead an unused shelf completed the decor.

The desks were used by Pitt and Virginia E. Lee, department secretary.

In the adjoining room, a huge circular table, identical to the copy desks of metropolitan newspapers, brought together students and Pitt, who sat at the head seat, or in the “slot” as it was known. Two rows of desks with typewriters filled the rest of the classroom, known as the newsroom. Upstairs an apartment was rented out- the state never lost money on an inch of space.

Pitt’s low roar “heads up!” was the signal he was entering the newsroom, and students better have their assignments ready. In the basic reporting class an assignment was writing an actual news story, not an exercise. Pitt was practical: The college student was required to have a textbook, but students were rarely quizzed on that material.

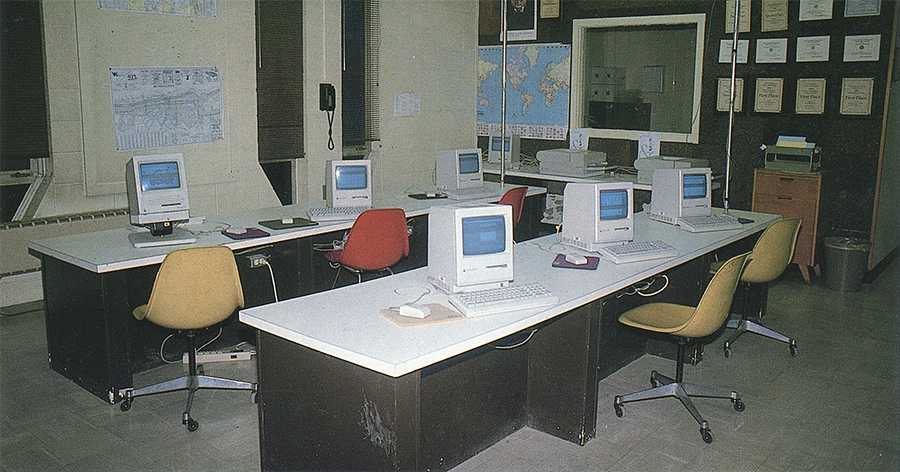

On some days he would dismiss the class with the command “Go out and get a story, then come back and write it!” Students had to work fast – there were never enough typewriters. Even today, Dr. Harold Shaver, director of the school, says technical equipment (for photography, graphics and broadcasting) remains a major need of the school.

Students never knew what to expect from Pitt -no better preparation for newspaper reporting. Until the 1940s, students were prepared only for newspaper work. Classes offered were in basic and advanced reporting, feature writing, editorial writing, book reviewing, copy editing and the history of American journalism.

As more students demanded journalism classes, the department grew. Newspaper editors from The HeraldDispatch became faculty members.

The classes merely reflected the times. There was not much opportunity in the other fields within the profession – radio, advertising, public relations. In any event, newspaper work was considered the best preparation for the field.

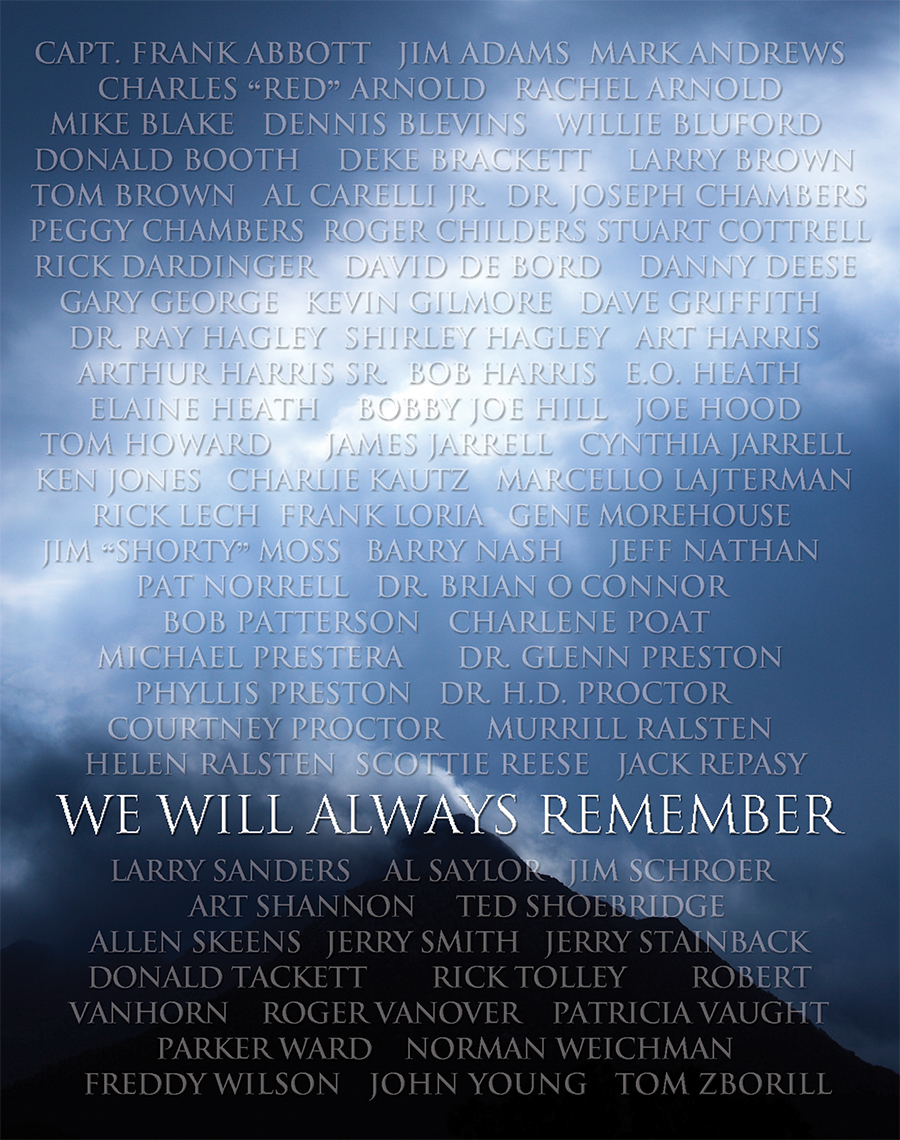

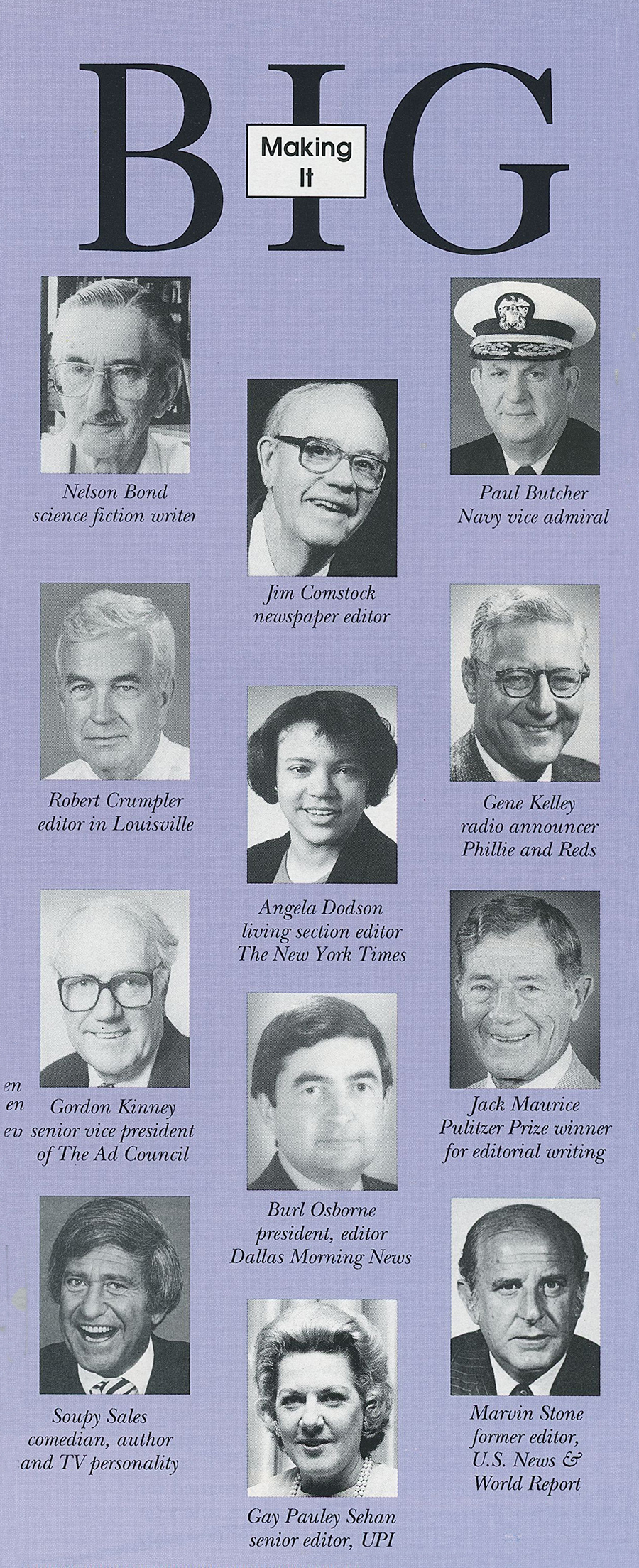

In following years the department, which would eventually become the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism, would produce a variety of nationally known men and women in a variety of fields. Frobusiness executives to Navy admirals – one was a former sports editor, the other newspaper reporter-all the students attribute their success to Pitt’s journalism training. After graduation Paul Butcher was a reporter for The Herald-Dispatch until he entered the Navy and

was assigned to special news writing and public relations. On return visits to Marshall, he never fails to credit the school and The Herald-Dispatch for the training he received. Today on the Wall of Fame in the Marvin Stone Library of the school hang photos of a Pulitzer Prize winner, Jack Maurice, retired editor of the Charleston Daily Mail; foreign correspondent Marvin Stone who covered the world for UPI from Europe to the Orient and the U.S.; Gay Sehan, also for UPI, who covered such events as the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II; Tom Miller, national award-winning investigative reporter; Ernie Salvatore, newspaper and magazine writer specializing in sports; and Jim Comstock, known nationally for his weekly “West Virginia Hillbilly.”

The list widens in subject matter and deepens in number. But all of Pitt’s students en joyed their work in journalism because the “Grand Old Man of Journalism” made them feel it was the most important thing in the world. The list goes on – television general managers and newspaper publishers, anchor men/women, specialized magazine writers, public relations directors and consultants in all fields.

The positions held by the nominees on that Wall of Fame are mute testimony to the changing times and widening of opportunities in fields other than newspapers.

It all began in 1926 when Pitt was hired to teach a class in feature writing in the English department and to manage the student newspaper, The Parthenon.

Characteristically he did what was expected – and more. He created so much enthusiasm for his subject that College President Morris P. Shawkey challenged him to organize a journalism department.

The following year he did just that. He also organized the United High School Press, an annual convention, designed to encourage high school students to study newspaper work.A three day workshop-meeting of high school newspaper editors and writers, it drew young tourists to Huntington when tourism as a business was scarcely known. Offshoots of the UHSP were formation of a high school teachers association and a high school yearbook association.

All three associations drew more and more people to Huntington: High school editors and teachers came to learn. Many returned as college students. Meanwhile, they became part of Huntington business as a result of Pitt’s organizational ability.

With only 3 percent vision in one eye and blind in the other, he accomplished many things.

“If you can’t do a thing, teach it,” Pitt frequently quoted. But do it he did. Before he organized Marshall’s journalism department (in 1927) and before he became a professor, he worked as a reporter for the Clarksburg Exponent and Telegram, and the Shinnston News (1919). He was publicity director for Muskingun College. In later years he was consultant/representative for Advertising Inc. of Charleston in the 1950s.

He was a prolific writer, doing fiction for the old “pulp” magazines and highly specialized article for the “slicks.” Through the years he supplemented his teaching income by answering the call to use his energy “only for what he liked to do.”

To familiarize students with working aspects of the newspaper craft, Pitt brought in newspaper reporters and editors as guest lecturers. Later some of them were employed as members of the faculty including the late H.R. Pin chard, who taught history of American journalism, editorial and book review writing James Clendenin taught copy editing. Both were executives at the Huntington Publishing Co.

Col.J.H. Long, owner and publisher, who supported the journalism department, helped make its projects achieve their goal.

Later, courses in radio and television were added to expand the opportunities for students.

Public relations training was far in the future. The department was barely three years old when the Great Depression crashed on the country, leaving millions of people jobless.

And a lesser man than W. Page Pitt could have been left jobless. With printed and spoken word, he emphasized the need for training in other areas of the field. Pitt rode out the changing conditions of the times.

Women had never been encouraged to major in journalism. In tho e preWomen’s Movement days the prejudice against women for newspaper positions was strengthened by the economic recession.

On the majority of newspapers, women were hired only to write society news. It seemed during the Depression, nobody gave up any job, and there were no new ones. Pitt encouraged women to major in journalism.

During World War II when young men were called to the military service more than to college, a “petticoat staff ‘ put out The Parthenon. That situation was reflected nationally and eventually women were given more opportunities not only on newspapers but in all phases of journalism.

One such woman was Virginia Daniel, who worked in advertising for newspapers, including The Herald-Advertiser, where she polished her skills writing copy for advertising and a column on cooking and gardening. Later she became Mrs. Page Pitt and used her knowledge of him to write a magazine article, “My Most Unforgettable Character.” It was published in the August 1967 issue of Reader’s Digest.

In 1971 Pitt retired after being officially proclaimed by the West Virginia Senate “Grand Old Man of Journalism.” His 44 years of continuous service was rewarded, he said, in 1980 when the department became a school. It was officially dedicated in his honor as the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism.

In September of 1980, Pitt died in Stuart, Fla., after a long illness. But the man with 3 percent sight had lived to see his department burst at the seams as it expanded in number of students, class topics and vocations – because of his ideas and the energy to carry them out.

Probably the most visible testimony of the great changes is in a comparison of the university newspaper.Under him it grew to a self-supporting weekly focusing mainly on campus stories. Later it was issued semi-weekly, adding state, regional and national news but always with the focus on Marshall.

From a department that once prepared students only for newspaper work to a school where most of its students major in public relations/advertising, the W. Page Pitt School of journalism now is headed by the first chairman/ director who is not a newspaper man. Before he became a teacher, Dr. Harold Shaver studied and worked in public relations. For the future, the director sees no major changes.

Students are offered a wide choice of media, and all phases of journalism prepare them for the best methods of research to assist them in carrying out that choice.

“We will follow the trend for a course of info-gathering that covers the best way to get and process information from library research to government documents to data processing,” Shaver said. “Our great need is technology.”