By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 16 | AUTUMN 1993

Twenty-three years have passed and the memories of the tragic Marshall University plane crash continue to resurface. And, it seems, always in mid-November. Even if only for a moment. Here are a few of mine …

It was Saturday, Nov. 21, 1970, in Huntington. The embers of the tragedy continued to linger over the grieving city like a shroud.

A week had passed and still there was pain. Everywhere. Little pieces of it. Reflected

in faces. In voices. In the way we walked or talked or worked. Laughter had taken a leave of absence. Gaiety had become almost blasphemous.

Over on 18th Street the Gullickson Hall gym, which had been pressed into service for the families and relatives of the 75 who’d perished, no longer overflowed with mourners. They’d all returned to their homes. Heavy hearted. Many still imprisoned in the terrible shock of it all.

At 1:30, normally kickoff time on autumn Saturdays, the aching void was graphically accentuated because no football hung in the sky over Fairfield Stadium, with no rolling drums and no roaring crowd to accompany its flight deep into the receiving team’s territory.

There were no players on the field, no officials, no chain gang, no coaches, managers or cops – only 28 people dressed in dark clothes were on the field, laying wreaths alongside one another at the 50 yard line. They had come in a motorcade from the Marshall campus, headlights on and in single file through silent streets to pay their respects to a memory.

“Oh Lord of all of us,” the Catholic priest said. “You know how human we are and thus You understand why we must be here today.”

Two hundred people sat huddled together in a lower middle section of the west stands. They carried no pennants, no blankets, no thermos jugs, no booze. Opposite them, the student section in the east stands stared back blankly.No cheerleaders pranced before them. No band played Marshall fight songs. Only two youngsters sat on the concrete barrier below.

“We know there will be no game today,” the priest continued. “The game has been called off by Your summons of our friends to Yourself. But we are human and selfish and cry over their absence.”

I glanced over my shoulder at the stadium press box above. It was deserted, its stillness unbroken by clattering typewriters or the voices of statisticians calling out the plays.

“So we have come to their home field,” Father Robert Scott said, “and to show our affection for them lay a wreath in the middle of this beautiful Astroturf of which they were so proud.”

The lush green carpet glistened under the November sun. Overhead a small plane droned slowly eastward. A dog barked somewhere on nearby Columbia Avenue.

“Perhaps as we stand together on this turf where they gave their all for us we may feel close to them, our brothers,” Father Scott continued. “No one of us will ever enter this stadium and no Marshall game will ever be played here without thoughts of them.”

Beneath the stands the concession counters were closed. The entrance gates were padlocked. No ticket takers guarded the ramps. The scoreboard stood mute. No electric messages flashed information about first downs, yard lines, time outs, the quarters and the score. Neither was there a public address announcer keeping cadence with the ebb and flow of action on the field below.

To the right of the scoreboard, an American flag flapped gently at half mast and, as Scott spoke and the people listened, the wind would die and the flag would wrap itself around the slender pole as if in prayer.

“Oh Lord,” Scott petitioned, “grant them eternal peace and rest which enables them at this very hour to look upon us here and be with us. This is our faith! This is our hope! Amen.” He folded the piece of paper on which his prayer had been typed and stuck it in his pocket. Then the 28 people turned left and walked slowly down the north side of the field towards the new field entrance ramps. The 200 people in the stands and the two boys on the concrete barrier in the east stands watched them leave.

As the group shuffled up the concrete ramp their heels made muffled grinding sounds quite like football cleats; and, for a blessed instant, one expected to see the brave band of green and white clad players, all two score and five of them, making their way to their new dressing quarters behind the scoreboard.

When the group of 2 8 reached the dressing rooms, the people in the stands continued to sit and stare at the empty field. Again a dog barked on Columbia Avenue. The sound seemed to rouse them and they slowly began to file out of the stands. Some visited the wreaths at midfield. Others touched the Astroturf. Some did both.

It was 1:35 p.m. The memorial services in Fairfield Stadium for Marshall’s martyred football team had ended and its rise from the ashes scattered around that Wayne county hillside was about to begin.

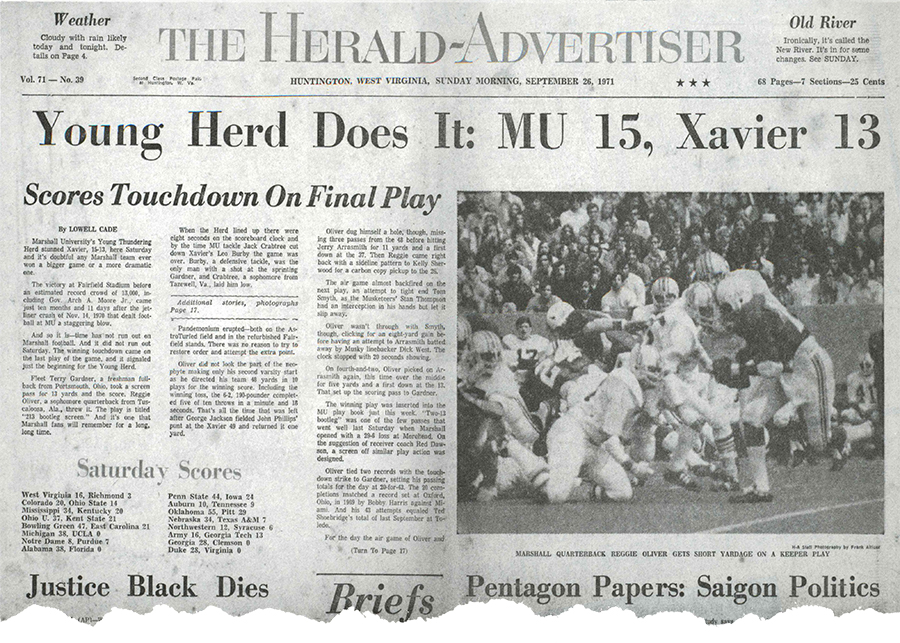

Ten months later – 308 days to be exact- that rise was given an incredibly dramatic boost, propelled, I remain convinced, by the supreme intelligence that created us all. Surely the ironies were too great, the coincidences too neat for it to be otherwise. Common, ordinary logic wouldn’t have dared to conceive a last-second victory in the first post-crash home game by these heirs to Marshall’s decimated program – the sentimentally baptized Young Herd.

That was the stuff of cheap Hollywood plot boilers. Only was it? Not this time. Not on September 24, 1971, a date too often forgotten as the anniversary of Marshall’s greatest football victory. A victory surely greater, and m.ore significant from an historical perspective, than the winning of the NCAA Division 1-AA national championship on Dec. 19, 1992 would be. Include here the hauntingly similar last play endings that marked the two games.

So let’s return now to that incredible day … a day that saw the Young Herd’s quarterback, Reggie Oliver, lacerating Xavier University’s defenses with a play called 213 Bootlega passing scheme that gave him a choice of three potential receivers.

With the game’s last eight seconds showing on the scoreboard clock and Xavier leading, 13 to 9, a miracle was needed for the Young Herd to achieve what everyone in the universe thought impossible – to win its first at home game since the terrible tragedy of the preceding November.

Down from the spotter’s booth Red Dawson’s Georgia drawl crackled over the field phone: “Let’s give ’em the 213 Bootleg Screen!”

Jim McNally, now the offensive line coach of the Cincinnati Bengals, was listening on the sideline phones and he passed the play to Jack Lengyel. The head coach quickly sensed what it might do – deceive the Musketeers into pursuing a familiar flow they’d been able to stop all day. Lengyel nodded and gave the play to Oliver who trotted back to the scrimmage line on the Xavier 13. At the snap the sophomore from Tuscaloosa, Ala., faked a handoff to halfback Randy Kerr running a dive into the weakside line, then Reggie bootlegged the ball back to the strong side where he pivoted and looked downfield for his three receivers just as he had repeatedly done before.

What Reggie saw was a delight. All three-tight end Tom Smyth, wide receiver Lanny Steed and flankerback Jerry Arrasmith were taking their defenders to the right side of the field while on the left side Jack Crabtree, his sophomore tackle, was bearing down on Leo Burby, the one remaining upright Muskie over there.

Quickly Reggie retreated, pivoted and fired a strike to Terry Gardner setting up to his left. Gardner had just blocked and then released Xavier’s defensive end to the outside. Now perfectly positioned, Terry looked the ball into his chest and took off at top speed on a southeastern angle down the left side, just as Crabtree was flattening Burby with a bone crunching block.

When Burby went down, the Fairfield Stadium crowd-13,500 strong, plus another 75 watching from up there somewhere – exploded into a stupendous roar, for now no Muskie was left standing to prevent Gardner from keeping his date with destiny. The Portsmouth freshman sprinted into the end zone untouched to set off one of the greatest victory celebrations in sports history. Certainly the most spiritually meaningful, anywhere, as Marshall players, coaches and spectators alike poured onto the field.

Leading the charge was Russell Lee of all people. He was one of Marshall’s greatest basketball heroes but here he was on this day of days running onto a football field and throwing himself, literally, into a mass of squirming Herd footballers in the south end zone where Gardner had completed his winning dash. Thousands more stayed near their seats too numbed, apparently, by the implications of what they’d just witnessed to leave.

Hundreds wouldn’t leave for hours. Many wept. Even then-governor Arch Moore -who had been at the scene of the plane crash within an hour after it had occurred-fought back tears in the press box where the normally cynical writers fought to keep their own emotions in check. The officials, meanwhile, noting the rapidly developing stampede, wisely waived the extra point try and fled with the stunned Xavier players. The extra point was unneeded anyway. Time had run out and the final score read, 15-13. It would remain there for a week.

The key to the game winning play was, of course, Terry Gardner. He had to execute his block and release on Xavier’s defensive end perfectly. There was no margin for error because in the straight Bootleg 213, he didn’t release as the pass would go to one of the three receivers going down field – Smyth running straight downfield, Arrasmith hooking back, or Steed slanting across from the left side.

Steed was another who had an important role. As the game’s last play began, this 175-pound freshman from Montgomery had already caught eight passes for 113 yards, more than anyone else on the field. Thus, Marshall strategists felt the Muskies would be keying on him. To make it work further, Steed would have to act like a primary receiver – which he did streaking along his route with two defenders in pursuit.

“We figured they’d key on Lanny Steed all right,” said Lengyel, the head coach and chief architect of this most improbable victory. “Lanny’s a great receiver and he faked their whole defense right out of the park.”

Gardner, flushed with excitement, was beside himself.

“I said to myself, ‘I’ve just got to catch this one. I’ve just got to. Then when I did and I saw Crabtree’s block, I knew I was in.”

“Go for broke, man!” Go for broke!” Reggie Oliver shouted.

“Yeah! Go for broke!” A dozen others shouted.

All this happened many, many years ago when you and I were younger, Maggie.Yet, when Willy Merrick kicked his game-winning field goal last year to bring the NCAA 1-AA championship to Marshall there seemed, somehow, to those of us who saw both, to be a mystical connection between the two – Bootleg Screen 213 in 1971 and Willy’s kick 21 years and two months later.