Remembering when Huntington was home to the squared circles

By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 17 | SPRING 1994

Traditions die slowly. About the time Calvin Coolidge declined to run and Henry Ford was building affordable motor cars, Huntington was a boxing and wrestling paradise. The energetic young city teemed with fighters, grapplers, promoters and managers plus the usual assortment of gimp-eared grifters drawn to these sweet ‘n sour sciences as moths are to light. Spiritually, it may surprise the under-40 set, reminders of our old burg’s love affair with the squared circles are with us still. Everywhere. In a vacant lot that once housed a makeshift arena, maybe, or a dry goods store transformed from a theater. Perhaps in the entrails of a low-slung, oblong block squatting on Third Avenue right where a training gym once thrived in a loft over a hardware store, or in a weed-choked railroad repair yard close to the pizza house and hot-dog landmarks of today.

Once a year the ghosts return during Golden Gloves week but, alas, they’re slowly disappearing too, if you get the point. Fortunately many of these wispy links to Huntington’s spirited boxing history were preserved by the late Mickey Davies, the Pittsburgh-born, Huntington-raised, Los Angeles promoter in a letter he sent me shortly before he died in 29 Palms, California, nearly a decade ago. Aboard Mickey’s facile pen, we can journey through that colorful bygone Huntington era. We can visit sites where old arenas and training gyms once stood, where punch and counterpunch, knock downs and double hooks aroused the seething masses. The big one, of course, was the old Vanity Fair area in the 600 block of Fourth Avenue. But when it was renamed Radio Center as the Huntington studios of radio station WCMI, Sir Richard (The Lion Hearted) Deutsch, otherwise known as Dick, was the big barn’s promoter and factotum in residence.

One block east and two blocks south of Vanity Fair, Joe Stender operated his pitch at Second Avenue and Eighth Street. Today the site forms the north wall of the Huntington Civic Center facing Veterans Memorial Boulevard. Few could claim more colorful neighbors in Stender’s era. A row of well-patronized “houses,” their red lights blinking at nightfall, nestled west of Joe’s entrance on Seventh Street.

The old Huntington Opera House was also in the neighborhood, at Third Avenue and Eighth Street. The Bazaar, a home furnishings store, is there today but when the coloraturas and basso profundi departed, the fight crowd moved in, pitching the ring on the first floor near today’s mezzanine staircase that leads to what once was the balcony. In between these eras the building became a vaudeville theater, then a movie house.

One outdoor fight site was located at 24th Street and 5th Avenue, and another on the outskirts of Guyandotte facing the Ohio River. Davies recalls “Johnny Roberts and Jimmy Perdue packing them in there to the tune of 14,000 bux.” Inco Park was still another site, along with League Park at Virginia Avenue and Seventh Street West and Clyffeside Park on the Kentucky side of the Big Sandy River near Catlettsburg. In fact there were almost as many fight joints as there were managers and promoters in this rambunctious period of Our Town’s past.

I didn’t know Stender or his contemporaries. Guys like Judge Newman, Shot Johnson, Pud Perdue and Billy Adams were before my time. Deutsch, however, was a friend of mine. So let’s start with Sir Richard, shortly after he counted the house receipts after one of his Saturday night wrestling shows. I remember he said to me, “Give me wrestlers anytime. They’ll all settle for hamburgers. Fighters? Even the bums want steak!”

This was a rare piece of social commentary on the continued popular appeal of professional wrestling and fe w promoters in the co un try were better qualified to discuss it than Deutsch, still without a doubt the most unforgettable character I’ve ever met in the sports world. A dapper little gent he favored bo w ties, bit cigars and Cadillacs in his 25 years as Huntington ‘s premier sports entrepreneur . That’s a fancy term he would’ve understood with the same street instincts he used to frame his hamburger and steak equation which, even at today’s prices, makes sense.

A heart attack killed Dick Deutsch in January of 1964. They found hi m face down in the bathroom of his tiny suite in the old Governor Cabell Hotel, arms outstretched, his nitroglycerine tablets just above him on the sink. Sadly we still haven ‘t seen the likes of him around he re since. He was among the last of a breed of promoters who lived by their wits, not out of briefcases.

I recall, for example, an otherwise quiet Saturday night. At about 10:30, I was in The Herald-Dispatch news room when Dick phoned me from his itty bitty office in Radio Center. So help me, it was no bigger than a broom closet which, in fact, it originally had been. He sounded desperate.

“Ern-nee !” he hissed, ” I’m hidin’.”

Naturally, I inquired as to where and from whom.

“The nuts,” he whispered . “They’re poundin’ on the door . They’re tryin’ to break the [bleep] thing down to see if l’m inside . If I am, which I am, they’ll kill me!”

I suggested he cal l the police.

“If I do that, then the next time they’ ll know I’m in here, ” he said.

“Then how in the hell can I help?” I shouted.

“Just stay on the phone, ” he said . “If the [ bleepers] do kill me I want you to be witness.”

Fortunately, Dick’s door, which re ally looked like a broom closet, held fast under the assault. Later, in the welcome safety of an after- hours den of iniquity that shall remain nameless here, Dick told me what had happened. It seems the Golden Greek, a bad guy, and the Great Scot, a good guy, had somehow misread their rehearsed grand finale signals and the Greek had prevailed in a dastardly way. Then all hell broke loose. Roughly half the downstairs portion of the enraged crowd of 2,000 wild-eyed fans had chased The Greek into his dressing room, where he hid behind a scalding hot shower. The other half had gone looking for Deutsch. Fortunately, there were no injuries.

Sometimes people do get hurt when fans get unruly. Usually, it’s the wrestle r. The Sheik was such a victim one scary night at Veterans Memorial Field House. Deutsch had set up operations there after Channel 13 moved into Radio Center, forcing him to look for new quarters.

Paired in the star match were two bad guys, Dick the Bruiser, a former Green Bay Packer, and the Sheik. A most unusual arrangement . Bad guys as wrestling “opponents ” don’t mix well.

The chemistry is out of whack. Every wrestling ac t need s a hero and a villain. Who do you root for if you’ve got two villains going at each other? Anyway, near the end of the match the Bruise and the Sheik went into their foot race. Around and around the ring they went, the Bruiser burr -headed and snarling, chasing the Sheik, babbling incoherently, his Arab headgear askew, eyes widened in “fear.” (Note : In a straight match h e’d hav e leveled the Bruise r in seconds.)

Suddenly, the Sheik leaped through the ropes and onto the floor , as according to the script. Too late, he realized, a cordon of cops assigned to protect him on his exit, were stationed on the other side of the ring. In the ring, the Bruiser saw the Sheik’ s problem so he started out after him to create a diversion. But by then the Sheik was sprinting past the ringside customers, still babbling, heading for his confused protectors. He never made it. A “nut” in the crowd smashed the Sheik in the midsection with a folded metal chair. The Sheik screamed horribly. Doubled over in pain, he staggered into his dressing room and collapsed. Four ribs were broken. Two others cracked. The chair-wielding fan was quickly apprehended, but the Sheik declined to press charges. To do so, he would have been required to reveal his true identity and his prosperous middle class, American-born upbringing in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Although theatrical, Texas-style “exhibition” wrestling has been around for at least 75 years, the current versions bear little resemblance to the product Dick Deutsch sold in Huntington. TV packaging has changed it into a theater of-the-absurd. The “actors” involved don’t even pretend to wrestle anymore. They’re really just pumped-up tumblers with minimal catch as catch can skills. But if Dick were still alive, he no doubt would have adjusted to the change. No stranger to absurdities, he was the guy who kept all the water fountains in Radio Center turned off and made sure that water was also unavailable at his concession stands.

“If anyone gets thirsty in here, it’ll cost ’em,” Dick correctly reasoned.

Joe Stender, I’ve been told, was no less practical at protecting himself against unexpected eventualities. Stender not only promoted fights, he managed fighters. He owned the gym where they trained to fight, the arenas in which they fought, and the restaurant where they ate. And for good measure he owned a horse room over his popular Monarch Cafe, with a floor-to-ceiling tote board that posted up-to-the-minute odds and prices from tracks all over the country. Card tables and slot machines occupied the rest of the room. Needless to say, the joint was usually jammed. How the cops missed all the foot traffic it attracted I’ll leave to you to decide.

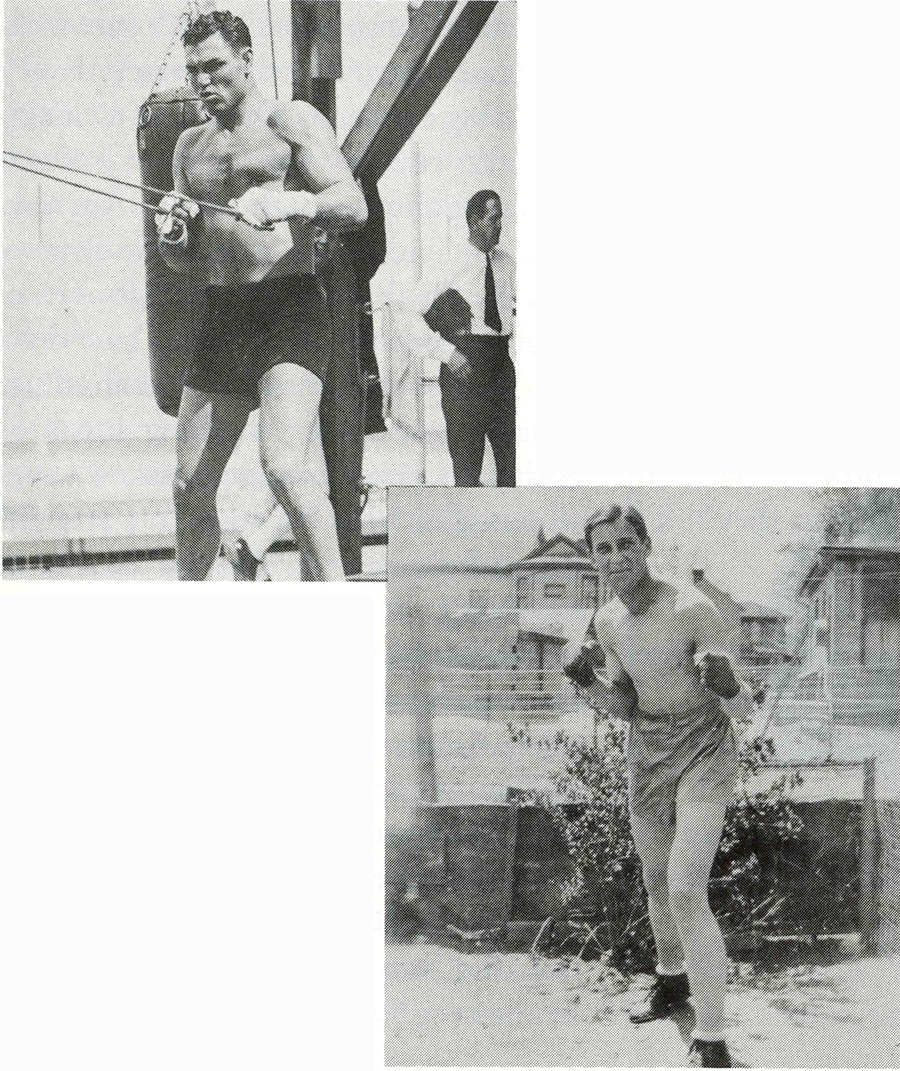

Stender’s greatest money coup -among the many he racked up as a boxing promoter – occurred on March 18, 1932, when he signed Jack Dempsey to fight a pair of two-round exhibitions against local heavyweights Jack Kearns and Billy Miles at the old Vanity Fair. It was quite a catch.

Dempsey, the aging former heavyweight champion, was nearing the end of what would be his last extended exhibition tour and he agreed to fit Huntington into it after he was to appear in Clarksburg. Jack had a soft spot in his heart for southern West Virginia, anyway. His parents had migrated to Colorado from Logan County, and he returned often to visit his many relatives.

Naturally, Dempsey’s signing was big news. He was still enormously popular.Nevertheless, Stender took out some tactical insurance to clinch a sellout. He put up a $500 bonus – big money in those Great Depression days – for either Kearns or Miles if they knocked Dempsey down, if not out. This implied that the exhibitions would be real fights. Kearns didn’t bite. Miles did. In a way. He was quoted as promising to show the aging Manassa Mauler “a thing or two,” but, according to legend, by the time Stender and Clarence Barber, Billy’s manager, put the word out they had Miles telling everyone he’d deck Dempsey and win the $500.

Billy Miles, born William Mileski, was a brave warrior. But by fight time, he admitted to me years later, he had a bad case of stage fright. He was by all accounts an above-average boxer with real power in either hand but he knew he was no Dempsey. Few fighters were.

So the brash statement attributed to him in the press and fed to Dempsey by

Stender himself was taken seriously by the public and Jack. That’s why he had the heebie jeebies. In later years Billy blamed his manager, Barber, for the predicament he was in, rather than holding Stender accountable for it.

But, give Billy Miles credit. He tried. Oh how he tried. Shortly after the bell sounded he managed to land a solid left hook on Dempsey’s jaw. Dempsey’s knees buckled. He fell into the ropes. The sellout crowd at Vanity Fair roared. But that, alas, was Billy’s last hurrah. Here, he made a 19 year old rookie fighter’s mistake. He stepped back instead of attacking. That was all the reprieve Dempsey needed. He shook off the punch and unleashed a furious barrage of punches, including one that caught Billy flush on the face. Down he went. It was all over. Billy Miles never fully recovered. He was plagued by headaches and a serious sinus condition for the rest of his life.

Then there was the night that, thanks to Stender, Dapper DickMcDonie won the lightweight championship of West Virginia while he was serving soft time in the county jail. It was 1932 and Billy Williams was to defend his title in the old National Guard Armory in Charleston and the place was quickly sold out. But on the day of the fight Billy’s opponent pulled out. Desperate, the promoter phoned Stender in Huntington and asked him if his lightweight, Lewis

(Kid) Cook was available. He wasn’t. He was hurt. Next the promoter asked if Dapper Dick McDonie, another Stender lightweight, was free. Well, he was and he wasn’t.

“He was in the cooler for a few days,” Mickey Davies recalled. “The promoter gets hysterical. To calm him down Joe promises to talk to the sheriff to see if he can get Dick off or at least out to take the fight. The sheriff is a fight fan. He lets Dick out on the promise that he’ll come right back after the fight and finish his five days.”

The end of the story continued to amaze Mickey Davies until the ends of his days. Dapper Dick McDonie, without a single minute of training, and atrophied by his enforced idleness, “beat the hell out of Billy Williams for the title,” in Mickey’s words.

Afterwards, true to his word, the new lightweight champion of West Virginia returned to his cell, Davies said.

Folks, they just don’t make ’em like that any more.